In 1942, Camp Amache held 7,500 Japanese Americans prisoner. Survivors want the world to remember

GRANADA, Colo. – Stained with coal dust and sweat, the exhausted families climbed down from the crowded train.

They’d been sleeping in their clothes for four long days, crammed shoulder-to-shoulder in their seats, eating cold sandwiches handed out under the watchful eyes of armed guards. They’d taken their bathroom breaks in the bushes alongside the tracks. They’d baked in the desert and shivered over mountain passes as the rattling train hauled them from their hastily abandoned homes and farms, shops and businesses in California.

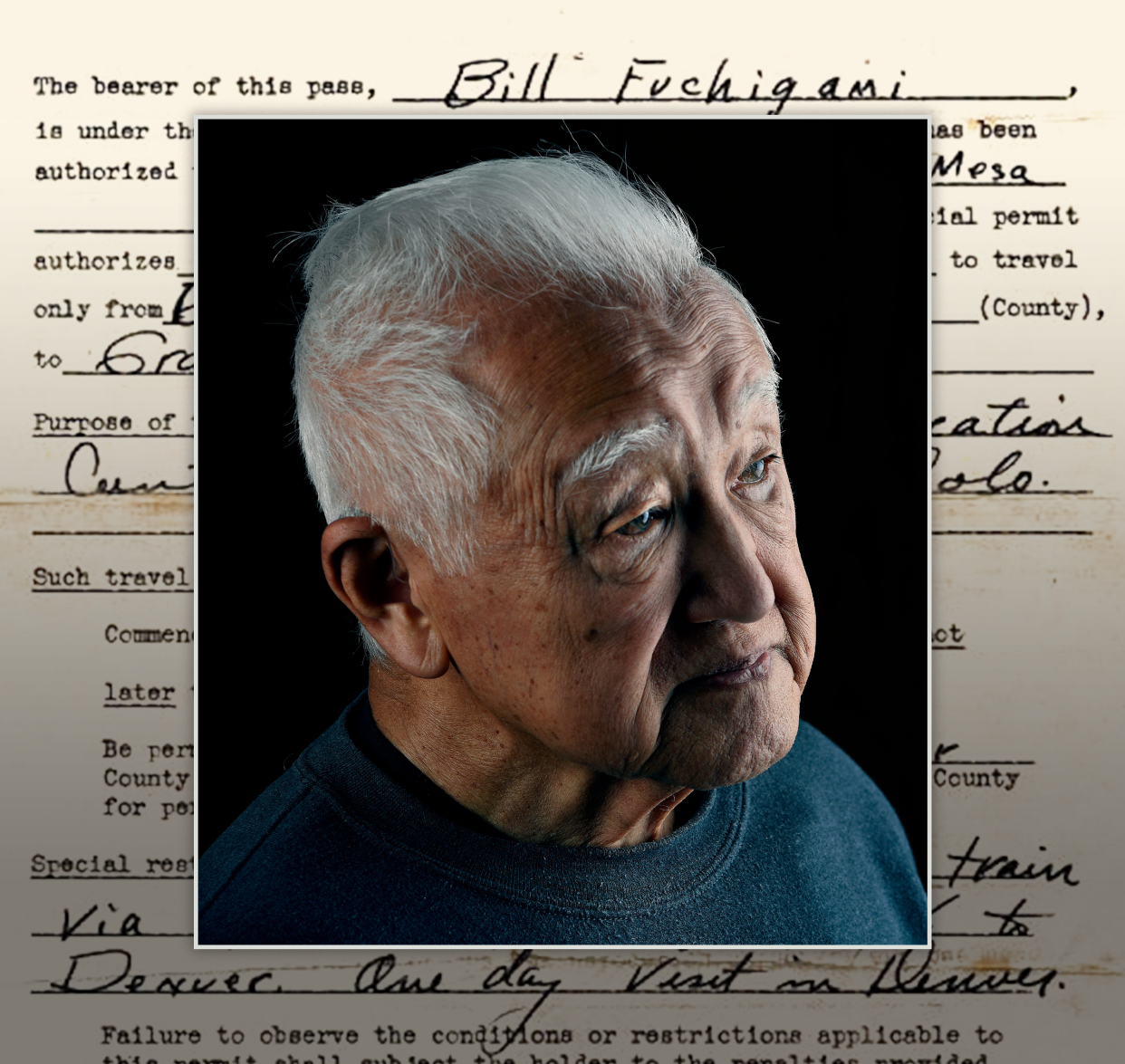

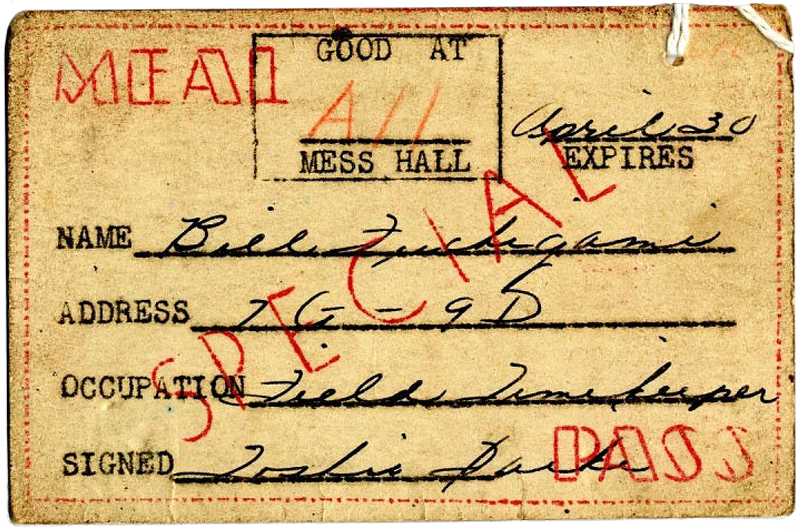

Bob Fuchigami and his siblings clambered out, trying to find their meager belongings. They sought out their parents and familiar faces as soldiers with bayonets on their rifles hustled them onto trucks and buses for the short ride into the barbed-wire perimeter of the Granada Relocation Center. Guard towers loomed. Soldiers with machine guns manned spotlights.

It was September 1942. Fuchigami, his family and thousands of other Japanese Americans in California had been rounded up by the government, detained in horse stables on rodeo grounds for months before being herded onto an eastbound train for Colorado.

