12 days that changed the Rolling Stones forever

Think of the groups considered major threats to Western civilization and you’re likely to single out scourges like ISIS. Nowhere on that list would you put the Rolling Stones who, today, seem about as threatening as the Boy Scouts of America. Yet, 50 years ago, many in the old guard viewed them as nothing less than a metastasizing cancer on the moral order. More specifically, they were seen as Satan-worshipping, drug-promoting, gender-defying sexual omnivores, with a bent towards political anarchy. It was an image the band gleefully seeded — as well as one they greatly amplified right at the end of 1968.

Over the course of three key projects, released late that year, the Stones transformed from their teasing, earlier guise as rock ‘n roll “bad boys,” into something far more potent, deep, and new. Between Nov. 30 and Dec. 11 of 1968, the Stones starred in the avant-garde movie Sympathy For The Devil, directed by the French New Wave pioneer Jean-Luc Godard; issued their most defiant work, Beggars Banquet; and filmed a legendary, and long shelved, all-star TV special, Rock ‘n Roll Circus. With those three moves, the Stones morphed from mangy rock stars into what seemed at the time like cultural revolutionaries. They became bell weathers of a new philosophy that gorged on hedonism and luxuriated in creativity. In short, they became the Rolling Stones of myth, an act worthy of the tag they subsequently concocted for themselves: “The World’s Greatest Rock ‘n Roll Band.”

Heard in its golden anniversary edition (out Nov. 16th), Beggars Banquet sounds as bracing and brutal as ever. Even its original cover promised subversion: They shot it inside a filthy bathroom, though the censored American version subbed in a mock-wedding invitation for the grime. The album’s ten tracks, which roiled over 40 minutes, instantly banished the band’s eight previous albums to the past, pointing the group towards a future that not only signaled their personal peak (from Beggars through Exile On Main Street), but also helped usher in the most sanctified era of rock itself (1968-’72).

After all, it wasn’t just the Stones who were evolving exponentially. The entire culture was. If you listen to the sounds, and follow the fashions, from 1967 to ’68, you’ll notice that nearly every act grew their hair (even) longer, made their music (even) louder, and promoted messages that were that much harder. The Stones simply did all three better.

The upgrade came at a crucial time. The year before, they made one of the rare bum moves in an otherwise sterling career, as Their Satanic Majesties Request found them exploring a flouncier, fussier sound than their blues-rock muse. A psychedelic reach, Satanic was widely seen as their answer to the Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper, a flawed strategy from the start. Instead of countering the Beatles’ sweeter sound with something rougher, as they had done up until that point, now it seemed they were trying to mirror them — and clumsily at that. With Beggars the band both returned to a rawer sound and created a wholly fresh one. Their instrumentation, subject matter, even the essential vibe of Beggars, broke with their earlier patterns. It all felt looser, freer, wilder — yet, at the same time, ruthlessly honed.

Ironically, Beggars was largely acoustic-based, not an obvious perception given how ruthlessly parts of it rock. Even the fiercest tracks, like “Sympathy For The Devil” or “Street Fighting Man” make crucial use of acoustic instrumentation. Other key songs are, at root, ballads, drawn from country and folk. Songs like “No Expectations,” “Dear Doctor” and “Factory Girl” argue for the Stones to be seen as early promoters of the roots rock sound later known as Americana — a creation widely credited to the Band for songs they’d released just five months prior, on Music From Big Pink.

The intimacy and beauty of the Stones’ ballads brought individual listeners closer to them than they ever had the chance to get before. Meanwhile, the force of their rockers promised to bind fans into a global movement. The latter found its ultimate anthem in “Street Fighting Man.” Never had Keith Richards weaponized his guitar so lethally. His opening riff, a sift of acoustic and electric axes, translated revolution into sound, in the process ranking “Fighting” up with the most confrontational creations in rock history. While the Beatles’ “Revolution” (released four months earlier) questioned the morality of such an uprising, the Stones bought right in, dismissing any “compromise solutions.” The band dug in further with “Salt of The Earth,” an enduring working-class anthem.

