28 deaths, 1 drop zone. How does this California skydiving center stay in business?

Editor's note: Viewing this story in our app? Click here for a better experience on our website.

Francine Francine Turner and her son Tyler sat across from each other in a Mexican restaurant on a sunny Friday in 2016. Over tacos, they chatted about a thrilling adventure he had planned for the next day – one he’d never before undertaken.

Francine Turner and her son Tyler sat across from each other in a Mexican restaurant on a sunny Friday in 2016. Over tacos, they chatted about a thrilling adventure he had planned for the next day – one he’d never before undertaken.

Tyler, 18, and two of his closest friends, Casey Nelson and Mario Muniz, had graduated a few months earlier from Pacheco High School in Los Banos. Mario would turn 18 in less than a week, and the trio decided to mark this milestone with an adrenaline rush:

Skydiving.

Saturday, Aug. 6, was supposed to be the group’s final big celebration of the summer – one last blowout before they began life’s next chapter.

All three were admitted to UC Merced, where Tyler, Casey and Mario planned to move in together. Tyler finished his senior year at Pacheco with a 4.3 GPA and had earned a full-ride academic scholarship from the Central California university.

The conversation between mom and son turned to Saturday’s jump at a skydiving facility near Lodi in San Joaquin County, about a half-hour drive from Sacramento. The two of them kicked around hypotheticals.

“What if the parachute doesn’t open?” Turner recalls them asking, semi-laughing. “Like that’s never gonna happen in a million years.”

Their curiosity grew. So they searched the internet and came across an article on what to do if a parachute doesn’t open.

“It said, ‘Well do this, do that, do this. And then the last thing was: Pray.’”

Who regulates skydiving?

Skydiving is a thrilling but dangerous – and sometimes deadly – activity. The Sacramento Bee has determined that since 1985, a staggering 28 people have died just at this one location outside Lodi, known today as the Parachute Center.

Skydivers there have run into each other in midair. They have had their parachutes malfunction. One dropped over nearby Highway 99 – and was slammed into by a semi-truck.

Others have escaped mid-air mishaps, but not without serious injuries.

A Bee investigation examined the situation, framed by trying to answer specific questions: How does a place where at least 28 people have died stay in business? And what more can, or should, be done to prevent fatalities?

The answers are complicated, but largely come down to this: Despite the inherent danger, skydiving is for the most part unregulated.

The Federal Aviation Administration regulates airplanes and pilots, but not the businesses and generally not the activity.

The agency has issued more than $900,000 in penalties for various issues related to aircraft used by the Parachute Center. But William Dause, the center’s founder and face of the business, who at 80 years old continues to fly skydiving planes there, said he hasn’t paid them.

The FAA also requires that tandem instructors be licensed, but it makes no effort to ensure compliance other than issuing fines after the fact.

California regulates any number of businesses and requires professional licenses, including for nail salons and car washes. But no state agency regulates skydiving.

Local government – in this case the San Joaquin County Board of Supervisors – has the authority to set rules for business licenses, but has not taken action to restrict the center’s operations.

The United States Parachute Association, an industry organization, has taken action against Dause, revoking his individual membership. But there is no requirement from any state or federal agency that the center be a member of the USPA.

Then there are the courts. Dause has been successfully sued for $40 million. But no victim can collect from a person who on paper claims he has no real assets.

In addition, the Parachute Center and other such operators benefit from another compelling factor: Humankind’s often eyes-wide-open willingness to take risks in a quest for thrills.

So, despite the danger and the deaths, despite revoked memberships, and despite millions of dollars owed from fines, liens and a civil judgment, business here continues.

The planes keep flying. The jumpers keep dropping.

A successful skydive

PHASE 1

Into the Blue

Before you jump, it's crucial to assess the environment, ensure a safe drop zone, make sure there are suitable wind speeds, and find out if you’re medically fit to do so. Once you reach about 12,500 feet, a pilot will signal for you to begin your descent.

PHASE 2

The Free-fall Experience

In free fall, a person can hit 120 mph. Symmetrical hand and foot positioning is vital for control. Deploying the parachute too soon risks loss of control, entanglement, and drifting off course.

