100 years later, Second Ward alums carry on legacy of Charlotte’s first Black high school

A century ago, two new high schools opened in Charlotte.

One was named Central High School, built in the Elizabeth neighborhood for white students in the area. The building still stands today, the structure now a part of Central Piedmont Community College.

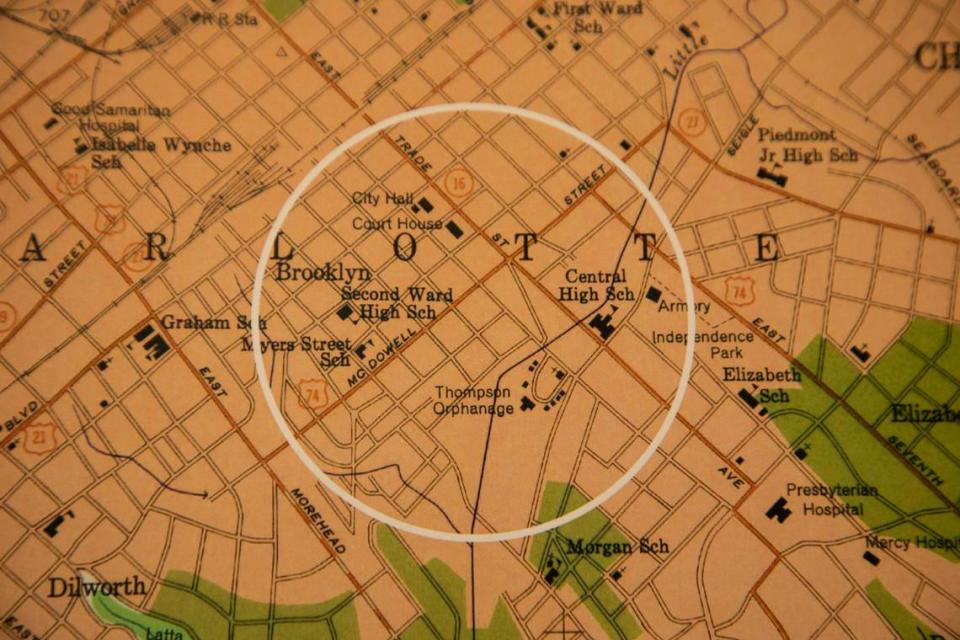

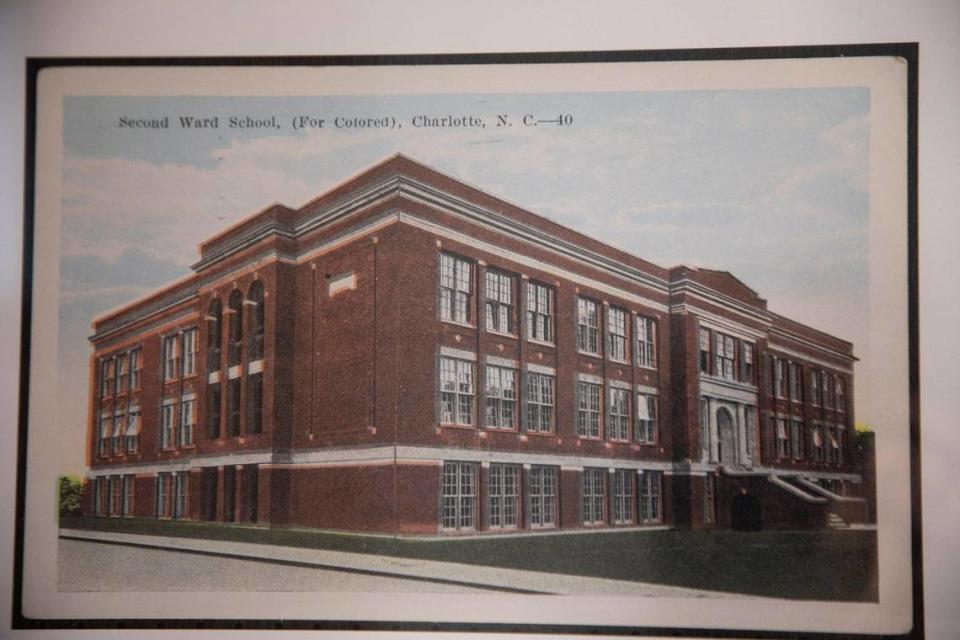

The other was known first as the Colored High School, and eventually Second Ward High School. Black students from throughout Mecklenburg County, but especially in the Brooklyn neighborhood where it stood, attended.

One white school. One Black school.

One building still existing, one gone.

