18 Texas species supported by the Endangered Species Act over 50 years

The daunting sight of a grizzly bear traversing the expansive Great Plains, with its massive form contrasting against the sweeping landscapes, might evoke a profound sense of contemplation.

The species — once a vital part of the Great Plains ecosystem, even into northwest Texas — has vanished from a large part of its historical range, leaving only echoes of its presence.

But a different narrative unfolds for the species' remaining population, greatly attributed to the Endangered Species Act. Enacted 50 years ago on Dec. 28, 1973, this legislation has played a pivotal role in preserving and protecting the remaining population of grizzlies, one of the planet's most charismatic predators.

Signed by Former President Richard Nixon — with a 355-4 vote in the House of Representatives and unanimous vote in the Senate — the Endangered Species Act serves as a safeguard for plants and animals facing the threat of extinction.

The list of more than 1,400 endangered and threatened species is updated each year as federal scientists determine when protections are necessary. Once a species is added to the list, the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service (FWS) or, for most marine species, the National Marine Fisheries Service, is required to formulate a recovery plan, often in partnership with their state counterparts and native tribes and landowners.

As it enters its 50th year, the Endangered Species Act has been instrumental in saving hundreds of species on the brink of extinction. Without this legislation, the nation may be absent of gray wolves and black-footed ferrets, the seas devoid of hawksbill sea turtles, and the bald eagle — the national symbol — reduced to a mere relic of the past.

Albeit often characterized as ineffective in some parts of the political sphere, which has perpetuated long-standing criticism of the Endangered Species Act’s impact on industry and private property rights, wildlife conservation experts say the legislation has, to date, halted the extinction of 99% of the species under its protection.

To date, 64 species have been successfully delisted due in part to recovery efforts compared to 32 that have become extinct, USA TODAY reported on the anniversary of the legislation last month. Additionally, the 2019 PeerJ study cites a proved list of 291 species for which the Endangered Species Act has effectively slowed further loss.

“For most of its life, it's been a very bipartisan issue, so it's a success story for both parties, and it's also mostly been a success story from a conservation perspective,” said Gad Perry, a professor in natural resource management and conservation biologist at Texas Tech University. “That's because most of the species that have been put on it have survived, even though by the time they're added, they're usually in dire straits. I think it deserves tremendous accolades."

In Texas, more than 100 species receive federal protections under the Endangered Species Act — ranging from the more popular Mexican-long nosed bat and golden-cheeked warbler to the lesser-known bracted twistflower and Comanche Springs pupfish. Some species have experienced robust recoveries, while others, such as the San Marcos gambusia, officially declared extinct in October, have not fared as well.

Reporter's Note: The descriptions of species are based on species directories from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

Amphibians and fish

In the subterranean depths of the Lone Star State, the Texas blind salamander lives in total darkness. With vacant eye sockets, its vision reduced to two inconspicuous black dots beneath the skin, this species navigates the water-filled caves of the Edwards Aquifer in Central Texas. The peculiar creature was deemed endangered by federal scientists back in 1967, years before the legislation even existed, and has remained on it since.

The Houston toad, measuring up to 3.5 inches, sports hues ranging from light brown to gray or even purplish gray, occasionally adorned with patches of green. Its survival is intricately woven into the fabric of Central Texas, relying on the embrace of loose, deep sands that cradle the Loblolly pine forests or the mixed post oak-woodland savannah. In 1970, federal scientists recognized its dire need for help.

Along the sinuous course of the Rio Grande and Pecos rivers, the Rio Grande silvery minnow tells a tale of dwindling waters and rising temperatures. Once spanning vast stretches of these majestic waterways, this 4.6-inch fish now occupies a mere 7% of its historic range, prompting its listing under the Endangered Species Act in 1994. They are the last of five species with similar life histories as pelagic spawners that still exist in the Rio Grande.

In the arid prairie streams of the Brazos River system, the smalleye shiner is a testament to the struggle against encroaching human intervention. Historically coursing through much of the main river, the shiner's fate took a downturn with the construction of reservoirs in the 1940s. Now confined to the upper reaches of the Brazos basin, upstream of Possum Kingdom Lake, this pale olive minnow found itself on the endangered list in 2014.

Invertebrate and reptiles

Endemic to the Austin region, the Tooth Cave spider, a diminutive arachnid of a mere 0.1 inches, intricately weaves webs from floor to ceiling throughout its limestone cave habitat in Central Texas. With a population numbering fewer than 250, this tiny spinner earned its spot on the Endangered Species Act back in 1988.

Inhabiting the air-filled cavities of two Texas springs, the Comal Springs dryopid beetle — distinguished by their reddish-brown bodies and non-functioning eyes — presents a curious paradox. These creatures, residing in an aquatic environment, are incapable of swimming. The tiny insects have also further demonstrated tenacity by surviving a drought in 1956, which temporarily halted the flow of the Comal Springs, which they depend upon for survival. Population size currently unknown, the species was listed as endangered in 1997.