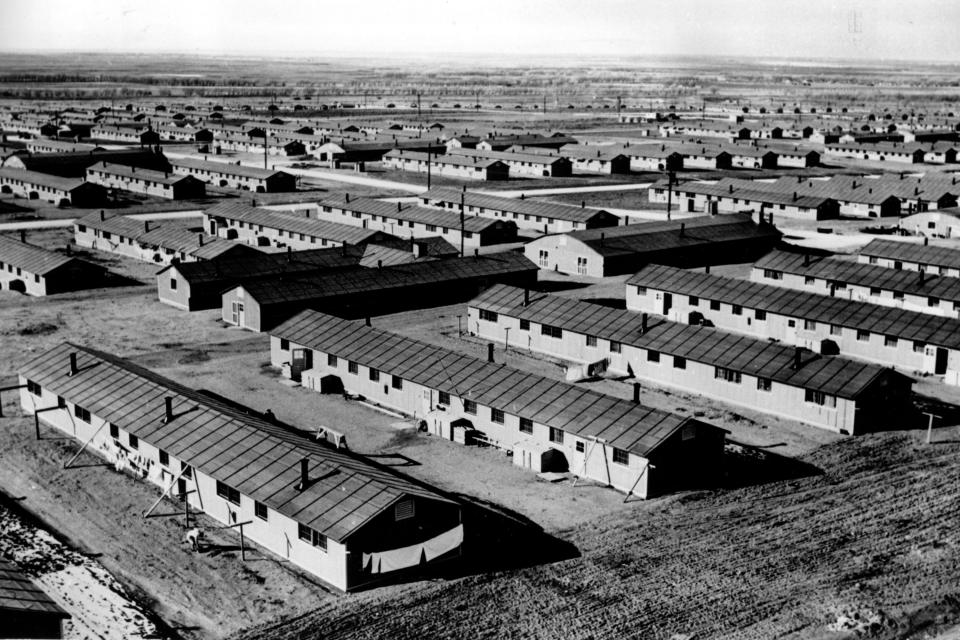

There, in a desolate corner of the state near a town nicknamed “End of the Line,” the federal government had hastily erected a smaller town known informally as Camp Amache where the detainees would live out the remainder of World War II unless they volunteered for the front lines.

Fuchigami was 11. He and his seven siblings were all American citizens by birthright.

It didn't matter.

In the months following the attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941, the U.S. government, buoyed by a century of anti-Asian racism, forced more than 120,000 people of Japanese descent to leave their homes and businesses along the Pacific Coast as WWII raged. First dubbed an "evacuation" and then a "relocation" by the government, it swept up immigrants and citizens alike – fully two-thirds of the people detained in camps during the war were U.S. citizens stripped of their civil rights, never accused of either a crime or collaboration with the Japanese military.

This series explores the unseen, unheard, lost and forgotten stories of America’s people of color.