By 1959, Central High students moved to form what is now Garinger High School.

By 1970, Second Ward High School had been razed after the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools board declared the structure was “a hazard.” Only the Second Ward gymnasium still stands on Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard, the building designated a historic landmark in 2008.

The epitaph for Second Ward High School says it existed from 1923-1969, closing ostensibly in the name of desegregation. But what’s missing in that shortened summary is the meaning the school held for Black students who attended and learned there, who made lifelong friends and memories.

And what’s also not detailed in that short version are the more complicated reasons why the school closed. Among them: unequal funding, the demolition of the Brooklyn neighborhood where the building stood in the name of “urban renewal” and hasty decisions made by the Charlotte-Mecklenburg school board after court-ordered integration.

But as the 100-year anniversary of the opening of Second Ward High School approaches in the fall, alums of the school are fighting to make sure the first-of-its-kind school in the area is never forgotten.

“It is my commitment to those folk who came before me to carry the legacy of their mission,” said Arthur Griffin, a Mecklenburg County Commissioner and a 1966 graduate of Second Ward. “Their mission was to keep the dreams and hopes and legacy of Second Ward High School alive, as well as the communities that fed into that high school starting in 1923.

“The torch was passed to me and I want to do something to keep that dream alive.”

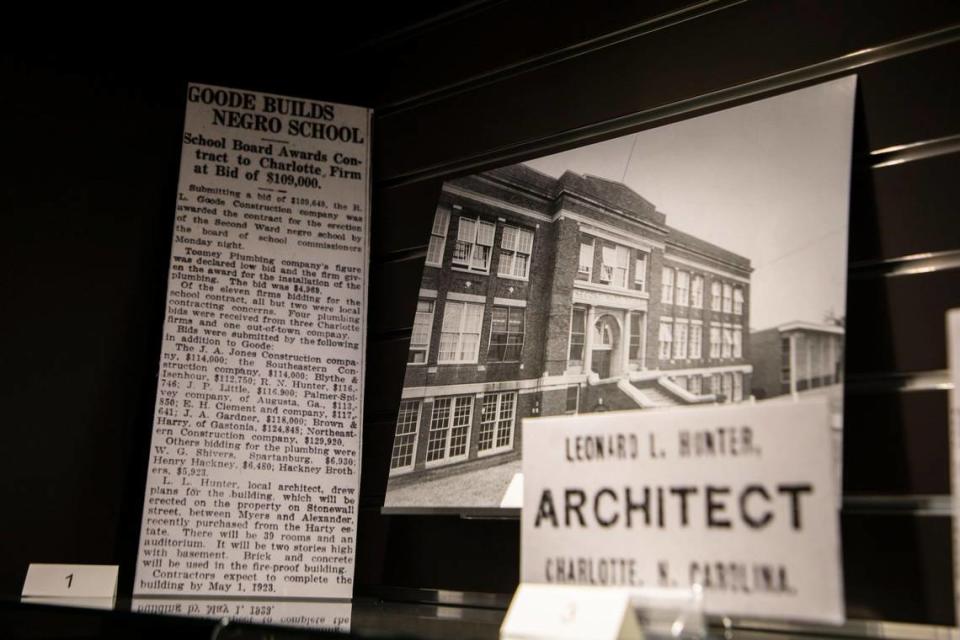

The opening

More than 100 years ago, the man who would become the first principal of Second Ward High School wrote a letter to the editor of The Charlotte Observer praising the planned opening of a new public high school in Brooklyn.

“One of the greatest blessings to come to us now — and it should be praised by every colored citizen within its bounds — is the fact that Charlotte is making provision to give every colored child who will take it a high school education with some industries to help him decide what he will do and be with his life,” wrote W.H. Stinson, then the principal of Myers Street School, on May 30, 1922.

Until then, if Black students in Charlotte wanted an education, they had limited options — typically, either a school outside the city, a private school or a church-run school. And obtaining an education was a newly valued commodity in the South in the early 20th century.

“Having a high school meant you had opportunity,” Charlotte historian Tom Hanchett said. “Education was something that had been denied to African Americans by law in slavery times. And so when freedom came, the opportunity to go to a school was very important to people.”

Quickly, the school began attracting Black students from throughout Mecklenburg County. But because it was located in Brooklyn —then considered the center of Black life in the city — it was more meaningful.

“You can’t separate the two,” Griffin said. “That’s family. The school was a community. It was an oasis for that community.”

John Pettis, now 74, grew up three blocks away from Second Ward High School, and said he couldn’t wait to go to the school when he was younger. His older siblings went there, his neighbors taught there. He could walk past the barbershop and the grocery store on his way to classes.