Overall, however, the album swerved from literal politics to favor a vague brand of anarchism. You hear it in the deep smut of a cut like “Stray Cat Blues,” which featured the group’s filthiest playing, not to mention its most leering lyrics, tracing a three-way involving its narrator and two underaged girls. But the biggest blast of contrariness came in “Sympathy For The Devil.” Jagger sang the song from Satan’s point of view, though he did so more to satirize human foibles rather than to express any allegiance to the underworld. The track represented a masterpiece of layering and construction, corralling a feral series of samba beats, war cries, rumbling bass lines, and scathing guitar solos into something both hallucinogenic and whole.

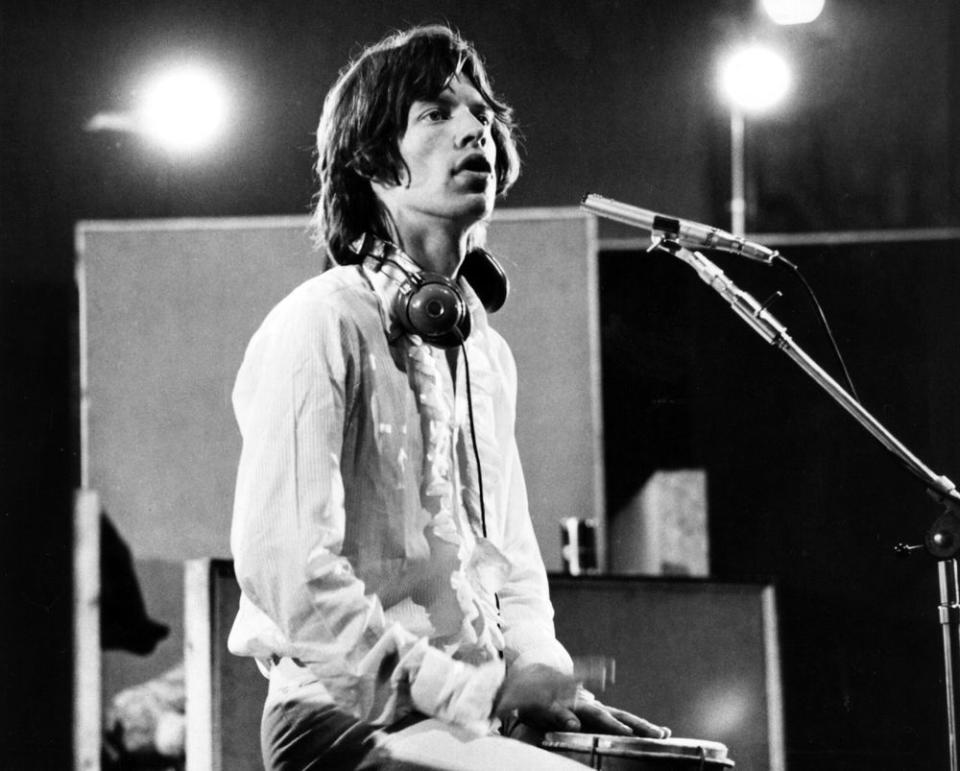

The process of creating that track forms the center of Godard’s movie known by the same name, though the director had wanted to call it One Plus One. (It’s newly available in a Blu-Ray version under both titles.) While relatively few fans saw this, shall-we-say, challenging film, the mere fact of its existence burnished the Stones’ new pretense as cutting-edge radicals. Its “story,” such as it was, intercut footage of the band figuring out the song in the studio with scenes of things like the Black Panthers reading revolutionary texts, a woman defacing property with graffiti, and a voice-over which mumbles a subversive novel. It’s a mess of ideas and mis-directions which, if nothing else, nails the edginess of its time. Godard’s film also captures the song’s topicality. The lyric which the band rehearses in the main part of the film refers to a single dead “Kennedy.” The final version turns that name plural, reflecting the assassination of Bobby Kennedy, which had taken place during the recording process.

