The $200,000 Heist That Tore the 'Star Wars' World Apart

The mad world of Star Wars memorabilia collecting began with a plea for trust.

When George Lucas's film premiered on May 25, 1977, no one knew it would even succeed, much less become a decades-spanning, money-making juggernaut. Certainly not Kenner, the company tasked with making Star Wars toys. Kenner had acquired the Star Wars merchandising license only a month before the film’s release. When kids immediately fell in love with Luke Skywalker, Princess Leia, and Darth Vader, their action figures were nowhere near ready.

So, for the 1977 Christmas season, Kenner came up with an unconventional idea: an IOU. The company's $16 Early Bird Certificate Package was a box that included some stickers, a cardboard display stand for a dozen 3¾-inch action figures, and a mail-in offer to receive four of the upcoming figures (Luke Skywalker, Leia Organa, Chewbacca, and R2-D2) between February and June of 1978.

Kenner delivered on its promise. Throughout early 1978, children received the promised four figures, kindling interest in completing the full 12-piece set. These first dozen toys, known as 12-backs, went on to sell 26 million units that year, kick-starting what would become one of the biggest toy franchises in history. To date, Star Wars merch has moved nearly $20 billion in sales.

That first act of trust ignited a phenomenon. Star Wars collecting became a hobby, then a passion, then a worldwide industry with insurance policies protecting collections worth millions and collectors chasing the rarest and most elusive pieces. In 2017, that hobby would be tested by an aspiring collector, a thief hidden in plain sight, and a rare plastic action figure worth more than your average car.

In early February 2017, 39-year-old collector Zach Tann would unknowingly set in motion one of the biggest scandals in Star Wars collecting history.

The Big Find

“I have a biggie,” the text read. “Are you sitting down?”

It was February 3, 2017, and Tann, a Los Angeles talent and literary manager, was about to enter an exclusive club. Years earlier, an episode of Toy Hunter pulled him into the Star Wars–collecting world, where he became immediately interested in buying, selling, and collecting Lucasian memorabilia.

Over the next four years, Tann hit the typical collector touchstones—first, amassing his own enviable collection, and then establishing himself as a trustworthy dealer. More than that, he built out a network of other Star Wars toy collectors, finding the fraternal comfort of knowing someone else shares your obscure obsession.

The text came from one such collecting comrade, Carl Cunningham. A Georgia native and longtime collector, Cunningham had been selling off a portion of his reserve to Tann over the last eight months. Tann followed instructions. He sat, and he tried to believe what his eyes were reading.

It was a galaxy far, far away's equivalent to a Mickey Mantle rookie card. It was a purchase that would cement Tann's membership in an exclusive enclave within Star Wars collecting—a club within a club. It was one of the rarest Star Wars collectibles, a failed 1979 prototype action figure that would fetch at least $20,000 on the open market.

It was a Rocket Fett.

The Dark Times

By the time The Empire Strikes Back came around, Kenner had learned its lesson. The company braced itself for an onslaught of public demand for toys that would come with the release of the 1980 sequel. This time it would be ready.