Now 91, Fuchigami is part of a shrinking generation of Japanese Americans who have kept alive the story of Colorado's Camp Amache and the nine other camps in California, Arizona, Wyoming, Utah and Arkansas. They worry that unless the United States confronts its racist past, it will inevitably repeat some of the mistakes of that era as a new wave of anti-Asian hate festers and right-wing politicians ramp up anti-immigrant rhetoric.

USA TODAY is telling the story of Amache through the accounts of a handful of survivors and descendants, coupled with letters camp detainees wrote and documents they carried that bear witness to this dark moment in U.S. history.

Never Been Told: These stories fill in the history of people of color

Jackson Giles: In 1902, a postal worker challenged Jim Crow Alabama for his right to vote

“After more than one year in the center, I am convinced that only a very few Caucasians will ever understand the pain of evacuation,” detainee Yuri Domoto Tsukada wrote in an unsent letter to a friend dated July 4, 1943.

While some students learn about the Japanese American detention camps, few learn the details or explore the parallels between places like Amache and the German-run concentration camps where millions of Jewish people were locked up and killed during the war.

Even fewer learn of the camps’ lasting legacies. There were the billions of dollars in income and property taken from the detainees and restored, if only symbolically, by reparations in 1988. There were also the heroic Japanese American soldiers who helped liberate Europe, including those in concentration camps; and the drive for success instilled in many detainees determined to prove themselves worthy Americans.

Congress is poised to make Amache a national historic site run by the National Park Service, with backers hopeful that formal recognition will help tell the story of both the detention center and the people forced to live there.

‘Water isn’t suitable for drinking’

Even as a child, Fuchigami felt the festering racism that banned him and his family from public swimming pools and golf courses and saw the "J--s must go" signs. He remembers the newspapers editorializing against Asian immigrants and their American children, and he sees uncomfortable parallels today.

"While all of the children were loyal, patriotic U.S. citizens, we learned our 'place' as part of our community," he said. "We recited the Pledge of Allegiance every day at school but learned that liberty and justice for all did not include us."

Living a few buildings away at Amache was Henry Fujita, who was 34 when forced by the government to give up his job as a vacuum salesman and abandon the family farm.

Fujita was already familiar with anti-Japanese racism: In 1928, the local chapter of the American Legion complained his parents were violating California’s alien land law by putting their farm in their kids' names. The California Supreme Court eventually ruled that Henry, then 19, and his siblings were entitled to the same rights as other American-born people, allowing them to keep their farm.

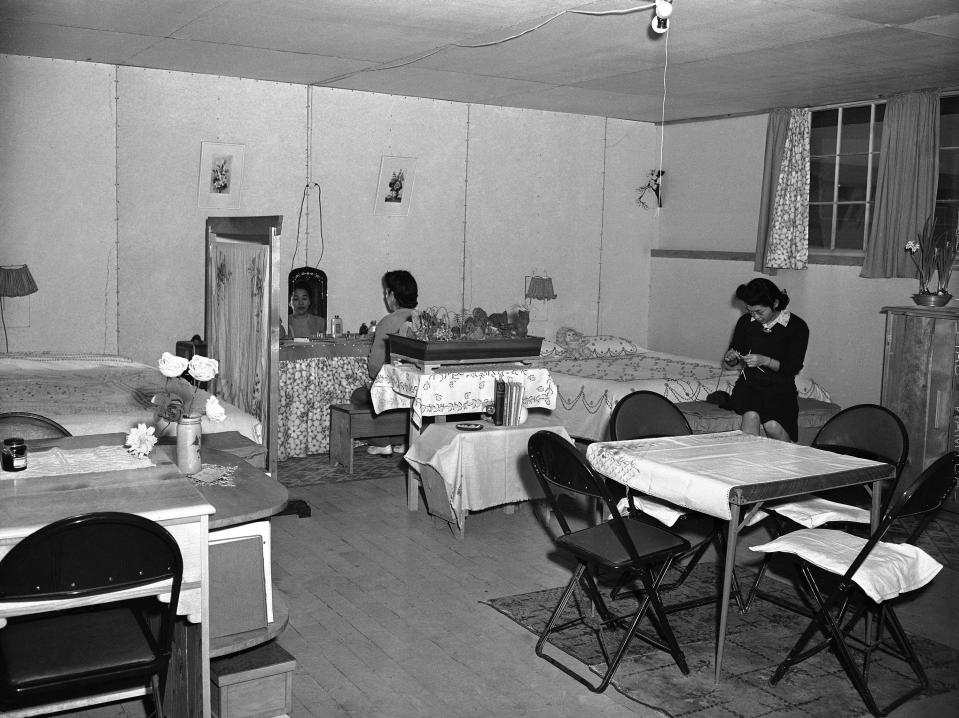

In a typewritten letter to friends that he dictated to his wife, Fujita described the conditions upon arrival at Amache, from the hastily erected brick-floored barracks they lived in, to the military police at the gate. He also described the walls, built with a material that likely contained a mix of sugar cane and asbestos, covered with tar paper. The War Relocation Authority deliberately built the camps far from cities, picking remote areas near train tracks.

