102 years after the Tulsa Race Massacre, here's where efforts to reconcile and revitalize stand

More than 100 years after what some consider one of the worst incidents of racial violence in the country's history, Tulsa is making progress towards the revitalization of “Black Wall Street” and reckoning with the destruction of one of the most thriving communities in its heyday.

In the aftermath of 2020 protests surrounding the murder of George Floyd and the 100-year centennial of the Tulsa Race Massacre in 2021, heightened awareness led to more coverage on a foundational moment in U.S history that many knew little about.

In an effort to revitalize a once-thriving business district known as Black Wall Street, which was decimated in the massacre, the city of Tulsa has implemented a master plan that “ensures the social and economic benefits of redevelopment are experienced by Black Tulsans, by descendants of the Race Massacre, and by future generations and their heirs.”

Read about the history of Tulsa, the massacre and Black Wall Street.

When was the 1921 race massacre? What events led up to it?

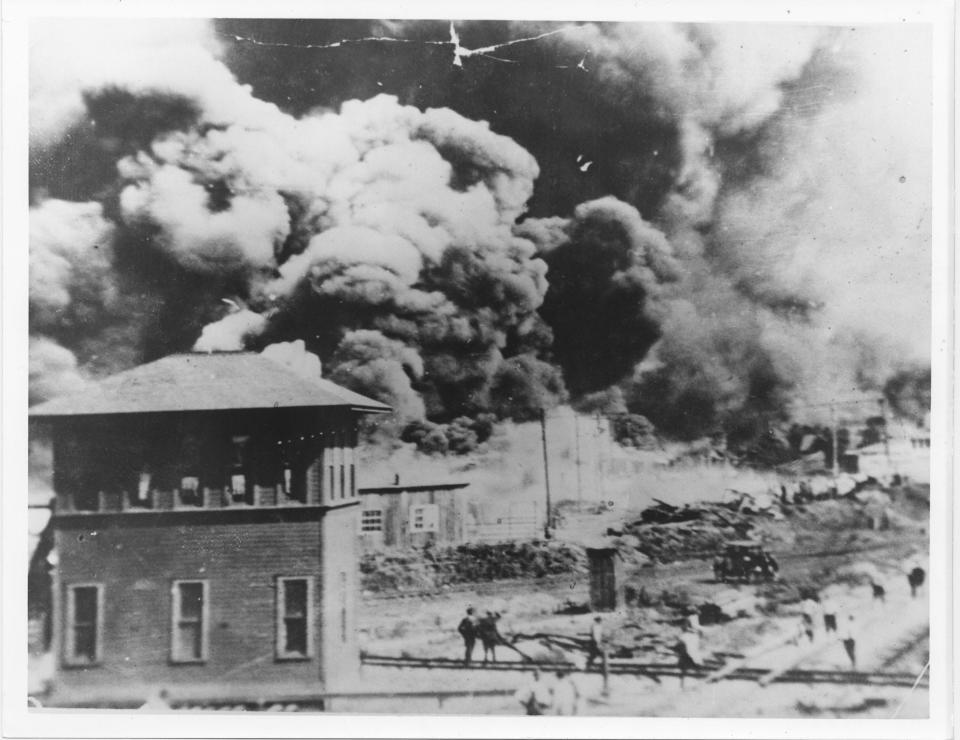

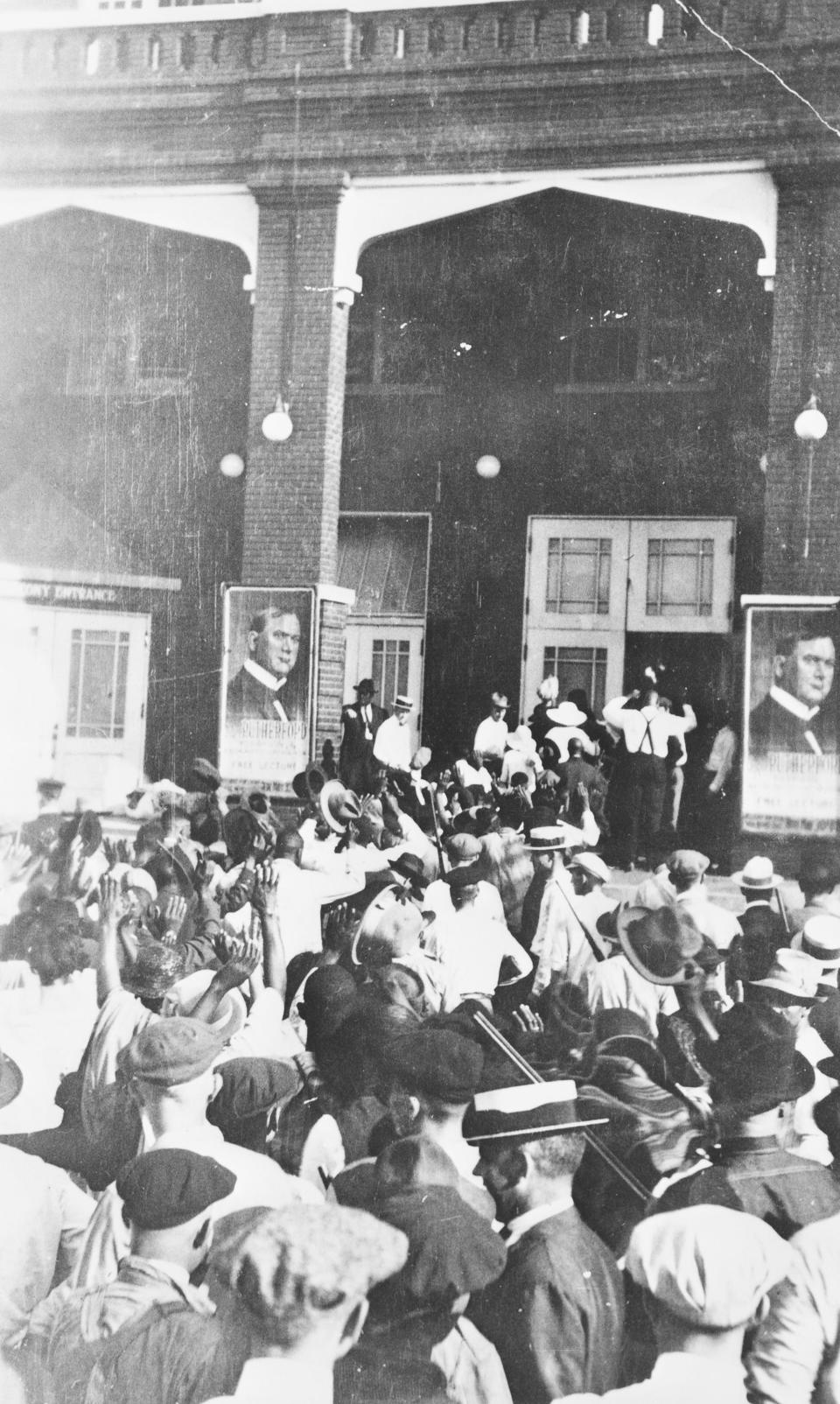

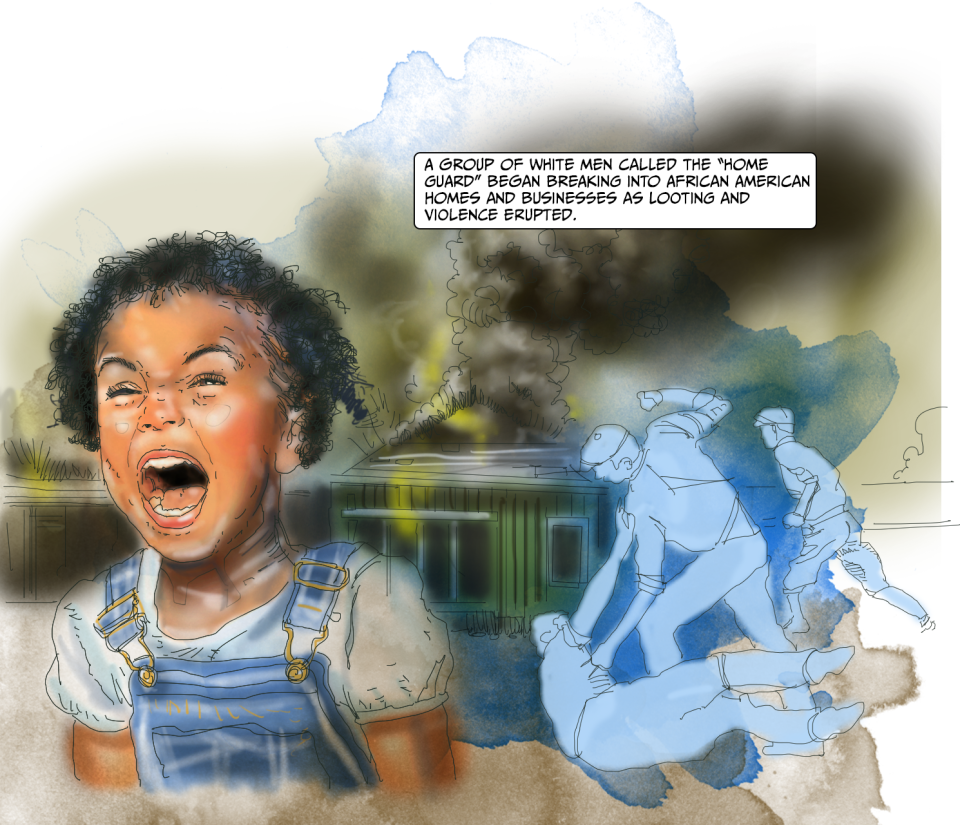

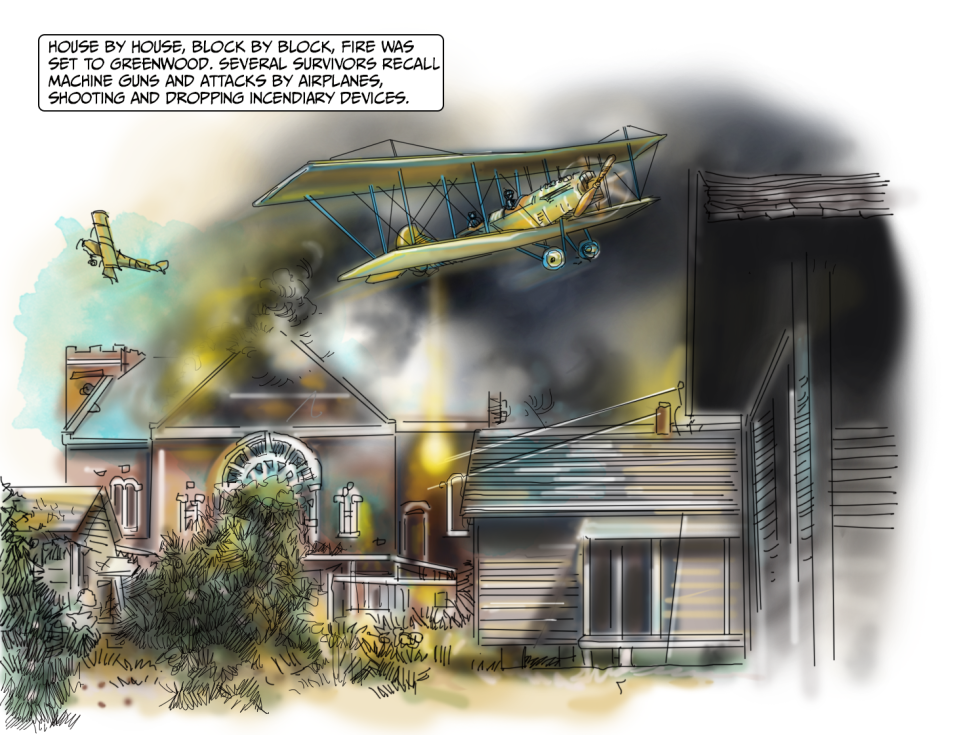