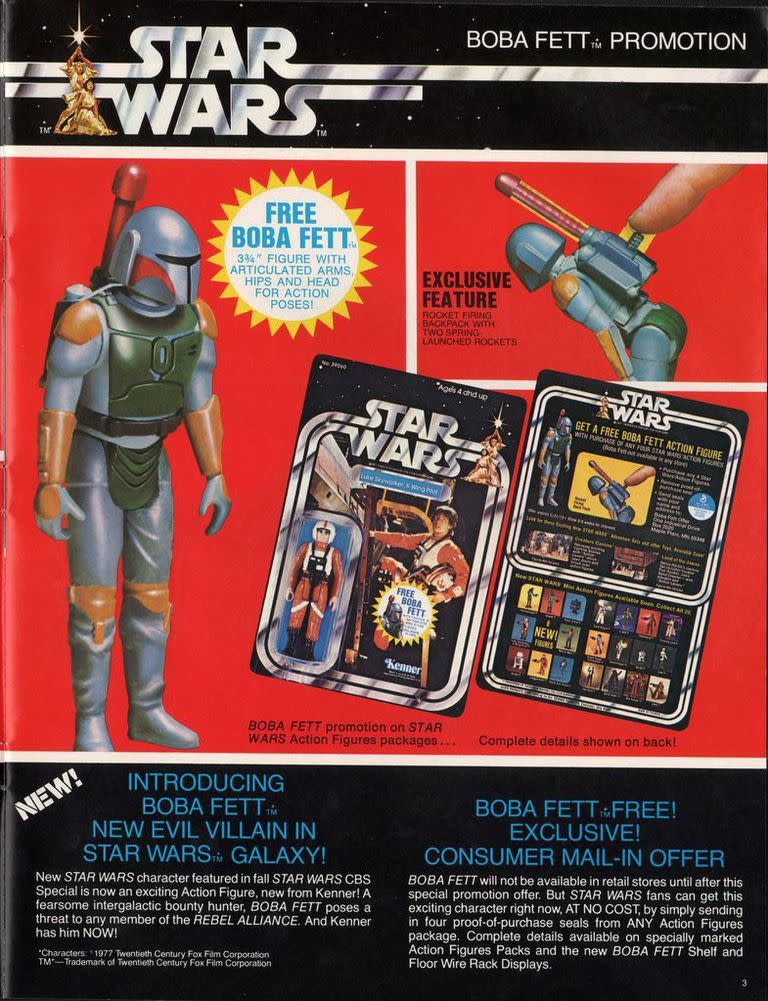

Among the promised figures in the January 1979 Kenner catalog was a new Star Wars character, a bounty hunter named Boba Fett. In a time when most action figures were little more than a torso and five twistable appendages, Boba Fett would come with a spring-loaded backpack that could fire a plastic missile.

But before the item could be released, a child choked on a similar missile, this one from a Mattel Battlestar Galactica toy. With that, the dream of Fett's projectile backpack was over, and Kenner scrapped the in-progress design and replaced it with a safer one. But this redesign came so late in the design process that several prototypes of the original Fett figure had already been made. Instead of throwing them out, many Kenner employees held on to them.

That would prove to be a wise decision. Even though, at the time, it seemed far from clear that Star Wars even had staying power, much less the stuff to conquer the world.

After Return of the Jedi left theaters in 1983, it would have been easy to assume that the franchise was done for good. The trilogy had ended. No more movies or shows lurked on the horizon. But love for the first three movies endured, and by 1985 more than a hundred different Star Wars toys had been created. But the two key ingredients for serious collecting are nostalgia and time, and Star Wars hadn't garnered enough of either just yet.

The years between 1986 and 1991, when few if any new toys were made, have become known among collectors as “the dark times.” But it was during this lull that an older generation of Star Wars lovers, who had seen A New Hope as adults, became interested in collecting Star Wars toys.

With cash to spend, adult fans turned the dark times into an opportunity to complete sets, track down rare items, and shape the principles of the hobby that would emerge later. Avenues like Toy Shop Magazine, first published in 1988, allowed collectors to place ads for phone auctions, offer direct sales, or advertise conventions, stores, toy shows, and flea markets.

With the dawn of the internet and online auctions, collectors were able to connect and exchange items in unprecedented ways, and the hobby only grew. It kept growing, and it was still growing when Tann got a text about a Rocket Fett.

What Every Collector Dreams Of

Tann was one purchase away from a unicorn. The offer was too good to pass up, and Tann paid Cunningham the asking price. “I’d been working my butt off for four years, and I felt like, finally, I found my guy that’s going to hook me up with a lot of great stuff,” Tann says. “This is what every collector dreams of.”

Cunningham was away in California at the time but promised he’d get Tann his collectible once he returned home. But a little over a week later, Tann’s phone vibrated with another notification, this time a Facebook message from a friend.

