After 17 wrenching months: Verdicts, death and a witness' shocking admission

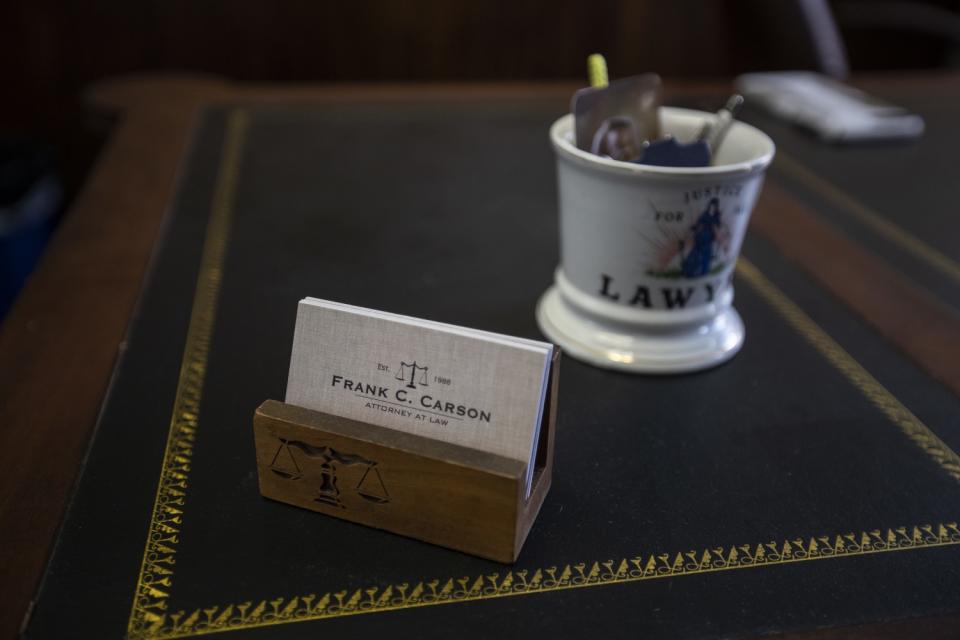

They were a year into the preliminary hearing with no visible end, and Frank Carson was close to despair. He was trapped where so many of his clients had been, alone in a chilly cell in a Stanislaus County jail. He had rebuffed every overture to cut a deal, to plead, to inform on codefendants in exchange for lenience.

But guilt pierced him. He blamed himself for the plight of his wife and stepdaughter, out on bail but charged in the so-called murder plot he had supposedly masterminded. He blamed himself for the continued incarceration of three other codefendants, former highway patrolman Walter Wells and Pop N Cork liquor store owners Baljit "Bobby" Athwal and brother Daljit "Dee" Atwal. All of them had refused to implicate Carson, telling prosecutors they had nothing to say.

“Boys,” Carson said one day, sitting before them in a courthouse holding room.

He had found a solution, he explained. He would take the blame, so they could go free. There seemed no other way out. He was in his 60s, with no kids; they were younger men, and fathers. The D.A. wanted him. What he did not tell them was that he had knotted up a sheet to keep under his pillow, to hang himself before they put him on a bus to prison.

“No, Mr. Carson,” his codefendants said. The brothers were Sikhs from the Punjab region of India. To let Carson take the blame for something he hadn’t done would dishonor the family, they explained — they’d be killed if they returned to their village.

Back into court they trudged for another week of State vs. Carson et al, hoping that visiting Judge Barbara Zuniga would assess the evidence and scuttle the case. Carson viewed the judge, a former Contra Costa County prosecutor, as biased toward the government and credulous toward its claims.

So he held small hope she would do anything when, 14 months into the prelim, prosecutor Marlisa Ferreira announced she had a big cache of evidence — including scores of audio recordings — that had not been turned over to defense lawyers. She had just found them, she said.

On one of the years-old recordings, district attorney investigator Kirk Bunch told an incarcerated Robert Woody, who became the government’s star witness, how eager the D.A. was to work with him. “We’re bending over backwards for ya,” he said. “We just want to see if you want to add to your story.”

Woody seemed to believe that detectives did not care whether his story was true or false.

“Add stuff to it if it ain’t true?” Woody asked.

This was more ammunition to attack Woody’s credibility, and the long-buried evidence confronted Zuniga with a serious problem. If she sent the case to trial, it would surely be overturned on appeal because of the prosecution’s blunder.

As the case against Wells eroded, with charges dropped from murder to conspiracy, he had been able to make bail. But Carson and the brothers remained in jail, and now the judge did an exceedingly rare thing — she released the three murder defendants on their own recognizance. “To save the case for your office,” she told the prosecutor.

