In the 1930s, bank robberies were a craze. This one out of Cincinnati may take the cake.

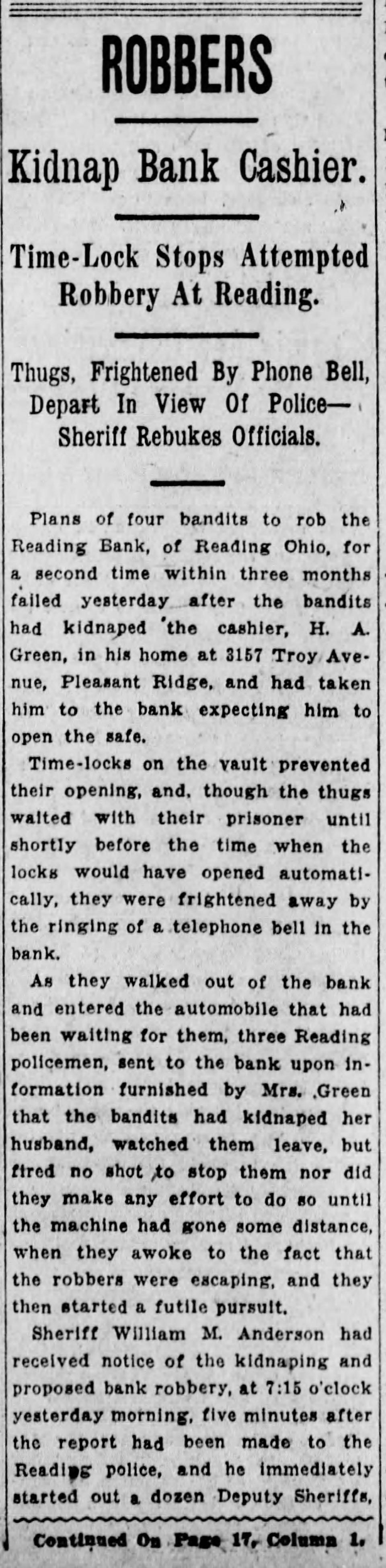

Perusing old Enquirer pages on Newspapers.com, a headline from June 22, 1930, caught my eye: “Robbers Kidnap Bank Cashier. – Time-Lock Stops Attempted Robbery At Reading.”

So I followed the case through the newspaper coverage in The Enquirer and the Cincinnati Post.

It played out like a James Cagney gangster movie.

In the 1930s, bank robberies were something of a craze. Real-life bandits John Dillinger and Bonnie and Clyde captured the public’s attention with daring hold-ups and violent shootouts.

For me, the story began with the news accounts of that robbery attempt.

Queen City Crime: George Remus, the wife-killing 'King of Bootleggers'

Historic crime: Cincinnati painting heist of 1973: A $200K ransom, a double-cross, heck of a twist ending

