How 2 former Columbus-area natives were in middle of JFK assassination 60 years ago today

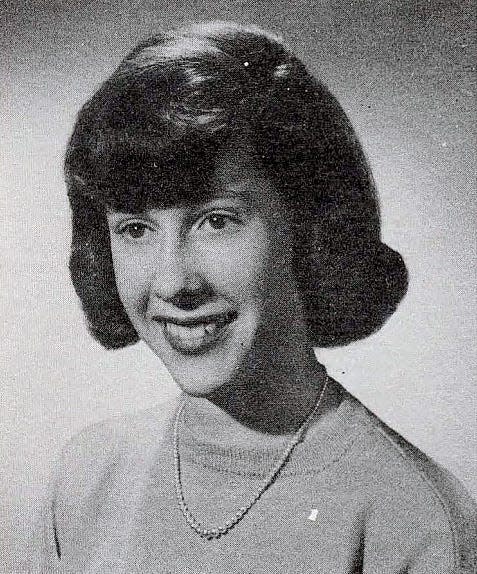

In the late 1940s, Ruth Hyde Paine was a Columbus teenager growing up in a duplex on Summit Street just a few blocks east of Ohio State University, playing field hockey, tennis and badminton in school, and preparing to study education in college.

"I could bicycle everywhere, and did with friends," recalled Paine, now 91. "I liked Columbus. It was fun."

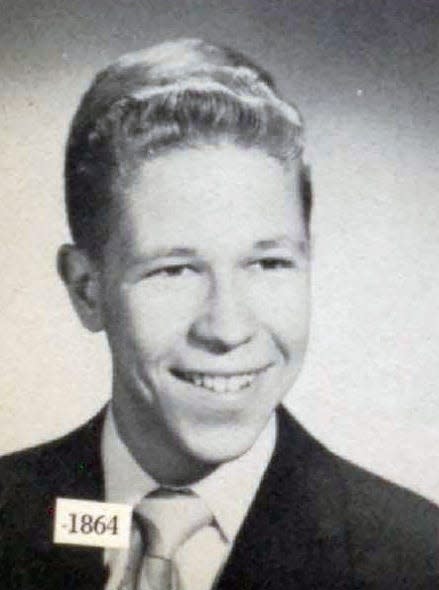

Six miles to the north, in the then-village of Worthington, another young student named Paul Landis Jr. was growing up in a three-bedroom house on West North Street, on the edge of the old section of the sleepy community. He was a few years younger than Paine, but also involved with sports — especially golf — and extracurricular clubs.

Worthington "was a quiet little community," Landis, now 88, recalled, one where if a man lost money playing poker, his wife knew about it before he got home. "You didn't lock your doors," he said, "A neighbor would come over and just holler to see if you were home."

As they went about their simple Ohio lives, Paine and Landis, who didn't know each other, had no clue what the storm of history had in store for them.