PHASE 3

Deploying the Parachute

At 5,500 feet, get ready to deploy the parachute, ideally around 4,500 feet. Regular equipment checks are vital. Twists and hard openings can lead to injury. In extreme cases, a cutaway may be needed to free a malfunctioning main chute and use the reserve.

PHASE 4

Navigating the Canopy

After your canopy is deployed, you will descend for about 4-6 minutes. During this time, your speed will slow down from 120 mph to approximately 17 mph, depending on the canopy size. Actively control and steer your parachute to avoid roads, power lines, and trees.

PHASE 5

The Final Descent

When approaching the landing zone, fly into the wind at a height of 200-300 feet. Once you're in the zone, position your canopy so it reduces your speed and aim to touch down at a speed of 0-5 mph. Even minor errors below 200 feet can be fatal. It's crucial to maintain unwavering focus.

embedInfographic.style.marginBottom = "0px";

Arriving at the Parachute Center

The morning of Aug. 6, 2016, Turner drove Tyler and Casey from Los Banos to the Parachute Center.

The business is based at Lodi Airport, a privately owned and managed strip with two runways in Acampo just a few hundred feet west of heavily-trafficked Highway 99.

The drop zone greets visitors with signs just off a frontage road. They read “SKYDIVE,” with red arrows pointing to a hangar.

The building is one of about a half-dozen hangars near the runways. It has been frequented by experienced recreational jumpers and newbies. The center has drawn visitors from across Northern California and beyond, including skydivers from such places as Europe, Asia and South America.

“It wasn’t run down, but it didn’t look very professional,” Casey recalled. “It didn’t look welcoming.”

Tyler and Casey planned to meet at the drop zone that morning with the two other party members – soon-to-be birthday boy Mario Muniz and his cousin, Quinan Muniz, also 17 – along with Mario’s mother and other family members, who came along to watch and sign waivers for the juvenile jumpers.

Tyler likely felt at least somewhat nervous about skydiving, said Casey, who had known him since first grade. Tyler rarely showed those nerves outwardly, but Casey said it was the type of thing a best friend could sense.

Tyler spent a chunk of the 90-minute car ride to the drop zone making a purchase on his phone.

The teen loved video games. He and his friends were partial to a popular fighting game series, Super Smash Bros. The group held a series of competitions called Smash Tour, of which Tyler was founder and president.

Smash Tour crowned the winners with a pro wrestling-style “title belt” made out of paper.

On the way to Acampo, Tyler ordered a new belt through Amazon. He wanted the tradition to continue even as he and some of his pals moved away to different colleges.

The Parachute Center opened at 9 a.m. The Muniz birthday group was there for the first flight of the day.

They walked into the hangar and paid the skydiving fee, spending extra for the experience to be captured on video.

The boys sat down on benches – like “church pews,” Turner recalled – and started to watch a safety video.

“In the middle of the safety video – which is on a reel so you kind of jump in wherever – they hand you a clipboard with a release,” Turner said. “How can you fill that out and watch the safety video and be successful at both? You can’t.”

Mario said the safety video had only been on for about 2 minutes when one of the workers at the Parachute Center started to gather their waiver forms and lead them away to gear up.

“We were nowhere near the end of it.”

In a September interview with The Bee, Dause noted the video is about 20 minutes long. He said the viewing of it could be cut short.

“Traditionally, it doesn’t happen,” he said. “I’m pretty adamant about making sure they watch the video.”

The staff started strapping the jumpers into their parachute equipment, Casey recalled, and explained that they would be connected to their corresponding tandem instructors.

Tyler was paired up with Yong Kwon, a 25-year-old from South Korea.

The group exited the hangar out of a side door and made its way toward the plane: a de Havilland “Twin Otter,” which Turner said carried Tyler’s group along with more than a dozen others for about 18 total jumpers.

“That’s when he went and knelt down,” she said, “and said his prayer.” Turner keeps a photo of the moment in a scrapbook in her living room.

After he prayed, Tyler gave a brief interview to a videographer.

“That’s my mom over there,” he said in the video. “Very loving mom. Done a lot for me in my life. Hope more that she’ll help me with more of my life, ‘cause I want to make it.

