11/23 is Fibonacci Day!

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

(WHTM) — Born in 1170, Leonardo Bonacci, aka Leonardo of Pisa, aka Leonardo Bigollo Pisano (‘Leonardo the Traveller from Pisa’) was one of the greatest European mathematicians of the early Middle Ages. Not until centuries after his death did he come to be known as Leonardo Fibonacci (Son of Bonacci).

U.S. students falling behind in math during pandemic, study finds

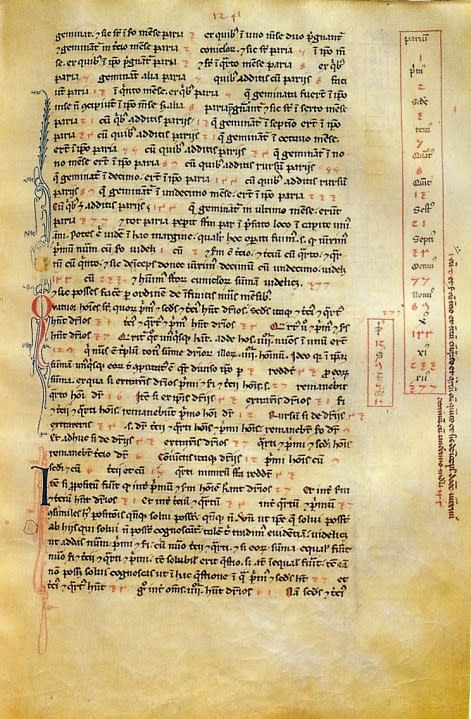

Fibonacci today is remembered for two major advances in mathematics, both found in his book Liber Abaci (The Book of Calculation), published in 1202. Ironically, he created neither of them. Even more ironically, the one for which he is best known may be the less important of the two.

Leonardo Fibonacci, 1170-(c)1240 Source: Wikimedia Commons Page from Liber Abaci, which introduced Europeans to the the Hindu-Arabic numbering system. Source: Wikimedia Commons The Fibonacci sequence in action: a channeled whelk Channeled whelk from the side. Fibonacci sequence: seeds grow out in spiral formations Sunflower seeds also grown by the Fibonacci sequence. The luminous heart of the galaxy M61 dominates this image, framed by its winding spiral arms threaded with dark tendrils of dust. As well as the usual bright bands of stars, the spiral arms of M61 are studded with ruby-red patches of light. Tell-tale signs of recent star formation, these glowing regions lead to M61’s classification as a starburst galaxy. Though the gleaming spiral of this galaxy makes for a spectacular sight, one of the most interesting features of M61 lurks unseen at the centre of this image. As well as widespread pockets of star formation, M61 hosts a supermassive black hole more than 5 million times as massive as the Sun. M61 appears almost face-on, making it a popular subject for astronomical images, even though the galaxy lies more than 52 million light-years from Earth. This particular astronomical image incorporates data from not only Hubble, but also the FORS camera at the European Southern Observatory’s Very Large Telescope, together revealing M61 in unprecedented detail. This striking image is one of many examples of telescope teamwork — astronomers frequently combine data from ground-based and space-based telescopes to learn more about the Universe.

Let’s start with the thing he’s best known for, the Fibonacci sequence. Known to Hindu mathematicians centuries before Fibonacci introduced it to Europe, it’s a simple idea, involving nothing more complicated than basic addition. Start with any two numbers, add them together, then add the result to the second number, and repeat like so:

0+1=1, 1+1=2, 2+1=3, 3+2=5, 5+3=8, 8+5=13, 13+8=21, and on and on.

Get daily news, weather, breaking news, and alerts straight to your inbox! Sign up for the abc27 newsletters here

Simple, yes, but obviously a mathematical curiosity of no practical value, right?

Well, it turns out the Fibonacci series shows up in all sorts of places, from plant seed pods to sea shells to spiral galaxies. The sequence gets applied to many aspects of science, engineering, software design, and even economics.

Harrisburg STEM students win national Cal Ripken STEM contest for COVID-blocking curtain

So why do I say the Fibonacci sequence is his second most important contribution to mathematics? Because this is what Liber Abaci is really about:

0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9

It was Leonardo Bonacci who introduced the European world to the Hindu-Arabic number system-the same one we use today.

As a boy, Leonardo lived for a while with his father, a customs official, in Béjaïa, Algeria. There, Arabian tutors introduced the young Leonardo to the Hindu-Arabic numeral system. The boy quickly grasped how much more efficient this method was than the clunky, unwieldy Roman numerals used in Europe. To say he was enthusiastic is an understatement; he would spend much of his life popularizing the Hindu-Arabic system, starting with Liber Abaci.

Not that progress was fast; back then “publishing” a book meant having a scribe meticulously and laboriously transcribing it by hand. (China and Korea had been printing books since the first millennium C.E., but in Fibonacci’s Europe the printing press was a couple of centuries in the future.) Word of the new math spread slowly, but spread it did. By the 1400’s the Roman Numeral system was on its way out.

A lifetime shattering glass ceilings in math and science for Black women

Would Arabic numbers have replaced Roman numerals in Europe, even without Bonacci’s book? Possibly, in fact, probably. It was already spreading through the port cities of the Mediterranean and would have eventually seeped its way up to northern Europe. But by writing his book, Leonardo Bonacci, Fibonacci, Bigollo Pisano jumpstarted (to use a term he wouldn’t understand) a process that otherwise might have dragged on for many more centuries.

And if you’ve ever actually tried to use Roman numerals for anything, then you know we owe Fibonacci our deepest thanks and heartfelt appreciation.

By the way, you have figured out why they picked 11/23 for Fibonacci Day, haven’t you?

For the latest news, weather, sports, and streaming video, head to ABC27.