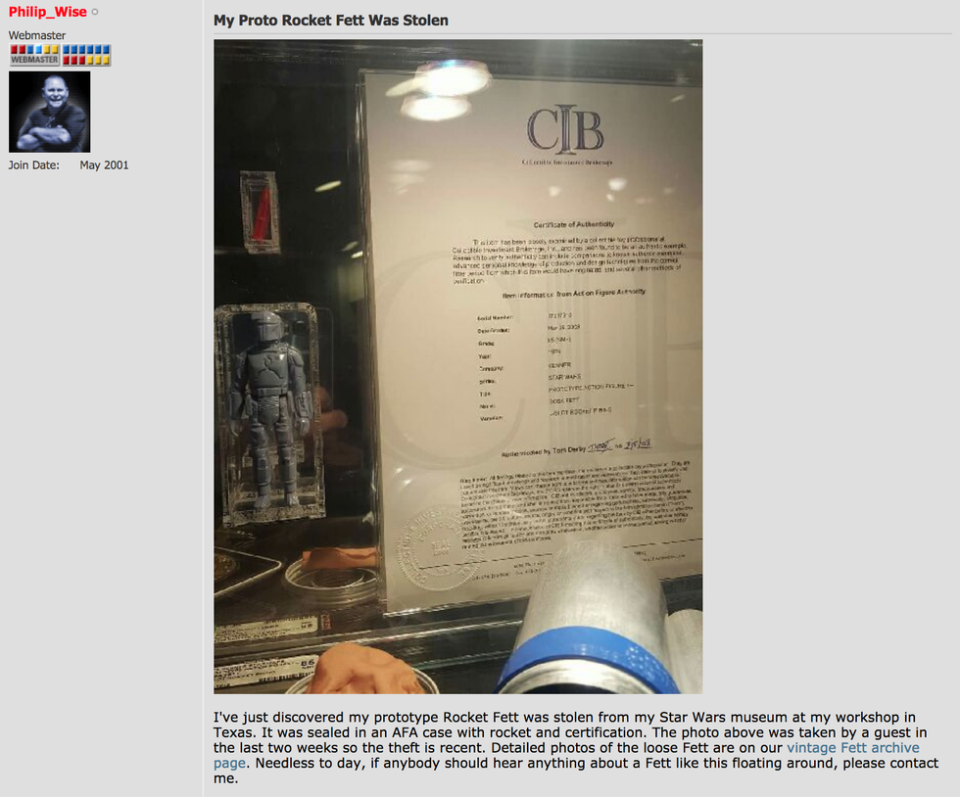

The message contained a screenshot of a post on the forum Rebelscum.com, a popular Star Wars collector website. Titled “My Proto Rocket Fett was Stolen,” the post received over 26,000 views and shocked the community. “Man this is horrible. I could just imagine the gut wrenching feeling, the pitfall in your stomach. Wow. That is messed up,” said one typical reply.

The Rebelscum post was written by prominent Star Wars collector Philip Wise, whose 20,000-item collection is a place of pilgrimage for many Star Wars collectors. Wise detailed how his Rocket Fett prototype had been taken sometime in the last two weeks from his private Star Wars museum, where it was prominently on display. He made a plea: “If anybody should hear anything about a Fett like this floating around, please contact me.”

Wise’s words punched Tann in the stomach. Cunningham couldn’t be the thief, right? It wasn't his Rocket Fett, was it?

“Your reputation will get destroyed if you scam somebody within the groups…it’s just not worth it,” Tann says. “I couldn’t have predicted then how much of a nightmare it was going to be…it was so much worse than I even knew.”

It Couldn't Be Him

What Tann did know is that if he reached out to Philip Wise, he'd be triply screwed. He might have to give up his Rocket Fett, which he hadn’t even received yet. He might be out the money he'd paid, and he'd be outing a friend. But for Tann, the choice was obvious.

He emailed Wise, and within an hour they were on the phone. Tann explained that he’d recently bought a Boba Fett prototype that could be the pilfered item. But Tann was hesitant to share the name of his seller at the risk of implicating someone who was at least innocent until proven guilty.

So they met in the middle. Wise shared that, on the advice of his local police department, he had compiled a list of suspects. Tann decided that while he wouldn’t offer up a name, he’d be willing to confirm one. He also offered one biographical detail: His seller lived in Georgia. Wise’s list contained the name of someone from Georgia. He asked Tann if Carl Cunningham was his seller.

Tann was devastated.

