2,200-year-old mysterious script sat undeciphered for decades — until now, experts say

Starting in the the 1950s, archaeologists conducting excavations in central Asia have discovered several dozen inscriptions in a mysterious script.

The writing system was coined “ecriture inconnue” in French and “neizvestnoe pis’mo” in Russian — which translate to “unknown writing” in English. Experts found examples varying in length from just a few characters to several lines of writing.

Since the first inscriptions were discovered, experts have worked to decipher the mysterious ancient language, but it wasn’t until March that a group of researchers from the University of Cologne in Germany successfully deciphered part of the system, according to a July 13 news release from the university.

The team detailed its research and findings about the newly-discovered language — which experts proposed be named “Eteo-Tocharian” — in a study published July 12 in Transactions of the Philological Society. Here’s what they found.

A 2,200-year-old writing system

Experts determined that the writing system was likely used between 200 B.C. and 700 C.E. in parts of Central Asia, the university said. It is associated with early nomadic people who inhabited the Eurasian steppe as well as the Kushan rulers.

Since the 1950s, most evidence of the script has been found in the present-day regions of Tajikistan, Afghanistan and Uzbekistan, the university said.

Researchers said the system likely consists of between 25 and 30 characters, and is intended to be read from right to left. So far, 15 consonants, four vowels and two ligatures — or sounds — have been identified, according to the study.

How experts cracked the code

The discovery of another ancient inscription in 2022 prompted a renewed look at deciphering what was then known as the “unknown writing.”

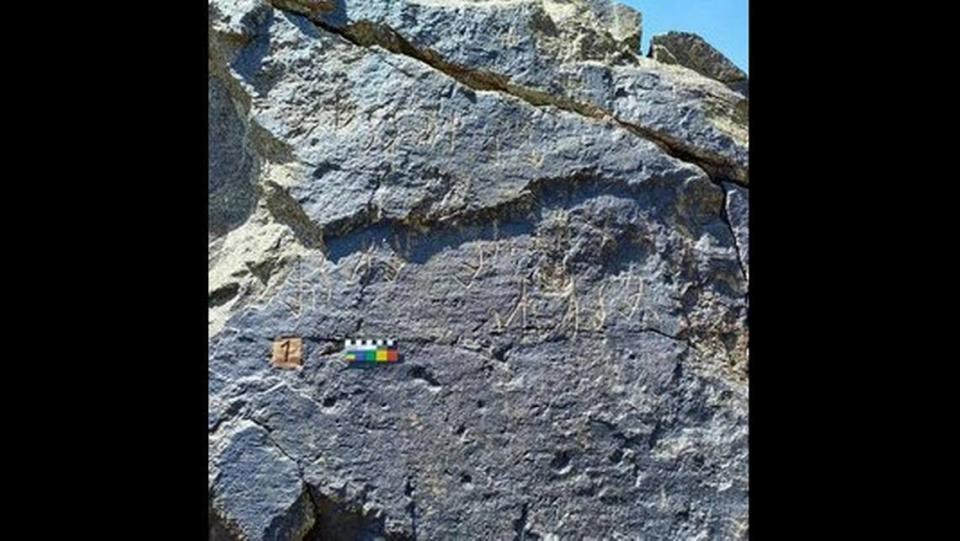

A short inscription was discovered on a rock in the Almosi Gorge in Tajikistan, but unlike previous examples of the writing system, this inscription was made in two different scripts, the university said. One version of the inscription was written in the unknown Kushan script while the other version was written in Bactrian script — a system known to researchers.

Researchers also relied on another multilingual inscription which was discovered in the 1960s at Dašt-i Nāwur in Afghanistan, the university said.

The Dašt-i Nāwur inscription is a trilingual royal stone inscription about a Kushan emperor, according to the study. It includes lines in the Kushan language, Bactrian language and a third ancient script.

Experts used translations of the Bactrian scripts on both inscriptions to help them analyze the Kushan characters and ultimately decipher the system, according to the university.

A historical breakthrough

Experts concluded that the language is a previously unknown Middle Iranian language that likely served as a middle language between the development of two known languages in the region — Bactrian and Khotanese Saka, the university said.

Although it is still unclear where the language was used, there is evidence indicating that it was an official language of the Kushan Empire, according to experts.

Further analysis will grant researchers more insight into the cultural and geographical landscape of the region during the first and second centuries.

The Kushan dynasty

The Kushan dynasty ruled most of northern Indian, Afghanistan and parts of Central Asia for the first three centuries, according to Britannica.

The dynasty was known for its hand in spreading Buddhism and its trade with the Roman empire.

This puzzle sat unsolved for 2,500 years — until one student had a ‘eureka moment’

Legend claims there’s entrance to Underworld in Mexico — and experts think they found it

Mysterious 6,000-year-old ‘Stonehenge’ structures reemerge in Poland. What are they?