The 2,000-Year-Long Search for the Loch Ness Monster

A small column in a local newspaper 86 years ago inspired a monstrous myth. The May 1933 Inverness Courier article explains how a well-known businessman and his wife were driving along the north shore of Loch Ness when they witnessed a “tremendous upheaval” in the water.

Upon stopping, they saw an enormous creature with a “body resembling a whale” sending out “waves that were big enough to have been sent out by a passing steamer.” Stunned, the couple waited around almost half-an-hour in the “hope that the monster (if such it was) would come to the surface again.”

It didn’t, but the modern legend of the Loch Ness Monster was born.

Over the years, the obsessive search for a long-necked, dinosaur-looking aquatic creature with has turned up only doctored photographs, murky water, and movie props. But earlier this fall, the mystery got a new wrinkle when a long-awaited study using environmental DNA made a splash with some surprising conclusions about what actually may be in the loch.

“Environmental DNA is a powerful new tool to understanding our world,” Neil Gammell, University of Otago geneticist and team leader for the project Loch Ness Hunters, tells Popular Mechanics, “And we are building a relatively accurate picture of life in the loch. While no reptiles were found, it is plausible that there are [other creatures] of unusual size in there.”

Ancient Origins

The Loch Ness is a murky 22-square-mile loch (Scottish Gaelic for “lake”) with an official maximum depth of 754 feet in the remote Scottish Highlands. That makes it the largest body by volume of freshwater in Great Britain. But unexplained phenomena involving Loch Ness predates that fateful drive in 1933. In fact, humans have seen something lurking in its depths for millennia.

A first-century Pictish stone carving depicts a large-headed animal with flippers that some have said looks like a swimming elephant. “The way humanity works is that we rationalize and revise mythologies,” says Adrian Shine, leader of the Loch Ness Project and long-time researcher.

In various 1,500-year-old texts, sea serpents, water horses, and water kelpie were all observed in Scotland's waterways. The earliest written sighting comes from a 7th century biography of the missionary St. Columba, the saint responsible for converting Scotland to Christianity in the mid-6th century. In this text, St. Columba meets a group of locals burying a companion killed by a water beast. By tapping his staff, St. Columba brought the man back to life. Then, the saint ordered one of his disciples to swim across the loch to retrieve a boat for the men. As the disciple swam, he was pursued by the same water beast.

But St. Columba, with the help of prayer, persuaded the monster to leave the man alone. The beast plunged back into the water and the thankful locals converted to Christianity on the spot.

The fact that that there are stories of a creature in the Loch Ness that dates back 1,500 years and continues through today is proof enough that there really is something down there says Gary Campbell who, with his wife Kathy, created the Loch Ness Monster sightings register.

“If this was in a court of law and there were over 1,000 eye witnesses saying roughly the same thing, the verdict wouldn't be in doubt,” Campbell says.

Recent sightings do have similarities to those from long ago. Campbell had his encounter in March 1996. “This small black hump came out of the water about a quarter of a mile away,” says Campbell, “Then, it happened again.” Wanting to provide a report, he discovered that was no real list or registry devoted to Loch Ness Monster sightings. So, he created his own.

More than two decades later, Campbell’s register has 1,111 sightings in its database. Some of them are historic accounts, like the one from St. Columba, which were found by combing through centuries-old texts. Others are modern sightings drawn from direct reports, newspaper articles, and other sources. According to Campbell’s registry, there’ve been 18 sightings this past year alone (the most since 1983), including a recent one from September 29th, 2019. It involved an unusual angular wake disturbance appearing to be much larger than one created by a duck.

Campbell says that most of the sightings reported are actually things that are easily identifiable, like boat wakes or water-diving birds. After an initial investigation, only about a third of the sightings actually make it onto the registry—and even some of those sightings aren't necessarily monstrous.

“We never say that it’s a Loch Ness Monster, rather that it’s something unexplained in the Loch Ness,” Campbell says.