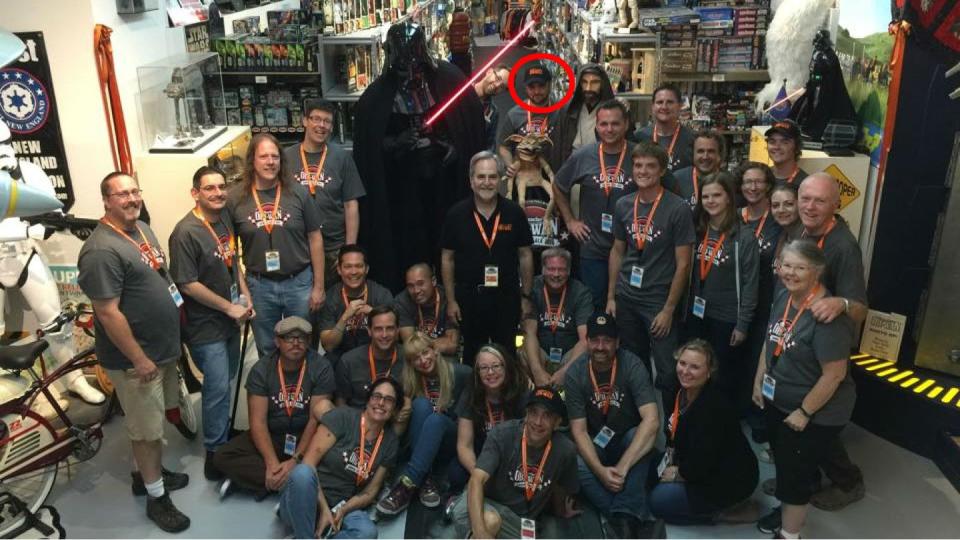

Cunningham was a reliable presence among collectors, cosplayers, and droid builders. He was a regular at San Diego Comic Con, Atlanta’s DragonCon, and Star Wars Celebrations. He had contributed Star Wars coverage to sites like Cinemawatch.net, DVDSewer.com, and Ain’t It Cool News. He was welcomed into homes with valuable collections without question, and even volunteered at Rancho Obi-Wan located in Petaluma, California—the mecca of Star Wars collecting.

“I collected just about EVERYTHING I could get my hands on,” Cunningham wrote once in a post on CHUD.com, a film news website where he was a mainstay on the forums. “I honestly can’t believe there are many people out there that accumulated as much Star Wars junk as I did.”

After talking with Wise, though, Tann's doubts reached beyond one Boba Fett. The legitimacy of the dozens of purchases he’d made from Cunningham were at stake. Were those stolen goods, too?

Tann shared a comprehensive list of his purchases with Wise and, sure enough, Wise recognized more collectibles of his. But he noticed something else, too. The large volume of items that Cunningham was selling suggested that he had been stealing from someone else.

And the quality of the collectibles left little doubt as to who it was.

Lord Collector

During the nascent days of Star Wars collecting, one man stood alone.

Stephen J. Sansweet was a 31-year-old reporter working for the L.A. arm of The Wall Street Journal when he saw an early screening of Star Wars on Saturday, May 21, 1977. He has called that day “seismic,” sparking a passion for Lucas’s hopeful universe that translated into what he has described as a compulsion and obsession. Sansweet began collecting Star Wars merchandise without discrimination—figures, posters, props, and prototypes, whatever he could get his hands on.

He became a regular at Toys "R" Us. He tracked down rare items, like a banner of an early conceptual image of Star Wars painted by Ralph McQuarrie and a life-size Darth Vader made up partly of pieces used in the filming of Empire Strikes Back. Sansweet bought and bought and bought, and by 1989, his collection contained more than 10,000 items. In time, his 1,400-square foot, one-story house in East Hollywood became a two-story house, then a three-story house, just to contain the sprawling assemblage.

In 1992, Sansweet wrote a LucasFilm-approved book called Star Wars: From Concept to Screen to Collectible. In the span of 132 glossy pages, Sansweet detailed the way Lucas realized his vision for Star Wars through conceptual art and models, which were then translated into toy form. “Collectible” may be the last word in that title, but it’s clear that's where Sansweet’s heart lies. His writing shines in the chapters where Sansweet recounts the backstories behind the merch.

“He’s really the pioneer of collecting,” says Gus Lopez, founder of The Star Wars Collectors Archive, a collector website launched in 1994.

Sansweet became an Obi-Wan Kenobi–like mentor to other collectors. Beyond his book, he shaped a philosophy of collecting. Collections were meant to be shared, and the hobby should be accessible. “It’s not the stuff,” he told GeekDad in 2017. “It’s talking about it and relating stories to people. It’s about all the fun I have interacting with fellow fans from all around the world.”

Eventually, Sansweet joined LucasFilm as a Head of Fan Relations and a Fan Liaison Consultant, helping organize conventions to drum up anticipation for the special-edition theatrical release of the original trilogy in 1997, giving dozens of presentations at Star Wars Celebration conventions and editing the official magazine and StarWars.com.

As his reputation grew and he became a visible symbol of Star Wars fandom, his collection grew with it. In 1998, he moved to a former chicken ranch in Petaluma, California, and called it Rancho Obi-Wan. In 2011, he turned it into a nonprofit museum where he offers tours to collectors, fans, and schools and relishes telling visitors the stories behind the items. His philosophy remained steadfast: He eagerly shared his collection with friends and collectors who wanted to visit, welcoming them into his home and often letting them roam on their own.