And so Carson, Bobby Athwal and his brother Dee — all still facing murder with special circumstances — went home to their families after 17 months in jail. Carson returned to work, trying to rebuild his crippled law practice.

'Gosh, this was hard'

Had police ignored better candidates in the death of scrap metal thief Korey Kauffman?

The defense team attempted to shift blame to Jason Armstrong, a 47-year-old welder who lived a few miles from where Kauffman had vanished in early 2012.

In interviews with police, Armstrong denied killing Kauffman. But Armstrong did like to camp, he admitted, in the area of the vast Stanislaus National Forest where the bones had been found. He expressed contempt for the thief and believed he’d stolen a friend’s tools. And a local man told police he’d been brutally beaten by Armstrong and his friends, who suspected he’d stolen those tools with Kauffman.

So why, asked defense attorney Martha Carlton-Magaña, had the Armstrong angle been so quickly abandoned by authorities? “No search warrants,” she said. “No call detail records. No wiretaps.”

The argument left Zuniga unmoved, however. “Gosh, this was hard,” the judge said on Day 200 of the preliminary hearing in April 2017, noting the complexity of the case. “I really had a hard time getting my head around it.”

The D.A.'s case rested on Robert Woody, and the judge believed him. He had been threatened with the death penalty, but she rejected the argument that police had coerced him. Despite his many lies, she found “an overarching consistency in his testimony, which lends to his credibility.”

The judge said, “The evidence shows that it was Mr. Carson who set this whole process in motion.”

So Carson and the brothers would go to trial together. The judge believed the state’s claim that Wells had been in possession of Kauffman’s phone in the weeks after he disappeared, and Wells was scheduled for trial separately. Against Carson’s wife and stepdaughter, however, the judge found the evidence too weak to hold them.

A longtime heroin addict and former member of the Aryan Brotherhood prison gang, Michael Cooley — he of the "White Pride" and "Ladies Love Outlaws" tattoos — had been one of the last to see Kauffman alive. And it was Cooley whom defense attorneys portrayed at trial as Kauffman’s real killer.

He took the stand in June 2018. He said he saw a pyramid of aluminum pipes on Carson’s lot that day six years earlier. He said Kauffman had planned to sneak through a hole in the fence to steal them, but had never come back.

He admitted he’d been in more than one knife fight, and defense attorneys insisted that he’d killed Kauffman himself. “Don’t accuse me of killing my homeboy, dude,” Cooley snapped at one of them. “I’m telling you.”

'It's ruined my career'

At the Modesto courthouse Carson’s trial dragged on, through that summer and into winter and then into another, final summer. In no small part, the brutalizing pace owed to the nature of the D.A.'s case. Short on physical evidence, it was a jagged mosaic of testimonial fragments.

Witnesses said they had heard Carson make threats. Or had witnessed his bad temper, in one context or another. Or had seen him surveilling his junk lot from his truck down the block. Or had seen what might have been a rifle-wielding man on his property. Or had heard him say that he preferred to represent killers to thieves, because killers did it once, but thieves were incorrigible.

But only Robert Woody, who was on the stand for months, put Carson and the brothers at the supposed scene of the crime. Woody had cut a deal. Instead of first-degree murder with the possibility of life in prison, he would plead no contest to manslaughter and get seven years and four months. In exchange, he implicated Carson and the Pop N Cork brothers.

He testified that Carson had asked him and Bobby Athwal to keep an eye on his junk-cluttered property in Turlock. That he witnessed the brothers fatally attacking Korey Kauffman there. That he buried the body in the dirt next to their liquor store, and later unearthed it and dumped it in Stanislaus National Forest.

The government cellphone expert was on the stand for weeks. Jim Cook, who had made nearly $400,000 for his work, claimed that on the night Kauffman supposedly vanished from Carson’s property, cell tower records put the brothers’ phones in that area, not at the Pop N Cork down the block, where they claimed to have been.

Cook admitted he had done his mapping with a protractor and his naked eye, a methodology that seemed to leave Judge Zuniga in disbelief. After sharp challenges from the defense, Cook tried Google Earth.

The new results indicated that Carson’s property fell outside the range where the Pop N Cork brothers were shown to be on the crucial night. The defense trumpeted this revelation, but the D.A. called it flawed and stuck by the original protractor-and-eyeball results.

Carson, at 64, was in physical agony. In court he stood against the wall, his head on his forearm, one hand on his lower back. Sometimes he nodded off. His kidneys had failed, and he was up early for dialysis at the strip mall by Walmart.

In May 2019, with the trial in its 16th month, his dialysis port became infected and nearly killed him. He got a new port and heavy antibiotics, and an outlook whose fatalism had deepened.

“We’re devastated,” Carson said. “They have drained us financially. They’ve drained us emotionally. It’s hard on my marriage. It’s ruined my career.”