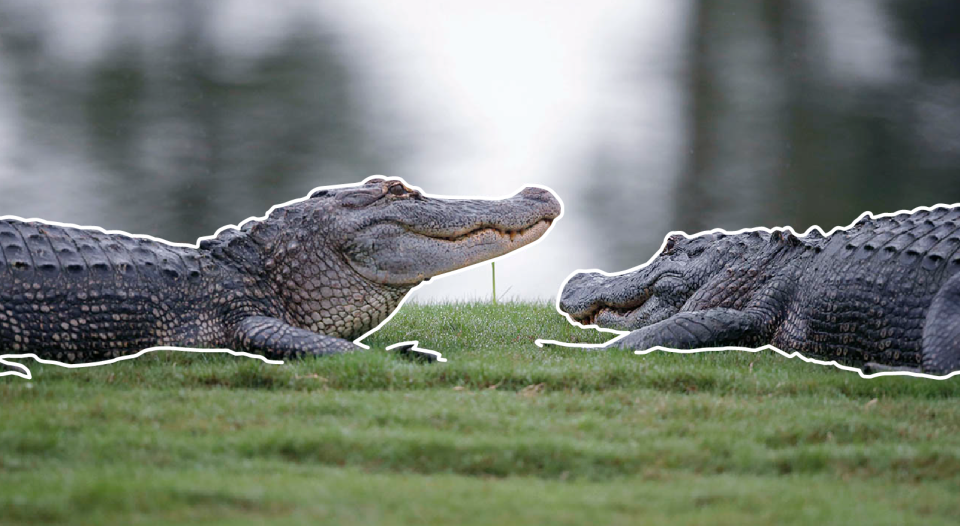

In the vast expanse from the Floridian Everglades to the Louisiana swamps and along the Gulf Coast, the American alligator secured federal protections in 1967. A mere two decades later, it triumphantly emerged from the list. Resurrected from the brink of extinction, today, over a million of these resilient reptiles flourish in their natural habitats.

As the largest living turtle species, the leatherback sea turtle stands out not only for its size but also for being the only sea turtle without scales and a hard shell. With nests gracing tropical and subtropical beaches, it boasts the broadest global distribution among reptiles. Over the past three generations, its population has dwindled by almost half, facing the imminent threats of bycatch and hunting. In 1970, the species was labeled as endangered under the Endangered Species Conservation Act, a precursor to the Endangered Species Act.

Birds

Exclusive to the coastal prairies of Texas, the Attwater's prairie-chicken is a charismatic bird, standing at a modest height of less than two feet. In the dance of mating season, males craft a distinctive "booming" sound —audible from half a mile away. This enchanting species found itself on the endangered list in 1967, and today, has seen its highest population since the early 1990s.

In the expansive realm of the southern Great Plains, the lesser prairie-chicken faces its biggest challenge in habitat loss as a result of industry development. After a prolonged struggle spanning several decades, the species finally secured its place on the endangered list in October, marking a significant victory for the species.

The Mexican spotted owl, a notable presence as one of North America's largest owls, stands out with its distinctive dark eyes, a rarity among its nocturnal counterparts. In Texas, this creature inhabits only the mountains of the Davis and Guadalupe Mountains in West Texas. The species was deemed threatened in 1993.

As the tallest bird in North America, the whooping crane once soared in historic numbers of about 10,000 from Canada to Mexico. Today, the entire population, numbering around 800, traces its lineage to the all-time low population of 15 whooping cranes wintering at Aransas National Wildlife Refuge in Austwell, Texas, back in 1941, according to the USFWS. It was first declared endangered in 1967.

Flora

Texas wild rice, a submergent aquatic perennial grass boasting leaves stretching from 3 to 6.5 feet, holds a unique presence in the San Marcos River. As a source for the also endangered fountain darter fish, survival for Texas wild rice hinges on the consistent flow of the spring. It was listed under the Endangered Species Act in 1978.

The prostrate milkweed, a rare flowering plant, acts as a crucial food source for various pollinator species, such as bees and butterflies. Found in only 24 populations spanning southern Texas and northeastern Mexico, this species was officially listed under the Endangered Species Act in March.

Flourishing along the salt marshes of spring systems in the desert wetland ciénegas of West Texas, Utah and New Mexico, the Pecos sunflower — also dubbed the puzzle or paradox sunflower — is distinguished by its lance-shaped leaves and captivating flower heads. The species was listed threatened in 1973.

Known only in East Teas, the Texas trailing phlox is a fire-tolerant flower in the state's Longleaf Pine region. Unique for both its geography and durability, the beloved flower species was listed as endangered in 1991.

Mammals

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service lists six mammal species with spatial current range believed to or known to occur in Texas. Among them, three no longer have populations within the state but continue to prevail elsewhere: the Gulf Coast jaguarundi, which once roamed the dense shrublands of the Rio Grande Valley; the Mexican wolf, previously seen in the Big Bend National Park; and the West Indian manatee.

Among those that are still here: the ocelot, a small cat with an estimated population in southern Texas of between 80 and 120 total, the Mexican-nosed bat and the northern long-eared bat.

This article originally appeared on Lubbock Avalanche-Journal: 18 Texas species supported by Endangered Species Act marking 50 years