By 2013, Sansweet had amassed more than 300,000 items, covering more than 9,000 square feet. His collection earned him a place in the Guinness World Records, and it is now considered to be the epitome of all Star Wars collecting. But it’s still not as big, or beloved, as Sansweet himself.

“There’s no bigger figure in Star Wars fandom than Steve,” says Ron Salvatore, a co-editor of The Star Wars Collectors Archive. “He transcends collecting itself.”

Looking at the inventory of potentially stolen items, Wise and Tann couldn't shake their conclusion: Cunningham was stealing from Steve Sansweet, and stealing a lot.

There’s a Full Trust Here

Once the pair broke the news to Sansweet, it was time for the tedious task of inventory. As the Rancho Obi-Wan team slogged through its catalog to identify what was missing and start all the legal and insurance processes, Tann found himself haunted by self-doubt.

Why hadn't he seen the signs? Cunningham often sold valuable Star Wars memorabilia for prices that seemed a tad low. He'd often say he had nothing more to sell, then turn up shortly thereafter with a long list of available items. The most troubling, unshakeable memory was a condition Cunningham had stipulated when offering Tann the Boba Fett prototype. “No one can ever know you got this from me,” Cunningham had texted. The stated rationale at the time was that other friends would be angry he didn't offer them the rare Fett. In retrospect, the desire for anonymity had a stink about it.

Tann decided to make things right. He would get Wise his Boba Fett back from Cunningham. That meant the next time he heard from Cunningham, he’d have to do a little detective work.

On February 15, 2017, four days after Philip Wise’s post had been published, Cunningham texted Tann. After some small talk, Cunningham texted: “There's a bit of a complication, now, though, which is making me nervous."

"What's that?” replied Tann.

“You have to keep this between us, which I know you will. There’s a full trust here. A friend, Philip Wise, who owns Rebel Scum, has one very similar, and it was literally stolen about two weeks ago.”

“Did you have access to Philip in the past two weeks?”

“No, he's in Texas.” Cunningham said. "Here's the complication, I got mine, well, now yours, in a sale and trade from Philip. He had two. He's the one I promised I would sell back to him before ever offering to anyone else. But, I may see him in a few weeks.”

"Okay, why don't you just reach out to Philip and offer it back to him first?" Tann texted, seeing an opening.

"Okay, I might do that. I hate to, since it was basically a done deal for you, and I hate reneging on deals. Plus, you paid for it. But, I can't let him know I was selling it, that would be a huge no-no. Anyway, I'm sure we'll figure it all out, it's just that I logged on tonight and read about the other one. Good Lord… No idea how that could have been stolen. The last time I was there, it was locked inside a case… Unreal. And he has video surveillance. Thanks for understanding, brother, I'll get you paid back."

Tann was stunned. There, in text form, Cunningham admitted the very obstacles he would've needed to clear to steal the figure. It was brazen.

“If I honestly didn’t know the full fact that this guy stole the stuff,” Tann says, “he may have convinced me.”

The Blowup

The denials wouldn't last for long.

Once Tann had received part of his money back, Wise contacted Cunningham and said he knew Cunningham had stolen the figure.

Lying to Tann was one thing, but it was another to lie directly to a friend like Wise, now that he knew the truth. Cunningham wasn’t a career criminal, proud of what he’d gotten away with so far. Cunningham felt festering shame and regret over having betrayed those who had trusted him. Now, he had the opportunity to do the right thing after doing the wrong one for so long—even if it was likely too late.

Cunningham admitted what he had done and returned Wise’s Boba Fett. He also reached out directly to Steve Sansweet to confess that he had taken items on at least three separate occasions throughout 2016 while volunteering at Rancho Obi-Wan.