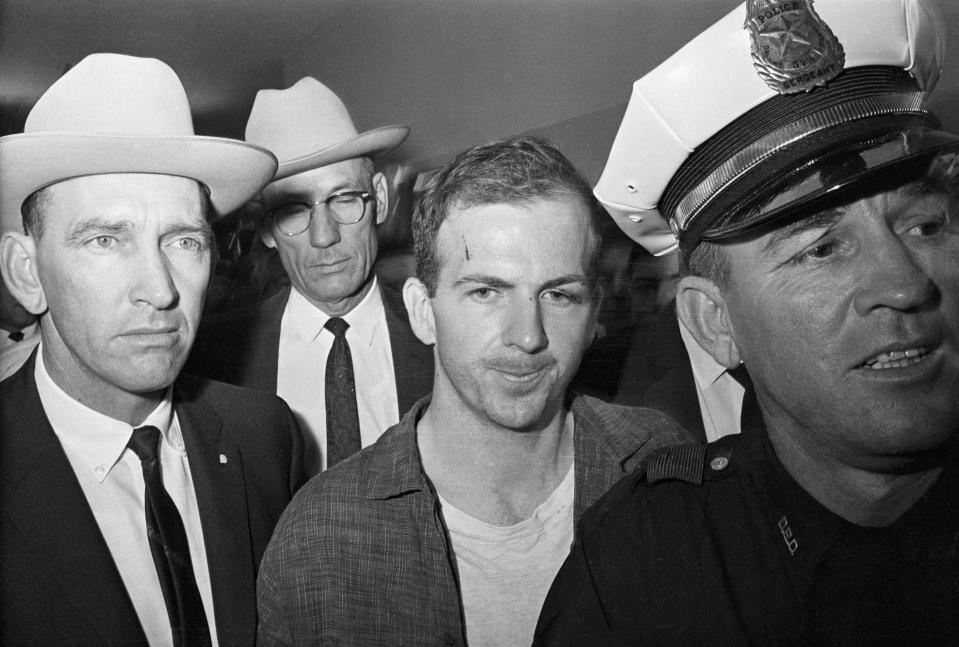

Sixty years ago, on Nov. 22, 1963, mysterious ex-Marine turned proclaimed Russian defector and Dallas warehouse worker Lee Harvey Oswald would change their lives forever.

Landis, once intent on becoming a geologist, instead landed a job with the Secret Service. His eventual assignment: protecting President John F. Kennedy's wife, Jackie. On Nov. 22, 1963, he would find himself just feet behind the open-top presidential limousine when it reached Dealey Plaza, standing on the running board of the follow-up car.

And then he heard a shot. And he scanned the area. And then he heard two more in close succession, he told The Dispatch.

"And I saw the president's head explode," Landis said. "The air filled with, you know, a pink mist of blood and flesh, and I ducked to avoid getting splattered as we drove through it."

He would follow the blood-stained first lady into the chaotic emergency room at Parkland Hospital as surgeons tried in vain to save the slain president. Later that day, he would witness the new president, Lyndon B. Johnson, sworn in aboard Air Force One as the group returned to Washington.

And just last month, Landis would fan the flames of conspiracy by releasing a new book in which he claims for the first time that he had secretly moved critical evidence linking Oswald to the killing. If true, that would further complicate the challenged "magic-bullet theory" that the Warren Commission used to cast Oswald as the lone killer.

While Landis that day was an eyewitness to the crime of the century, Paine was back at her modest suburban-Dallas ranch house watching live TV reports of the Kennedy assassination with Oswald's wife, Marina. They were shocked and saddened, Paine said.

And before the sun had set, they both were suddenly key figures in the investigation into the weird story of how Oswald came to be in Dallas, and working at the Texas School Book Depository armed with a military rifle, at the moment Kennedy's motorcade passed below.

Recently separated from her husband, Paine had met the Oswalds at a party only nine months before the shooting. Within weeks, she had struck up a close friendship with Marina, a young, Russian-born, financially struggling pregnant mother who spoke almost no English. Two months later, Marina and her young child were living in Irving, Texas, with Paine, who had two young children of her own.

"Well, I was just raised in a family that cared about other people," Paine explained in an interview with The Dispatch. "I don't know what else you could say. It was just a very normal thing to do."

Paine, who had studied Russian, had driven Oswald to the bus station when he left Dallas on his curious sabbatical to New Orleans that summer, and weeks later had driven Marina to New Orleans to reunite the family. Then she drove back and picked up Marina and her child to take them again to Dallas in September 1963. Oswald would follow later.

Paine said she was concerned about the pregnancy, and hoping to get Marina her first prenatal care in Dallas before she gave birth to Oswald's second child that fall.

But Paine has said she believes that when she drove Marina back to Dallas she also unwittingly transported Oswald's Italian-made Mannlicher–Carcano rifle with her, hidden in a large military duffle bag he had packed into her station wagon. Upon arriving in Irving, she stored the bag in the single-car garage of her house, now a museum.

"He was loaded and dangerous, and I didn't know that," Paine told The Dispatch.

And it was Paine who heard from a neighbor about a potential job at the Texas School Book Depository in mid-October 1963, even calling the head of the warehouse to secure Oswald an application interview the next day. And it was at Paine's house where Oswald stayed on weekends, and unexpectedly showed up and slept the night before the Friday shooting, retrieving his sniper gun from the garage and catching a ride with a neighbor into Dallas.

All of this would have law enforcement officials more than a little curious about Paine after Oswald stood accused of killing both Kennedy and Dallas police officer J.D. Tippit within a 45-minute span.

While Landis was guarding the stunned Jackie Kennedy as she returned her dead husband's body to the nation's capital, Paine and Marina were being visited by a group of some six police officers intent on searching Paine's house immediately — without a warrant. Paine let them.

Within hours, Paine and Marina would be at the Dallas police department's Downtown headquarters being questioned, but were soon released. Then Paine quickly found herself explaining her association with the Oswalds to the national news media, whose representatives were flooding into Dallas for answers.