Cashier kidnapped by bandits waiting for a vault time lock

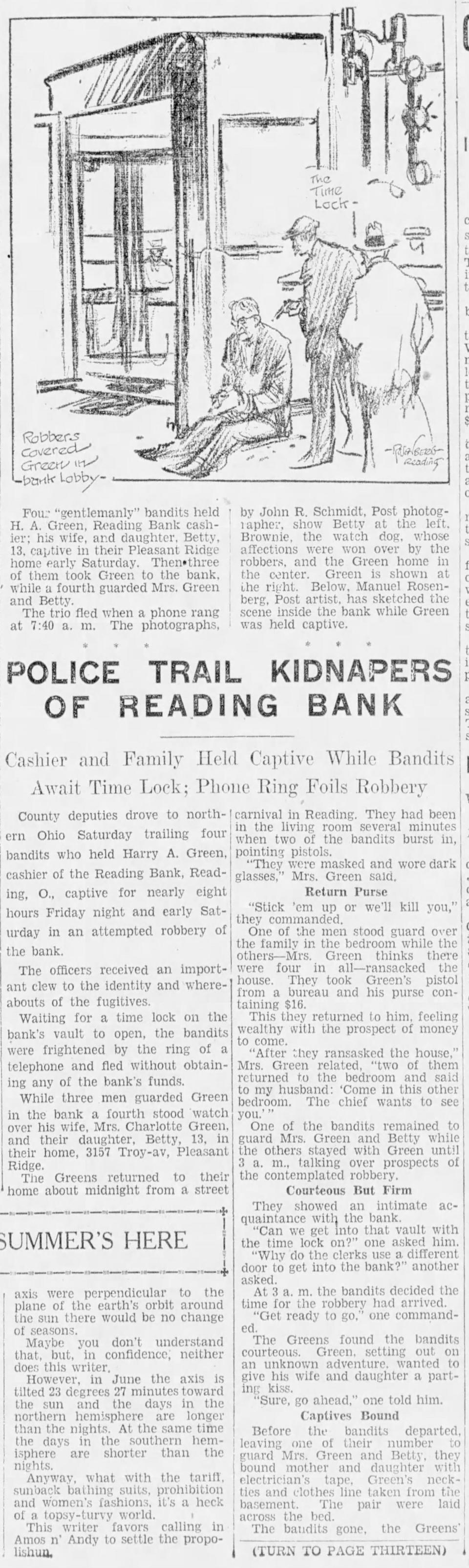

For several hours in the early morning of Saturday, June 21, 1930, Harry A. Green, a cashier at the Reading Bank in Reading, Ohio, his wife and his daughter, Betty, 13, were held captive by a gang of bank robbers.

Just after midnight, four bandits brandishing pistols broke into the Green home in Pleasant Ridge and demanded, “Stick ’em up or we’ll kill you.” The men wore handkerchief masks and dark glasses. Two were well-dressed, one in a Panama hat.

They ransacked the house, taking Green’s pistol and $16 (just under $300 today).

At 3 a.m., three of the men took Green to the bank, first allowing him to give his wife and daughter a parting kiss.

One bandit stayed behind at the house to guard the family that was bound in electrician’s tape, neckties and a clothesline. He kept checking his watch, then left the house about 6 a.m. Within an hour, Mrs. Green managed to free herself and called the bank president.

Meanwhile, the other robbers, with Green tied up, waited in the bank on Benson Street for the time lock on the vault to release at 7:55 a.m. But 15 minutes before that deadline, the telephone rang and spooked the bandits, who decided to leave with only Green’s $16.

Alerted by the wife’s alarm, police arrived at the bank right as three men exited the building, hopped into a blue Ford and drove away. The police did not fire on the robbers, thinking that in those nice clothes they might have been customers.

They had robbed the bank before

Green had recognized one man when his mask slipped as someone from the gang that had held up the same bank on April 4 of that year, escaping that time with $8,418, which would be $152,000 today. (That same day in April, robbers hit a Dayton, Ohio, bank for $33,000. It was free-for-all at the banks.)

That morning, Green had been talking to a salesman about a tear-gas apparatus for frustrating hold-ups when suddenly four robbers armed with revolvers and automatic pistols charged into the bank and stuffed the money in a bag.

Frank Gais, a grocer across the street, recognized a robbery was in progress. He grabbed his own revolver and fired at the robbers. A bandit fired back.

“They’re pecking at us; let’s go,” one said.

They hurried into a big car waiting for them. Gais emptied his gun at the escaping car, its occupants firing back at him through the rear window, which had been shot away.

The gang would be wanted for other bank robberies in Mason, Silverton, Hamilton and Amelia between January and June 1930.

‘They all get caught some time’

On July 9, it was reported that Harry Zenz (known as Pete), 21, of Carthage, and Esther Genin, 20, of Elmwood Place, had been picked up.

Zenz was charged with kidnapping, accused of being the bandit who guarded Mrs. Green and her daughter. Authorities thought Genin drove the getaway car, but they ultimately released her, their reasoning unclear.

However, Genin had kept a diary that told of several robberies committed by the gang.

