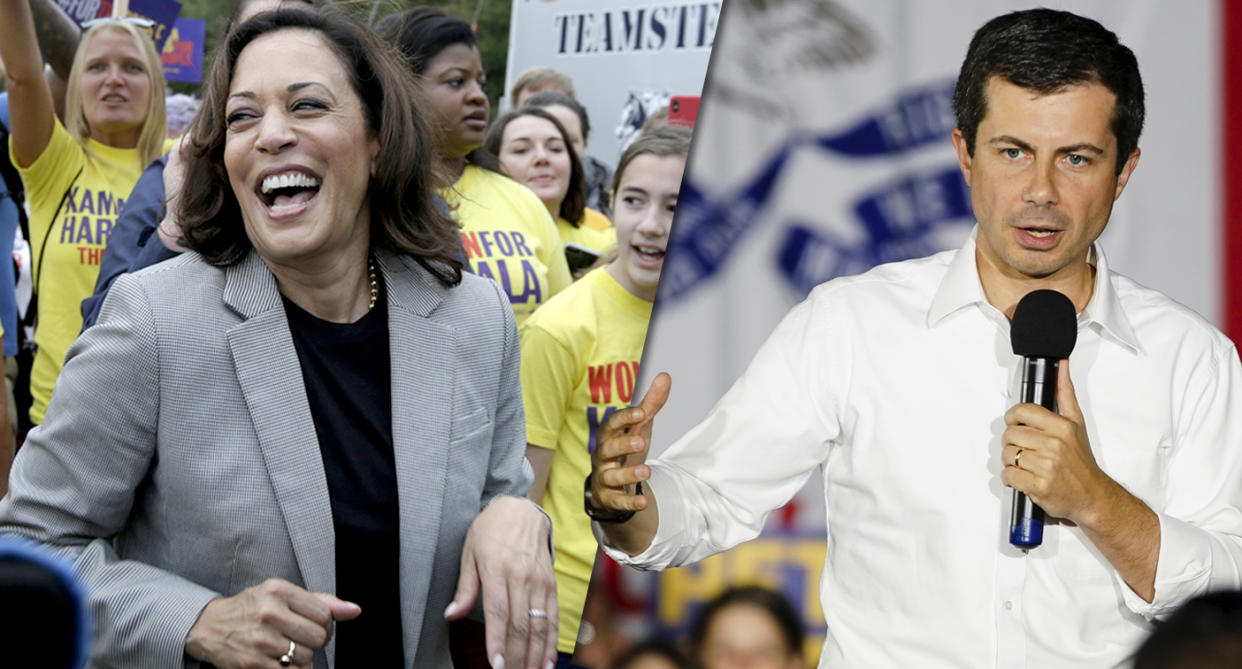

2020 Vision Monday: Harris and Buttigieg are going all in on Iowa. It's a risky bet — but one that has paid off in the past.

Welcome to 2020 Vision, the Yahoo News column covering the presidential race with one key takeaway every weekday and a wrap-up each weekend. Reminder: There are 119 days until the Iowa caucuses and 393 days until the 2020 election.

As usual, Pete Buttigieg said it clearly and crisply. “In order to settle the question of electability, the best thing you can do is perform well in an actual election,” Buttigieg told the New York Times late last month. “Iowa’s of course the first. And so that’s where a lot of our focus is going to go.”

Kamala Harris was a little more blunt. “I’m f***ing moving to Iowa,” she told a fellow senator a few days earlier.

And thus begins the stage of any presidential primary when summer turns to fall, the polling leaders pull away and the would-be also-rans start betting the farm, so to speak, on Iowa. If I can surprise the media with a higher-than-expected finish in the first voting state, the thinking goes, the breathless coverage and renewed momentum will reset my campaign and propel me in New Hampshire, Nevada, South Carolina, Super Tuesday, the nomination, the presidency and a place in American history…

Now, where was I? Oh, right, a diner in Council Bluffs.

There’s even a name for it — the Iowa Strategy. The question now, four months out, is: Can it actually work in 2020?

