It has been 20 years since a Black man represented California in Congress

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Black women in California sounded the alarm recently that there could be zero Black women in the Senate once Kamala Harris became vice president. With Gov. Gavin Newsom appointing Alex Padilla to the vacant seat in January, that became the reality.

But there’s an even deeper absence in Congress, one that’s in its third decade: It has been more than 20 years since a Black man represented California.

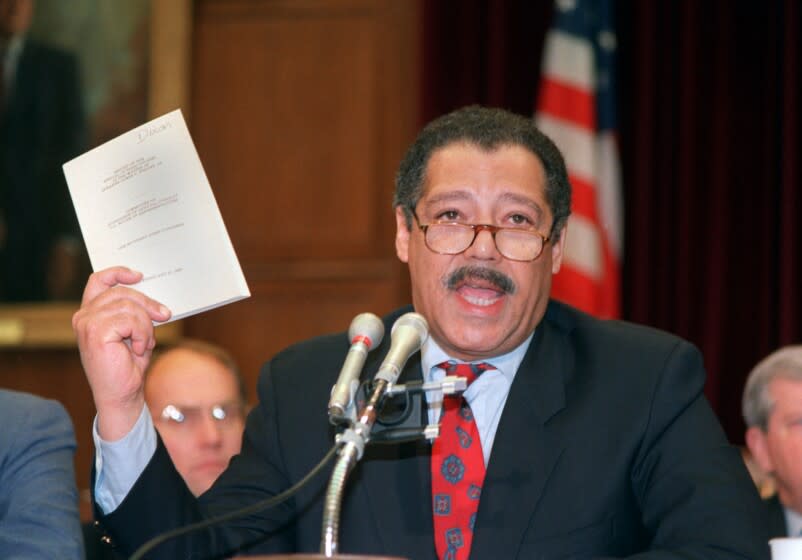

The last person to do so was Rep. Julian Carey Dixon (D-Los Angeles), who died of a heart attack in December 2000 after winning reelection a month earlier.

California, the most populous state in the nation with nearly 40 million people, is less than 6% Black, according to census data. That amounts to more than 2 million African Americans across the state.

Nearly 40% of Californians identify as Latino and the percentage of Californians who identify only as Asian is 15%.

Of the 55 Californians in Congress — 53 in the House and two in the Senate — 18 are Latino (five women and 13 men), eight are Asian American (four women and four men) and three are Black (all women).

Collective PAC, which supports Black candidates in an effort to achieve representation that matches the population, has endorsed four Black men in California this cycle: Dr. Kermit Jones (CA-04), Lourin Hubbard (CA-22), John Quaye Quartey (CA-25) and Brandon Mosley (CA-42).

Hubbard, who is running to unseat Rep. Devin Nunes (R-Tulare), and Mosley, who is running to unseat Rep. Ken Calvert (R-Corona), have long odds.

Nunes and Calvert represent districts Donald Trump won in 2020, and while Nunes’ races have been more competitive the last two cycles, he won those contests by about 6 percentage points.

Calvert has won his current district by double-digit points every cycle since it was redrawn about a decade ago.

Both Black candidates in those races have also struggled to raise campaign funds.

Hubbard was vastly outraised by Nunes and two Democrats in the third quarter, July through September, and Mosley was outraised by Calvert and another Democrat during the same span.

The most promising Black candidates of the bunch are Jones and Quartey, who still have their work cut out for them.

Jones, a former Navy flight surgeon, raised twice as much as Rep. Tom McClintock (R-Elk Grove) in the third quarter, despite getting a late start on Aug. 2, when he filed his statement of candidacy with the Federal Election Commission. Though Jones raised more — $314,000 vs. $142,000 — McClintock entered October with $90,000 more in the bank.

Quartey raised more than $250,000 between July and September, but Rep. Mike Garcia (R-Santa Clarita) brought in a million-dollar haul during the same time frame.