“We had everything in that community that we needed,” said Pettis, who graduated in 1967. “It was like a city within a city.”

“What people say we need now, we had then,” said W. L. “Pop” Woodard, a 1967 graduate of Second Ward. “Brooklyn made Second Ward (High School).”

The memories

It didn’t take long for Second Ward to become a beacon for the community.

Prominent African Americans who once spoke at the school include George Washington Carver and Jackie Robinson. Students could take classes to learn everything from practical home economic and auto repair skills to Latin and more traditional subjects of English and history.

Spencer Singleton grew up nearby, but decided to go to Second Ward when he heard the school’s band play at a parade.

“And they were just fantastic. From that moment … it was like, ‘Hey, that’s where I’m going,’” he said.

Singleton, 72, met his closest friends at Second Ward before graduating in 1968. Some of them joined his jazz band, Sound Waves of Charlotte, where he still plays trumpet whenever possible.

Roosevelt Gray is 88 years old, now, and graduated in 1953, but still can rattle off the names of all his favorite teachers. Even now, he wears a slick suit whenever he’s out on the town and takes pride in always being on time — two traits he learned when he was a high school student at Second Ward, he says.

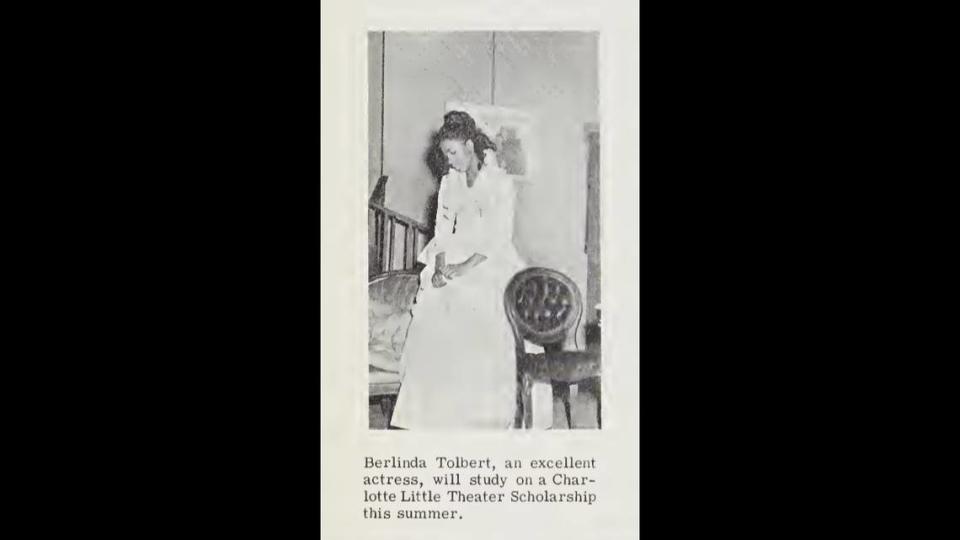

And Berlinda Tolbert, who would go on to play Jenny in the 1970s TV hit “The Jeffersons,” began her acting career at Second Ward High School in the mid-1960s.

“I always felt like I belonged. I was encouraged,” she said. “They (teachers) knew your name. … They wanted to be involved. They cared. Now, what is it that motivates someone to care? Perhaps that has to do with a love for children, a love for their occupation, and a desire to make a difference.”

Which is not to say everything at the school was blissful.

Robert Parks, who graduated in 1959, said he had to go to class in shifts because the school was overcrowded. Former students also remember that the school colors happened to include the same royal blue hue that Central High used — and athletic uniforms were hand-me-downs that had been discarded from Central.

Woodard said he never received a new textbook while he studied there; each one had been used for at least several years by white CMS students at other schools before being cast aside.

The closing

The reason the shuttering of Second Ward High school “still burns” Singleton is because it happened abruptly and reeked of betrayal.

In 1967, Charlotte voters passed a $35 million school bond, thanks in large part to the support of Black residents, who saw that $2 million of that money would be earmarked for a renovation of Second Ward High School.

Three separate times that year, the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools board formally endorsed a plan to keep Second Ward at its existing location, while modernizing the structure and shifting its focus to vocational studies. It would be renamed Metropolitan High School.

Still, by November 1967, school board vice chairman Harrison Belk raised the question of “whether the school should be built where no students will live when we complete the building.”

