At 113, she's California's oldest native. She got through a tough 2020 and is still going strong

There were roughly 2.16 million people living in California in 1908. Only one of them is known to still be here, alive and breathing in the Golden State.

Through 21 presidential administrations, two once-in-a-century pandemics, the fall of foreign empires and the birth of a thousand new ways of life, she has quietly gone about her daily business in Mendocino and Sonoma counties.

Edie Ceccarelli, who turned 113 earlier this month, is believed to be the oldest living native Californian in the state. Her birthday has become something of a minor holiday in the Northern California town of Willits, where community members have gathered for birthday blowouts since she turned 100 back in 2008.

“We’re a small town,” said Willits resident and family friend Marnye Sylvander. “She’s kind of an icon for us here.”

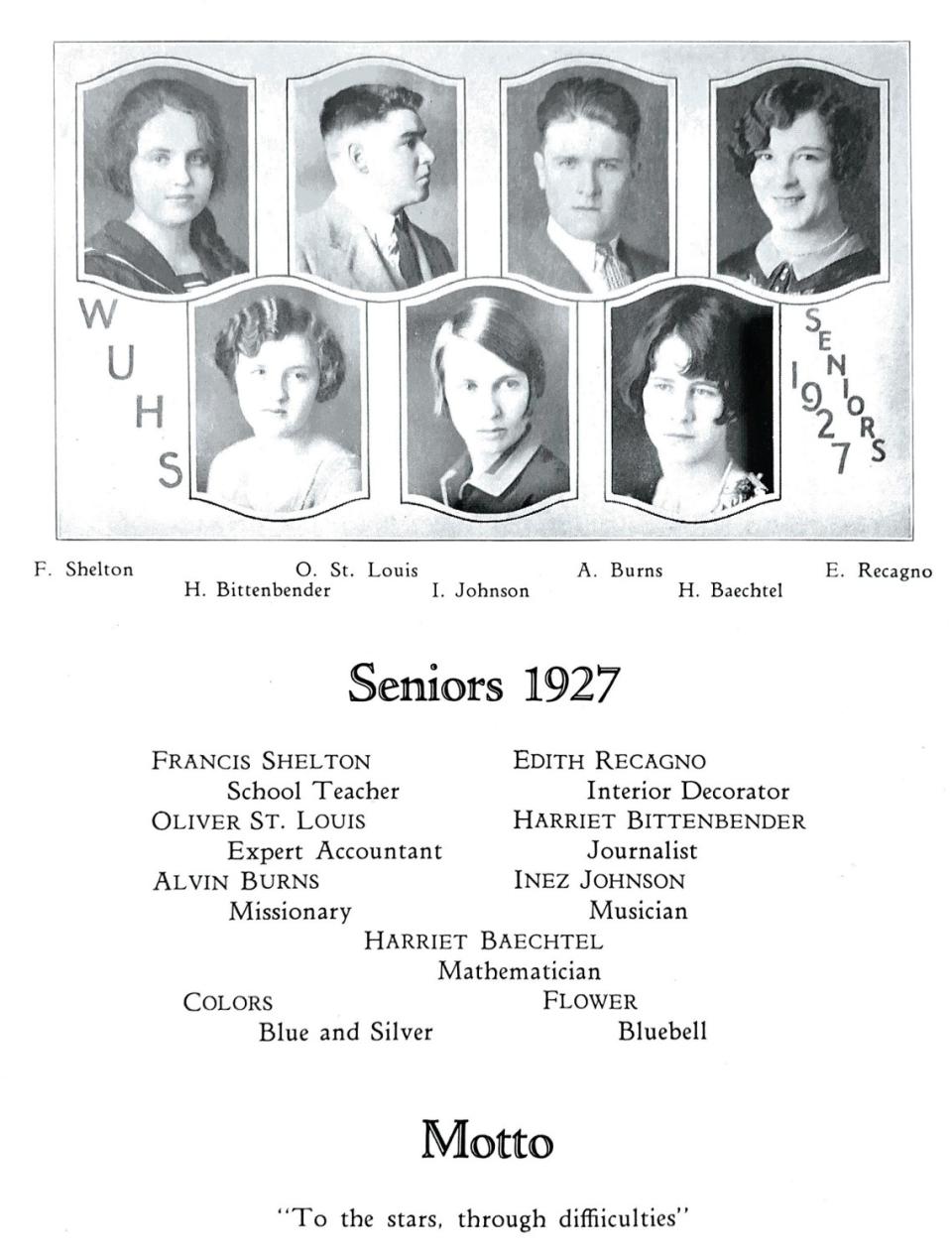

When Ceccarelli (nee Recagno and, later, Keenan) was born on Feb. 5, 1908, in Willits, women did not have the right to vote. Ceccarelli was delivered at home, in a house without running water or electricity that her Italian immigrant father had built with his own two hands. Henry Ford would introduce the first Model T automobiles later that same year.