A Monstrous Fake

On Campbell’s register, there are hundreds of amateur photos to go along with the submitted sightings to provide supportive photographic evidence. Many of these photos are fuzzy, out of focus, indistinguishable, and otherwise unconvincing. In other words, they are nothing like the "Surgeon's Photograph".

After the initial 1933 coverage, the Loch Ness Monster became a media sensation, showing up no fewer than 55 times in The New York Times alone over the next 18 months. Then, on April 21, 1934, the London Daily Mail ran a photo that forever changed how we saw Nessie.

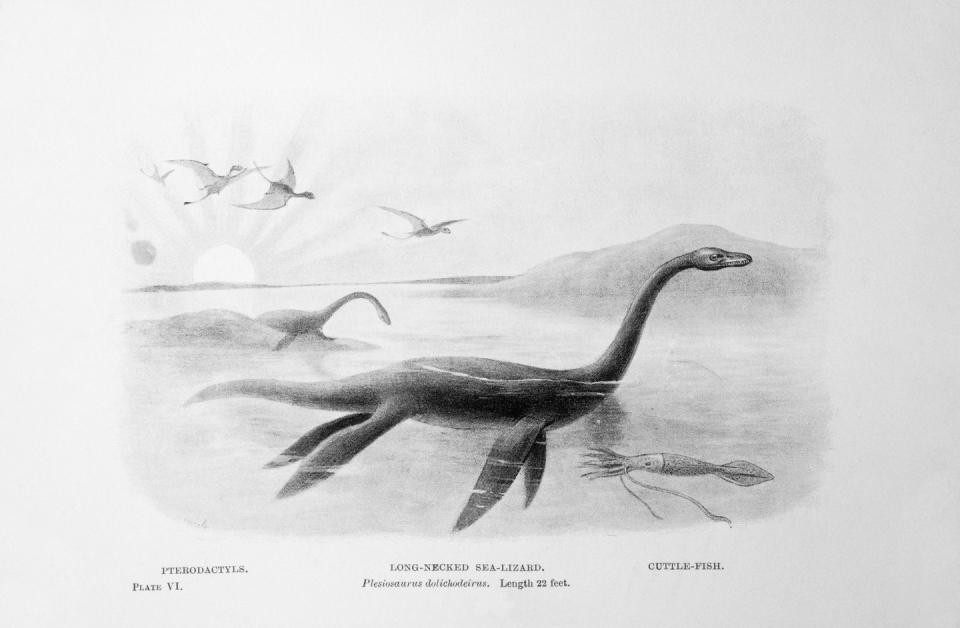

Supposedly taken by respected London gynecologist Robert Wilson, it shows a half-submerged creature with a long slender back, craned neck, and pointed face. It looks a lot like a plesiosaurus, a long extinct massive marine reptile with flippers that lived during the Jurassic era. And it set off a craze unlike any other in cryptozoology’s history, sending tourists to the Scottish Highlands to see for themselves the 65-million-year-old dinosaur-like creature swimming in the Loch Ness.

Sixty years later, it was finally established the photo was a hoax. In 1933, The Daily Mail had dispatched filmmaker and self-assured big game hunter Marmaduke “Duke” Wetherell to capture the first evidence of the creature. He returned claiming victory alongside footprint casts of a "a very powerful soft-footed animal about 20 feet long.” While initially excited, The Daily Mail sent them off to the Natural History Museum for further analysis They were of a powerful, soft-footed animal all right, but that of a hippopotamus (similar to one that Wetherell had shot in Africa). The publication called Wetherell out on his bluff, and he went back to London embarrassed.

Wetherell, looking for revenge, enlisted his son Ian and his stepson Christian Spurling to build a Loch Ness Monster. They did this by taking a 14-inch tin toy submarine and grafting a curved foot-long neck of gray-painted plastic wood to the top. Then, they attached a lead ballast strip to the bottom so it wouldn’t float up to the surface. They photographed the bobbing toy monster in the Loch Ness at far enough range to give the illusion of monstrous size. Finally, they enlisted Wilson to develop the photos and claim them as his own. To this day, it’s unclear why the doctor was coaxed into getting involved.

