Can 2 amateur historians save a Civil War battlefield from a highway interchange?

Dennis Harper and Wade Sokolosky know the Civil War Battle of Wyse Fork as well as anyone.

Harper, 72, grew up on the battlefield east of Kinston and has found more than 15,000 bullets, belt buckles and other artifacts from the conflict since he came across his first Minie ball at age 11. Sokolosky, a 25-year veteran of the U.S. Army, co-authored a book on Wyse Fork, where more men were killed, wounded or captured than in any Civil War battle in North Carolina except one.

They know precisely where Confederate and Union soldiers were over those four days in March 1865. They know where they dug trenches or hastily built bridges over creeks, where the lines began and ended and where men died and were buried in mass or unmarked graves.

Where some see only a soybean field or a tree line, they see regiments from distant places hunkering down or moving to attack.

“The 23rd Massachusetts was all in this place right here where the mobile homes are,” Harper said at one point as he drove a visitor around the battlefield.

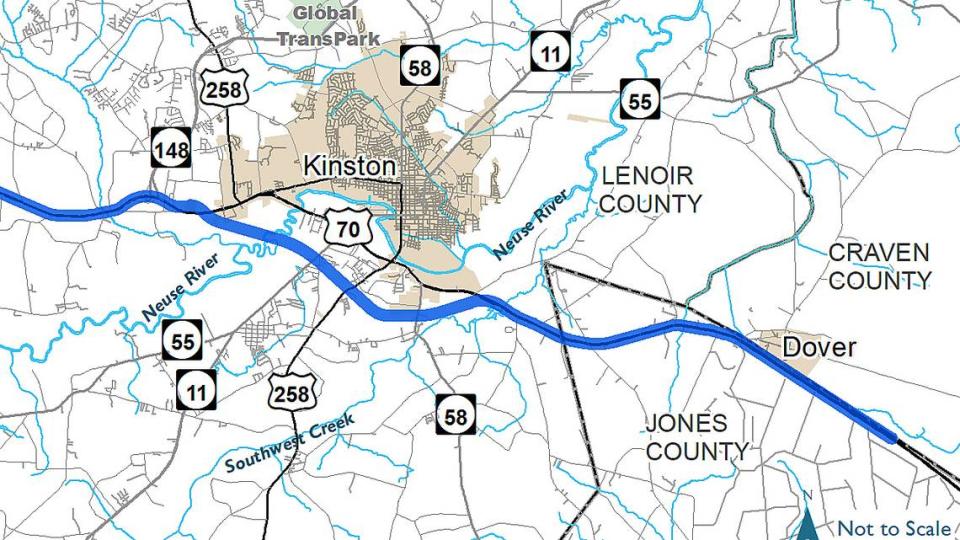

The battle ranged over 4,069 acres, but these days Harper and Sokolosky are worried about one place in particular. The N.C. Department of Transportation plans to convert U.S. 70 into an interstate highway, I-42, through the battlefield and proposes building an interchange at Caswell Station and Wyse Fork roads.

That’s the spot where three regiments of North Carolina Confederates charged into a line of Union soldiers from Ohio, Indiana and New York on the final, decisive day of the battle. NCDOT’s initial plans for the interchange cover 55 acres where Union Maj. Gen. Jacob D. Cox repelled the Confederate attack.

“That one interchange literally wipes out a good part of Cox’s defensive line. It just wipes it out,” Sokolosky said. “Losing that very key piece of battlefield ground, where American soldiers fought and died, that’s what spurs me on.”

NCDOT has looked at alternatives

Harper and Sokolosky created the Save Wyse Fork Battlefield Commission, a branch of a local preservation group, in hopes of persuading NCDOT to move the planned interchange a mile or so east or perhaps do without it altogether. They’ve erected a billboard near the site and solicited letters of support, including from legislators such as Republican Rep. Jon Hardister of Greensboro, the second-highest ranking member in the House.

“The battlefield is rich with history, and the loss of it would be devastating to the tourism of the area and the state as a whole,” Hardister wrote to state Board of Transportation members earlier this year. “We still have time. There are many other alternatives that will save this treasure of the counties of Lenoir and Jones and the state of North Carolina.”

In late July, Harper and Sokolosky met with now outgoing Transportation Secretary Eric Boyette and came away encouraged that he might intercede.

But NCDOT has ruled out moving the interchange. There are no good roads to connect the relocated interchange to surrounding parts of Jones County, and building them would be expensive and eat up more land, says Heather Lane, an NCDOT engineer involved with the project.

As for not building an interchange at all, that’s still an option, Lane said, but it would mean people in northwest Jones County would have to drive farther to access the future interstate. Even without the interchange, NCDOT would build a bridge connecting Casewell Station and Wyse Fork roads over the highway and to new service roads on either side, taking about 12 acres of the battlefield.