"At first, the water was always running out and we’d have to wait for the tank to fill up again. The water isn’t suitable for drinking yet because the well casing and pipes still have too much oil on the insides," he wrote. "...When the wind blows we have a sandstorm. It’s really bad. The sand sifts in from all over and if we're caught outside in it we're nearly blinded by the flying sand."

‘Fabulous’ Lena Richard: In Jim Crow times, a Black woman chef from New Orleans built a food empire

A complicated love story: Author Carlos Bulosan’s critique of America gave Filipino migrants a voice

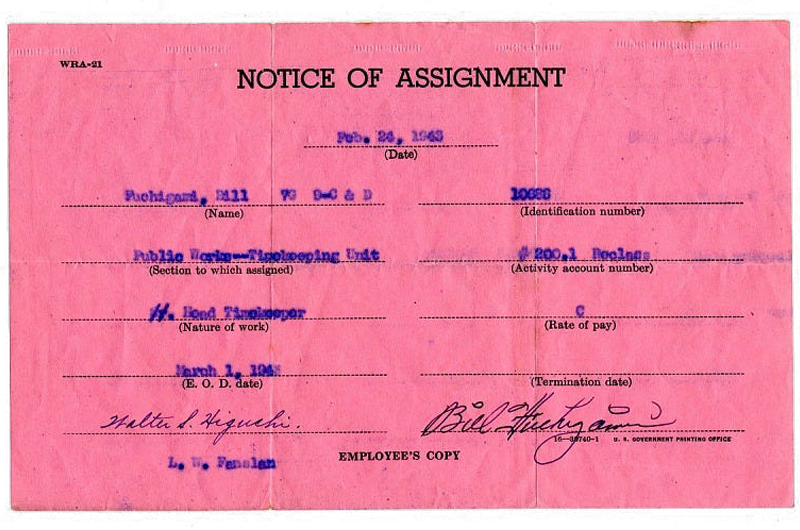

Fuchigami remembers his brothers picking up bent nails discarded by construction workers and scrounging for leftover lumber to build crude chairs, a table and a divider so their parents had a modicum of privacy from their three daughters and five sons. Their address was Block 7G- 9C and 9D. Because there were so many of them, they got a room slightly larger than other families, who made do with a space 20 feet by 24 feet, with up to seven people inside.

“The room had one light bulb hanging from the ceiling and a small coal-burning stove in the corner to provide heating. That was it,” he said. “No furniture. No water, no kitchen, no potty, just a small vacant room. Oh, we were given two thin blankets and a small pillow.”

Long history of racism

Government officials created the detention centers after the Pearl Harbor attack. But the move capped decades of anti-Asian sentiment in California and across the country as white farmers and fishermen claimed the newcomers were taking their jobs by working for lower wages. In 1913, white lawmakers banned Chinese and Japanese immigrants from owning property, but babies born in California to the immigrants were citizens, and the families began flourishing. They bought land to farm, opened stores, went to college and became doctors and dentists.

That mattered less and less as World War II approached. Although people of Japanese descent represented just 1.6% of the population in California at the time, they became an increasing target of racial harassment. U.S. Sen. James Phelan, who helped pass the alien land law banning Asian immigrants from owning land, ran his 1920 reelection campaign on the slogan "Keep California White."

Asian immigrants were drawn to the young United States beginning in the late 1800s by the promise of work and opportunity. Railroads used Chinese laborers to blast through the mountains and lay the steel tracks connecting the coasts, and Japanese farmers and fishermen came to California and Mexico for the promise of better harvests.

Even today, many Asian Americans consider the routine racism they encounter as simply the cost of participation in American life.

"The fact of the matter is the United States has done a pretty good job of creating a narrative of being the land of opportunity,” said William Wei, a University of Colorado history professor specializing in Asian life in the United States. "There's a reason people come to America. The American story and its promise as a land of opportunity has been a very, very compelling story. They see the promise of something as better for themselves and their families, and they know they can't get that in their country."

Tensions between white and Japanese Americans quickened as Japan entered WWII in 1940, and reached a fever pitch with arrests of accused Japanese collaborators after the Japanese Navy attacked Pearl Harbor, killing more than 2,000 people. Although there was no evidence any of the arrestees posed a threat to the United States, the government also froze bank accounts of many prominent Japanese Americans.

