1M Californians are in the dark about potential steep water rate hikes. Are you one?

Diana Juarez’ granddaughters, 9 and 11, want her to buy them a kiddie pool to splash in on triple-digit days in Niland, a tiny town tucked in California’s blisteringly hot southeastern corner. No way, she tells them firmly. With summer water bills that can approach $200 a month, “that’s just water down the drain. We can’t afford that.”

Juarez and her neighbors soon could face even higher bills. Once again, Golden State Water Company, the investor-owned utility that serves her and more than 1 million customers in 80 communities across California, has asked for rate increases. And once again, the California Public Utilities Commission is poised to approve a legal agreement that would raise rates, this time by nearly 14% for her community through 2024, and on average by 15% across the company’s service area, from parts of Sacramento and Simi Valley to Los Angeles and Orange County suburbs, and desert communities like Lucerne and Apple Valley.

The latest increases, originally set to be voted on Thursday but pulled for further review, would come atop nearly 18% increases imposed from 2019 to 2021, and decades worth of hikes before that. The new hikes would yield an estimated $54 million more in revenues, in addition to nearly $341 million earned from water customers last year. Net earnings for Golden State and its parent company, American States Water Company, were $78 million in 2022.

Part of the cash goes straight to the top: Robert Sprowls, longtime president and CEO of American States, earned $3.4 million in salary and bonuses last year.

American States, which provides water to a number of U.S. military bases, also has the longest unbroken streak of increasing dividend payments to shareholders in the country, according to trade reports. Those backers include Black Rock, Wells Fargo and other multinational investment and banking firms, per SEC filings, who, under state water laws, are guaranteed a sizeable, risk-free return on their investment.

'Why? Why do you need all those millions?'

Sprowls and American States are hardly alone. It’s all part of the costs of being served by a Wall Street-backed private water company, from California to Pennsylvania. It’s a business model that’s inconceivable to Juarez and others with limited incomes in destitute northern Imperial County, who, along with other customers, pay for it all.

“Oh my gosh ... to hear about something like that, you just throw your hands up in the air and say, ‘why, why do you need all those millions?’” Juarez said. A retired post office worker who earns about $48,000 a year, she considers herself one of the lucky ones in her impoverished town. Still, “how I live, you have to watch your pennies, to be careful how you pay your bills, you can't go on vacation,” she said, let alone give grandchildren a wet place to cool down.

Mean annual income in Niland, once a bustling railroad and tomato farming town hit hard by NAFTA and other trade policies, has shrunk to $12,110, according to US Census estimates — in sharp contrast to $78,672 for California. Many older residents subsist on low Social Security payments. It’s not much better in Calipatria, where a third of the 7,200 residents are inmates at the state prison, the city sewer system is collapsing, and residents struggle to afford water, food, electricity and other bills. Fully 85% of its residents live below the federal poverty level.

Yet the two communities’ water bills are the highest in Imperial County, per county officials who protested the rate increases when they were first proposed in 2020, and among the highest in the country. Golden State pays just $20 per 326,000 gallons of raw Colorado River water, which it then treats for household use. But its treated water costs outstrip those of Brawley, Imperial and other nearby cities.

Calipatria's five parks have no irrigated grass to play on. In Niland, front and backyards are mostly dried-up dirt or concrete, many sporting dead tree stumps or other wreckage of once-colorful gardens. Residents also complain the water is often cloudy, and tastes of chemicals. Golden States’ latest water quality report shows it is in compliance with federal drinking water standards, though a few levels near the maximum limits were found. Those who can afford it stretch their budgets to buy bottled water to drink, and shower and cook with Golden State supply.

Priming the pumps

Neither Golden State nor its parent company initially responded to requests for comment. In its filings with the CPUC, the company argued that it needs $405 million in new funds to overhaul aging water pipes and treatment facilities, as well as to repay deep-pocket institutional investors, and a $1.6 million supplemental pension for senior executives like Sprowls. About $4.7 million of the infrastructure work might go to Calipatria and Niland, which have served as far-off outposts and occasional guinea pigs for the company since it was founded under a different name, the Southern California Water Company, in 1928, according to an internal history.