Democrat Christy Smith, the former state assemblywoman who lost a special election runoff and general election race to Garcia in 2020, is running a third time. Smith raised less than Quartey this quarter, but has more cash on hand.

In California, the top two candidates — regardless of party — compete in the general election, so a divisive primary campaign among Democrats risks hurting the image of the Democrat who ultimately advances to the general election next November.

Jones and Quartey are vying in districts that don't have large Black populations: Garcia’s is 8% Black (and 42% Latino), and McClintock’s is 1% Black (and 15% Latino).

Still, there’s been a nationwide trend in recent years of Black candidates proving they can win in districts that aren’t majority-Black or majority-minority.

“I think what we’re seeing is that these Black men are running in places where we don’t typically see Black candidates stepping up and stepping out to run,” said Quentin James, founder and president of Collective PAC. “Typically, you think about Oakland, you think about L.A., but there’s so many other districts across California that are diverse, that could use great leadership.”

The list of recent Black candidates winning majority-white districts includes Reps. Lauren Underwood (D-Ill.), whose district is 3% Black; Antonio Delgado (D-N.Y.), whose district is 4% Black; Jahana Hayes (D-Conn.), whose district is 7% Black; and Joe Neguse (D-Colo.), whose district is 1% Black.

“We’re excited to see so many candidates of color, including Black men, running for Congress across the map,” said Chris Taylor, a Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee spokesperson.

Tuesday’s election results in Virginia, however, will make their job even harder. Former Democratic Gov. Terry McAuliffe lost his bid for governor to Republican businessman Glenn Youngkin. The National Republican Congressional Committee, House Republicans’ campaign arm, expanded their offensive map Wednesday morning to 13 new targets, an indication of the party’s confidence in winning back control of the House in 2022.

In California, some of the districts with the highest percentage of Black constituents have long been represented by a trio of Black women: Reps. Karen Bass (D-Los Angeles), Maxine Waters (D-Los Angeles) and Barbara Lee (D-Oakland). Rep. Nanette Barragán (D-San Pedro) also represents a district with a large share of Black residents.

Ludovic Blain, executive director of the California Donor Table, pinpointed San Diego, Orange County and the Inland Empire as “emerging places of color,” where people of color have long been or are moving to due to gentrification in cities such as San Francisco, Oakland and Los Angeles.

“We’re going to have fewer Barbara Lees, Maxine Waterses and Karen Basses on the coast, compared to more folks getting elected inland and outside of L.A. and the Bay Area,” Blain said.

James said Collective PAC supports candidates through political contributions ($5,000 for primaries and $5,000 if candidates make it to the general election), fundraising and training. But challenges remain, especially in a redistricting cycle severely delayed by the COVID-19 pandemic.

No one knows exactly what the districts in California will look like for next year’s races. President Biden in 2020 won Garcia’s district, where the Republican’s margin of victory over Smith was some 300 votes. Cook Political Report rates Garcia’s district as one of the most at risk in redistricting. McClintock’s district is rated as a slight risk.

“It has been very tough,” James said, speaking to the difficulties of recruiting candidates for districts that haven’t been drawn yet. “Right now, I think a lot of folks are jumping out there without knowing who their voters will be.”

An additional barrier, James said, is sometimes having to overcome the established Democratic organizations such as the DCCC, House Democrats’ campaign arm. But those relationships have improved as Collective PAC has become more established itself.

“There are times … where we kind of have to step out there and really make space for these folks, because if you don’t know who’s at the DCCC, you don’t have a senior member of the [Congressional Black Caucus] fighting for you in those circles. You sometimes get locked out,” he said. “It’s our job, again, to make space, open up those doors, for you to even be considered. We have to make people imagine that Black people can win, like — Black men can serve in Congress in California. It sounds silly, but it’s a real thing.”

For the record:

4:38 p.m. Nov. 5, 2021: A previous version of this article misspelled the last name of Ludovic Blain, executive director of the California Donor Table, as Bain.

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.