Meet the ‘Angel of the Alamo’: Adina De Zavala’s grand stand in 1908 saved a landmark of Texas history

Baseball’s stolen legacy: The fascinating story of the Negro Leagues and the man keeping the history alive

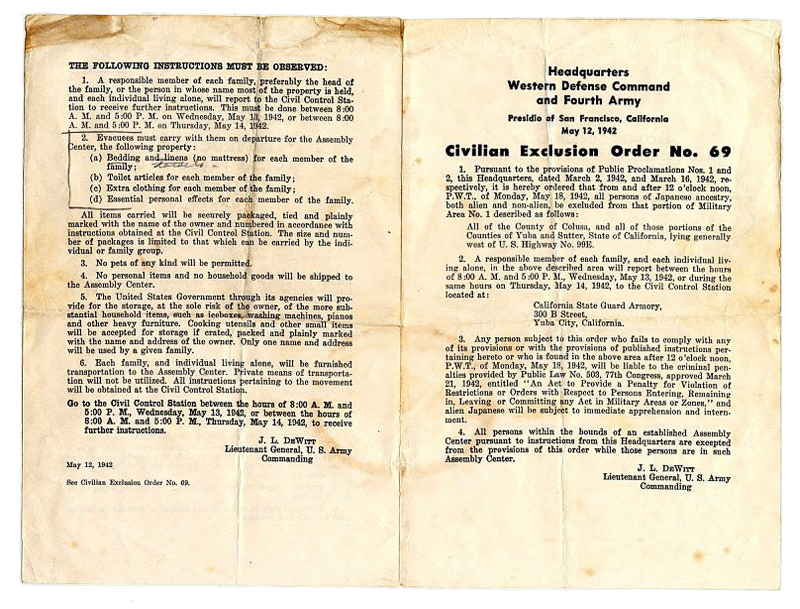

On Feb. 19, 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt gave the U.S. Army the authority to designate areas of the country where "any or all" people could be excluded for security reasons. Military leaders ordered the removal of anyone of Japanese heritage from the Pacific coastline, from California up to the Canadian border.

Although the order gave the Army permission to target people of German or Italian heritage on the grounds they could be enemy conspirators, those people were allowed to remain in their homes and to keep their jobs. Instead, angered by Pearl Harbor, many white Americans echoed the sentiment written by W.H. Anderson and published Feb. 2, 1942, by the Los Angeles Times: "A viper is nonetheless a viper wherever the egg is hatched –— so a Japanese American, born of Japanese parents –— grows up to be a Japanese, not an American."

Immediately after Pearl Harbor, many Japanese Americans volunteered for military service, eager to show their loyalty. Most were rejected as security risks. Roosevelt's order ripped apart communities all along the coast, and the policies that followed stole as much as $5 billion in inflation-adjusted dollars from detainees.

For a few months after Roosevelt's order, thousands of Japanese Americans self-evacuated from the coastlines, fleeing to states like Colorado that already had a small Japanese American population, which was exempt from the order. All, including those who were U.S. citizens, were banned from owning firearms or radios.

In late March 1942, the Army ordered people of Japanese heritage in the coastal evacuation zones, citizens or not, to assemble in several interim holding camps, ultimately forcing 120,000 people to leave behind their homes and businesses, their bank accounts and virtually all of their belongings.

Block by block, neighborhood by neighborhood, they were ordered to report to assembly yards, where they were held for months before the federal government packed them into railroad cars and dispatched them to camps in six states.

Among those detained by their own government during the war: 17,000 children under 10 years old, 2,000 people over 65 years old, and 1,000 "handicapped or infirm people," according to federal statistics. None were asked about their loyalty to the United States until February 1943, nearly a year after the first of them were detained.

"No one ever asked them if they supported the war. They were just taken away because they were Japanese," said Mitch Homma, whose father was locked up at Amache as a child, along with his father's two siblings and their parents.

Homma's grandfather died in Amache at 44 years old. He had been a well-respected dentist in Los Angeles before the war, counting actress Shirley Temple among his clients. When the evacuation order came, however, the family was forced to sell virtually everything it had, although a camp administrator permitted Homma’s grandfather, Kyushiro Homma, to bring his dental equipment to the camp, where he worked until his death from a heart attack.

"My family came to the U.S., went to school, worked hard and started their lives and then had it all taken away. They lost everything," Homma said. "I knew not to ask my dad too much. It was too painful for him. He would say that Amache took his father away."