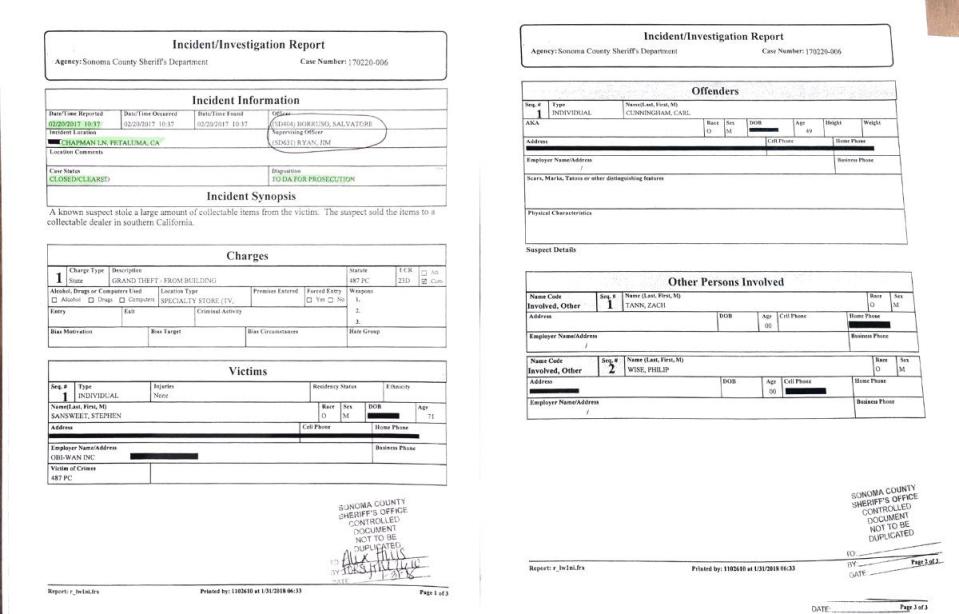

Sansweet filed a report with the Sonoma County Sheriff’s Department, and the police issued a warrant for his arrest. Cunningham surrendered on March 24, 2017, in Sonoma County, charged with felony grand theft. He plead “not guilty” because to do otherwise would have meant waiving his due process and risking instant sentencing. He posted $25,000 bail and would later change his plea to “guilty.”

His crimes—and the betrayals of two of the most respected Star Wars collectors, Sansweet and Wise—stayed quiet for a few weeks. On April 12, Wise announced on Rebelscum.com that he had received his Boba Fett back and was shocked to discover he’d been robbed by a “trusted friend of mine.”

Sansweet, meanwhile, went public about the Rancho Obi-Wan theft on June 5 with a post on the museum website where he detailed that he’d lost more than 100 items, and named Cunningham as the culprit. Given Sansweet’s fame in the community, the theft became worldwide news.

“It’s a feeling of utter betrayal that someone could stoop to this level, an alleged friend and confidant, someone I had invited to my house and shared meals with,” he told The Guardian.

Maybe publish a list of stolen items to protect potential victims from purchasing "hot" merchandise. #TheFraudIsStrongInThisOne #SithHappens https://t.co/coFv1P6HL7

— Mark Hamill (@HamillHimself) June 5, 2017

“To have a friend come in and do something like this, it could destroy your faith in humanity,” he shared with The Associated Press.

The Star Wars collecting community was quick to rally behind its ambassador.

Collectors flooded Facebook and other online forums with messages of support and hope that the items would be returned. Some Star Wars memorabilia groups held fundraisers to donate money to Rancho Obi-Wan. Mark Hamill, along with Chewbacca actor Peter Mayhew, put out a call to Star Wars fans on Twitter to help Sansweet reclaim his lost collectibles.

Many were astounded by the audacity of the crime and Cunningham’s belief that he could get away with taking something so rare. “Stealing that Boba Fett is like walking into the Smithsonian and stealing an Ansel Adams on display,” wrote one forum user.

The online mob was coming for Cunningham. One Twitter user devoted the majority of his account to harassing him. A Facebook user took photos of Cunningham standing in front of Star Wars items and Photoshopped text like “So much stuff to steal” or “Can I steal this?” on them. There were prison rape jokes, and calls for Cunningham to rot in hell.

Others looked for ways to make it personal. Emails, texts, and phone calls threatened the accused with physical violence if he ever showed himself at a Star Wars convention again. Some told him to kill himself. Someone anonymously emailed Cunningham’s employers about what he had done, and he was fired. Some fans tracked down his family, including his young children, through Facebook and sent harassing messages.

Of the nearly 20 collectors interviewed for this article, several agreed to talk about the events—but not about Cunningham. One collector refused to say his name during the conversation, but a few veteran collectors did have some things to say about the theft.

“In order to do that, you have to basically just throw out every sort of respect that you have for someone’s collection, and the effort it took to put it together,” Salvatore says.

It was as if everyone in the community wanted to turn back the clock and erase any memory of Cunningham ever belonging to the group. Almost everyone, that is.

He Didn't Want the Conflict

There's always a person beneath the public shaming.

Cunningham was a film buff with a library of hundreds of DVDs and once appeared as a zombie extra in The Walking Dead. He cosplayed as Indiana Jones, The Comedian from Watchmen, Quint from Jaws, and a variety of blink-and-you'd-miss-them Star Wars characters. He held jobs at IBM and Turner Entertainment. He struggled with the downtime of post-layoff unemployment between jobs, but filled the void with contributions to numerous Star Wars websites and DVD review sites. He even wrote a book about how to road trip to Star Wars shooting locations.