“We’re gonna make it.”

Tyler high-fived the videographer. He walked over to his mom.

“I love you, mom,” Turner recalled him saying. “Gave me a big hug and then went and got on the plane.

“That’s the last time I saw him, touched him, smelled him, heard him.”

How many skydiving deaths? No one knows

There is no official number for how many people die skydiving each year – because no federal agency requires deaths to be reported or bothers to keep track.

The United States Parachute Association does keep its own tally. From 1985 through 2022, it calculated the fatality rate for skydiving to be just under one death per 100,000 jumps.

The USPA uses an estimate of jumps made by association members and its best guess of the total number of skydiving deaths in the country to arrive at that figure, according to Ron Bell, the organization’s director of safety and training.

The Parachute Center is not a member of the USPA, nor has it ever been.

As such, it’s difficult to put the 28 deaths at the Parachute Center into meaningful context. Dause, the center’s longtime but now former owner, has repeatedly stated that he does not know how many jumps occurred at the site.

“I have no idea. We have never, ever tracked them,” Dause told The Bee, “or even tried to track them.”

When pressed, Dause did note that at its height — pre-pandemic — the Parachute Center ran as many as about eight planes, some of which could carry about 20 people each.

Using the organization’s fatality rate, the Parachute Center would have needed to average about 78,000 jumps per year – or roughly 214 jumps a day – over those 38 years to achieve a death rate equal to the association’s average.

The USPA said four affiliated drop zones reported at least that many annual jumps in 2022, with the busiest coming in at just over 112,000. The average center, however, tallied fewer than 16,000 a year. Those figures are based on a survey in which about one-third of USPA-member centers reported their total numbers, according to Bell.

Jim Crouch, the USPA’s former safety and training director, said in an email that without knowing the number of jumps at the Parachute Center, it was hard to compare it with other skydiving businesses across the country. But he said he could not “recall any other large and busy skydiving center with that many fatalities since 1985.”

The Bee contacted 10 other skydiving centers in Northern and Central California and the Lake Tahoe area of Nevada. All but one either declined to disclose both their fatality and jump numbers or did not respond to requests to do so.

Tyler Wareham, owner of NorCal Skydiving in Sonoma County, said no one had died at the business since it opened around 2009 and that it handles roughly 2,500-5,000 jumps a year.

SkyDance SkyDiving at the Yolo County Airport is the closest skydiving facility to Sacramento. The Bee has reported at least nine fatalities there since 1989. The center opened in 1987. A representative for the business, which is a USPA member, was among those who declined to comment for this story.

Bottom line: Without stronger regulatory oversight that would require an accurate count of deaths and jumps, it’s difficult to say just how dangerous skydiving is – or whether the Parachute Center is an outlier warranting any particular enforcement action.

The FAA certifies planes and pilots. And there are rules for how parachutes are supposed to be prepared before jumps occur. For example, a reserve parachute must be packed by a certified specialist and be used within a specific number of days, based on its material.

That said, federal officials don’t track or license skydiving businesses. There is also no set of federal or state safety standards those centers must follow.

The FAA’s limited role in skydiving is especially apparent after someone dies. Agency investigators don’t try to determine what caused the fatality other than to check if certain factors, including the condition of the plane or an action by a pilot, played a role.

“They’re pretty basic,” Ed Scott, the former executive director of the USPA, said about the agency’s investigations.

The federal government, by default, relies on the USPA to develop best practices for the sport. Its members pledge to follow the association’s basic safety requirements. They are also supposed to file incident reports with the USPA when a skydiver dies or requires medical attention due to an injury, or has equipment malfunction during a jump. Those reports are made public but the locations of the incidents are kept confidential.

Membership, however, is voluntary, and the USPA has no real authority other than to revoke or suspend ratings, licenses and memberships that it issues.

The manner in which skydiving businesses are regulated has long concerned the National Transportation Safety Board, another federal agency. In 2008, the NTSB, which doesn’t regulate skydiving, called the FAA’s oversight “inadequate to ensure that operators are properly maintaining their aircraft and safely conducting operations.”