Intergenerational trauma

Today, the windswept ground of Amache barely tells the story of the 7,500 people locked up in this camp and nine others like it around the country. Congress is considering action to formally designate it as part of the National Park Service to raise its profile and make it easier for Americans to understand what happened.

The Senate unanimously approved the bipartisan legislation on Feb. 14, sending it back to the House, which has already passed a similar version. Backers say they expect the House will accept the Senate's proposed changes – a requirement that the town of Granada donates the land to the federal government instead of selling it – and approve it later this month or in early March.

President Joe Biden is expected to then approve the law, which gives the federal government three years to develop a plan to bring the site up to National Park Service standards, which likely would include stationing interpretive rangers there, adding more informational signs and potentially reconstructing some of the historic buildings. Colorado Sen. Michael Bennet and Rep. Joe Neguse, both Democrats, are the primary sponsors.

Some of the same cottonwood trees that stood when the first detainees arrived at Amache still stand along the road leading from the railroad tracks. A small, almost apologetic sign directs visitors up the dirt road to the entrance area where bushes and tumbleweeds have largely overtaken the site.

A series of signs guide visitors along the bumpy dirt roads near Granada, once Colorado’s 10th-largest city, explaining how the detainees’ arrival was met with hostility from the start. In addition to the racism against people of Japanese descent, area farmers were upset the War Relocation Authority bought or seized 10,000 acres of farmland to build the camp. The signs show the schools where the kids were taught loyalty to the United States – even though they were already American citizens – the store, and the screen-printing office where detainees made Navy recruiting posters.

Detainees were required to work and could get mail, including catalog orders from Sears. Many bought grass and flower seeds to beautify their sparse surroundings, and boys joined one of the six Boy Scout troops. Because many of the detainees or their parents had been farmers in Japan and used to scratching out crops from the rocky soil, the dusty landscape of southeastern Colorado proved little challenge. Using water from wells and irrigation ditches, and mixing in eggshells, tea leaves and other compost, the detainees quickly turned the land productive, growing crops like melons and onions that local farmers had previously thought impossible to raise there.

Detainees could leave the camp with permission to walk into neighboring Granada to shop at the few stores that welcomed them, or to work in fields outside the barbed wire. But they were prisoners nonetheless, barred from going home or finding jobs outside the camp without explicit permission.

Amache was formally closed on Oct. 15, 1945, a little more than a month after the end of the war. Local residents stripped the site of anything useful, from the wooden boards and coal stoves to the furniture cobbled together by the detainees. And when the detainees left the camp, most firmly and deliberately put that experience behind them. They scattered across the country, their once-thriving communities in California an echo of what they once were.

"My heart breaks every time I hear African Americans talk about telling their sons about how to behave around police. Japanese Americans have felt that too - it's this whole intergenerational trauma that's been handed down. That's why there's so few Japantowns left – people didn’t want to live in a concentrated area. They wanted to assimilate and disperse,” said Gil Asakawa, whose wife's family members were incarcerated at Amache. “They wanted to become more American and less Japanese."

Added Wei, the history professor: "Most people who were incarcerated didn't want to talk about it because it was a violation. And when you're violated, you just don't want to talk about it. They had to be encouraged to talk about their experience, this bitter experience, and that had a profound impact on the younger generations."

Historians like Wei worry that without telling the story of Amache, it will be all too easy for a country long steeped in racism to backslide.

Former President Donald Trump, for instance, repeatedly floated the idea of ending birthright citizenship for children born on U.S. soil – a right granted by the 14th Amendment, which was passed three years after the end of the Civil War to grant citizenship to formerly enslaved Black people and their descendants. Trump also called COVID-19 the "Kung Flu" and repeatedly blamed China for the pandemic, and his comments paralleled a rise in hate crimes directed toward Asian Americans.

"The former president, with his rhetoric, made it OK for people who have believed for generations that Africans are less worthy, that Latinx people are stealing jobs," said Asakawa. "Asians have been a very easy 'other' since we came to the U.S."

Asakawa said Trump's comments demonstrate that racism didn't end after the 1960s. He worries that people fail to understand the historical significance, and the signal that Trump was sending, by banning people from Muslim countries from entering the U.S., suggesting he'd end birthright citizenship and referring to immigration of certain people as "an invasion."

"After the war, during the 1960s, there were people who realized that racism was bad. But they didn't stop thinking that way. They just stopped showing it. There was a veneer of political correctness that caused people to stuff down and hide their hate and their bigotry," Asakawa said. "The former president's rhetoric made it OK to scratch off that veneer of political correctness, made it OK to become a white supremacist."

‘Go For Broke’

The time detainees spent locked up forever altered most of them, from the habits they developed in camp to the losses they suffered during the relocation. Some learned as children to always keep quiet so as to not disturb the families living on the other side of the dividers in their barracks. Many still feel the shame of the stolen years.

