After 22 years in a South African prison, freedom fighter Denis Goldberg faced an agonizing choice

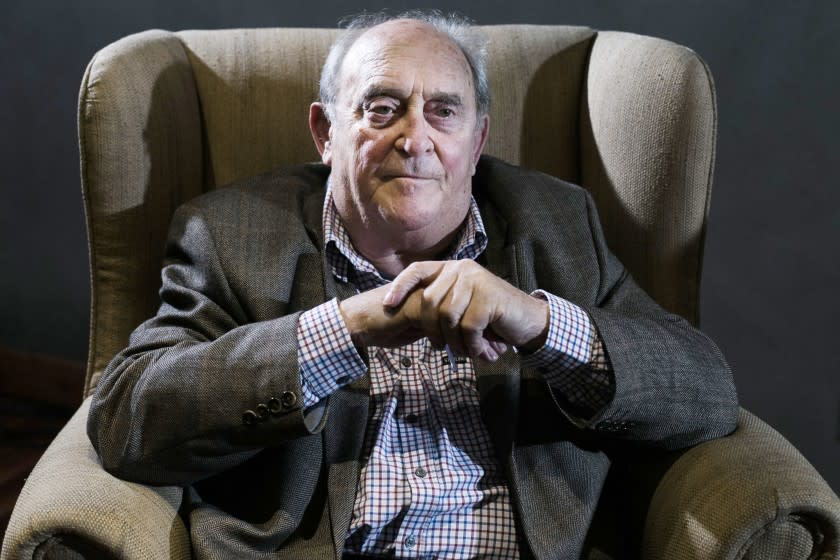

Denis Goldberg, who died recently at age 87, was an early hero of the anti-apartheid movement. A member of the military wing of the African National Congress, he was arrested in a police raid at the group's hideout near Johannesburg in 1963 and prosecuted for sabotage alongside Nelson Mandela. The youngest and only white defendant convicted, he was sentenced to four life terms in prison.

But his obituaries last week largely ignored one of the most fascinating episodes in Goldberg's life, an agonizing moral choice he was forced to make after 22 years behind bars — the kind of enormous, freighted, painful decision that ordinary people are rarely called upon to make outside of movies and novels.

The choice was this: In early 1985, two decades into his prison term, South African authorities came to him with a proposal. They would allow him to leave prison a free man, immediately. But in return he would have to renounce violence.

That may not seem like a very onerous condition, but in the context of the raging liberation struggle being waged by the ANC against racism and white minority rule, it posed a colossal dilemma. Many people — including Goldberg and Mandela — believed that years of nonviolence had failed, and that apartheid could not be defeated without armed struggle; to this day, many historians say the South African government would have endured much longer without it.

Mandela believed so strongly in armed resistance that when he was offered conditional amnesty at the same time as Goldberg, he refused it, opting to remain in Cape Town’s Pollsmoor Prison rather than renounce violence. “I cannot sell my birthright, nor am I prepared to sell the birthright of the people, to be free,” Mandela said in a statement reported around the world.

So Goldberg had to decide: Would he make a sacrifice like the one made by the movement’s leader, or would he secure his own release and reclaim his own life while still in his early 50s?

After "days and nights" of wrestling with the issues, he chose release, becoming the highest profile ANC prisoner to accept the offer. He promised not to plan, instigate or participate in violence for political ends, and, in late February 1985, two weeks after Mandela refused the offer, Goldberg was taken from his whites-only prison to a plane that flew him out of the country. “I hope my comrades understand why I signed,” he told reporters. He also said, “I know this was selfish.” And when asked about those who had refused the offer, he said simply: “I’m not as strong as they are.”

So how are we to view that choice in the light of history? If Mandela's decision was heroic and principled, was Goldberg's a betrayal? Was he "selfish," or merely human? Was he racked later by guilt and self-reproach?

In 2001, Goldberg (no relation) talked to me from London about his thinking. He described his conversion to the anti-apartheid cause as a young communist, his work as a weapons maker (none of his bombs went off, he said) and his arrest at the Liliesleaf farm in Rivonia.

Sent to prison near Pretoria, he said, he lived “under the gallows, literally,” with hangings taking place every week. In the early years, he had to sleep on a thin mat on a hard floor. His barred cell was open to the freezing outdoors. “It’s lonely,” he told me. “There’s no softness in prison, nothing to absorb the banging of steel doors.”

He said he was denied any news of the world for 16 years — no radio, no television, no newspapers. His letters were censored.

He went to prison when his daughter was 8 and his son was 6. They were not allowed to visit for seven years. He told his wife she should see other men, and she did.

Goldberg said he felt that as the sole remaining white prisoner serving a life term, he had become an important symbol of white solidarity with the anti-apartheid struggle. But by the time the amnesty was offered, being a symbol wasn’t enough. He was emotionally weakened, “ragged around the edges.” By the end, he had served 7,904 days.

“I’m not speaking to justify myself. I am trying to tell it as it was. An awful moral choice,” he told me. “I made a choice and I lived with the choice and I got on with my life.”

Goldberg noted that his deal didn’t require him to apologize for his past behavior, and that he continued after his release to work against apartheid, first as a spokesman for the ANC based in London, and later as the founder of an organization working to improve living standards for black South Africans. He forswore violence, but never criticized those who hadn’t. In a 2010 memoir, he said that as he was making his decision, he had received hints from visitors that the ANC leadership would understand and accept his decision to take the amnesty.

“I am a hero to many people,” Goldberg said, adding that ANC leader Oliver Tambo had "greeted me with an embrace" and that he had met with Mandela several times after he became president. But Goldberg acknowledged that when he first got out of prison he was closely cross-examined by the ANC national executive in Lusaka about his controversial decision. Some people understood; some did not.

“Was I right or wrong? I don’t know,” he said. “I think individuals have to do what they can do and I think they should accept their limits. For me, the moral issue is did I fight apartheid? Did I fight it to the limit of my abilities? I say yes.”

Of course, we'd all like to be Nelson Mandela, with the fortitude to always make selfless choices. But most of us are mortals, complicated and often conflicted, generally well-meaning, each with our principles but each with our breaking points too.

Denis Goldberg devoted his life to a righteous cause and made 22 years of heartbreaking sacrifice on its behalf before reaching his breaking point. For that, he is a hero to me.

@Nick_Goldberg