In 2019, a skydiving plane crashed in Hawaii. All 11 people on board died. Following an investigation, the NTSB issued a report that said concerns with skydiving operations remained unresolved. An aggressive takeoff maneuver by the pilot likely caused the crash, the agency determined. But it pointed to other contributors. The “FAA’s insufficient regulatory framework for overseeing parachute jump operations” was one of them.

It urged the aviation agency to come up with national safety standards, or equivalent regulations, for skydiving operators, and those of other airborne activities.

Kathryn Thomson, the FAA’s deputy administrator, in August reported the agency was considering changes that may address the NTSB’s concerns.

Even though the FAA’s oversight of skydiving might be viewed as lax, it does take action — and it has done so against the Parachute Center.

In the early 2010s, the agency slapped the business with two separate penalties, totaling more than $930,000, for not following safety rules for aircraft. In one case, the FAA said the center flew a plane more than 2,000 times while it was overdue for replacement parts and out of compliance with inspection rules.

Still, the aviation agency was unable to settle the cases and referred them to federal prosecutors, who found Dause had relied on the word of a mechanic, according to an FAA report. Prosecutors concluded that meant Dause would likely win a legal challenge.

The report further noted that prosecutors also determined Dause only had a minimal amount of documented assets to even pay off any judgment won in court. Dause told The Bee he has not paid the fines.

No further action was taken. The flights and the jumps continued.

Lauren Horwood, a public information officer for the U.S. Attorney’s Office in Sacramento, declined to comment on the status of the cases.

The USPA also has tried to intervene. While it can’t regulate the business directly, it can offer some oversight of its members – including those who served as tandem instructors at the Parachute Center.

In 2016, the association determined that people who attended tandem instructor training courses at the center were not properly taught or certified.

One of those was Yong Kwon.

Tyler would have had no reason to suspect that his tandem instructor might not have been qualified. Then, again, neither would the FAA nor any other potential regulatory agency.

The FAA only learned of the problem after the fact. The type of oversight that might have prevented Kwon from being up in the air that day – making life-or-death decisions – simply does not exist.

High fives. But where is Tyler?

Turner sat outside on a couch in Acampo, leaning back and staring up toward a plane.

She watched the Twin Otter climb in circles, spiraling up until it reached its target altitude of 13,000 feet.

Casey and Mario recalled the moments before the jump.

“Before I hopped out, I looked behind me, and I just said, ‘I’ll see you later,’ Casey said, referring to Tyler. “Gave him a thumbs up.”

Mario sat directly behind Tyler.

“We’re in there. Super hard to hear. Really loud,” Mario recalled. “Tyler was sitting right in front of me. … They’re like, ‘All right everyone. We’re ready to jump.’ Tyler throws the peace sign, gets ready to jump out.

“And that’s the last time I ever saw him.”

Mario did see what he thought was Tyler’s parachute. About a minute into the jump, though, he lost sight of his friend.

Turner watched as specks departed the plane, each expanding with a “poof” about halfway to the ground as the parachutes deployed.

Casey and the Muniz cousins landed in the field.

“We run up to each other,” Mario said, “start hugging, high-fiving each other.

“Then it was, ‘Hey, anyone know where Tyler landed at?’ That was when our hearts all kind of sunk.”

Waiting for Tyler to walk in from the field, Turner didn’t look for her son’s face, too difficult to spot from afar, or even his clothing.

She instead looked for Tyler’s distinctive gait, defined by a slight drag of his right foot brought on by a mild case of cerebral palsy.

Casey walked in from the field.

The two cousins walked in from the field.

Tyler didn’t.

Turner assumed that her son changed his mind.

“I said, ‘He chickened out, didn’t he? He didn’t jump.’ And Casey goes, ‘No, he jumped.’

“So where is he?”

Then the videographer emerged from the landing zone.

“He looked petrified. He had just a look on his face. I don’t know how to describe it. Disbelief, maybe. And he didn’t speak English very well. So I said, ‘Where’s Tyler?’ And he goes, ‘Um, uh…’ He didn’t really say anything.”

Turner ran inside the lobby. The videographer, who had made it inside first, was saying something to Dause and others working there.