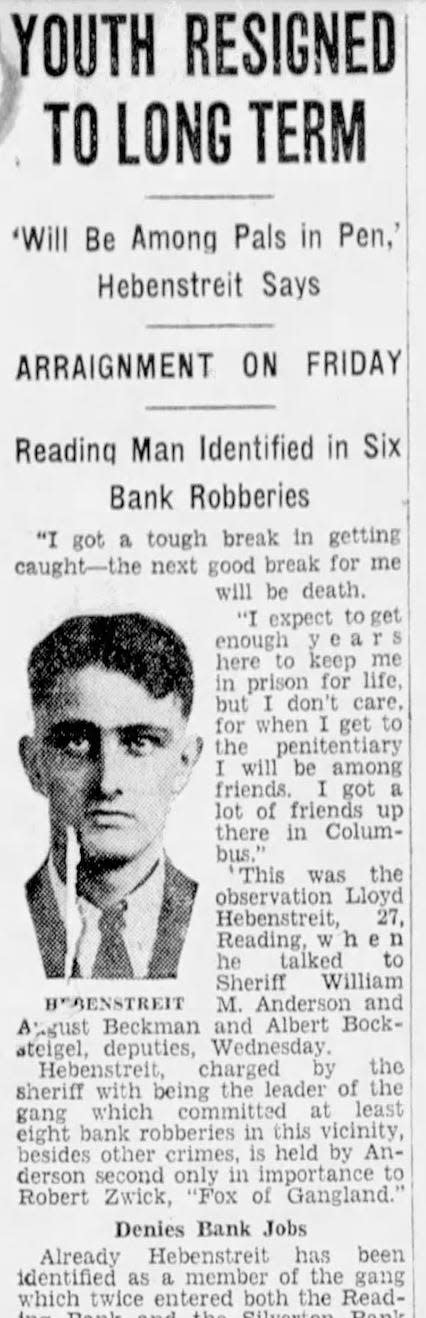

On July 28, the leader of the gang, Lloyd A. Hebenstreit, 27, was arrested in Hamilton. He was identified by witnesses at several of the robberies and was sunk by Genin’s diary.

“I always told her that book would cause trouble,” he said.

“I knew you fellows were after me,” Hebenstreit told the Hamilton County sheriff, as quoted in the Post. “… I knew I would get caught some day – they all get caught some time. Maybe I wouldn’t be in now, if it wasn’t for the break I got in Hamilton.

“Monday, you remember, was hot. I stopped my machine and decided to take a little walk. I took off my coat, first putting my ‘rod’ in the pocket of the machine, and started walking. It was the first time I was without my ‘rod.’

“Then I saw the officers approach me. I turned to run back to get my gun, but they got the drop and I stopped. It was a tough break, for if I had had my gun I would have shot it out with them.”

Hebenstreit was from a well-to-do Reading family. His mother was a stockholder in the Reading Bank he robbed.

Asked why he spurned a good family and home, Hebenstreit said he preferred his “true friends” he met in prison.

“I expect to get enough years here to keep me in prison for life, but I don’t care, for when I get to the penitentiary I will be among friends. I got a lot of friends up there in Columbus,” he said.

Two sentenced to life in prison

Hebenstreit and Zenz were indicted in the robbery and kidnapping. Zenz was released on a $10,000 bond until trial. Hebenstreit tried to saw his way out of the county jail (Zenz was thought to have supplied the saws), and another time planned to smuggle weapons into the jail and “shoot his way out,” but the schemes were foiled.

In May 1931, Hebenstreit and Zenz were convicted under a new law at the time that sentenced life imprisonment for bank robbery. A third robber, Walter Flory, 20, was given mercy because of his young age and sentenced to 20 years in the Mansfield Reformatory.