Nick Nunziata, the founder of CHUD.com, knew Cunningham for nearly two decades before the incident. The two met at film school in Atlanta in the early 1990s and bonded over baseball and Sam Raimi movies. They formed a band and shot their own movies around the city.

“He wears the black hat in the story, but he's not some monster or anything like that,” Nunziata says.

Nunziata was angry about Cunningham’s crimes and deeply disappointed in his longtime friend. He also had to reconcile this crime with the person he'd known for 20 years—the proud father who talked up his kids as often as possible.

“The hardest part of this whole thing has got to be the look on his kids' faces when they found out about this,” Nunziata says. “Because, his kids, that’s where he's always been consistent. He has never not worshiped the ground they walk on. That's always the first thing we talked about.”

Of course, years of friendship meant he knew Cunningham’s weaknesses better than most. “He used to be afraid to be truthful in some situations, or just not think about the ramifications of little white lies,” he says. When someone was telling a story, Cunningham would sometimes act as if he’d been there when in fact he had not. Nunziata and others referred to moments like those as Cunningham CGI-ing himself into their memories. But it’s an impulse that Nunziata could understand. He saw it as something born from a need to be accepted, a desire to contribute, a fear of missing out.

That could crystallize, too, when he was caught in a lie. “He just did not have the ability to confront things. So he would say whatever he needed to say to keep the pressure off,” Nunziata says. “It wasn't trying to lead somebody down a path or to hide something. I think it was just trying to keep the waters still. He didn’t want the conflict.”

Cunningham was nakedly honest about what else he was afraid of: his Star Wars collecting compulsion. “You see…I’m an addict,” he once wrote in a CHUD.com post. “I can’t say I ‘was’ because you’re always an addict for life. Some simply kick the habit and stay away from the drug. THIS is/was my drug. No joke…this is like crack to me. Same cause and effect, only slightless [sic] less harmful physically.”

He went on to ask for support. “I can’t go back on the crack, no matter HOW enticing and appetizing it may now seem. Someone PLEASE come and talk me down now before this even begins to snowball.”

He tried liberating himself in the form of a spectacle. In 2013, Cunningham posted a video to his YouTube channel that begins with a closeup of a barbecue grill, as anticipatory flames flicker beneath. “Alright, here we go,” Cunningham’s voice says off camera. Then he throws a Blu-Ray box set of the Star Wars films on the barbecue. After a moment, he sprays oil on the boxset and the flames leap to swallow it.

All of this floated in Nunziata's mind when he considered cutting ties with his friend like others had. But he wasn’t ready just yet. So he decided to invite Cunningham to a prerelease screening of the film Justice League, and they met beforehand for a talk. He needed to know whether his friend would own up to what he’d done, whether he regretted it, how he wanted to change—and whether, in expressing any of that, he would be genuine and honest.

“My bullshit detectors were on absolute high alert,” he says. “If I'd felt like anything disingenuous was happening, that would have been the end of it.”

What Cunningham said would foreshadow his forthrightness before the court. Nunziata came out of their talk not only believing his longtime friend, but liking and trusting Cunningham more as a person. “If this is what it's taken to rescue Carl, there's a silver lining to it,” he says. “I really think that he's going to come out of this a better person, and actually reset his life.”

The Courtroom

“I just want to make up for it. I have no excuses. Everything that I did was my fault.”

This was Cunningham's plea to Judge Elliot Lee Daum of the Sonoma County Superior Court on November 30, 2017. “I just wish there was something I could do to take away the pain that Steve and the others feel and the shame that I brought on my family for putting them at risk for what I’ve done. I was a good person. I’ve done terrible things to people.”

Cunningham arrived for his sentencing alone. No family, no friends, no girlfriend. He asked them not to come. “He didn’t want to subject any of us to that, nor make it seem as if we were props or a play for sympathy,” says a close family member, who requested anonymity out of fear of further harassment. “It was important to him to face this on his own.”

That would include facing Steve Sansweet.

Sansweet declined to participate in this article through a representative, and has rarely spoken publicly about the events. A few video interviews and one podcast called Rebel Force Radio are rare exceptions:

“We’re not as, I must say, naïve as we used to be," Sansweet told Rebel Force Radio. "Of course when you have somebody you consider a good friend that you’ve known for 20 years decide to steal from you…It’s very difficult to imagine something like that happening…It’s been a rough, rough year because of that.”

