101 Park Avenue's glass exterior wraps, reflects Oklahoma City's past

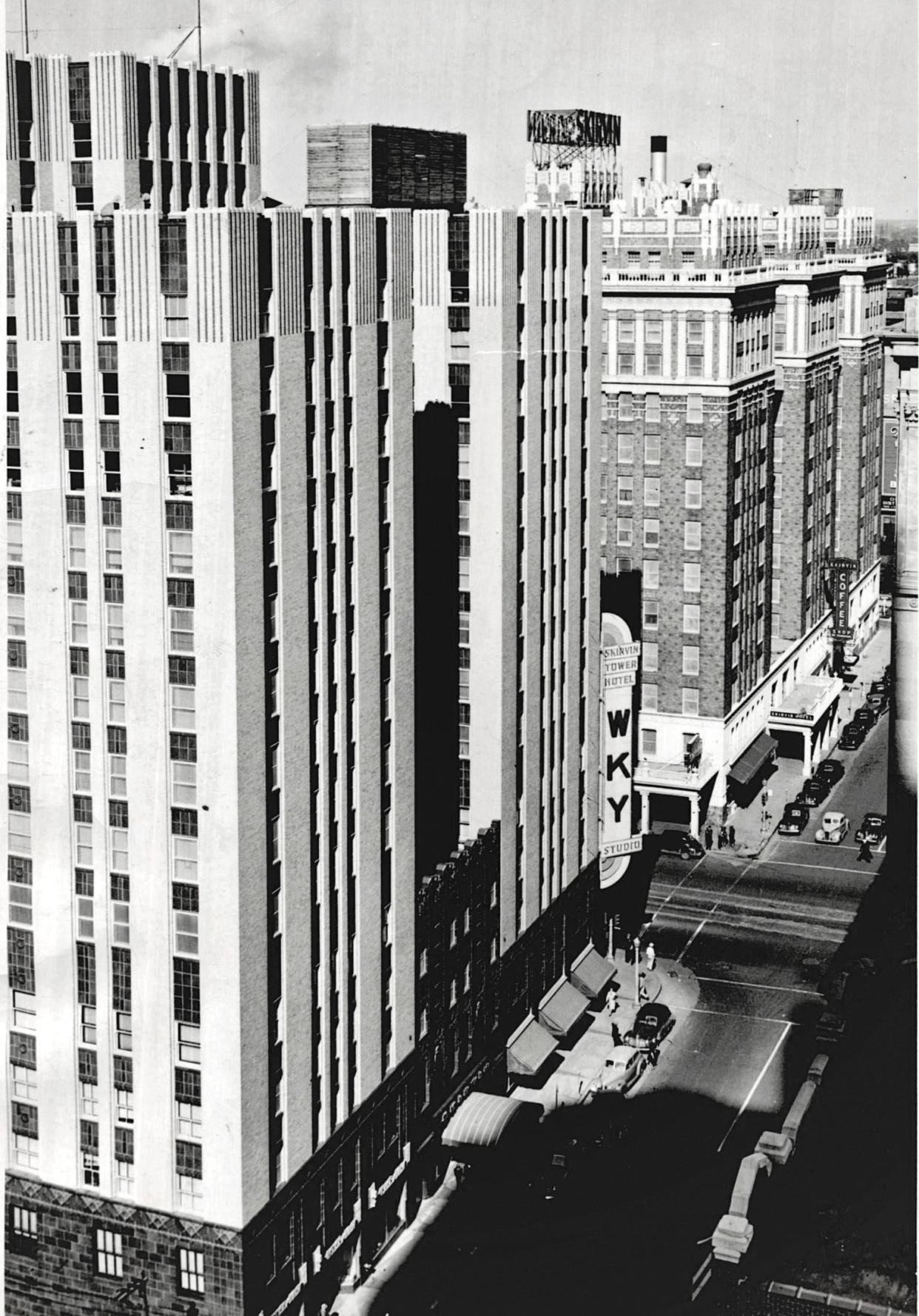

At just 14 stories, the 101 Park Avenue Building located on the northeast corner of Park Avenue and Broadway looks like a mid-1970s, midrise glass-covered building.