In an emailed statement after this story published, the company's senior vice president of regulated utilities Paul Rowley said, “Golden State Water remains committed to responsibly maintaining the local water infrastructure to ensure we can continue providing customers with premium water service, so they never have to think twice about their water quality and customer service. This commitment is reflected in investments in the treatment and delivery of water to create sustainable, long-term value for our customers. Proactive investments to replace and protect our water infrastructure system avoids the costly and sometimes dangerous effects of deferring maintenance or delaying the replacement of aged infrastructure.”

The statement added, "I encourage you to learn more about the exemplary track-record of California’s regulated water utilities, that are proud to serve millions of customers .... They maintain an exceptional track-record of proactive system maintenance, water quality and reliability. Water rates are determined through a robust and public process that invites customer and community participation.

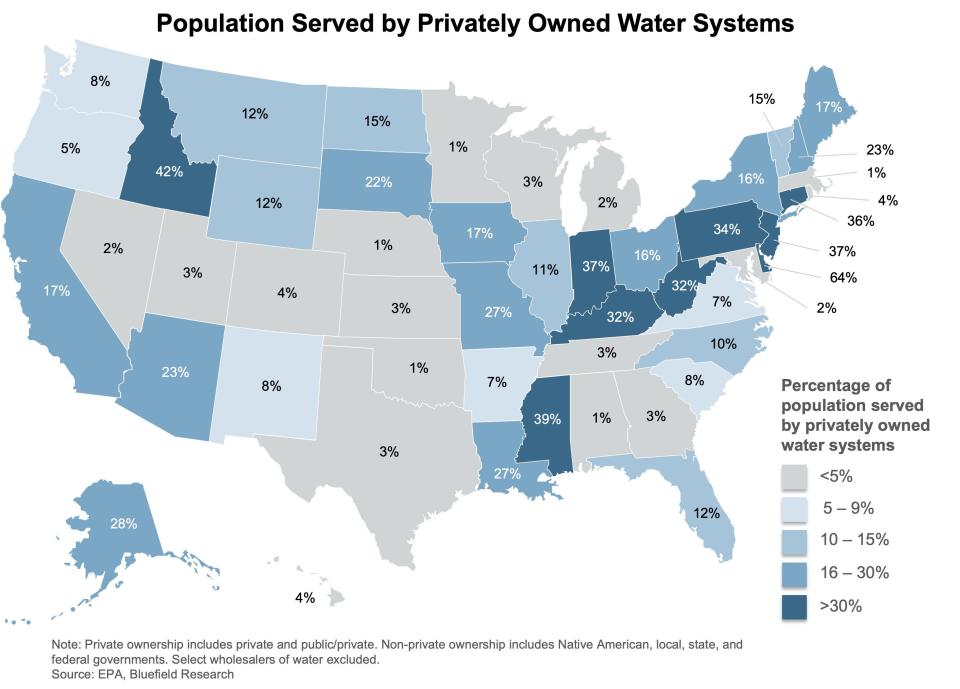

While it’s not the largest, American States is a prime example of a few dozen Wall Street-backed private water companies that, along with tens of thousands of extremely small community and tribal water companies, serve about 11% of all customers in the U.S., according to the Environmental Protection Agency. They often fly under the general public’s radar due to extremely complex regulatory proceedings and by serving sometimes widely dispersed customer bases. They also can be exempt from many public disclosure laws.

Trade groups and lobbyists for the large private companies — in many states paid for with company membership dues covered by ratepayers — note they pay property taxes and income taxes, can generally avoid political pushback that falls on local elected officials who try to raise rates, and have the necessary resources to finance long-overdue capital improvements. Independent market analysts and state regulatory staff agree with some, if not all, of those statements.

“We've lived off our grandparents and parents' investments for decades ... and the (water systems) have reached the end of their useful lives," said James Boothe, program and project supervisor for CPUC's water division. "Potable water is becoming a scarce resource, and there are additional environmental regulations that are also increasing costs."

All told, the U.S. needs as much as $1 trillion over the next 25 years to replace badly aging, leaking and often dangerous lead pipes and other outdated equipment, according to the American Water Works Association.