The next time the world heard from him was at Cunningham’s sentencing, in a victim-impact statement that revealed the extent of his hurt.

“Carl stole from me under the cover of friendship. He misrepresented his character for the 20 years that I’ve known him and considered him a close and trustworthy friend, leading to my devastating sense of personal loss far beyond the items that were stolen. In my 72 years, in my private and professional life, I have never felt such a sense of betrayal.”

The Rancho Obi-Wan owner expressed no faith in Cunningham’s rehabilitation and encouraged the judge to impose a prison sentence. “I believe he retains the ability to take advantage and deceive even the closest of friends, making himself a continuing threat to society,” Sansweet told the court. “Although he has expressed words of apology, not for one moment do I believe that Carl has truly felt remorse for his actions against me and others.”

Judge Daum sentenced Cunningham to 12 months in Sonoma County Jail, and three years of supervised probation. He also ordered him to pay Sansweet $185,117 in restitution for the stolen items, and Cunningham is also paying back the money he owes Tann.

Cunningham was ready to serve his sentence in a minimum-security facility, but two weeks after his sentencing, the Sonoma County Sheriff’s Department suggested he apply for their “Detention Alternatives” program intended for nonviolent offenders who have expressed remorse. He would wear electronic monitoring and move to California in exchange for avoiding prison. The court agreed.

Cunningham applied and was approved for serving out his sentence under house arrest while equipped with a 24/7 GPS device. Thanks to a system in which he earned two days credit for every two days served, Cunningham spent six months in a California apartment, kept company solely by his dog, a Boxer named Rocky.

Six months' seclusion would have been maddening for some, but Cunningham spent his time reading, writing, and teaching himself Latin. He also finally put Star Wars behind him. “After a brief time of denial, he accepted that part of his life is over,” his close family member tells Popular Mechanics.

Cut off from the outside world, Cunningham returned to his long-dormant Catholic faith and started seeing a therapist over Skype and joined a support support group. His treatment led to uncovering demons—both medical and personal—that Cunningham didn't even know he had.

Slowly, Cunningham was finding his way—but not without heartbreak. One day, while walking Rocky around his apartment building, Cunningham collapsed. A neighbor called 911 and he was hospitalized for 24 hours for dehydration and exhaustion. In August of 2018, shortly after Cunningham finished his sentence and returned home, his beloved Rocky died from a ruptured tumor.

And while Cunningham tried to leave his Star Wars crime behind him, it wouldn't leave him as harassing messages continued. Cunningham tried to accept the hate, but his self-esteem eroded. His family says Cunningham is still working to bolster his self-confidence, and that he chose to continue that work rather than participate in this article.

But maybe the most likely answer as to why Cunningham began stealing comes from unexpectedly losing a job. Because he’d always been one to protect his family from bad news, he was unwilling to ask for help and became desperate. And if losing a job was bad news he couldn’t share, admitting he was stealing rare Star Wars memorabilia would have seemed impossible to admit.

“Then he made a series of really bad, dumb, shameful choices,” his close family member tells PM. “All because he cornered himself.”

But his family believes it's not too late for Cunningham and that, through it all, he's becoming a better person.

The End of the Innocence

No one is allowed in Sansweet's collection alone anymore.

The Jedi master of Star Wars collecting thought about abandoning his museum after the theft. Instead, he installed a new security system and added video surveillance and more personnel to monitor tours. That level of suspicion now exists around nearly all the biggest collections of memorabilia. “I hate to be dramatic and use poetic phrases, but it is kind of a loss of innocence,” says Salvatore.

Zach Tann found himself questioning his years-long passion. He got wary of anything he bought, worrying about the provenance of every item. In the end, Tann carried on for the same reason that drives every collector. “I just can’t stay away from it,” Tann says.

Neither can Sansweet. “The ‘Star Wars’ fan community is such an amazing group of people,” he told The Los Angeles Times in June 2017. “When we first heard about [the theft] we thought, 'What are we doing this for? Why are we working our butts off putting this museum out there for people to see'…But 'Star Wars' fans—there are none better…We’re not letting this one really rotten apple spoil the bunch.”

Star Wars fans wrote to Sansweet, urging him not to let this crime destroy his life's work. One particularly impassioned person put it this way: “Steve, I just want you to continue what you do. You mean a lot to a lot of people all over the world. You are loved by many people.”

That fan was Carl Cunningham, at his sentencing. He added, “Don’t let what I did change that.”

You Might Also Like