But its glass exterior ensconces a colorful past that forever links it to the Skirvin Hilton across the street and the Underground, a tunnel system that connects it with the hotel and numerous other downtown buildings.

It also is a source of memories, archived news articles and images involving hundreds (if not thousands) of events held inside the building between 1938 and 1971, where Oklahomans gathered to raise money, be entertained or to hear from generational influencers and politicians.

More: A fast ride between downtown OKC and Tinker eyed as part of Regional Transit Authority

When owner W.B. Skirvin started building the 101 Park Avenue Building in 1931, he named the project the Skirvin Tower, intending to further grow the namesake hotel he opened in 1911.

Skirvin already had expanded the hotel, making it one of the nicest in town.

But as the Biltmore Hotel, the First National and Ramsey Tower were being built two decades later, he sought to take his operation to another level.

Initially, Skirvin and architect Solomon Layton planned to build the tower to 26 stories, adding another 700 rooms to Skirvin's hotel operation and creating a first-class banquet hall and a top-of-the-building outdoor roof garden where guests could be entertained with live music.

He also built public-use and service tunnels under Broadway, increasing access between the two properties for the staffs serving the hotel and tower and the buildings' guests. Decades later, the public tunnel was incorporated into Oklahoma City's Concourse system, known today as the Underground.

The bottom five floors of the property were built in a rectangle base to support upper floors, built in a u-shaped pattern.

A lengthy court battle between Skirvin and his kids over ownership of his estate and the Great Depression, though, significantly slowed progress on the tower.