Some, eager to prove their loyalty to a country that had so callously forced them from their homes, signed up for the military. Many joined the segregated 3,000-man 442nd Regimental Combat Team that became one of the most decorated units of the war. In three years, 31 Amache men were killed in combat, and the unit overall received 21 Medals of Honor and nearly 10,000 Purple Hearts. Its members also helped liberate the Nazi's Dachau death camp. Today, a granite memorial at the Amache site commemorates the men killed in action.

What was the 442nd?: Japanese Americans broke barriers at home and fought fascism abroad

Fuchigami remembers how the Boy Scout drum and bugle corps played for each Amache volunteer leaving the camp to serve in the military – and played as loud as they could so the residents of Granada could hear it.

The 442's slogan was "Go For Broke," an explicit declaration the volunteers had nothing left to lose – and everything to prove.

"They felt they had to prove they were Americans. That was the motivation," said Derek Okubo, whose father joined the Army after his release from Amache. "And that's just tragic in itself, that you had to prove you were an American."

Homma's father, who was a boy while detained in Amache, joined the Marines when he turned 18, concluding he could never live up to the 442's legendary reputation.

Okubo said his family rarely talked about their experiences inside the camp's barbed-wire fence. He said he once asked his grandmother what it had been like: "I saw a look come over her face that I had never seen before – pain, disgust, anger. She just shook her head and got up and left the table. That response told me everything about the depth of her pain."

Upon their release, members of Okubo's family regrouped in Denver, the nearest big city to Amache. Each had arrived at the camp with just a suitcase each, and they had little more when they were freed. Okubo said his grandfather worked odd jobs, and his father contributed his Army pay, and the family after saving for more than five years opened a small supermarket about two miles west from Sakura Square, the heart of the Japanese community in Denver.

Colorado Gov. Ralph Carr had welcomed Japanese Americans to the state at the start of the war, putting him at odds with the majority of Colorado's electorate, and his support prompted many Amache residents to make Denver their home after release. Carr, a conservative Republican, lost his bid for a U.S. Senate seat in November 1942 to a Democrat who attacked Carr's support for Japanese immigrants.

During the "evacuation" Okubo's family was forced to sell their store in California for pennies on the dollar, and what little they had left, they left in the care of the local Buddhist temple, which was robbed during the war.

"My grandparents had nothing to go back to," he said. "There was a lot of anger, and they used that anger as a motivator. My father would say sometimes the best form of revenge was to succeed. The government took everything away and hoped that would take their spirit. But they were determined."

The success of Japanese Americans following WWII led to the myth of Asians being a "model minority," a phrase that often traces its roots to a January 1966 New York Times Magazine article attributing the post-interment success of Japanese Americans to their work ethic, commitment to education and family life, and willingness to work jobs they knew would be financially successful. It was part of a longstanding schism that pitted Japanese Americans against the descendants of enslaved Black people, and that schism was exploited by white Americans.

"The subtext was, look at the Japanese, and why can't Black people be like them?" Asakawa said. "It basically said, 'we're all smart, we're all successful.' And it's all bull."

Wei, the history professor, said the model minority myth has helped prevent Black and Japanese Americans, along with other minority groups, from uniting under a shared banner of oppression. Many Amache descendants said the treatment of American Muslims following 9/11 echoed an all too familiar theme, and they see similar parallels with the white conservative crusade against critical race theory.

"You put people in plantations, you put people in ghettos, you put them in camps," Wei said. "We keep trying to separate out the people who are unworthy, who are unfit, who are not real Americans. The white majority instinctively believe they are under threat by a growing minority population. And they feel anxious that they and their descendants will lose their privileges and even worse, they will be treated in the same way they have treated the minorities. And that scares the s--- out of them."

After the war, decades of lawsuits and complaints by Amache and other detainees forced the federal government to recognize their treatment was both illegal and immoral. Although a small number of religious groups and civil rights lawyers opposed the detainments, the U.S. Supreme Court eventually ruled the actions of Roosevelt's administration as legal.