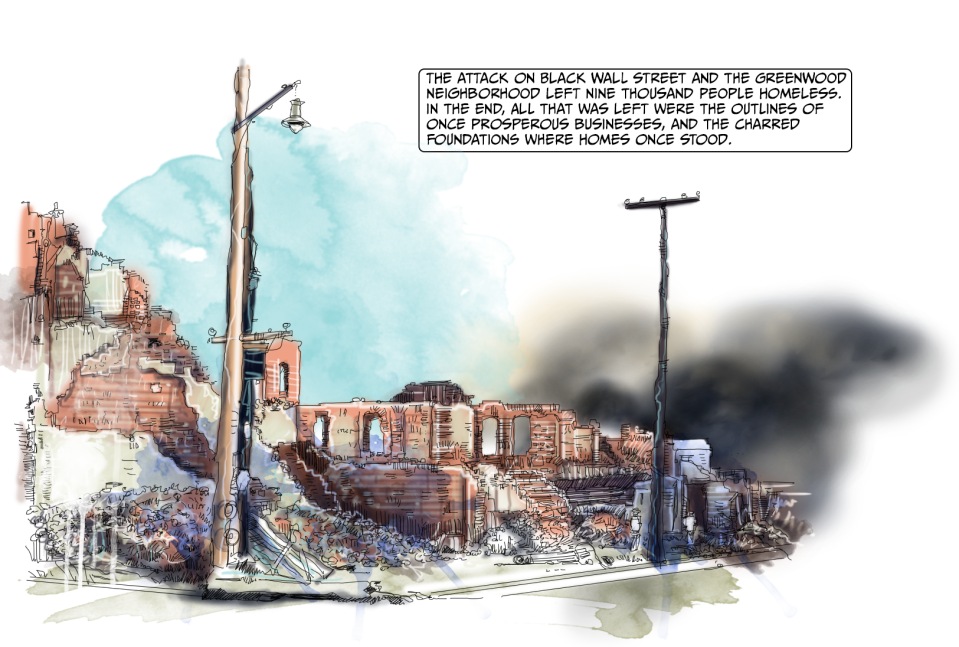

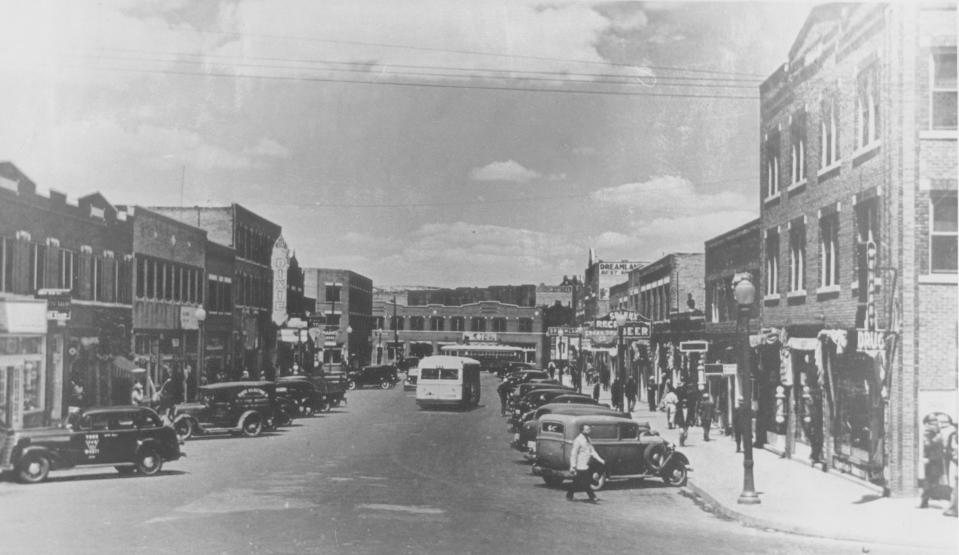

In the early 1900s, the 40 blocks to the north of downtown Tulsa boasted 10,000 residents, hundreds of businesses, medical facilities an airport and more. On May 31 and June 1, 1921, a white mob descended on Greenwood — the Black section of Tulsa — burning, looting and destroying more than 1,000 homes.

The true death toll of the massacre may never be known, with the search for unmarked graves continuing more than a century later, but most historians who have studied the event estimate the death toll to be between 75 and 300 people.

