2023 was a deadly one for Lexington’s pedestrians, bicyclists. Here’s what needs to change. | Opinion

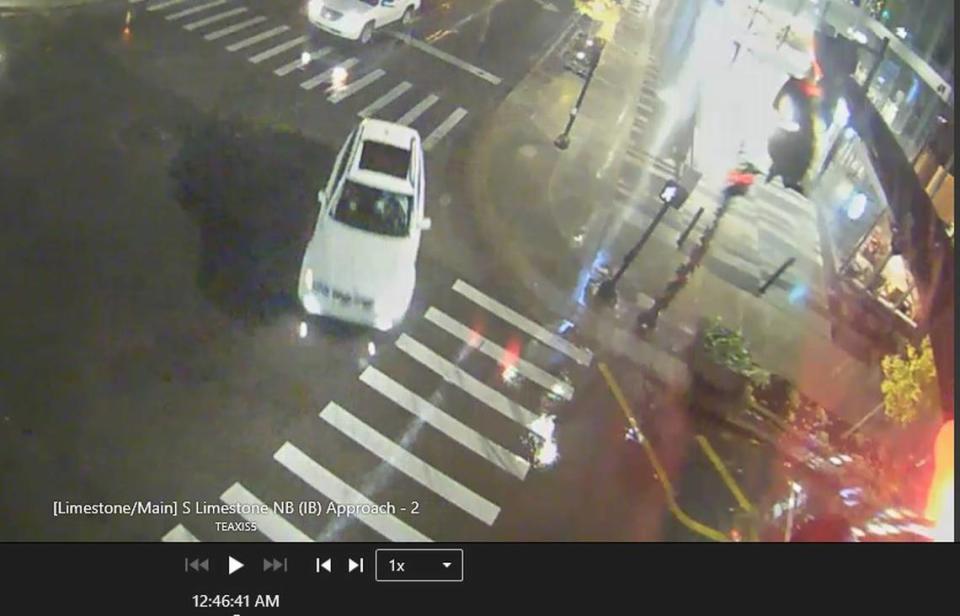

On Wednesday, December 20, a car killed 46-year-old Michael Campbell on his bicycle on South Upper Street. Five days before that, 33-year-old Mia Alayna Ibrahim was killed by a red-light running driver as they crossed Nicholasville Road, about two miles away. Last month, 44-year-old Anna Kolokotsas was killed in a hit-and-run on North Broadway at Fourth Street. Their deaths weeks before the New Year, along with another yet unnamed pedestrian killed on New Circle Road the hours after Christmas, put a cap on what has been an extraordinarily deadly year on our roads: at least 50 people died on roads in Fayette County this year, up from 35 last year and far outstripping deaths from gun violence.

What is happening in Lexington is part of a national trend. Across the country, pedestrian and cyclist deaths are the highest they have been in forty years. Many people instinctively blame smart phones or earbuds, but these devices are ubiquitous throughout the developed world and no other country has experienced a similar increase in road fatalities.

There are multiple factors that have contributed to the increase in road fatalities in the U.S. Three that deserve our attention are vehicle size, hood design, and headlight brightness. Heavier cars, like pickup trucks and SUVs, do exponentially more damage to the people and objects they hit and can kill even at speeds under 25 mph.

While America’s surfeit of large vehicles is often framed as a product of consumer demand, there is more to the story. Before 2008, the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) required car dealers to meet an average fuel-economy standard for their entire fleet. To do this, dealers sold smaller, cheaper, and more fuel-efficient cars at cost to boost the average mpg of their fleet. In 2008, regulations changed so that dealers only had to meet fuel-economy standards on individual cars, judged by weight class. Dealers could then sell a higher proportion of trucks and SUVs so long as those vehicles were considered fuel-efficient for their weight. Dealers have since turned heavily to selling and marketing larger vehicles — on which they earn larger margins — while automakers have phased out smaller cars for US markets.

Hood design also has a major effect on deadliness. Many trucks and SUVs sold in the US would not meet safety standards elsewhere because their “leading edge” (the impact point with pedestrians) is too high. When a high-riding car with a large, flat grill hits a pedestrian, they tend to go under the wheels. When a car with a low, sloping hood hits a pedestrian, they tend to go on top of the hood, increasing their chance at survival. But current U.S. safety standards do not account for safety to people outside the car, unlike much of the world.

A final distinctive aspect of American cars are their headlights. If you’ve driven at night lately, you have noticed that headlights seem brighter now than they did not long ago. This is not your imagination. As halogen bulbs, with their softer yellow light, have been replaced by bright white LEDs, headlights have become brighter, blinding other drivers and pedestrians. Not incidentally, while pedestrian deaths are up overall, they are especially up at night. Again, this is not the case in other countries, which regulate headlight brightness more tightly.

Weight, hood design, and headlight brightness are all regulated at the federal level, for good reason. But local officials are not powerless to intervene, and their power extends beyond victim-blaming reminders to cross at the crosswalk (as Mia Ibrahim did). The most obvious intervention would be to redesign major roads like Nicholasville, Winchester, and Broadway to slow and calm traffic. Other cities, like Washington, D.C., have introduced registration fees pegged to vehicle weight, using higher fees on heavier vehicles to pay for road redesign and maintenance (heavier vehicles also create more potholes). Many states and municipalities also regulate after-market modifications like suspension lifts that raise hood height even further; Kentucky does not. And while driver opposition to speed cameras is intense, where they have been implemented, they have been proven to reduce speeds and deadly collisions. The fines do not need to be large to have an effect: in some countries, cities have used speed cameras to assess modest fines the equivalent of about $5 USD. The simple threat of reprimand is enough to get most drivers to slow down. Speed cameras may also be more equitable and less prone to racial bias than human enforcement.

In both the death of Mia Ibrahim and Michael Campbell, the coroner’s office labeled the crashes accidents and police have said they do not expect charges against either driver. But two otherwise young and healthy people in our community are dead, along with 47 others in 2023 alone. Somebody needs to be accountable. If not the drivers (and to be clear, the drivers should be held accountable), then the city that builds and maintains our roads should be responsible for ensuring our safety. And while efforts are underway to improve road safety, this is a matter of urgency: the cost of inaction or delay is more crashes, more death, and more devastation.

Joseph M.H. Clark is Assistant Professor of History at University of Kentucky.