But the private service comes at a price: Cornell-led research published in October found that of customers of the 500 largest water companies across the U.S., according to data compiled by Food & Water Watch, most served by private companies paid higher water bills than their municipal neighbors, though Flint, Michigan, Seattle and some other public companies also had extremely high rates. Golden State's Southwest service area ranked 35th highest in the U.S. for bills, and its Region 3 area, including the two desert towns, ranked 65th highest. Coachella Valley Water District's Cove area customers also made the list, but ranked No. 473rd out of 500.

Other research has found that low-income rural areas, like Niland and Calipatria, often have lower-quality water despite paying higher rates, whether to private or public providers.

California's nine large, private water utilities, including Golden State, do offer low-income customers help via the Consumer Assistance Program, said CPUC's Boothe. Customers whose household income is less than 200% of the Federal poverty level are eligible. If the proposed rate increases pass, qualified households could get a $13.10 break on monthly bills that will average $71.67 in Region 3, which covers much of Southern California.

National consumer and environmental advocates say such funding such subsidies, huge repairs and hefty, guaranteed profits on the backs of local ratepayers is not the answer, and the federal government, which until 1977 provided major water infrastructure funds, needs to step up.

“We think that the best way to address equity issues, and make sure that every community regardless of their ZIP code, has access to clean water is for the federal government to contribute its fair share for making these improvements," said Mary Grant, director of "Public Water for All" at Food & Water Watch, a national nonprofit. She said $55 billion in the Biden Infrastructure Law is "a good down payment" but far more is needed.

Every American should expect higher water bills in coming years to tackle out-of-date, often dangerous systems, she and others agree. But if federal taxpayers footed the bill, costs would be spread far wider, she said, and would overall be far lower, with no need to pay taxes or hefty executive compensation packages, for instance.

“I would urge caution that their arguments can be rather disingenuous,” she said of private water company promoters. “Water corporations are a business … That profit motive is built into their very structure, and it is reflected in the rates that they charge households and local businesses. Unlike other businesses, water corporations have a natural monopoly on their customer base ... You as a consumer have no choice of water provider when you turn on your tap.”

She added that because they are monopolies, state public utility commissions regulate their rates, “but through that very rate regulation, the corporations are authorized to earn a return on equity (usually of about 10%) passed on to customers in the form of higher rates.”

California’s public utilities commission is actually better than many, she said. In fact, in a second decision issued earlier this month, CPUC actually denied a combined request by the state’s four largest private water providers, including Golden State, to increase their guaranteed return on investment rates, and instead reduced them slightly.

But she and others said high monthly bills and a lack of transparency are still ongoing major concerns here and elsewhere. For outraged local officials, the latest rate increases, while lower than the nearly 24% first proposed by the company, are part of a ceaseless pattern.

Toilets and turkeys — and high bills

“It’s a shame. It’s highway robbery,” said Calipatria Mayor Maria Nava-Froelich. She’s weary of Golden State staff distributing low-flush toilets and free Thanksgiving turkeys, while top executives continue to jack up monthly bills year after year with the CPUC’s approval.

“You put it all in a household bundle, the price of water, the price of gas and then this higher price of water, and man, it's going to hurt our families,” she said of the latest 14%.

Nava-Froelich said her city, strapped with other responsibilities, didn’t even submit comments this time objecting to the rate hikes. “We have fought them tooth and nail, over and over, every three years … we have submitted petitions, we have submitted comments, we have had a PUC commissioner come here years ago. But they always side with Golden State Water, not the community.”

She’s also concerned about Calipatria and Niland being lumped into a consolidated region with far wealthier Orange and Los Angeles County communities who she says can better afford the high rates.

“It’s just not a match. There’s so many iniquities,” she said.

Plenty of bottled up anger to go around

The ire in this parched, scorched southern end of the state is increasingly echoed by unhappy customers across California who are fed up with paying far higher rates to Golden State and eight other large companies than immediate neighbors served by municipal water companies. It’s galling for many that the companies not only are allowed to apply for a fresh round of rate increases every three years, but they and their shareholders are also legally guaranteed a set rate of return on their investments.

Several communities have tried to take over water service from Golden State and other private companies via eminent domain, with mixed success. Still, they take the plunge based on overwhelmingly negative public sentiment about the private providers.