Often he thought of his father, his best friend, who had died of cancer just as the investigation had begun. If there was anything good in any of this, Carson said, it was that he hadn’t had to live to see this.

Risen from his deathbed, Carson was back in court representing clients when he wasn’t on trial. He lumbered between courtrooms with his cane and black leather bag, in a black suit he insisted on always wearing until he was acquitted, the jacket shiny in places from overwear.

He asked judges for continuances. They were accommodating. They granted them. “I have the most well-established, unassailable excuse in the whole courthouse,” Carson said.

Carson’s secretary, Felisha Walden, would find him standing on the back patio of his office, drinking a soda in the heat. He had never forgotten the chill of the jail cell, and so now, even on boiling summer days, he refused to turn the air conditioner up, and he took every chance to absorb some sunlight.

“I’m just enjoying it while I can,” Carson would tell her. Juries were fickle. He did not know what they would do. If they convicted, he would die in a cell.

Everyone was exhausted. By the summer of 2019, it had become the second-longest murder trial in the history of the California criminal courts, second only to the Hillside Strangler case. If the long-suffering jurors gave up, there would be a mistrial, which Carson regarded as tantamount to a death sentence. The state could start all over with Witness No. 1, but he could not survive it.

As the trial neared its conclusion, Bobby Athwal would sit in his car watching a music video featuring Sikh horsemen riding into battle. He did this “to make sure I walk OK” in the courthouse halls. The video made him feel connected to a history of warriors who’d faced death unflinchingly. He said, “This is another war.”

After 17 months, stunning verdicts

After a three-year investigation costing untold millions of dollars, after more than 100 prosecutions witnesses, after an 18-month preliminary hearing and a 17-month trial, prosecutor Ferreira stood before jurors making her closing argument and said this: “You might not get a bunch of hard evidence in this case.”

The defense characterized the government theory as a crazy quilt of bad inferences, perjured testimony and junk science, stitched together in a vengeful bid to destroy a criminal defense attorney whose only crime was doing his job too well. The defense portrayed Woody as another victim of an overzealous D.A., a cornered, helpless man who tailored his account to the government’s demands.

The jury was impossible to read, but an alternate named Eric Julien — who sat through the whole case only to be dismissed — had leaned toward conviction. The accounts of Carson making threats had troubled him. So had the fate of Bobby Athwal’s Chevrolet Silverado; he bought the prosecutor‘s theory that it had been deliberately burned to conceal evidence of Kauffman’s remains.

The jury got the case on Wednesday, June 26, 2019, and on Friday there were verdicts. Frank Carson: not guilty. Baljit Athwal: not guilty. Daljit Atwal: not guilty.

Carson’s head was down, and he was weeping. “Murderer!” yelled one of Korey Kauffman’s relatives.

Ferreira said the verdicts stunned her and investigator Kirk Bunch. More than one courtroom observer saw shock on Judge Zuniga’s face as well. It was as if she had presided over a different trial than the jury had seen.

Carson had fantasized about excoriating the judge and demanding an apology, then thought better of it. “My motto is, ‘Thank God that juries are smarter than judges,'” Carson said. He left the courthouse with his arm around his mother.

Back to work, badly diminished

He turned 65 the day after his acquittal, and returned to a pitiless schedule. Dialysis at 4:30 a.m. three times a week, then off to the office or courthouse. He was on a transplant list for a new kidney.

His attorney, Percy Martinez, opened his back patio for an acquittal party that fall. Amid the exultant lawyers and friends, Carson mostly sat quietly. He spoke briefly to two of the jurors who had acquitted them, his voice cracking as he thanked them.

One of them was a 57-year-old Xerox operator named Carrie Agundez. She said many government witnesses, deep in drugs and criminality, had not been believable. She said prosecutors ignored the real suspects.

"They were after one person, Mr. Carson," Agundez said. "It was a witch hunt after Mr. Carson. Myself, I don't think they had anything on Mr. Carson."

Carson and his wife and stepdaughter were suing the district attorney for wrongful prosecution, but he feared he would not live to see it get to court. The Pop N Cork brothers were suing too. So were the California Highway Patrol officers charged in the case. Charges were dropped or resulted in acquittals against all of them. Apart from Woody, the marathon case resulted in no convictions.

“I’ve walked to hell and back now,” Carson said. “I’ve walked through death.”

He was explaining why he shouldn’t be nervous, when he went to trial again as an attorney. But he said he was “petrified.” He didn’t know how people would look at him. Some would always see him as the attorney who somehow got away with murder.

There he stood before a jury in June 2020, the former giant of the courthouse now a hunched and diminished figure, his voice weak, his energy ebbing.