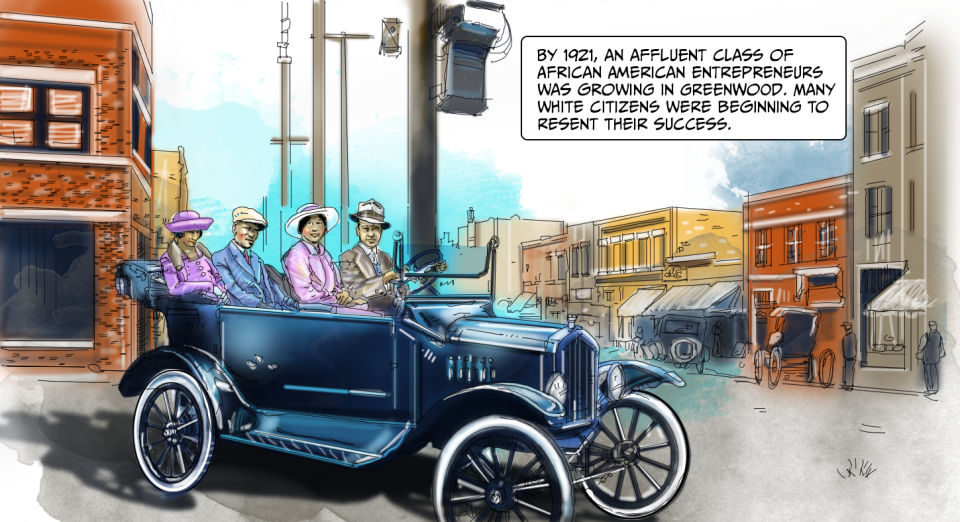

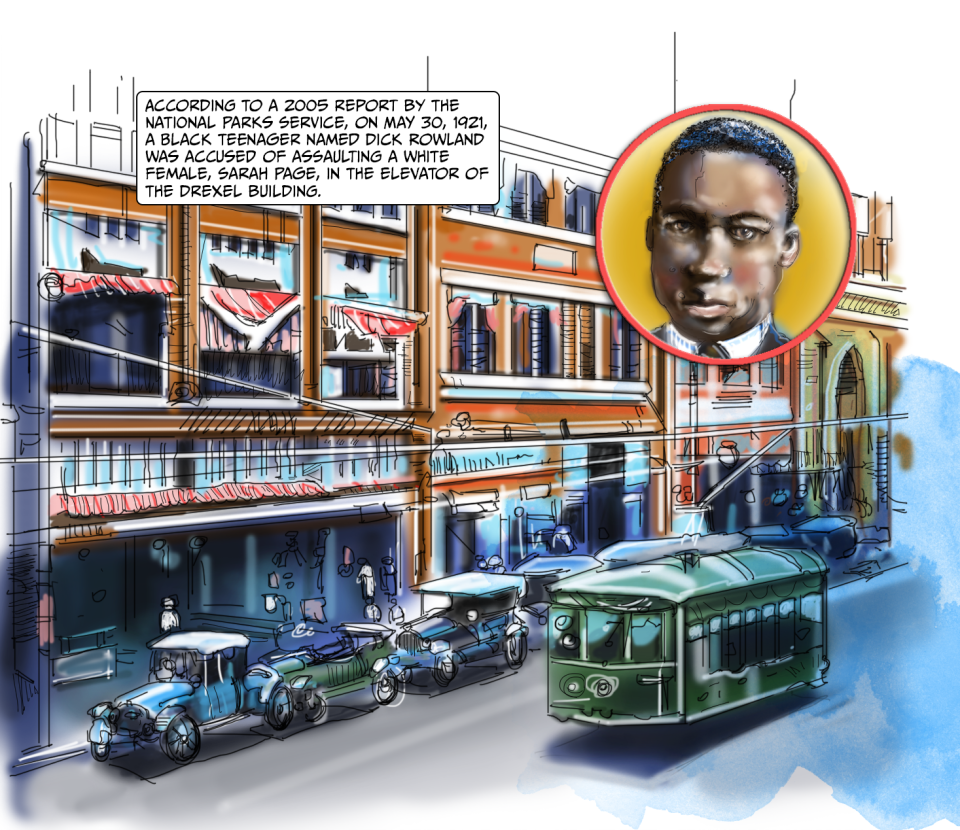

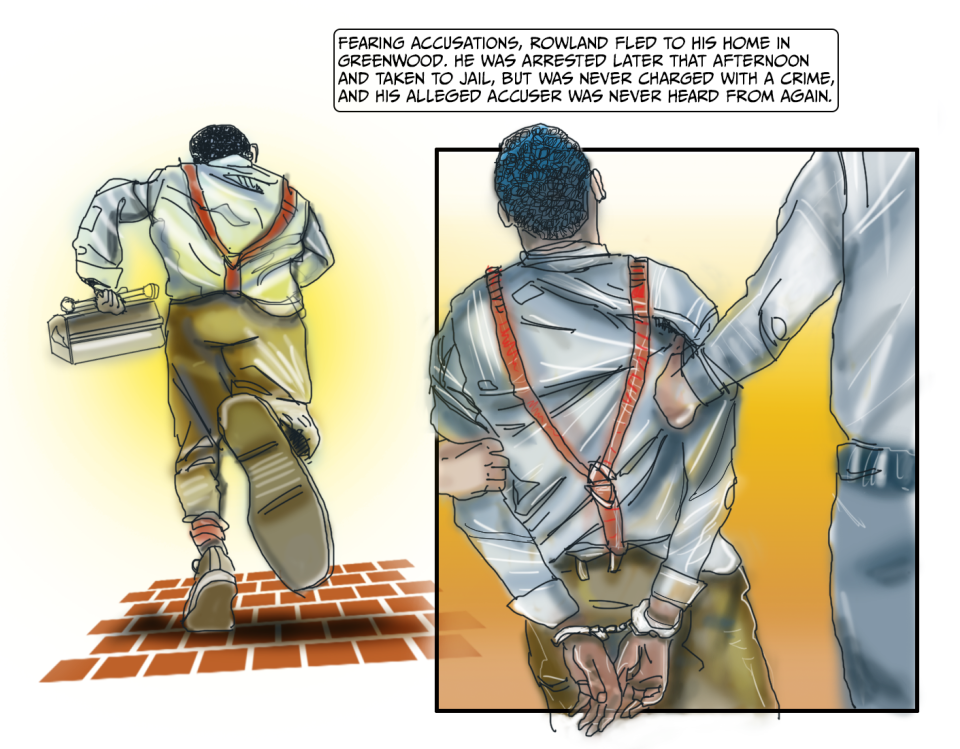

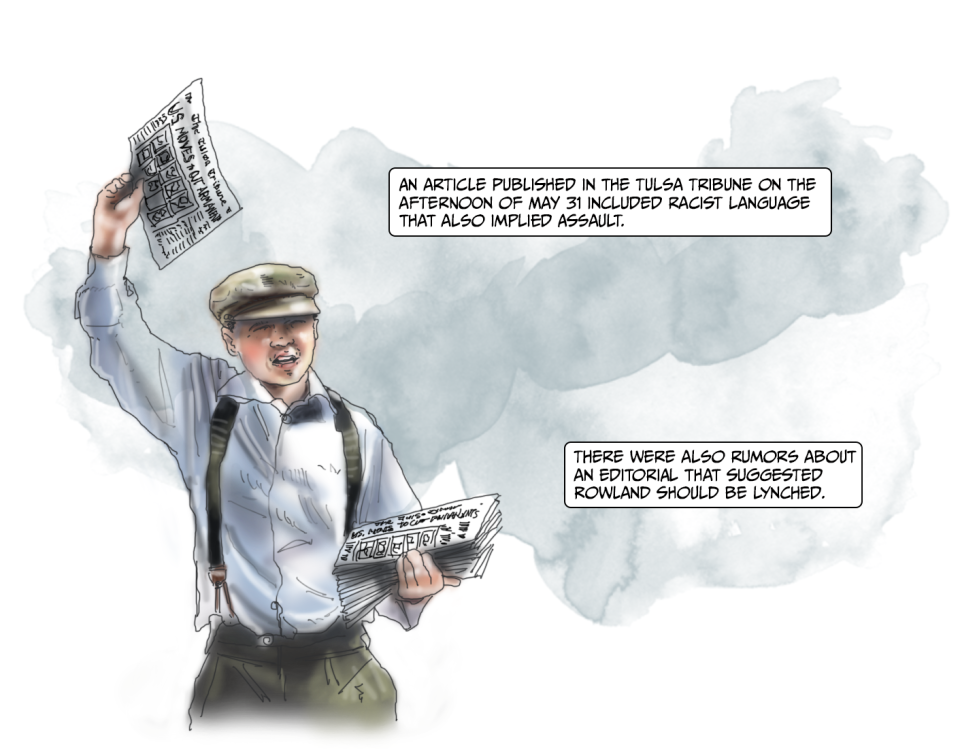

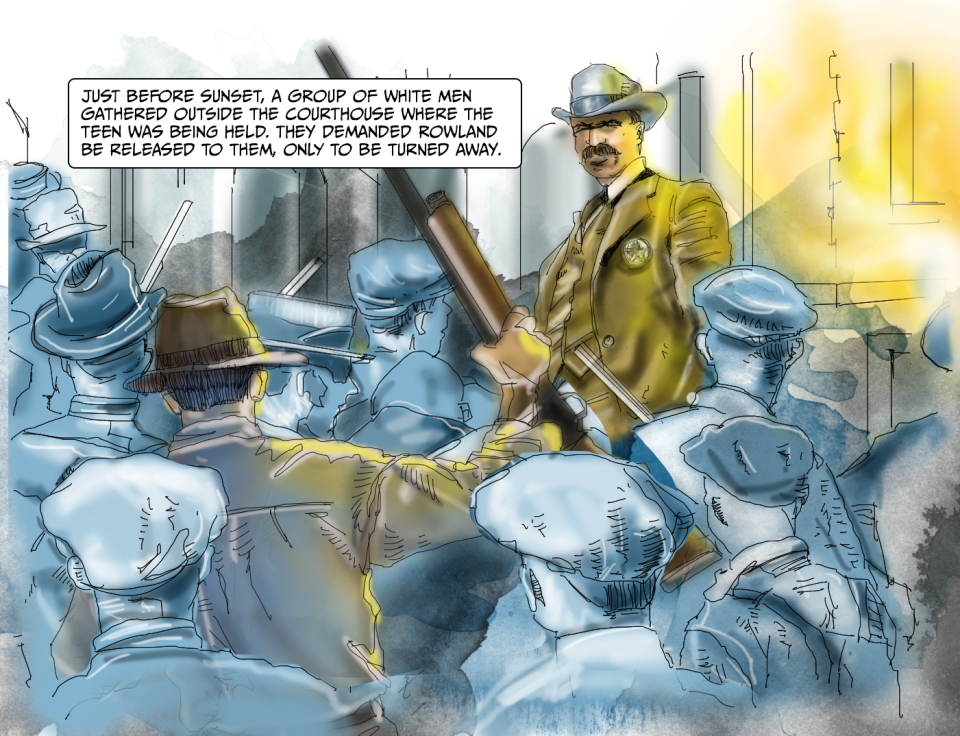

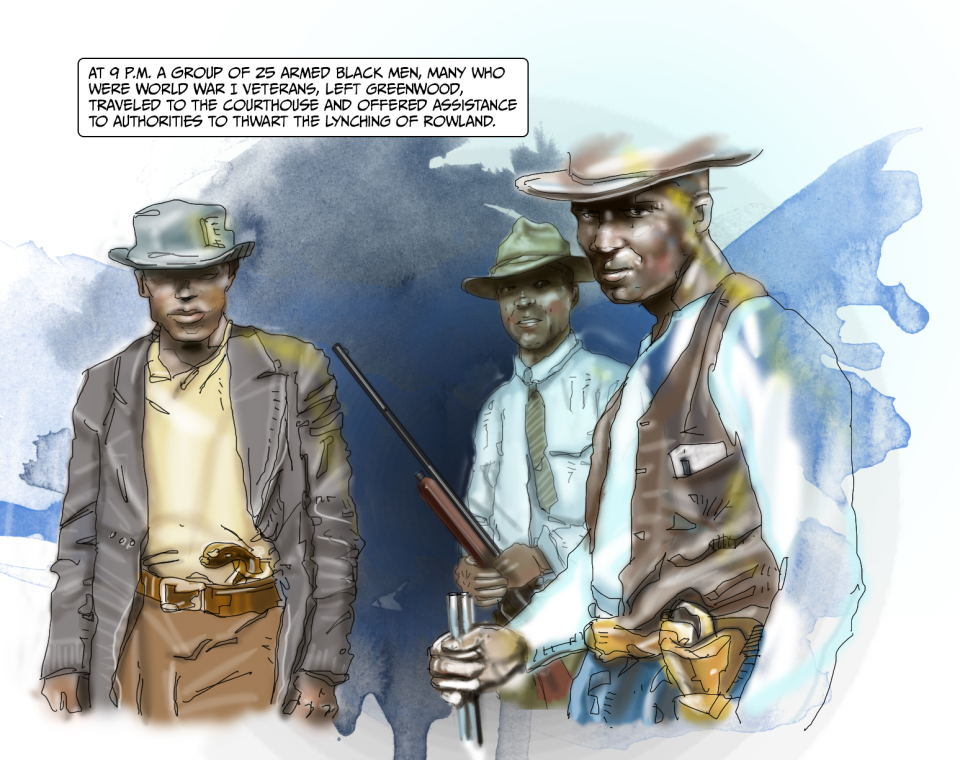

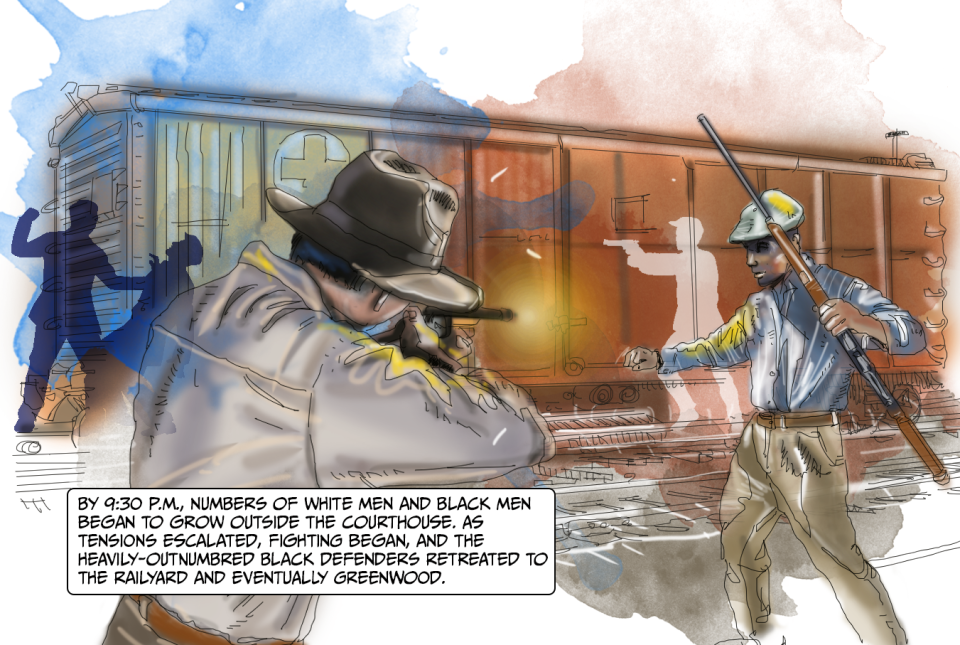

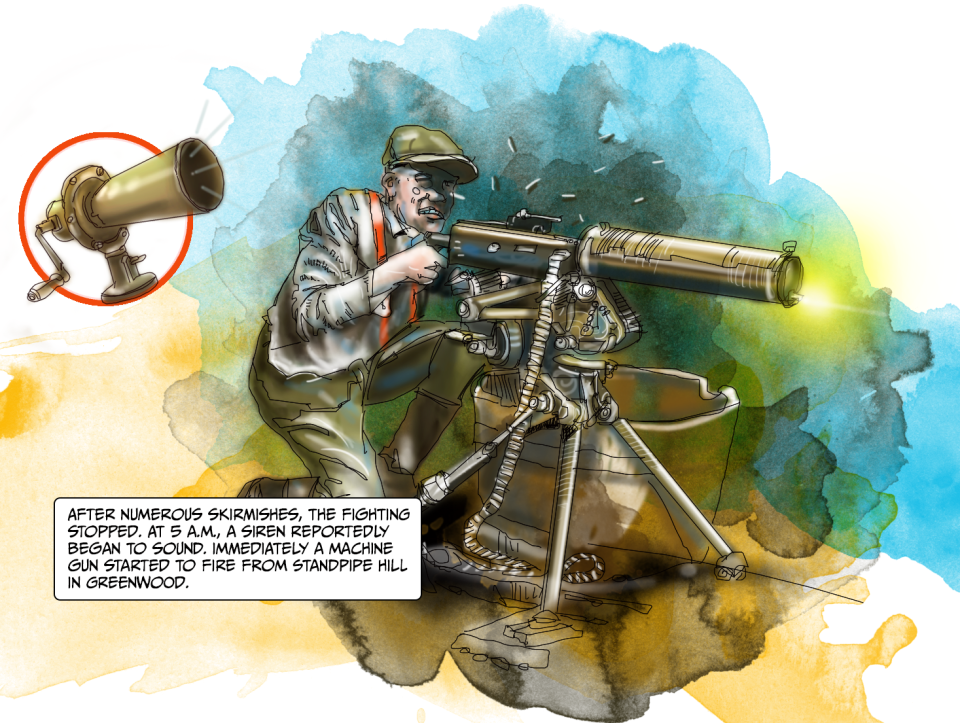

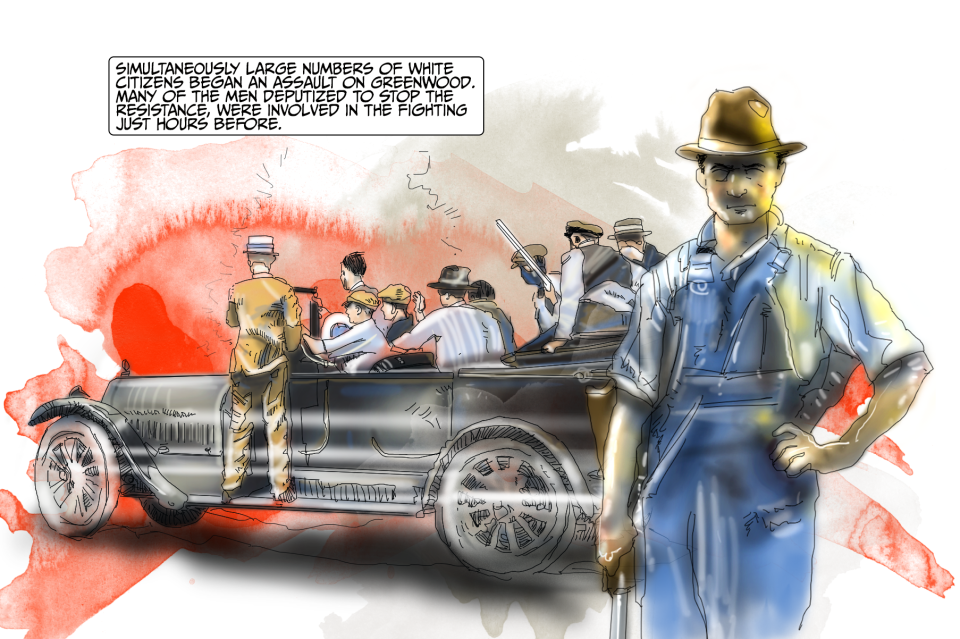

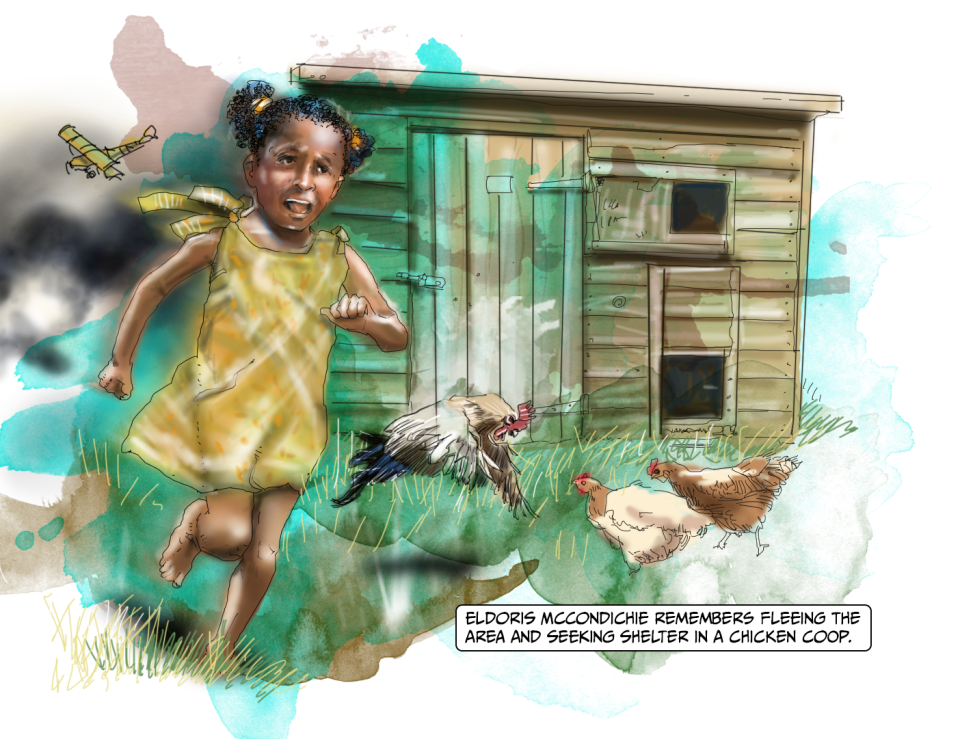

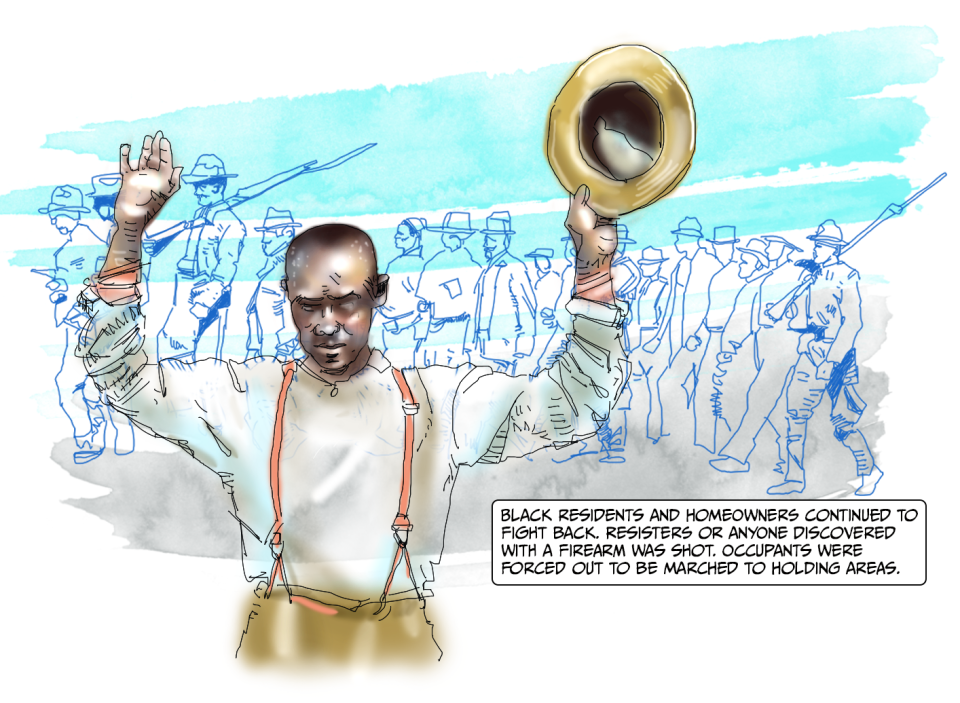

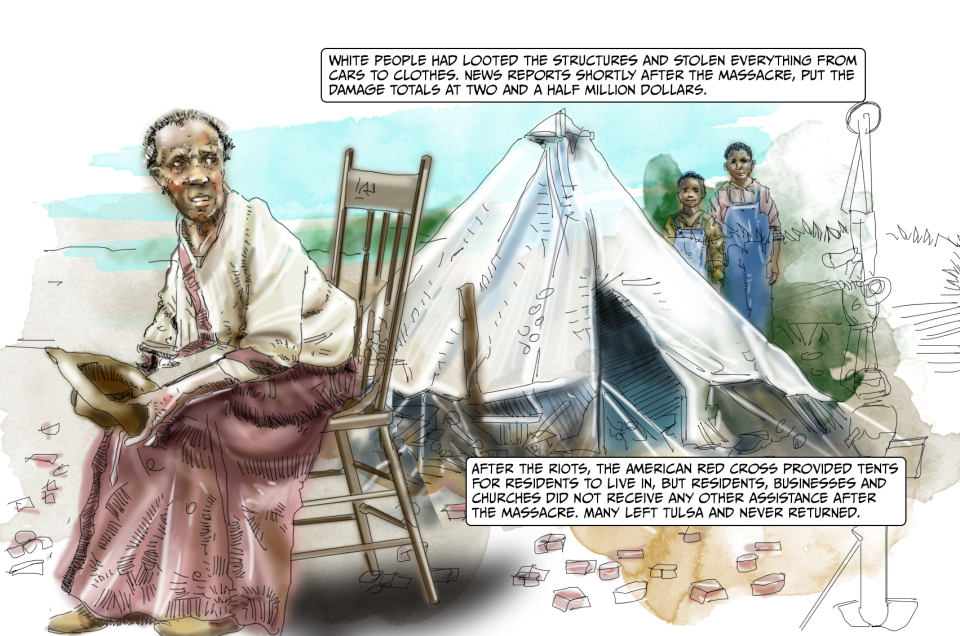

Todd Pendleton of The Oklahoman, part of USA TODAY Network, illustrated the the Tulsa Race Massacre as part of the site's coverage 100 years after the event.

From The Oklahoman ‘Dodging bullets’ and coming home to ‘nothing left’: An illustrated history of the Tulsa Race Massacre.

When did Black Americans begin to settle in Tulsa?

When was Black Wall Street created?