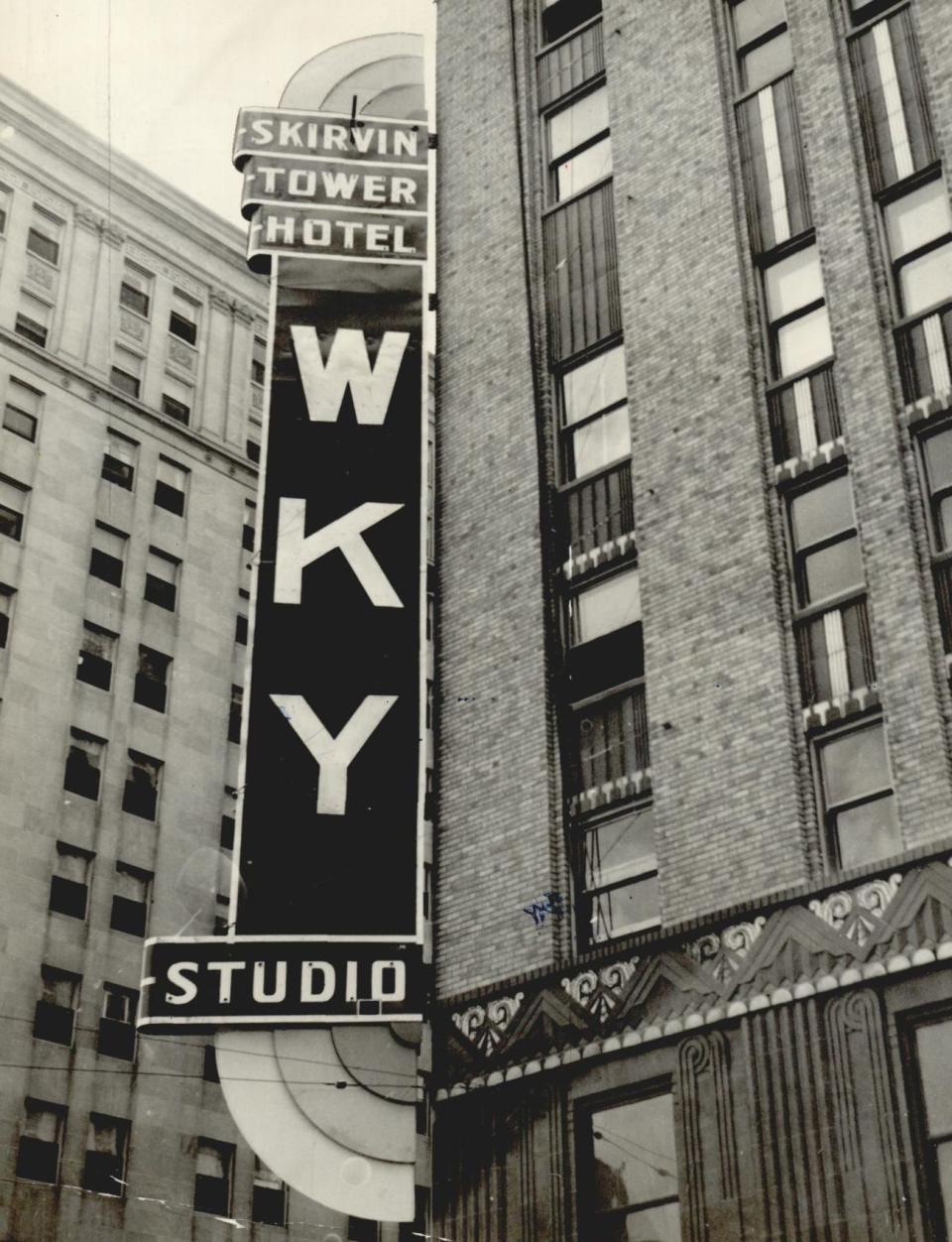

Ultimately, Skirvin was forced to cap the tower at 14 stories. While it didn't include the roof garden he had hoped for, it still included the banquet hall — the Silver Glade — on two of its lower floors and first-class studios for WKY Radio on another floor, including ones for a Kilgen organ and orchestral performances.

When Skirvin died in 1945, the tower's upper-floors remained mostly unfinished as his family sold the tower and hotel to Dan James for $3 million. James transformed the Silver Glade into the Persian Room by adding carpeting, mirrored columns, expensive drapes and updated furniture before inviting state dignitaries, Hollywood stars and locals to its grand opening in 1949.

James also built the swanky Tower Club in 101 Park Avenue's basement before deciding to sell it and the hotel across the street to an out-of-state ownership group in 1964.