A third option is to redesign the interchange to make it smaller, something NCDOT estimates it could do in about 30.5 acres.

“We’re looking at shrinking the interchange and seeing what ways we can optimize it to be the least impactful,” Lane said.

The conversion of U.S. 70 into I-42 includes a new bypass around Kinston. In 2018, NCDOT presented a dozen options for taking the road south of the city and asked for the public’s feedback. It also weighed each route’s impact on farmland, wetlands, streams, homes, businesses and Kinston itself.

In early 2020, NCDOT announced that it had chosen the shortest, most direct route around the city. The 6.5 miles of new roadway would have the least impact on wetlands and had the most public support, in part because it would provide the easiest access to restaurants, hotels and other businesses on the stretch of U.S. 70 that will be bypassed.

But it also meant bringing the interstate through the heart of the battlefield, with the interchange at Casewell Station and Wyse Fork roads. Lane said each route had advantages and tradeoffs and that picking one was bound to upset someone.

“Everyone has a different perspective on that, so we have to thread the needle to find the best solution out there for our project,” she said. “The process takes time, and we’re working through it.”

Confederates attack to try to stop Union advance

The Union and Confederate armies met outside Kinston in 1865 because of William Tecumseh Sherman. Having burned Atlanta and cut his way across Georgia to the sea, the Union general was bringing his army north through the Carolinas to help defeat the Confederates under Robert E. Lee in Virginia.

His 60,000 men needed food, shoes and other material, and Sherman asked that those supplies be waiting for him at the rail hub in Goldsboro. To get it there from the port at Morehead City, the Union army had to rebuild 17 miles of tracks east of Kinston. They were busy doing that when Confederate generals Robert F. Hoke and Daniel Harvey Hill attacked near Southwest Creek east of Kinston on March 8, 1865.

After losing more than 1,000 soldiers, most captured, the Union army pulled back and dug in, cutting trees and using plates, bayonets and boards to dig trenches near the crossroads area known as Wyse Fork. It was there, from a piece of high ground near where U.S. 70 runs today, that they rained bullets and shells on three regiments of charging North Carolina soldiers led by Brig. Gen. William W. Kirkland.

More than 300 Tar Heels were killed, wounded or captured, as the Confederate attack on March 10 failed. Their names are listed on a black granite monument to “Kirkland’s Attack” that local preservation groups commissioned and placed at the Wyse Fork crossroads, at the base of a sign advertising gas prices at the Mallard convenience store. The store and the monument will likely have to be moved when the interstate highway is built.

Altogether, about 2,600 Confederate and Union soldiers were killed, wounded or captured at Wyse Fork, eclipsed only by the Battle of Bentonville less than two weeks later.

The Battle of Wyse Fork was largely overlooked until recent years. Harper, Sokolosky and others in Eastern North Carolina have helped bring attention to the conflict, through research, battlefield tours, local exhibits and a successful effort to have the battlefield added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2017. Brochures for a 12-stop driving tour around the Wyse Fork Battlefield are found in visitors centers throughout the state.

Jan Parson, who heads the local visitors bureau, says people going to and from the beach will stop at Kings Barbecue, Neuse Sport Shop or other businesses in Kinston. But the people most likely to spend a night or two are there to see the CSS Neuse ironclad and sites associated with Wyse Fork and The First Battle of Kinston in 1862. Many come from out of state wanting to see where their ancestors fought.

“They’re not just daytrippers,” Parson said.

NCDOT hopes to finish the highway designs next year

About 231 acres of the Wyse Fork Battlefield have been protected from development. More than a decade ago, a local organization, the Historical Preservation Group, bought 57 acres laced with undisturbed trenches and redoubts. More recently, the state and American Battlefield Trust have purchased conservation easements, including on farmland near the planned interchange.

Harper says the easements will help prevent some of the development that can be expected to surround an interchange.

“Let me put it this way, there won’t be no Bojangles on it,” he said. “It’ll be just what you see — a corn field or a bean field.”

It’s not clear when NCDOT will get started on the new interstate highway. The state is building the road in stages between I-40 near Raleigh and Morehead City, and it doesn’t have enough money to begin the Kinston segment.

But NCDOT wants to settle on a route and finish its designs so that it’s ready to begin construction when the money is available, Lane said. For now, the fate of the interchange remains unsettled.

Because NCDOT needs a permit from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, the federal government must review the Kinston project’s potential impact on historic properties and come up with strategies for minimizing it. Among the organizations weighing in on that process is the State Historical Preservation Office, which helped get the battlefield added to the National Register of Historic Places.

In a statement, the historical preservation office said it is working with other state and federal agencies to “minimize and mitigate any potential impacts” of the highway on the battlefield.

“As this work continues and decisions are made,” the statement concludes, “we are hopeful that continued discussions and collaboration will balance the preservation and transportation needs.”