144 years and counting: MSU experiment still providing data

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

GRAND RAPIDS, Mich. (WOOD) — Researchers at Michigan State University are learning more about the intricacies of seeds and doing their part for an experiment that stretches back more than a century and is scheduled to last until the next one.

For more than two years, MSU scientists have been analyzing a group of seeds excavated in April 2021 as part of the “Beal Seed Experiment.” Lars Brudvig, a community ecologist and professor at MSU who participated in the latest dig, says it was started by botanist William J. Beal in 1879 — a man who was a leading science mind for his time.

“Dr. Beal was one of the first faculty members at Michigan State,” Brudvig told News 8. “He helped start up the Botany Department. He was the first curator of the herbarium here and he did a number of different studies.”

Grace Fleming, an assistant professor who also is part of the experiment, said Beal is one of the first researchers to bring science to the farm fields.

“He was instrumental in connecting agriculture and science. They used to be (held in different circles). And there was this big argument at the time of, ‘We can use the scientific method to do farming better, right?’” Fleming said.

Watch: Spartan scientists unearth Beal Seed Experiment

The Beal Seed Experiment looks to answer one key question: How long do farmers have to work on digging up weeds and their seeds before they will stop coming back? Beal gathered up seeds of 20 different common farm weeds, layered them with soil into 20 small glass bottles and buried them. The original plan was to retrieve one bottle every five years and test those seeds to see if any would germinate.

Beal laid out the experiment, hoping it would live on long after his death and help provide more answers for farmers in the future. It will actually go on longer than he even dreamed.

“At some point, the research team decided to extend (the time between digs) to every 10 years. Then in 1980, they decided to go to every 20 years because clearly some things can live for a really, really long time,” Brudvig said.

X DOESN’T MARK THE SPOT

While the experiment is pretty simple on the surface, actually finding the bottles takes some intricate work. The dig site, somewhere on the MSU campus in East Lansing, is kept a secret to prevent other people from interfering with the experiment or tampering with the seeds.

“We have a map that helps us locate the (dig site). It’s not otherwise marked, but we are able to use certain features on campus to triangulate to the location,” Brudvig said. “The people who need to know the location know the location: All of us researchers and then key people in the facilities group on campus. We want to make sure there is not accidentally a new water pipe or a building put there.”

That secret, however, was nearly lost before Brudvig and Fleming were brought in on the project.

“(Professor Emeritus) Frank (Telewski) actually came up to a couple of us, it must have been about 2015 or 2016. He said we need to start planning the next dig and (gave us) a copy of the map,” Brudvig explained. “He wanted to make sure that they were in a few different people’s hands, and I think he said something like, ‘Who knows? Maybe I will get hit by a bus or something.’ Something sort of tongue in cheek, but then he had a stroke. He made a virtually full recovery, which is amazing, but that could have been the breaking line in the experiment.”

Sign up for the News 8 daily newsletter

Every dig is done in the middle of the night, but that’s not solely to continue the air of mystery. It also protects the seeds and the boundaries of the experiment.

“We have additional bottles that are still underground that are going to be dug up in future years. One big cue for the germination of seeds is sunlight. We don’t want sunlight to accidentally shine down on the 2060 bottle and accidentally start seeds germinating prematurely,” Brudvig said. “We even use special headlamps that don’t shine white light on (the bottles).”