According to the Tulsa Preservation Commission, former slaves who gained tribal membership through marriage, and slaves owned by tribal members, first arrived during the removal of the Five Tribes in the 1830s from traditional Native American homelands in the Southeast. Then, the oil boom of the early 20th century boosted migration.

By 1908, the commercial area known as Greenwood was established.

Was Black Wall Street rebuilt?

Is there an effort to revitalize the historic district?

The Greenwood community began rebuilding just days after the destruction.

Almost a decade later, the district had more businesses than prior to the massacre — still, the area saw a decline in the mid-century caused by predatory lending, public disinvestment, urban renewal programs, and the redistribution of spending and wealth.

In the 1960s and 1970s, all but a block of the area was destroyed for construction of highways.

As of 2021, only nine buildings rebuilt in the four years immediately after the massacre remained in Greenwood, according to the Oklahoman.

In 2018, Tulsa Development Authority regained control over a portion of the land.

In 2020, the Historic Greenwood Chamber of Commerce announced that they would raise $10 million to restore Black Wall Street.

With a master plan approved by City Council in 2022, officials are now working to create a governance model for the redevelopment of 56 acres of land in the Kirkpatrick Heights and Greenwood areas to address disinvestment.

Tulsa begins community talks for possible action beyond massacre apology

City councilors started a series of conversations with stakeholders looking to inform about possible action beyond the council's formal apology in 2021 for its role in the massacre, Public Radio Tulsa reported. Attendees heard about inequities in areas such as transportation and possible reparations packages for Black Tulsans, according to the outlet.

Land transfer to new History Center