At the time, downtown Willits would probably still have borne visible damage from the 1906 San Francisco earthquake, according to Historical Society of Mendocino County historian and archivist Alyssa Ballard.

“Right when Edith was born was really when Willits was getting connected to the outside world,” Ballard said, noting that the newly constructed Northwestern Pacific Railroad wouldn’t offer regular passenger transport to the town until around 1910.

Ceccarelli’s father, a lumber worker who helped build the railroad, sold groceries by horse and buggy during the early years of her childhood. He opened his grocery store in 1916, as battles raged abroad and the U.S. prepared to enter the War to End All Wars. Life was slow back then, as Ceccarelli would later tell a local paper. The family sat by the oil lamp in the evenings. Some days, she and her younger brothers would earn 50 cents a day, picking potatoes in the surrounding valley.

By the next World War, Ceccarelli was a mother in her early 30s, married to her childhood sweetheart, Elmer Keenan, and living with him and their daughter in Santa Rosa.

Richard Nixon was still in the Oval Office when the couple finally moved home to spend their golden years in Willits, after Keenan retired from a long career at the Santa Rosa Press Democrat. That was 50 years ago.

Ceccarelli is a member of an elite club of supercentenarians, or people older than 110. Robert Young, co-director of the Gerontology Research Group, compared life after 110 to the “death zone” climbers face near the peak of Mt. Everest. It is incredibly rare to reach supercentenarian status, and rarer still to surpass it.

Young’s group, which has not officially verified Ceccarelli’s age, catalogs the world’s oldest living people. According to his estimates, Ceccarelli is “approximately the 40th oldest person in the world.” She is not the oldest state resident — that distinction belongs to Nebraska-born Berkeleyan Mila Mangold, also 113 — but Ceccarelli is believed to be the oldest native Californian still living in the U.S. (Maria Branyas, who was born in 1907 in San Francisco, is technically the oldest native Californian, but she moved to Spain in 1915 and still resides there.)

Since Ceccarelli turned 100, each additional trip around the sun has been cause for celebration in Willits. But the pandemic necessitated a different kind of party from the banquets of years' past. Cue hundreds of cars, firetrucks, bicyclists, pedestrians and a few flag-waving horseback riders, all making their way past the Willits care home where Ceccarelli now resides. On Feb. 5, 2021, the birthday girl wore a tiara and a borrowed fur coat as she waved from a patio during the socially distanced car parade.

Cousin Evelyn Persico had worried that Ceccarelli, who lives with dementia, might feel abandoned during the pandemic, with her usual visitors barred. But her cousin has always loved a parade. "It was just a great day for her," Persico said.

To defy death is to endure a long onslaught of loss. Ceccarelli, who lived independently until she was 107, has outlived six younger siblings, two husbands, a daughter and three grandchildren. The entire cast of characters from her early life are now gone, as is the world she once knew.

“She's outlasted all of her dance partners,” observed Willits Mayor Madge Strong, who took part in the birthday car parade from her white Prius.

But even into her centenarian years, Ceccarelli’s drive for connection and joy remained irrepressible.

After her longtime local companion and dance partner died at 86, she published an open letter in the local newspaper, looking for someone to waltz with her. “I, Edith Ceccarelli — also known as 'Edie' by her family and a multitude of friends — would like to keep on dancing,” she wrote. She was 104 at the time, and included her phone number so prospective dance partners could get in touch.

There is no single key to longevity, though the gerontology researcher said there are a few commonalities. According to Young, the world’s oldest people tend to be female, have kept their minds and bodies active and have a healthy body weight. They also tend not to get too upset about the small things.

Persico said that in the past, her cousin has attributed her longevity to her love of red wine with dinner, long walkabouts in downtown Willits and "good Italian genes."

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.