Paine's explanation has remained consistent ever since: She met the couple at a party, took a sort of interest and pity on the wife — pregnant, in a new country, unable to speak the language. She thought that Marina could help her improve her Russian-language skills, which she had been working on for several years to promote foreign-exchange programs.

Paine's hometown newspapers honed in, as they realized the then-31-year-old was a "Columbus girl."

"Mrs. Oswald's Pal Ex-Local Woman," said a headline on the front page of the Columbus Citizen-Journal eight days after the assassination, atop a story recounting Paine's version of events leading up to Kennedy's death.

The Dispatch ran a story on page 2A of the Sunday, Dec. 1, 1963, newspaper that asked if Oswald had "contacts in Ohio — on the campus of Antioch College?" The then conservative-leaning Dispatch never answered its own question, but noted Paine had previously attended Antioch, the Yellow Springs, Ohio, college the newspaper noted was long a bastion for free-thinking liberals, and associated with a recent pro-Cuba student demonstration at the Ohio Statehouse. The story also mentioned in passing that Paine had attended Ohio State for two quarters.

The supposed Antioch connection was based solely on an anonymous "high ranking police officer who said he was checking reports that Oswald visited the campus" two months before the shooting. The police officer "preferred not to be identified," but The Dispatch printed the local addresses of Paine's mother and father, who had divorced in 1961.

And it identified her brother, a Yellow Springs doctor, who said he didn't know anything about Oswald, but "did admit he had carried a sign during a demonstration at Yellow Springs several months ago against a barber who refused to cut the hair of a Negro."

The story also noted that Paine told a "newsman the Russian language is a hobby of hers," and that she was "a Quaker and a Pacifist."

"The Columbus Dispatch was never too keen on me, or Antioch College, which they thought was just full of leftists, or something like that," Paine, now a California resident, told the newspaper last week. "So here I was, (on) the wrong side of the political divide."

Asked if she would consider her family progressive for the 1950s and 1960s, Paine replied: "For that particular town, for Columbus, Ohio, we were. … It was not very international, (or) very interested in the rest of the world."

Paine recounted that her father had once become very upset that, on a car trip to Indiana to a youth gathering, a restaurant wouldn't serve their group because there were Black students in their party.

FBI descends on Columbus and Yellow Springs

Following the Kennedy assassination and Jack Ruby's slaying of Oswald while the latter was in police custody, FBI agents checking out Paine's connections to Oswald swooped into Columbus to knock on the doors of family members and their neighbors, according to Warren Commission records available online through the Assassination Archives and Research Center. The Library of Congress calls the center "the largest private archives in the world" on political assassinations, including 35,000 documents on the JFK shooting.

The FBI couldn't locate Paine's mother, Carol Hyde, at her listed address in the 4000 block of Glenmawr Avenue in Linden. The house was empty. A neighbor told the FBI that she was an ordained minister at the First Unitarian Church on Weisheimer Road in Clintonville, and was away studying seminary in Oberlin.

The report also noted that a confidential informant had reported that Paine's mother in 1954 had been a speaker during a meeting of the Women's International League for Peace and Freedom at a house on East Como Street in Clintonville, where an anti-war movie was shown.

Hyde had "admitted to many neighbors during the past years that she was a 'Communist,'" the FBI wrote, and noted that daughter Paine "was a student at Antioch College."

While her father, William Hyde, worked for Nationwide Insurance, he took a multi-year leave of absence to work for the United States Agency for International Development, Paine said. That agency was established under Kennedy in 1961 to manage federal foreign assistance programs.

"He worked with USAID in Peru, helping set up credit unions, and he was so thrilled to be able to do something that seemed like it was really helping people," Paine said. "People had a little bit of money, but they didn't have the ability to have a bank account, because they didn't have enough money. But a credit union would make it possible for them to improve and save some money."

A document in the National Archives dated Dec. 5, 1963, and stamped "Secret," says that William Hyde, who at the time of the assassination was living in an apartment on the southeast corner of Goodale Park near his job at Nationwide, "was under consideration by this Agency for a covert use in Viet Nam in 1957 but was not used."

Paine has repeatedly and consistently denied for decades that she has ever had any ties to any intelligence agency. And she dismisses any version of events other than a crazed Oswald acted alone.

"There are still a lot of people who think it was a plot, but that's because they really don't know what happened. …There are some people who think there was plot to kill the president, and it really was just Oswald's impulse.