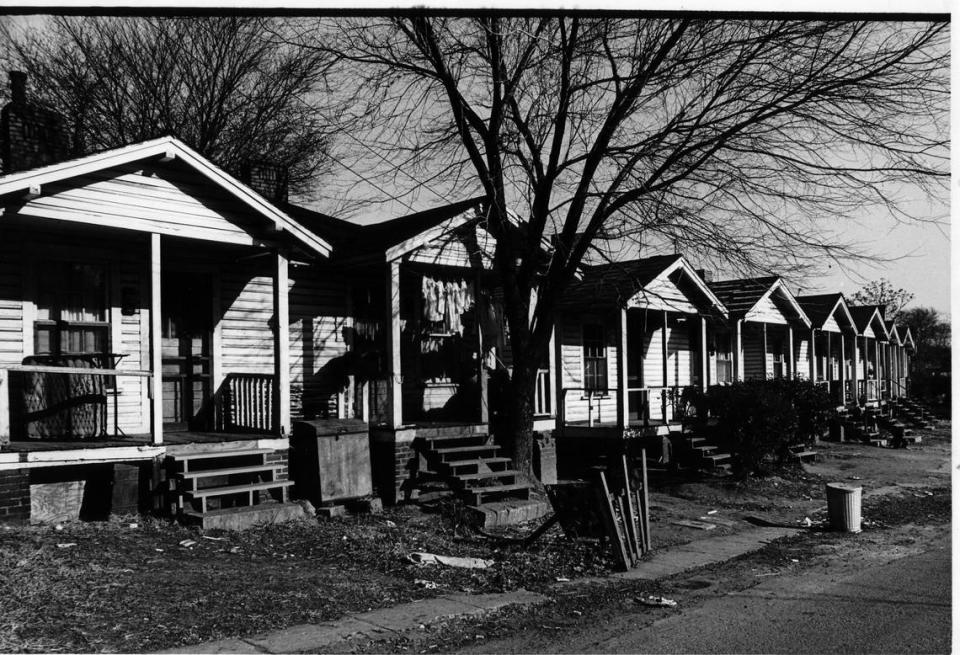

The area was being emptied, of course, because Brooklyn was in the process of being demolished in the 1960s and ‘70s under the guise of “urban renewal.” Stories in The Observer during the late 1950s and ‘60s described the area as blighted and called it one of Charlotte’s “slums.”

That wasn’t accurate, Hanchett, the historian, has said.

Yes, there were slums but there were also houses, businesses and restaurants, a library, hotel and theaters. Over 11 years, Charlotte tore down 1,480 structures in Brooklyn, including numerous Black churches.

“‘Urban renewal’ is one of the great tragedies of American history,” Hanchett said. “The school could have been preserved and expanded as an integrated school because it was right in the center of the community. The Charlotte powers-that-be chose not to, and it was a very sad time for people who loved that school.”

But the construction of Metropolitan High wasn’t officially halted until March 1969, when a federal judge ordered CMS to integrate schools. The CMS board chose to comply by shutting down seven all-Black schools and busing those students from the center of Charlotte to formerly majority white schools.

At the time, noted civil rights lawyer Julius Chambers said he was disturbed by the school board’s plan to bus 4,200 Black students to predominantly white schools, saying it was “simply a one-way busing proposal.”

“I can’t see any good in what they did,” Singleton said. “Because if promoting integration was what was happening, the key point was, hey, this is a central location and it will be easily accessible to all the communities surrounding here. So it was in a perfect place to integrate.

“It hurts,” Singleton continued. “I tell you, the whole thing of closing that school, it’s like it was yesterday when I talk about it. It doesn’t go away. It’s just … it was awful the way they did that. That was just … that was just awful.”

The legacy

These days, the graduates of Second Ward High School are dwindling. The last group to receive diplomas from the school did so 54 years ago, making the youngest among them in their early 70s.

Still, those with connections to the school gather whenever possible to reminisce. A Second Ward-West Charlotte breakfast club meets weekly, and men who were once fierce rivals on the athletic field now sip coffee together.

And potential plans for the construction of a new Second Ward High School at the site of the former school — included in the latest CMS nearly $3 billion bond proposal — are giving some renewed hope that a physical structure will exist again.

“I’m pessimistically optimistic about this, but I hope it happens,” Singleton said.

No matter what, the Second Ward High School National Alumni Foundation strives to keep the memory of the school alive, 100 years after the school first opened and gave education and hope to Black students in Charlotte.

“Those people who remained in Charlotte and kept Second Ward alive, I think they’re heroes,” Tolbert said. “And they’re to be applauded for doing that. Because Second Ward would be another lost memory — would just be in memory alone — because there is no building. There is no building, and yet, here it is 50 years later (after it closed), and we’re still celebrating it.”