Case in point: Hundreds testified at public hearings or submitted written comments to the CPUC when Golden State first proposed raising rates by more than 23% from 2022 to 2024.

“I do not consent to the price or rate increase. The amounts proposed are astronomical. We already pay overly inflated rates. Perhaps we need to be looking into the poor management of the Golden State Water Company,” wrote Sylvia Williams of Covina on May 21, 2021.

“This rate increase it just too much! This is so unfair after the year everyone has gone through. We have totally lost every bite of grass in our large backyard... there is only dirt! Yet, our water bill has steadily increased,” wrote Mari Minor of San Dimas, where Golden State and American States are headquartered.

“Please do not pass this increase. Folks are barely getting by as it is. Prices continue to increase for everything except our paycheck,” wrote David Ramos, also of San Dimas. “This proposed increase to our water is beyond ridiculous. Are you trying to put a basic need such as water out of reach and force families to choose between which bills to pay or buy groceries?”

"Commission, it is your job to protect us, the consumer, from being 'worked over' by the utility holding a monopoly (which is what is going on here). Please refuse these egregious rate increases,” wrote Anne Gardner of Tustin. “We are trying to tend to our yards and prevent raging fires."

“Instead of approving any increases to this company, you should be doing an internal audit to find where all the past increases have gone," wrote Donna Borsh of Rancho Cordova. "I would start at the top executive level and work your way down. I believe you'll find that these increases are not necessary and they need to do a better job with budgeting."

All told, 248 written comments were submitted, but likely none knows a compromise agreement was reached two years later that will be voted on this Thursday. Per standard procedure, all the opposition was summarized in a sentence in the final settlement, with no specific responses.

The CPUC does have a Public Advocate division assigned to represent ratepayers, which filed a detailed official protest to the latest round of rate hikes. From there, the application proceedings took more than two years, causing jitters for Golden State and its backers.

The CPUC process calls for an administrative law judge to hold what almost amounts to a civil trial, complete with competing expert witnesses — and then issue a proposed decision or negotiated settlement. That’s not immediately made public, but is instead handed over to the assigned member of the commission. In this case, Golden State and the Public Advocates office fought long and hard, and the statutory timeline for issuing a decision was pushed back more than once.

Finally, after company attorneys requested private meetings with the commissioner and her staff, a negotiated settlement was made public in April, months after it was reached last fall. Even then, it was only officially sent to the public advocate and the company’s attorneys. It’s on the website if you know how to navigate the process. But no copies were sent to the nearly 250 commenters or scores of officials on service lists, including mayors and county supervisors.

The company sent notices of their first proposed increased (totaling more than 23%) in 2020 via bill inserts, emails, media releases and community meetings, and was "open and transparent with customers on these rate adjustments throughout the process."

A Golden State spokesman did not respond when asked whether the company had notified customers of the new, negotiated rate hikes totaling an estimated 15% last fall, or of the vote, originally scheduled for Thursday but which was held Wednesday afternoon pending "further review."

Golden State is eager to get the latest rate increases approved. It’s preparing to submit another application for a new round of increases by Aug. 1, and according to comments its attorneys filed with the commission, they don’t want the current round of increases delayed any further because they don’t want to confuse customers.

Most people will probably scrape together the money to pay, and not even notice when the next rate increase notice gets mailed “in that tiny print,” said Nellie Perez, a Niland resident who doesn't even keep a potted plant in her yard, to reduce water costs. “It's not fair, but it's the American way. The rich get richer and the poor get poorer. Isn’t that the way it always is?”

Correction: American States Water Co. CEO Robert Sprowls earned 30 cents per month on average from Golden State Water Co. customers in 2021. An earlier version of this story quoted a GWI report that said he earned $3.36 per capita from Golden State's 1 million customers, which did not account for state regulatory limits or military base contracts and private investors who also contributed to his $3.4 million compensation.

Janet Wilson is senior environment reporter for The Desert Sun, and a Stanford Lane Center Western Media Fellow. She can be reached at jwilson@gannett.com or on Twitter @janetwilson66

This article originally appeared on Palm Springs Desert Sun: Golden State Water: Desert residents face steep rate hikes, again. Why?