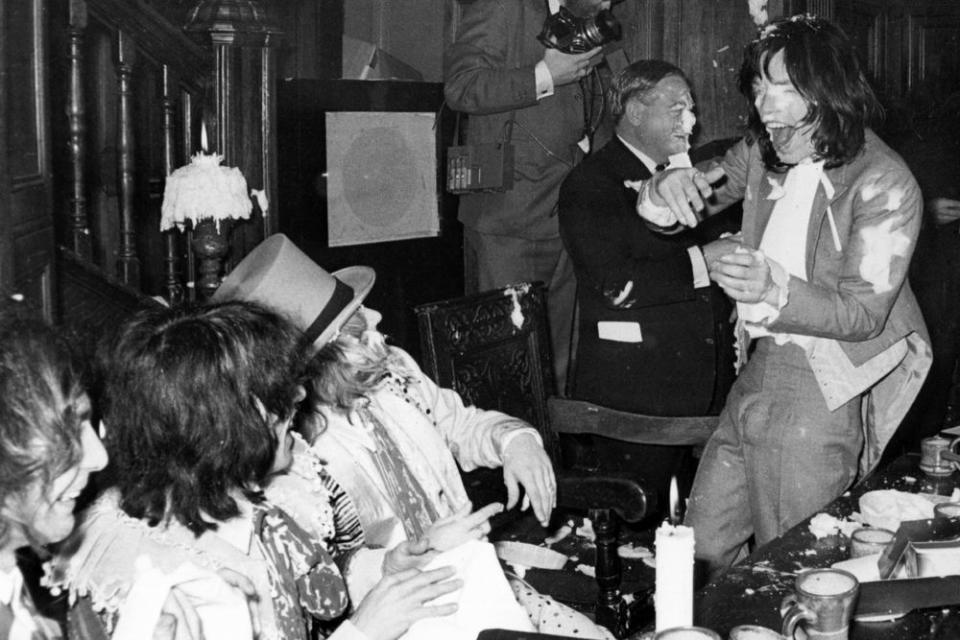

Five days after the film was released, the Stones taped “Rock ’n Roll Circus” — though, sadly, it wasn’t seen by the public for another 27 years. The group had shelved it, believing their exhaustion during the taping resulted in them being upstaged by the Who. Whatever flaws in the show, it still provided a riveting snapshot of a pivotal time. The Stones never looked cooler or more colorful. Jagger, in particular, modeled a radically new brand of male beauty, one that helped pioneer the age of androgyny three years before Bowie had the notion.

Throughout the show, there are strong and rare performances, including one featuring Taj Mahal’s classic band, which boasted the wily guitarist Jessie Ed Davis, and another by Jethro Tull, which offers the only physical evidence of the fleeting time guitarist Tony Iommi spent with them, one year before he formed Black Sabbath. There’s also a one-time-only superstar band operating under the name Dirty Mac, which corrals John Lennon, Eric Clapton, Keith Richards, Hendrix drummer Mitch Mitchell, and a shrieking Yoko Ono. It must be heard to be believed.

Even so, the Stones’ six songs steal the show. They dip into the past with “Jumpin’ Jack Flash” and shoot the future with “You Can’t Always Get What You Want,” which wouldn’t find a home on an album for another year. The core of their performance, however, lies in the four songs from Beggars, including an eight-minute “Sympathy,” which shows the Stones embracing their new persona: one dirtier, darker, and far more threatening than before.

Ten years later, the Stones would release a song named “Respectable,” whose lyrics wryly admitted that they had, by then, been utterly co-opted and neutered. That’s hardly a surprising turn. It’s the inevitable fate of all artistic outlaws who suffer, and enjoy, the culture’s embrace. Regardless, what the Stones created on Beggars set a template for menace and joy that anyone, at any time, can revel in, and, hopefully, one day re-invent.