How 2021’s Venice Dance Biennale is Honoring Germaine Acogny, the Mother of Contemporary African Dance

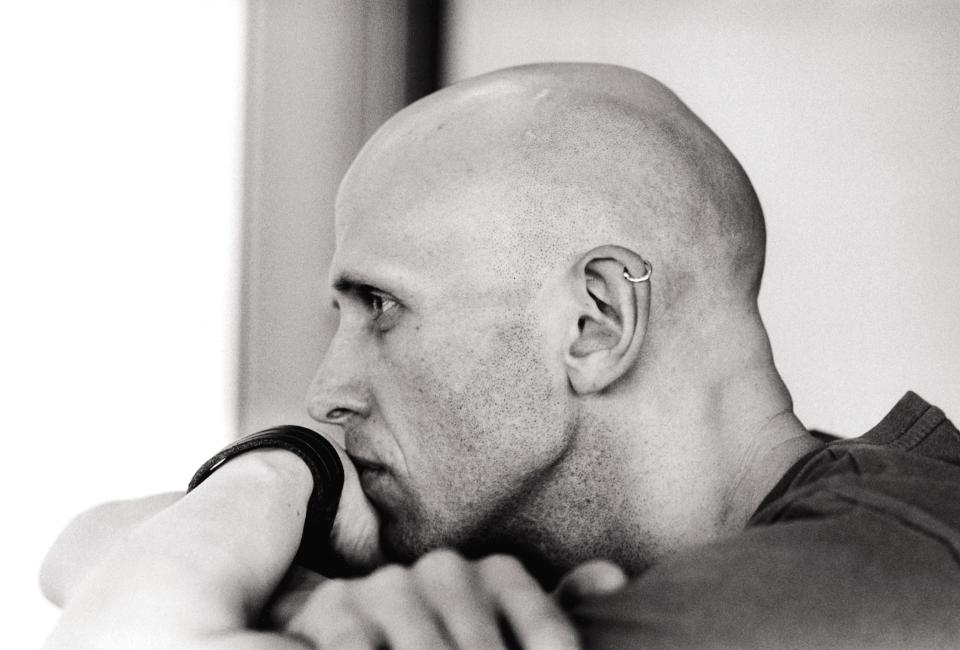

“I'm obsessed with collaboration, and I like to work with different knowledge sets and present dance in a context that is unusual,” says the multi-award-winning British choreographer Wayne McGregor. His approach is one that engages wider audiences in dance, making it accessible to all, and it can be felt throughout the program of the 2021 Venice Dance Biennale, where the 51-year-old is marking his first of four years as director.

Running until August 1, the contemporary festival brings together more than 100 artists from around the world. Russian-American ballet star Mikhail Baryshnikov and Belgian artist Jan Fabre’s film Not Once receives its European premiere, while Random International—the collective behind the installation Rain Room (2012)—and Company Wayne McGregor will present their living sculpture Future Self, with music by German-British composer Max Richter. There is a strong fashion component, too: Daniel Lee of Bottega Veneta, this year’s sponsor, has dressed the Biennale College’s dancers and choreographers.

For 2021, however, the festival’s top honor goes to choreographer Germaine Acogny of Senegal, who receives this year’s Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement. “From [German dancer] Pina Bausch to [Belgian choreographer] Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker, the Dance Biennale has always celebrated women choreographers [since its launch in 1999],” says McGregor. “It’s more important than ever, as organizations are resetting due to the pandemic, that Germaine is recognized for what she has achieved for contemporary dance not just across Africa, but around the world.”

Acogny is a “powerhouse” who is still performing at the age of 77. However, the International Centre for Traditional and Contemporary African Dances—commonly known as the École des Sables, which she established in Toubab Dialaw, Senegal, in 1996—continues to struggle to find essential resources and finances. “It should be supported in the same way as Juilliard [New York’s premier performing arts school],” McGregor adds, “I love Germaine’s work and what she stands for. The Golden Lion is about giving her an even bigger platform.”

Ahead of picking up her accolade and performing her work, Somewhere at the Beginning, at the Biennale, we spoke to Acogny—widely regarded as the mother of contemporary African dance—to hear about her life in motion.

Vogue: Beyond its origin, what makes contemporary African dance unique?

Germaine Acogny: Contemporary African dance takes its energy from the earth. For instance, in my technique, the spine is at the center and it symbolizes the tree of life; the heart is the sun, the pelvis is the stars—every part of the body relates to the cosmos and there is a constant dialogue between the sky and the earth. The idea of linking the body with the cosmos came to me one day when I was watching the moon rising and the sun setting.

You lived in Belgium and France in the 1980s and 1990s, where you worked with the likes of French dancer Maurice Béjart and British musician Peter Gabriel, and established Studio-Ecole-Ballet-Théâtre du 3è Monde in Toulouse with your husband, Helmut Vogt. What did you learn from this time in Europe?

The main thing I noticed was how contemporary artists such as Modigliani and Picasso were inspired by African art, but didn’t always say it; look at Les Demoiselles D’Avignon by Picasso and you can see it is African art. I studied ballet and I based some of my movements on those classical techniques—for instance, I do a grand plié, but with added movement to the spine—just as people come to Africa and get inspired by African dance. There’s nothing wrong with being influenced by other cultures, but you must always acknowledge it.

You returned to Senegal in 1995 and building work on École des Sables was completed in 2004. Why was it important for you to establish an international center for traditional and contemporary African dance in your home country?

My origins in dance were here and it was never my aim to live and die in Europe. I wanted to show it was possible to go and come back to Senegal; that even if you get married to a European as I did, you can bring them with you to Africa and do something here. This is the example I wanted to show younger generations—it is up to us to build our own country.

You created a piece called Fagaala, which is based on the Rwandan genocide, and other work inspired by the poems of Léopold Sédar Senghor, the former president of Senegal. Do you think dance can be a catalyst for political action and social change?

Dance is the mother of all arts through which you can interpret poetry, literature, sculpture, painting—all the arts. It’s a very effective way of communicating without speaking; and it’s a very powerful educational tool, especially around sexuality. Dance can teach us to defend our own space and respect other people’s.

The film of Pina Bausch’s The Rite of Spring—co-produced by École des Sables, the Pina Bausch Foundation, and Sadler’s Wells Theatre London, which starred 38 dancers from 14 African countries—went viral in 2020. What was it about this production that resonated with people and what does it say about the world’s relationship to dance at this time?

When Pina Bausch’s son [Salomon Bausch] proposed we do the piece, my only condition was that it should be [performed] as it was originally—it shouldn’t be different choreography for African dancers. It was well-received because it was the same technique as the European version, but with a different energy. During the pandemic, people have realized how essential the arts are—I hope world leaders start to realize how valuable dance can be for economic development.

Somewhere at the Beginning had its Italian premiere at the Biennale—what are the main ideas and themes explored in the work and how are they expressed through movement?

It’s based on my father’s writing about his life; about colonization, animism, immigration, and his mother who was a Yoruba priest and dancer. My grandmother told my father not to look to Islam or Christianity because we already have everything we need in animism, but he became a Christian, which led to contradictions. For instance, the snake is the main totem in voodoo practice, but it [can be] considered [metaphorically] evil in the Catholic religion. We use videos, music, movement and my voice to tell these personal stories and make them universal—it’s total theatre.

Originally Appeared on Vogue