The whole plot was only uncovered in 1994 when two avid Loch Ness researchers discovered a 1975 newspaper clipping where Ian Wetherell owned up to the deception. While both Marmaduke and Ian had died by then, the modern-day Nessie hunters corroborated the story with then-94-year-old Christian Spurling.

“We know now that the Loch Ness Monster isn’t a plesiosaurus,” says Shine. “That era has passed. The pictures that show that are rubbish.”

While the most famous fake of Nessie, it’s far from being the only one. In 1972, a photo taken during a joint expedition of the Academy of Applied Sciences and Loch Ness Investigation Bureau (LNI) purportedly shows a “flipper-like object.” Printed in several credible journals, it bolstered the case that there was some sort of large creature in the Loch Ness. However, evidence also points to that being a manipulation. “In the end, [that photo] turned out to be retouched and turned upside down,” says Shine, “It’s a fake.”

There was also a hoax perpetrated by an overzealous cruise captain in 2013 and another one that sprang up from the deep just three years ago. However, that monster always intended to be fake.

A 2016 underwater survey of the Loch Ness done by a sea drone named Munin turned up a sonar image of something at the bottom of the loch with a distinctive long-necked shape. Yes, Munin had found Nessie, but not the real one. It was a movie prop from the 1970 film The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes that had sunk to the bottom during the course of shooting.

Loch Ness Under a Microscope

While fakes and hoaxes were plentiful, science also played a significant role in the search for Nessie. All the way back in 1904, a bathymetric survey was conducted which observed that the Loch Ness is very prone to mirages due to the deep body of water’s slow reaction to temperature changes. A distortion or elongating of a reflection was commonplace, perhaps even turning a three-foot-long water bird into one looking like three or four times its real size. Later, it would be revealed that sonar would have similar troubles when it came to temperature changes.

When Loch Ness Monster mania erupted in the mid-1930s, several biologists took their turn surveying the loch in hopes of finding a more plausible explanation. At the time, it wasn’t thought that gray seals actually lived in the loch due the freshwater and extreme cold water temperatures, but several scientists pinned monster sightings on these salmon-following mammals. As it turned out, in 1985, they were proven correct that seals could be found in the Loch Ness in the summer months due to the pursuit of their prey.

By the 1960s, telephoto lens cameras with 16- and 35-millimeter film became the main means in which to study the lock. A 1960 film captured something originally thought to be unidentifiable, but recent analysis with image sharpening revealed that it was probably a blurry boat. In the summer of that year, a joint Cambridge and Oxford expedition set up cameras to keep a large portion of the loch under constant observation. All of their 19 “sightings” were boat wakes or long-necked birds searching for fish. A 1961 BYU study used cameras and echo sounding equipment. They, too, found no large unknown animals.

Throughout the next decade, scientific expeditions kept doing surface-based investigations of the Loch Ness (mostly by the Loch Ness Phenomenon Investigation Bureau) but kept coming back with very little evidence of a large lifeform inhabiting the loch.

In 1973, Adrian Shine got involved in the scientific study of both nearby Loch Morar and Loch Ness. Using underwater photography and cameras, they searched the beds for any signs of large animals. While they didn’t find Nessie, they do find previously unknown invertebrates like worms, slugs, and eels living in the dark, cold depths of the Scottish waters. Sonar became an important part of the search in the 1980s with Operation Deepscan, utilizing Lowrance echo sounders to create a “sonar curtain” around the loch. They mostly got false positives, interference, and the possible seal.

In the 1990s, a three-year study of the Loch Ness’s food chain revealed that the loch’s food sources probably couldn’t support any sort of population of massive, omnivorous animals. Then, in 1994, Shine led the Rosetta Project with the intention of drilling sediment cores to document the environmental history of the loch. The loch’s approximate age was already known to be 10,000-12,000 years old, but the remaining question was whether the sea had entered the loch at the end of the Ice Age (about 12,000 years ago). The thought was that if a late Jurassic/Cretaceous-age creature lived in the loch, it would have had to made its way to the loch around this time.