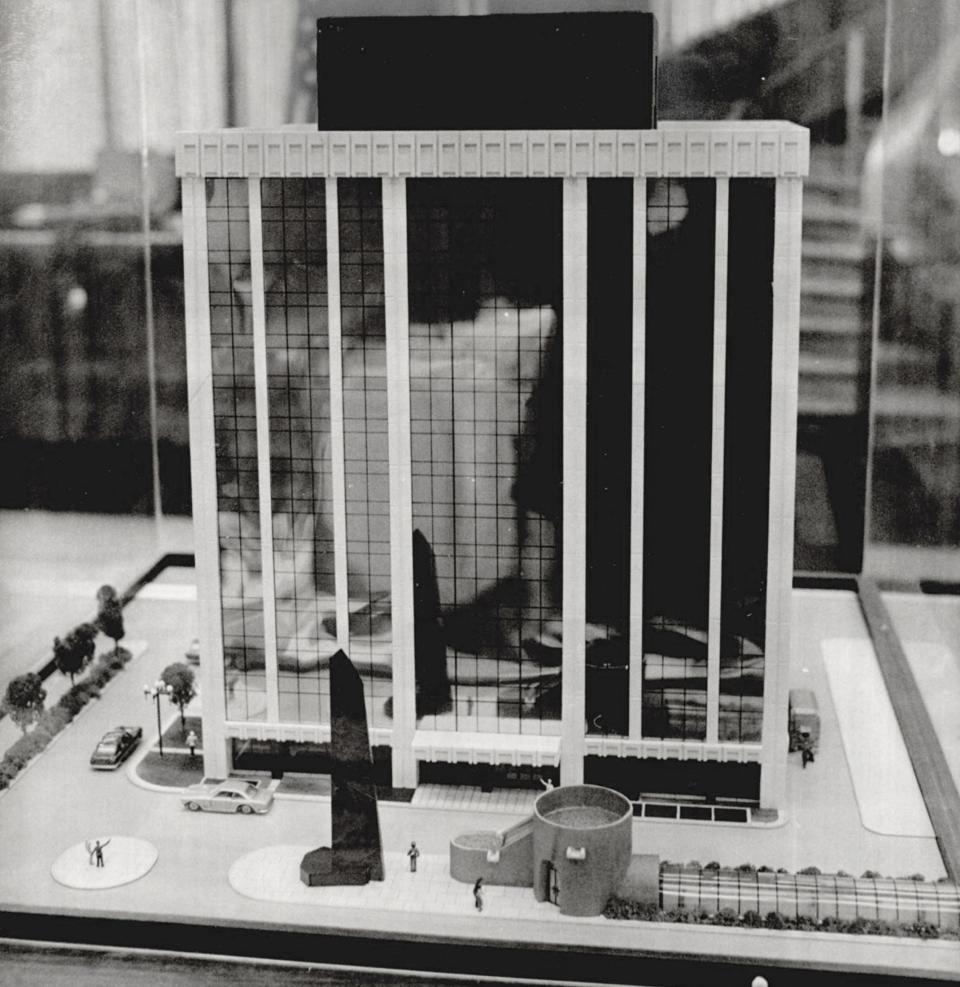

That group, which called itself the Syndicate, proposed taking the tower to a height of 32 stores, but sold it and the entire Skirvin hotel operation to a local named H.T. Griffin the following year.

More: Is downtown OKC ready for a brand-new apartment tower?

Griffin, who knew nothing about operating hotels, only agreed to purchase the operations so he could secure an outlying piece of property the hotel owned across the street that he needed to build his tower (known today as the BancFirst Building).

Griffin sold the Skirvin Tower after closing its Persian Room and Tower Club in 1971 to the Oklahoma City Federal Savings and Loan Association for an undisclosed amount, shortly before declaring the hotel operation bankrupt.