The Greenwood Rising Black Wall Street History Center — an 11,000 square foot immersive exhibition space born out of the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre Centennial Commission Center — announced on May 8 that it now owns the land it occupies. The land donation from The Hille Foundation to the center “represents one nail removed from the coffin of hopes and dreams Black people still hold onto today,” said Margo Taylor, a senior docent at Greenwood Rising.

“This land transfer is truly significant almost 102 years after the Tulsa Race Massacre,” Taylor said. “Hopefully, this may signal the start of a ‘New Mecca’ of freedom and restitution.”

Investigators make progress identifying victims of the massacre

In April, a forensic anthropologist said they are getting closer to identifying victims of the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre after city officials gathered DNA from people who believe they may be a relative or descendant of a massacre victim and others with a historical connection to Tulsa. Of the 22 remains that had DNA extraction, investigators have tracked the surnames associated with six people ‒ four male and two female, according to the City of Tulsa.

With the collected DNA, investigators tracked 19 surnames associated with at least seven states: North Carolina, Georgia, Texas, Mississippi, Louisiana, Oklahoma and Alabama. The six bodies could were not confirmed as massacre victims, but officials believe their discovery could inform where to search the cemetery to recover more victims.

More coverage from the USA TODAY Network

'Bringing people together with love,' OKC marks centennial of freedom fighter Clara Luper

President Joe Biden to mark Tulsa Race Massacre centennial by meeting survivors

Jesse Jackson says the McCurtain County sheriff should resign. No one is certain he will.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Tulsa race massacre: No longer a riot, now comes the reckoning