Buttigieg and Harris are putting that proposition to the test. In September, while attempting to gin up press interest with a freewheeling, everything’s-on-the-record Iowa bus tour modeled on John McCain’s Straight Talk Express, the South Bend, Ind., mayor announced he’d opened 20 field offices and hired nearly 100 staff members statewide, putting his ground game on par with Elizabeth Warren’s and Bernie Sanders’s. His “relational organizing” model — volunteers contact friends and family first, instead of cold-calling strangers — is reportedly yielding a contact (i.e., a pick-up-the-phone) rate of 50 percent, as opposed to the usual 15 percent. He’s pitching himself to rural voters as a fellow Midwesterner — bolder and less insidery than Joe Biden, but not as far left as Warren. And with a $19.1 million third-quarter fundraising haul (third in the field behind Sanders and Warren), he’ll have the cash to keep going.

Harris, meanwhile, started her campaign with a completely different approach: Focus at first on more diverse primaries — South Carolina, Nevada and California — while conserving resources often used in early states for television ads in later ones. But after failing to transform breakout moments into sustained strength in the polls, Harris conceded that any comeback would be dependent on Iowa and soon added another 60 organizers and opened 10 new offices around the state — bringing her current totals to 125 and 17, respectively. In early August, Harris embarked on a five-day Iowa bus tour, her longest retail swing to date, and she’s back this week for a three-day jaunt to the Des Moines area.

Harris and Buttigieg are hardly alone; several even-lower-tier candidates — Amy Klobuchar from neighboring Minnesota; Hawkeye State obsessive John Delaney; Montana Gov. Steve Bullock — are staking their campaigns on some form of the Iowa Strategy.

But Harris and Buttigieg are probably best positioned to capitalize. Though Buttigieg is polling a distant fourth nationally — with 5.5 percent support on average, he’s more than 10 percentage points behind Sanders and roughly 20 points behind Biden and Warren — in Iowa he’s much closer, at 11.3 percent, to the top tier: less than 1 point behind Sanders and about 10 points behind Biden and Warren. For Buttigieg, a finish in the top three isn’t out of the question, especially with Biden struggling to respond to President Trump’s Ukraine onslaught and Sanders (and possibly some voters) shaken by a recent heart attack scare. And those same forces could also boost Harris, who polls just behind Buttigieg nationally and ahead of the rest of the field in Iowa.

History may offer some hope — and a note of caution. Whenever the time finally comes to deploy the Iowa Strategy, campaign staffers always cite two precedents to justify their decision: Jimmy Carter and Barack Obama. In 1976, the self-styled peanut farmer from Plains, Ga. — also the state’s governor — legendarily “came out of nowhere” and catapulted himself to the nomination after upsetting a huge field of more famous Democrats in Iowa. Campaign lore has it that Obama pulled off a similar feat in 2008.

But Carter and Obama didn’t turn to Iowa to save them at the last minute; they had been banking on it all along, and by October, they were already showing signs of front-running strength. In an October 1975 Des Moines Register poll, for instance, Carter won 23 percent of the vote — nearly double the support of his closest rival. And Obama was also polling in the 20s at this point in 2007; from Thanksgiving on, he would lead Hillary Clinton in surveys as often as not.

The better example for Buttigieg and Harris may be John Kerry. It was only at the eleventh hour, after flagging in the national polls and falling behind Howard Dean in the must-win state of New Hampshire, that Kerry went all-in on Iowa in the 2004 race. He emphasized his tried-and-tested electability. He shifted most of his resources to the state. He took out an $850,000 personal loan and mortgaged his Boston home to bring in more money. He unveiled a new stump speech at the state party’s annual dinner in mid-November. And on caucus day, he won with 37.6 percent of the vote.

Asked by exit pollsters why they had settled on Kerry after flirting with Dean, John Edwards and Dick Gephardt, Iowans were clear. More than a quarter said that defeating the despised Republican incumbent, George W. Bush, was their top priority — and 37 percent of those voters chose Kerry.

By contrast, for Democrats in 2020, winning against Trump isn’t everything. It’s the only thing. And that, in turn, may be the only path forward for both Buttigieg and Harris. If they can convince Iowa Democrats to see in them, before anyone else, what they thought they saw in Kerry — their best chance at victory next November — then maybe they’ll live to fight another day.

Download the Yahoo News app to customize your experience.

Read more from Yahoo News:

Greta Thunberg: Powerful men 'want to silence' young climate activists

'I've never had a crystal': Marianne Williamson demands to be taken seriously

Before a notorious phone call, the Trump administration was lauded for helping Ukraine

PHOTOS: New book unveils unique insights from behind the lens of conflict photography