"It bothers me that people think so poorly. They don't really research, and they grab ideas. ... I'm not going to change their mind. They're going to believe what they believe."

The eyewitness, the shots, the bullet

Like Paine, Landis has long believed that Oswald acted alone — even though his first impression was that the sound of the fatal head shot had come from the front right of the motorcade, the so-called "grassy knoll" area. He stated so much in a Secret Service report immediately after the shooting.

As the motorcade took the sharp turn onto Elm Street to pass the Texas School Book Depository, Landis said he heard the first shot ring out over his right shoulder from the direction of what was later identified as Oswald's sniper nest in the building. The second shot also came from that direction, and Landis thinks it may have missed the car entirely, as he saw no obvious reaction.

The third and final shot clearly fatally wounded Kennedy, Landis said.

Landis, who left the Secret Service several years after the assassination for a quieter career in the business world, seemed to say in his initial eyewitness report from 1963 that there were three shots, but he referred to two of them as the "second" one. "I just made an error talking about the third shot," he said, saying it's clear from his entire statement that he was describing three shots.

Like Landis, another Secret Service agent in the same follow-up car, Glen Bennett, referred in his official report to the third shot as a second one, as in the second one in the quick burst of two. "A second shot followed immediately" the one before it, hitting Kennedy in the head, Bennett reported the day after the shooting.

In his interview with The Dispatch on Nov. 20, Landis described the final two shots as being spaced pretty closely together.

"We're talking six seconds here. First shot, pause - probably two, three seconds maybe, and then a second shot," Landis said. "And then very rapidly, I don't know, (the) timing between the second and the third was, was very short.

"We were in an echo chamber. ... I first thought it was like a sound that I thought could have been an echo, like a rapid echo."

Other eyewitnesses also said the second and third shots were spaced tightly together, potentially significant because the Warren Commission determined Oswald would have needed roughly a little longer than a couple seconds between shots to manually eject the spent shells from the rifle he used.

The new twist

The motorcade sped to Parkland after Kennedy and Texas Gov. John Connally were hit. Landis said he jumped out of the follow-up car and tried helping Mrs. Kennedy out of the limo.

"She said, 'No, no, I want to stay with him,'" Landis recalled. "And she had the president's head in her lap, and she was leaning over to cover his head a little."

The entire back seat was soaked with blood and flesh, he said.

"There were two bullet fragments right beside Mrs. Kennedy on the seat. I picked one of them up, looked at it. It was about the size of my little end of my little pinky finger. It was mushroomed like it had hit something. I put it right back down exactly where it was."

Mrs. Kennedy was coaxed to stand up and get out of the limo, Landis said, "and I saw a bullet, a completely intact bullet, on the top of the back seat, that had been hidden right behind her. It had striations on it like it had been fired."

Landis believes that was the bullet that hit Kennedy in the back, but it didn't go through him and into Connally as the Warren Commission concluded. Rather, it made a shallow wound to the president's back and fell backward onto the top of the back seat, Landis concluded.

"There is no way that bullet could have done all that damage" and ended up back where it started, behind Kennedy, where the top of the back seat met the metal trunk, Landis said. "...That's just impossible. Anybody that would know anything about ballistics — anything — that's just impossible that that could be the same bullet."

The bullet he found "didn't penetrate, and brushed out onto the seat behind him," Landis said.

Landis said he never revealed for decades that he picked up that bullet, carried it into the emergency room, and left it on the president's gurney near his feet, where he believes it was later found and ultimately became the so-called "magic bullet." He has said he just never thought about it — and then wrote a book, "The Final Witness," about it.

So, now having thought about it, does Landis still believe the lone-gunman theory, like Paine, given that there would appear even more issues with it based on his revelations?

"Yes I do, more so than ever," he said. "I have no agenda here I'm trying to prove.

"I believe Oswald did it, but I'm also open with, if somebody comes up with other evidence or proof, you know, I would accept that or analyze it. There are so many unknowns."

There's only one thing left to do to finalize the debate over Kennedy's assassination after six decades, Landis said.

"I just hope they reopen the investigation, that the government releases the information that they have been hiding, or not wanting to release to the public, and just get through this.

"Let's tell the truth, get the truth out there, and let the people decide from there."

The Columbus Metropolitan Library's Main Library and the Old Worthington Library contributed research to this story.

wbush@gannett.com

@ReporterBush

This article originally appeared on The Columbus Dispatch: How 2 ex-Columbus-area residents were caught up in JFK's assassination