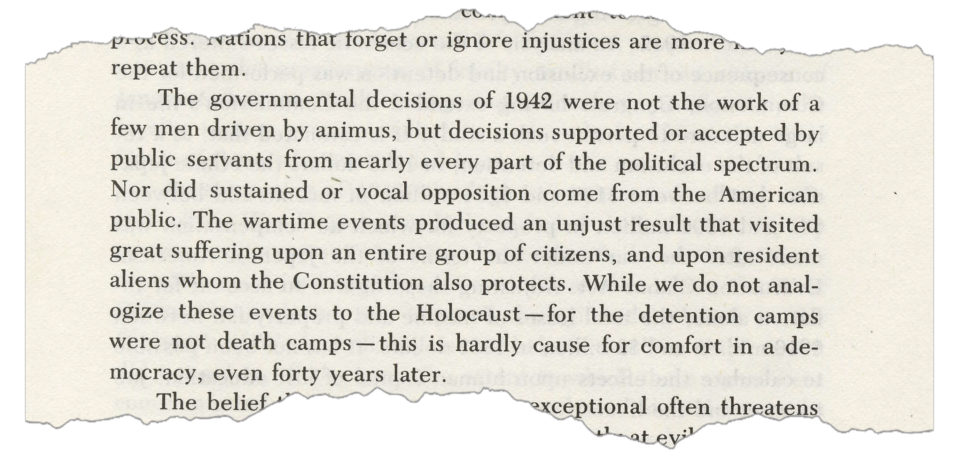

At the time, political and military leaders justified the treatment of the Japanese Americans as a military necessity, and Roosevelt himself referred to the mass detention sites as “concentration camps.” But many Japanese Americans are reluctant to draw a direct comparison between the “internment” of their families and the death camps run by Nazis. An investigation commissioned by Congress in 1980 noted the parallels – and the danger posed by populism run wild.

"While we do not analogize these events to the holocaust – for the detention camps were not death camps – this is hardly cause for comfort in a democracy, even 40 years later," the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians concluded. "The belief that we Americans are exceptional often threatens our freedom by allowing us to look complacently at evil-doing elsewhere and to insist that it can’t happen here.”

It added: "The governmental decisions of 1942 were not the work of a few men driven by animus, but decisions supported or accepted by public servants from nearly every part of the political spectrum. Nor did sustained or vocal opposition come from the American public. The wartime events produced an unjust result that visited great suffering upon an entire group of citizens, and upon resident aliens whom the constitution also protects."

In 1988, President Ronald Reagan formally apologized for the detainees' treatment, several years after a federal commission concluded that Roosevelt's original order “was not justified by military necessity, and the decisions which followed from it – detention, ending detention and ending exclusion – were not driven by analysis of military conditions. The broad historical causes which shaped these decisions were race prejudice, war hysteria, and failure of political leadership.”

Later investigations showed federal officials had hidden reports concluding the Japanese Americans posed little risk, and that there was no evidence they had or would conspire with the Japanese government.

Speaking to survivors and their family members, Reagan acknowledged the "grave wrong" committed by his predecessors. Congress also passed a law, named in honor of the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, providing $20,000 payments to each of the approximately 60,000 internees still alive – $3.5 billion in today's dollars.

"Yes, the nation was then at war, struggling for its survival, and it's not for us today to pass judgment upon those who may have made mistakes while engaged in that great struggle. Yet we must recognize that the internment of Japanese Americans was just that: a mistake," Reagan said.

While not much, those $20,000 payments and formal apologies to each survivor transformed the lives of many former internees, who finally felt seen. Okubo's relatives used the money to visit family in Japan.

"It was almost like this awaking where they were like, yeah, 'we were wronged.' I saw them go through that and recognized that they were healing," Okubo said. "My father often said there was a fine line between hope and despair on a daily basis."

After being released, Fuchigami’s family moved to northern Colorado, where a small number of Japanese American farmers had settled before the war. Colorado was one of the few Western states that permitted people of Japanese descent to buy land at the time. His parents never fully recovered from their time in Amache; his dad broke his back in a farm truck crash, and his mother had a stroke there.

A teenager by the time they got settled, Fuchigami said shame and anger kept him from talking about his family's experiences. He credits fellow Boy Scouts in Greeley with helping him regain some of his childhood joy. Long banned from becoming a citizen by racist immigration laws, Fuchigami's father in 1952 officially became an American at 68, after his five sons all served stints in the military.

"It is time for others to replace me and hopefully the Amache bill before Congress will provide the organization and resources so that our portion of American history will never be repeated or forgotten," he said.

For his part, Okubo dedicated his life to upholding the promise of the U.S. Constitution, that "all" are created equal, and that in this country we should be judged by the content of our character, not the color of our skin. And he worries that as the years pass and fewer survivors remain, America is forgetting the lessons of Amache and the other internment camps.

"People want to throw up their hands and say they're not responsible. They say, well, that wasn't me who did that. It was in the past. But what I always say is that the remnants of that still remain. And I ask, what can you do today to help remedy that?" Okubo said. "Talking about this makes our community and our country stronger. People have to hear a story over and over again to stick."

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Japanese American detainees at Camp Amache recall 1942 incarceration