The project came away with no evidence that the sea entered into the loch at the end of the Ice Age (and no dinosaur-like monster came with it). Shine says this was the beginning of the end of him believing that a plesiosaurus lived in the Loch Ness.

“I’m not looking for Nessie anymore. That ended 20 years ago and it’s pretty old hat,” says Shine. “But we are still solving the mystery of what people are seeing. And we now know, for the most part.”

The Monster Reemerges

While growing up in New Zealand in the 1970s and early 1980s, Neil Gammell consumed anything about the Bermuda Triangle, aliens, and the Loch Ness Monster.

“I was a skeptic, but it sure was fun to read about,” chuckles Gammell.

Today Gammell is one of New Zealand’s leaders in environmental DNA research and describes his work as collecting “all the bits and pieces we leave as we pass through an environment. Whether that be flakes of skin, eyelashes, poop, or pee.” In recent years, his work began attracting attention from cryptozoology researchers, including those looking for Bigfoot.

In April 2017, he realized that using his scientific expertise to solve the mystery of the Loch Ness Monster could be the perfect example of using a popular legend to make a scientific point. “I was a little concerned on how this might influence my career,” says Gammell, “but it was an opportunity to talk to people about science in a different way.”

In June 2018, he gathered a team known as the Loch Ness Hunters that included experts in marine biology, evolution, archaeology, molecular ecology, aquatic species as well as Adrine Shine. Then, they descended on the Loch Ness. Over the course of two weeks, they sailed the loch collecting 250 water samples.

“Effectively, we were using a molecular net to catch the cellular material then extracting the DNA from that sequencing to see what species were present in the cellular material found in the water,” says Gammell.

Over the next year, they subjected the samples to the latest gene sequencing technology and had six different teams from around the globe worked independently to match DNA. “We were able to identify life in the loch with some level of confidence,” says Gammell.

The results, released in September 2019, discovered that there are about 3,000 species present in the Loch Ness, many living at a microscopic level. But the results also included large animals like 11 fish species, twenty mammals, and three amphibians. But, notably, no reptile DNA.

“There’s nothing remotely like that in our samples,” says Gammell. “The plesiosaurs theory doesn’t hold water, so to speak. “

What they also discovered to be in the loch was an abundance of eels as their DNA appeared in nearly every single water sample picked up by the team. Gammell says it’s plausible, though not likely, that there could be eels of unusual large size in the Loch Ness.

“I think there’s enough food in the Loch Ness for a small population of reasonably large [eels],” says Gammell. “But there’s still plenty of work to be done.”

But the study also comes with a few limitations. DNA breaks down in water in about a week, so the study was only providing a seven-day window of each sample. Which would potentially eliminate collecting DNA of transient species like seals or sturgeon, who are migratory fish and are known to swim in and out of freshwater (sturgeon is also a somewhat popular “Nessie” theory due to its crocodile appearance, possible enormous size, and rigid back).

There were also plenty of DNA they collected that they couldn’t match to a known species (about 20 to 25 percent) due to the sequences being too short, missing strands, or other anomalies. Sure, some could use this as evidence that plesiosaurs Nessies is still out there, but, much like the search for Bigfoot, the burden of proof is on finding evidence to confirm something exists.

For Gammell, this wasn’t simply about using science to unscramble a legend, but showing that environmental DNA is an extremely useful tool in learning about the world we live in. “We can now use this [information] as a baseline to look at how the environment changes due to human impact in the loch. It’s a barometer to understand change over time.”

Gammell is careful to say that one study doesn’t tell us everything about the Loch Ness. Shine wants to use environmental DNA along with another well-regarded technology to get an even more complete picture of the place he’s studied for the last five decades. “The greatest evolution of technology [in searching the Loch Ness] that’s taken place is in regard to sonar,” says Shine. “Multi-beam [sonars] attached to autonomous underwater vehicles that can get within meters of a target... gives us a magnificent resolution. And that’s only happened in the last five years.”

By using this new tech, we will only learn more about what lies deep in the murky waters of the Loch Ness.

You Might Also Like