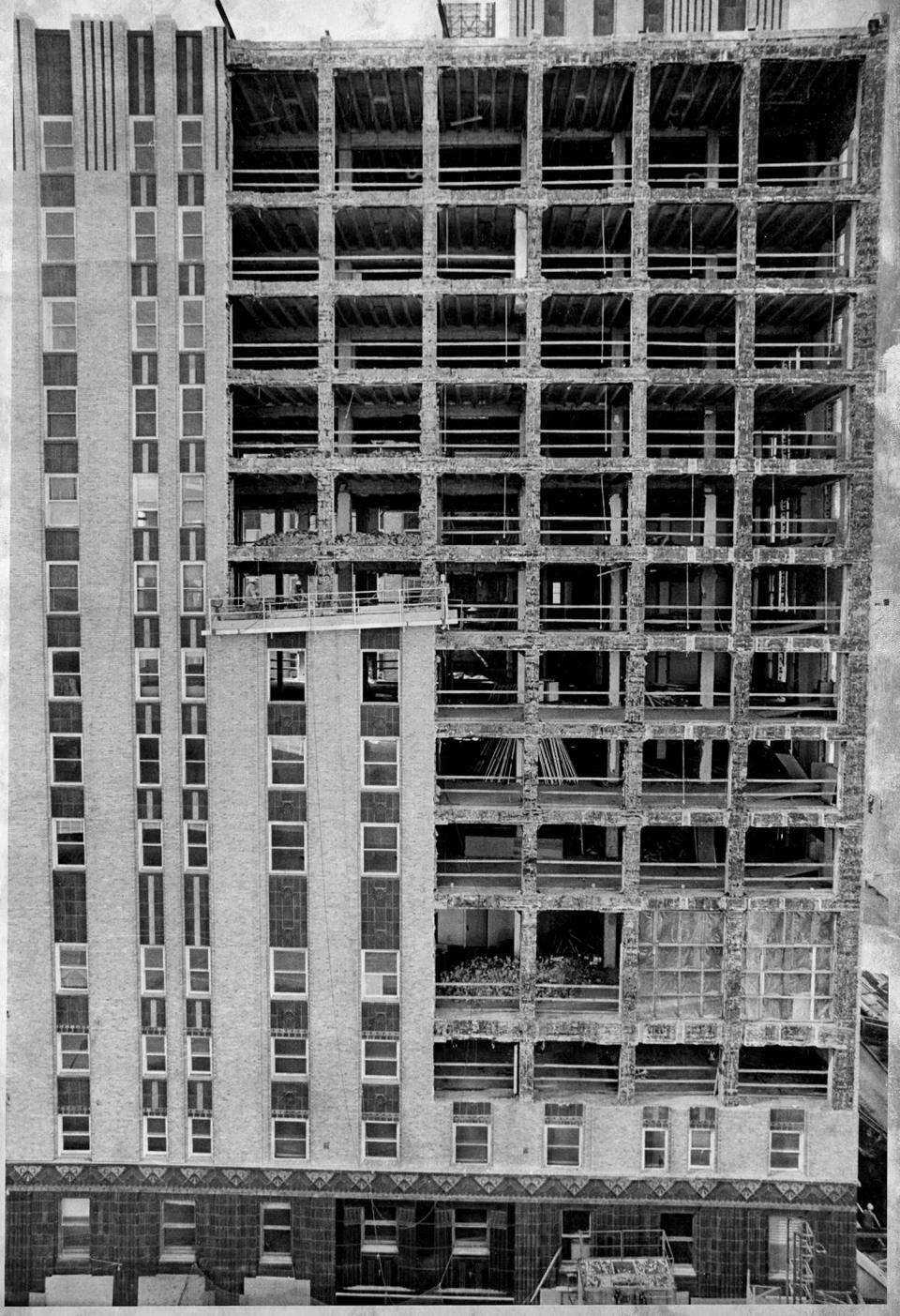

Oklahoma City Federal Savings and Loan overhauled the property during the next couple of years by removing its original exterior and by adding space to its upper floors to create a rectangle building with its current glass and concrete façade.

A decade later, the building changed hands as Jere Sturgis, a Penn Square Bank-backed oilman, acquired it from Continental Federal Savings and Loan and announced he would expand the tower to 28 stories, finishing what Skirvin couldn't a half-century earlier.

While Sturgis added four express elevator shafts to the existing building to support the planned expansion, his dream evaporated as the price of oil fell during the 1980s collapse of the energy industry.

The building's ownership remained in out-of-state hands until 1995 when Chuck Wiggin, a local real estate developer, made a deal with partners to acquire the tower. Later, Wiggin acquired sole ownership of the property.

Wiggin, whose company Wiggin Properties owns and operates numerous buildings within Oklahoma, overhauled the tower's lobby in 2006 with the help of sculptor Jesus Moroles as part of a plan to allow his ground-floor tenant, BC Clark Jewelers, to expand its showroom into spaces fronting Broadway and Park Avenue.

More: Cocktail enthusiasts can now check out The Library of Distilled Spirits at First National Center

The lobby project was complicated, as it required the opening up of lower levels of express elevator shafts Sturgis had added decades before.

Wiggin's staff also has been dealing with those shafts on upper floors, as well, removing them where possible to fit clients' office needs.

Wiggin said his motivation to acquire the 101 Park Avenue property was based on his desire to see it used for its highest and best purpose, a building capable of providing Class A space for large, medium and small businesses.

Its largest tenants since Wiggin became involved with the property have included an oil and gas company and Sonic before it moved into its headquarters on the Bricktown Canal.

Beyond the lobby, the building's high-end finishes include floor plans designed to appeal to large and small tenants and large windows that provide tenants with views of the State Capitol, the Skirvin Hilton, Kerr Park and Sandridge Commons.

But Wiggin also has helped preserve Oklahoma City's history by playing a role in helping a group get the financing it needed to acquire, renovate and reopen the original hotel.

More: West downtown development could skyrocket with relocation of Oklahoma County jail

101 Park Avenue now has a vacancy rate of about 50%. While COVID-19 impacted the office market citywide, Wiggin said he continues to see interest from clients who are seeking Class A office space.

"Your story is a reminder of how old buildings have a lot of stories held inside their skin that otherwise wouldn't come out," Wiggin said. "That's particularly true with 101 Park Avenue, because you wouldn't know from looking at it today that it had ever been built originally to operate as a hotel.

"Today, it looks like a 1970s-era headquarters office building that was built to a very high standard that an investor-owned building might have not been built to."

Business Writer Jack Money covers Oklahoma’s energy and agricultural beats for the newspaper and Oklahoman.com. Contact him at jmoney@oklahoman.com. Please support his work and that of other Oklahoman journalists by subscribing to The Oklahoman.

This article originally appeared on Oklahoman: Park Avenue landmark reflects, hides Oklahoma City history