A 1787 federal law forbade slavery in Ohio, but African Americans here still faced abuses

The history of African-Americans in Columbus and central Ohio is a long and complex story. African-American people have been living in the land north and west of the Ohio River called the Ohio Country for the last several hundred years. Some were runaway slaves who were accepted and became part of the Native American groups living in Ohio. The African American population was small – but then the Native population was small as well and soon to be overwhelmed by newcomers from the East.

The Northwest Ordinance of 1787 forever forbade slavery north and west of the Ohio River. So the former slaves who came north with Lucas Sullivant in 1797 to found the frontier settlement of Franklinton were now the paid servants and employees of their former masters. This did not, however, mean that the former slaves were free of restraints.

Black Laws passed in the early history of Ohio denied the right to vote to free African Americans, limited a number of political rights and imposed segregation in schools and other public facilities.

Early laws also mandated that runaway slaves captured in Ohio by agents of their owners or other bounty hunters, had to be returned to slavery. An early history of Ohio explained the response to these laws.

“Early in the history of Ohio, it became very evident that the section of the Constitution of the United States and supplementary acts of Congress, providing for the reclamation and surrender of fugitive slaves were odious to many persons in this free state, and were really only favored by only a small and diminishing minority … Columbus, being within easy reach of the river border, it was one of the way stations on the ‘Underground Railroad’ from thence to Canada, and became the scene of many of these contentions.”

Many of these cases ended up in state and local courts. In some cases, the runaways were reluctantly returned to their masters. Other cases were more complicated. Perhaps the most famous of these in Columbus was the case of Jerry Finney. A long-time resident of Columbus, Finney was an established worker in local commerce and well-known by the residents of the city. Captured by agents of his former owner in 1846, Finney’s return was opposed by local authorities. Finally returned to slavery, Finney was freed when a local collection of money purchased his freedom and returned him to Columbus.

Other local free African Americans found similar answers to similar problems as reported in an early history.

“Of Robert Napper, a colored citizen of Columbus, we have the following curious account. He was born a slave, the property of a Mr. Davis, residing near Staunton, Virginia. At the age of thirty-four, Napper, then married and the father of five children, proposed to John Brandenburg, a merchant of Staunton, to buy him and hire him out, a certain proportion of his wages to be applied to his purchase.”

“Brandenburg bought him for one thousand dollars, and hired him out for four years, during which time he earned his freedom and received his emancipation papers. He then came to Columbus and after the lapse of one year was able to and did buy his wife for $656. In July, 1860, he bought his youngest boy, Cornelius, aged eleven, who was forwarded to him by Adams Express. From his master Cornelius received, on July 4, a gift of twenty-five cents, of which he spent en route ten cents; the remainder he handed to his father before he left the express office, with the request that it be applied to the purchase of his little brother still in slavery.”

“Napper hoped at that time to purchase the rest of his family, comprising two girls aged fifteen and eighteen, and a boy aged thirteen. He little foresaw the great events, then near at hand, [the American Civil War], by which human slavery was about to be extinguished forever in the American Union.”

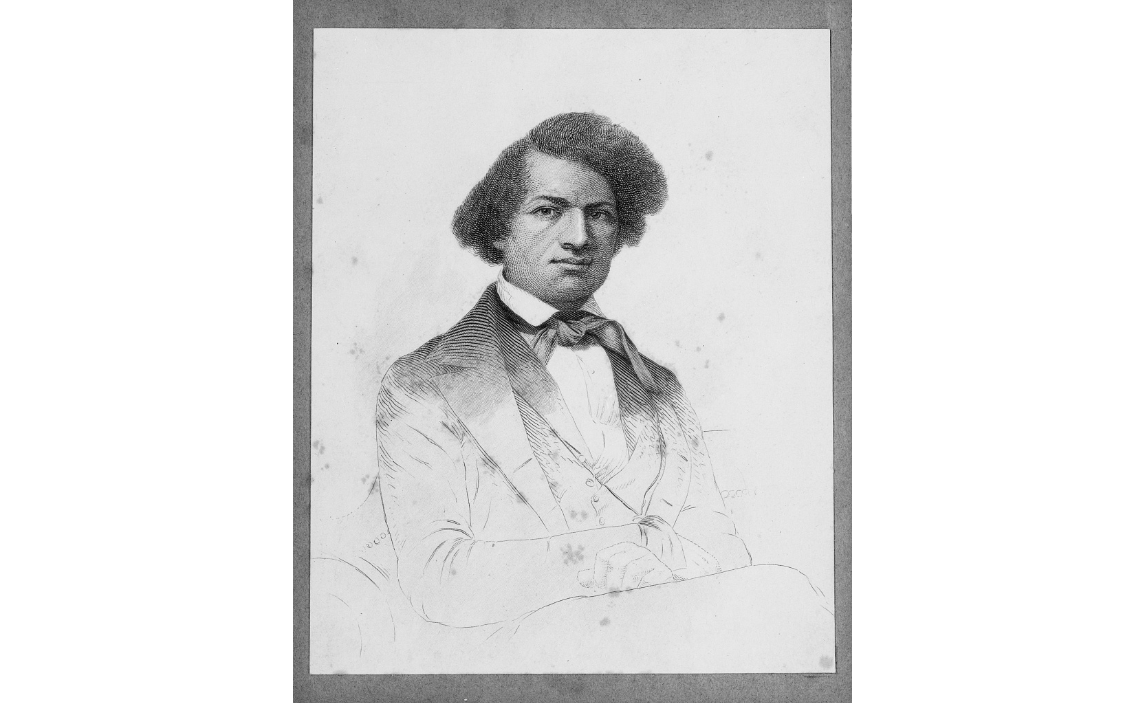

Other people were more direct in their approach as an older history reported:“On July 16, 1850, Frederick Douglas [sic], the distinguished colored orator, paid to the Ohio Stage Company, the sum of three dollars, which was the regular stage fare, for his passage from Columbus to Zanesville. When the stage called for him in its rounds for passengers, he took a seat inside with a lady who had delayed her journey for a day or two for the benefit his protection, but on their arrival at the stage office, Douglas was ordered out of the coach by Hooker the agent.

"Being in poor health and disinclined to contend with the agent, Mr. Douglas got out and was then ordered to tale a seat on top of the stage. He declined to do that and demanded his money back. This being declined he brought a lawsuit to recover it. Joshua Giddings was his attorney. The case did not come to trial but was settled, the company paying the plaintiff thirteen dollars and liquidating the costs of the suit.”

Frederick Douglass returned to Ohio many more times.

Local historian and author Ed Lentz writes this " As It Were" column for The Columbus Dispatch.

This article originally appeared on The Columbus Dispatch: Lentz: 1787 law forbade slavery in Ohio, but Blacks still faced abuses