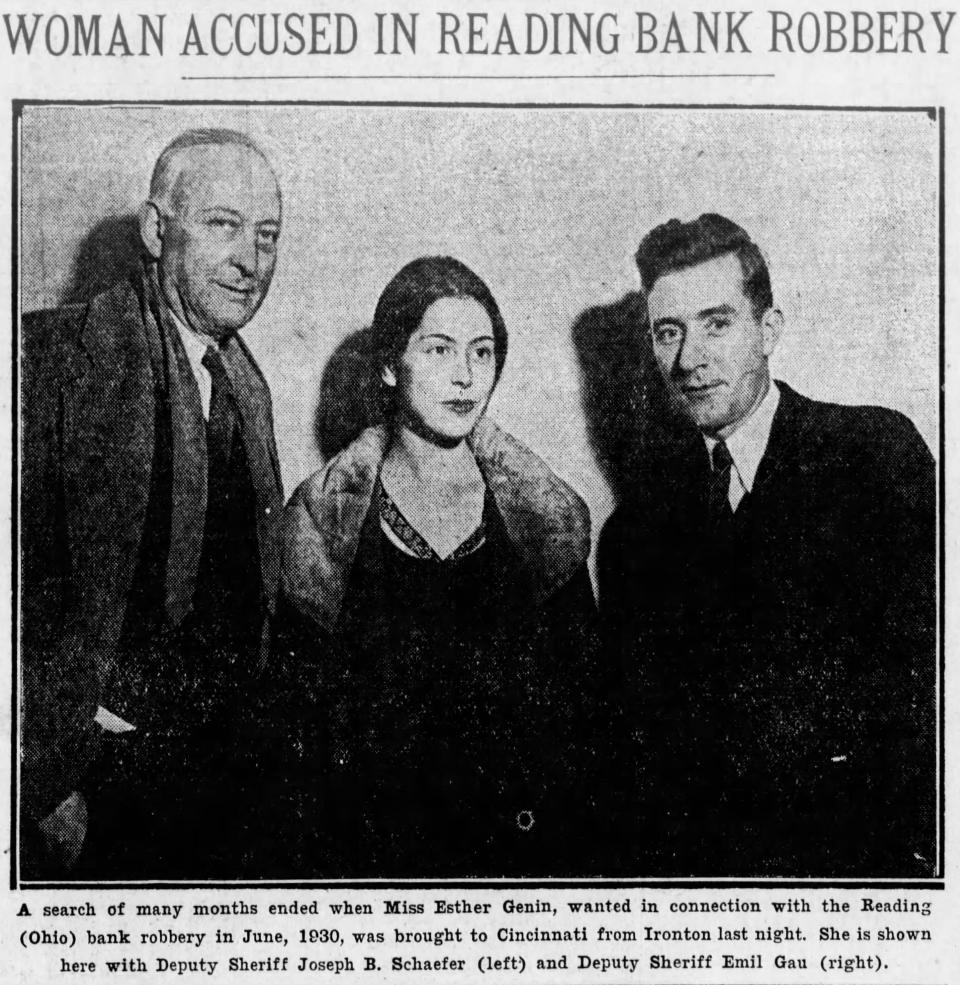

Esther Genin evaded the police for 18 months. She was arrested in Ironton, Ohio, in December 1931, and was the first woman charged with bank robbery in Hamilton County.

Hebenstreit, described as Genin’s “former sweetheart,” wrote a note on a Christmas card to the prosecutor: “If you want to give one the best Christmas present in the world, give it to me and never try Esther, and make a low bond so she can go home for Christmas. John, that kid’s innocent, so help her; don’t prosecute her.”

Charges against her were dropped. She later revealed that she and the other bandit, Zenz, were secretly married in October 1930.

The fate of the bandits

The fourth bandit, Ellis Delks, was never captured. He met his end in a shootout with police in South Bend, Indiana, after killing two patrolmen.

According to the South Bend Tribune, Delks, then known as Donald Murdock, was stopped by Patrolman Delbert Thompson near midnight on May 26, 1933. Delks struggled for the policeman’s gun, shot him five times and ran.

Patrolmen Charles Farkas and Daniel A. Martin spotted Delks, who opened fire on them. Farkas fell dead and Martin was shot in the shoulder, but returned fire with a shotgun until Delks was dead.

Hebenstreit, paroled in 1942, made headlines again in October 1946 when he was dumped in the parking lot of a Reading funeral home suffering from bullet, shotgun and knife wounds. His friends claimed he had been working as a dice dealer in a Northern Kentucky gambling casino, but he was mum about the men who jumped him.

He was killed in an auto accident in 1947.

Zenz escaped from a prison farm in London, Ohio, in 1938, then was convicted of burglary in Texas. His parole was rescinded in 1947 after the prosecutor protested. He was finally released in 1957 and died in 1983.

His death notice read “dear husband of Esther Zenz” (although they had divorced in 1941). In the death listing for Esther Bachman-Zenz (nee Genin) in 1985, she was “beloved wife of the late Harry (Pete) Zenz.” Neither listing mentioned their colorful past.

This article originally appeared on Cincinnati Enquirer: Move over Bonnie and Clyde, this Cincinnati bank robbery drops jaws