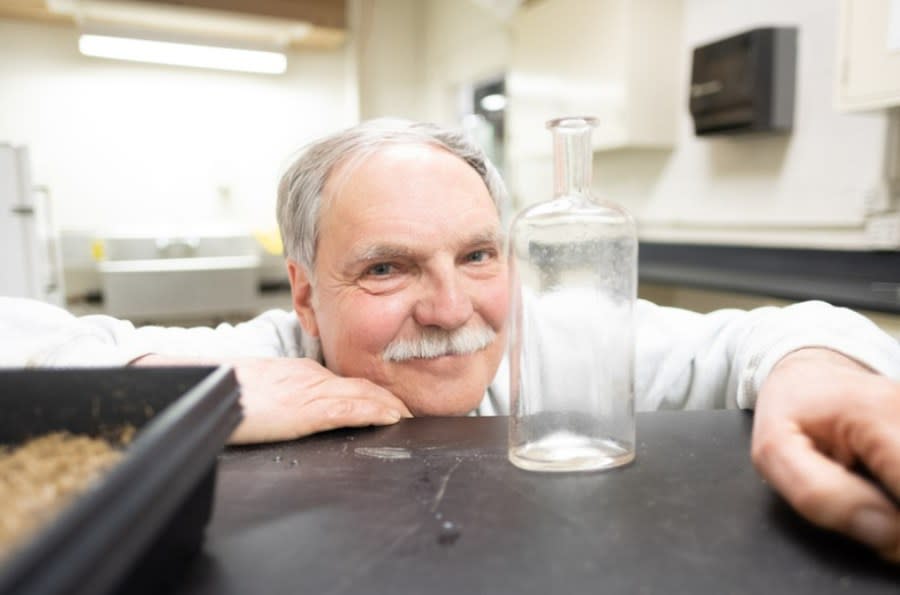

Researchers using measuring tape to find the exact location of the “Beal Bottles” that are buried in a secret location on Michigan State University’s campus. (Courtesy Michigan State University) Professor Lars Brudvig digs for a Beal Bottle to continue the seed germination study first started by Wiiliam J. Beal, over 140 years ago. (Courtesy Michigan State University) Researchers pose for a photo at the dig site to retrieve one of the bottles from the Beal Seed Study. (Courtesy Michigan State University) A researcher holds a bottle containing seeds that was buried by William J. Beal more than 140 years ago. (Courtesy Michigan State University) Michigan State University researchers hold up a small, glass bottle that was buried by William J. Beal in 1879. This bottle was unearthed in 2021. (Courtesy Michigan State University) Frank Telewski, the curator of the W. J. Beal Botanical Garden and Campus Arboretum, pulls the seeds and soil from the Beal Bottle. (Courtesy Michigan State University) Frank Telewski, the curator of the W. J. Beal Botanical Garden and Campus Arboretum, spreads seeds from the Beal Bottle into a tray to see how many will germinate. (Courtesy Michigan State University) Frank Telewski, the curator of the W. J. Beal Botanical Garden and Campus Arboretum, poses with an empty bottle used in the 1879 Beal Seed Experiment. (Courtesy Michigan State University) Moth mullein sprouts from a seed that was stored and buried in 1879 by MSU botanist William J. Beal. (Courtesy Michigan State University) Moth mullein sprouts from a seed that was stored and buried in 1879 by MSU botanist William J. Beal. (Courtesy Michigan State University)

FROM THE LAND TO THE LAB

The latest dig was done in April 2021 — one year later than initially planned because of the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. After the excavation, the bottle was brought to the department lab and emptied into a tray. The seeds are routinely watered and put on a special light cycle to resemble day and night.

“When a plant starts to germinate, we start to follow it. When the plant starts to get big enough, we will kind of carefully get it out of the tray and put it into its own pot so that it can continue to grow,” Brudvig said. “We attempt to grow every single one of the pants that germinates all the way to (the flowering stage) so that we can have a full, complete specimen. This year we went even a step further to use molecular tools to really pin down the idea.”

Every bottle has roughly 50 seeds each of 20 different plants. Every round of seeds yields different results. This latest experiment saw 20 seeds germinate, including an unexpected hybrid.

“We have just one species that we saw germinating — verbascum blattaria — (also known as) moth mullein,” he said. “We were able to confirm that one of these was actually a hybrid. One of the 20 was a hybrid between moth mullein and common mullein. They are species that are in the same genus, but they are different species.”

That doesn’t mean the seeds uncovered in 2040 won’t yield different results.

“The very first bottle that was buried for five years had (approximately) 340 seeds germinate out of a thousand,” Fleming said. “There are some species that have never germinated ever. … They could just be a very, very short-lived species. Or it could be that the seeds were all kind of bunk when they were put in.”

WATCH: Timelapse of germinating seeds from Beal Seed Experiment

Fleming remembers taking a step back in the lab and trying to digest the fact that she was adding her name to a historic scientific study.

“It was just thrilling. I got to be the first one to take sand out of that bottle in this cold room by myself at like 5 a.m. It was really overwhelming. Like Lars was saying, the last person handling this material was this famous, dynamic person that I’ve only known from his writing,” Fleming said. “To touch this thing that is connected him, to smell it. It really is very powerful.”

For Brudvig, it comes down to the wide-ranging impact that this simple experiment has made on agriculture.

“It has been really interesting to see the ramifications of this research that have developed over time,” he said. “Beal initiated the experiment to study agricultural weeds from a farming perspective. Since then, we have come to realize the importance of seeds in the soil seed bank. … (It sparks) fundamental questions in ecology and evolutionary biology, other sorts of applications as well, like the conservation of rare species of plants that we might look to preserve through our habitat management plans, or species that might invasive species that can live in the soil or seed bank. … The research has developed a much broader relevance than, I think, the initial vision foresaw.”

The next dig will be conducted in the spring of 2040. For now, how that group of seeds will respond, just like the location of Beal’s buried seeds, will remain a mystery.

For the latest news, weather, sports, and streaming video, head to WOODTV.com.