He was arguing self-defense on behalf of a client charged in a stabbing, explaining that one of the witnesses could not be trusted. And so he talked about the PayDay candy bar he bought in Monroe, La., only to find it corrupted by a single maggot.

The jury would convict, but the judge reduced the charge from murder to manslaughter, so Carson counted it as a win. He had fought for five years to stand before a jury, to tell his favorite story one more time.

“When I wanted to eat that PayDay, I didn’t,” Carson told jurors. “I threw the whole thing out. You don’t want that ticklish feeling.”

Two months later, at dialysis, his heart quit. He died on Aug. 11, 2020, about 14 months after his acquittal. He was 66.

“They killed my husband,” his widow would say, and would amend her wrongful-prosecution lawsuit to include wrongful death, on the belief that Carson’s legal ordeal — and his time in jail — had fatally wrecked his health.

At the funeral outside Modesto, Percy Martinez wept and called him a once-in-a-generation lawyer. He said Carson could have walked, if he’d been willing to deal, if he’d given them some kind of win.

Bobby Athwal and his brother Dee were there. So was former highway patrolman Walter Wells, his legs planted shoulder-width, his hands clasped before him. It was the formal posture he had assumed at dozens of cop funerals, when he’d been one himself. He had lost his badge, his home, and his life savings. Now he stood bolt-straight at the graveside of the scourge of local cops, who had offered to surrender his own life for his.

Micah Dizney, the former outlaw who credited Carson with saving his life, said that in a lifetime of exposure to tough characters, in prison and out, he had met only one, Carson, who had embodied the phrase “Better to die on your feet than live on your knees.” He stayed until others drifted away, to shovel dirt on his friend’s grave.

Prosecutors: Our case was strong

“They got away with murder,” prosecutor Marlisa Ferreira said.

If she and her boss, Birgit Fladager, have any regrets about the prosecution, they are not about to share them. With all the lawsuits pending, they have strong incentive not to admit error.

They insist they had a strong case. They just couldn’t get a jury to convict.

The case lacked physical evidence linking Carson to the crime, but Ferreira has incorporated this into her theory of his guilt. As an experienced defense attorney, of course he would know how not to leave a trace.

“I’m not shocked at all that he would get away with murder,” Ferreira said. “Because if anyone could, he would.”

Her certainty extends to Robert Woody’s involvement in the crime. She knows he was there. How else would he have led police to the site where the bones had been found, deep in Stanislaus National Forest? She was there to watch it.

"Goose bumps,” she said.

Yes, Woody lied repeatedly, but when he walked into court and swore an oath, she believes he was honest.

“When he took the stand, absolutely,” Ferreira said. “No doubt in my mind.”

The last word: Robert Woody

“Make-believe. Stories they wanted to hear.”

This is Robert Woody, a free man now, his time served on his sentence. He is describing his testimony during State vs. Carson et al. He says he made it up.

He was locked up for empty boasting about a murder he had nothing to do with, he says, but the details of his meth-fueled “confession” — the chopped body, the yanked teeth, the devouring pigs — showed no actual knowledge of the condition of Kauffman’s remains.

“They bit the bait!” Woody said incredulously. “They jumped on it like fools!”

Yet when he tried to tell cops the truth, he says, they just called him a liar. They charged him with first-degree murder. They threatened him with life in prison; they threatened him with the death penalty. He had to lie, he says, concocting a story that would help the government’s case and minimize his own time behind bars.

“I wanted to get back to my family.”

He had studied the cops’ body language. He looked for their “feedback” in response to his guesses. They threw out details; he wove them into his account. “Almost like when someone reads you a story,” he said. “They give you a test on it.”

What about the trip to the mountains? How had he led them to the site where the body had been found, if he hadn’t dumped it there?

“They took me out there,” Woody said. He had relied on the marker flags, stuck in the ground. “I seen what they were looking for, so I pointed it out.”

He’s home now, in the little house down the block from the Pop N Cork. He is a small, stoutly built man with a thick beard and wary, vivid blue eyes. He wears tan work boots. He is happy to be working again. Jail was hell.

Woody had been unable to lead police to a single piece of irrefutable physical evidence showing his involvement in the crime. He seems to find it almost unbelievable that the sworn custodians of the law — police, prosecutors, judges — actually seemed to have taken him seriously.

Didn’t they see the obvious discrepancy between the condition of the bones and how he’d described them? Weren’t they listening, when he repeatedly said he was willing to lie if it would set him free?

He shakes his head at the absurdity of it. As if to underscore his unreliability, Woody says he might be making this up, too.

“Nobody knows,” said the government’s star witness in California’s second-longest murder trial. “I could be pulling your leg right now.”

Read more from this series:

Listen to the podcast:

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.