Within moments, staff at the drop zone began looking at a big map pinned to the wall, scanning the terrain. Some of them jumped in cars and pickup trucks.

A search began.

State fines center, but not because of deaths

In addition to the FAA and USPA, other entities have at various times probed the activities of the Parachute Center and tried to hold it accountable.

In 2010, state labor inspectors walked into the skydiving center on a summer day and found a group of people helping customers inside.

Dause said the people there were not employees, according to a summary of a disciplinary appeal. Instead, he considered them independent contractors. But a hearing officer later disagreed and determined some should be covered with workers’ compensation insurance.

The officer issued an $8,000 fine.

In 2012, labor officials returned to the center. Dause again called the people working there independent contractors, not employees, according to a summary related to a separate appeal.

He said they had their own businesses, brought in their own customers and handled their own advertising, the summary said. He claimed he did not control their working conditions, only the number of customers that boarded each plane.

Another hearing officer disagreed with Dause, saying he erred by not providing itemized wage statements to 42 people at the center.

The officer issued a $10,500 fine.

Both penalties were paid, according to a public information officer for the state Department of Industrial Relations.

That hasn’t always been the case.

At the time of a 2020 deposition, Dause said he had a judgment on his home, joking he was “borrowing it from the state.”

What caused the judgment is unclear. Dause, in a separate deposition, said it was filed by the state Employment Development Department. He and the parachute business have faced more than $2.3 million combined in tax liens from the EDD since 2014, records show. The agency declined to provide an update on the status of the liens, citing confidentiality rules.

Dause told The Bee in September: “I owe the state $2 million.”

Other scrutiny has come after fatal incidents.

Following a string of them at the Parachute Center in the early 2000s, a colleague asked then-Sgt. Bill Isaacs to look into what was going on.

Isaacs worked in the coroner’s division, which was then within the San Joaquin County Sheriff’s Office. The office was concerned about what was going on and people had complained to the agency, Isaacs recalled in a May interview with The Bee.

The Sheriff’s Office contacted the FAA, he said, and Isaacs found out about the federal agency’s limited approach when it came to examining skydiving fatalities.

“It didn’t go anywhere,” Isaacs said of his investigation.

A mom’s frantic search

Turner jumped in her car and followed one of the Parachute Center workers – the only one she could catch up to – as they began to scan the territory near the landing area.

They arrived at the gate of an Acampo grape vineyard, part of Robert Mondavi’s Woodbridge Winery and one of many in the surrounding area, exited their vehicles and searched on foot.

“We ran through the dirt … and it’s soft dirt, so it’s almost like walking in snow or sand,” she said. “And I’m panicking, and looking, and yelling for him. The guy who I had followed, I lost him. And so I kind of ended up by myself, and I didn’t know where I was, in the middle of these vineyards.”

Turner was lost. Exhausted. Though the terrain evoked snow, a warm August day started to take hold.

When she finally emerged from the vineyard’s trenches, she spied a set of railroad tracks. They would give her a better vantage point, gather her bearings and find her son.

Winded from traversing the peaks and troughs of the vineyard, she struggled her way up a gravel embankment toward the tracks.

“I got to the top, out of breath, and I turn and I look, and I see fire trucks, ambulances, sheriff’s (deputies), police, all of this going on … OK, I’ve gotta get over there.

“Because I have to see what’s wrong with my son.”

Turner ran back through the field, trudging again through the dirt.

She tried to flag down an incoming ambulance for a ride. It didn’t stop.

When she finally made it to the scene, a deputy with the San Joaquin County Sheriff’s Office halted her.

The first 911 call to the Sheriff’s Office came at exactly 10 a.m. Deputy Joshua Turner was dispatched two minutes later to a vineyard near East Peltier Road in Acampo.

A vineyard field worker and his foreman directed Deputy Turner down a pair of dirt roads, a couple of hundred yards away from M2 Wines, and about a mile from where Casey and the Muniz cousins landed.

The workers pointed the deputy to a row of grapevines. There he came upon two bodies on the ground attached to a parachute backpack and harness, “with obvious signs of death,” the deputy wrote in a report.

Both were prone, face down, with Kwon atop Tyler.

A field worker, using the foreman as an interpreter, told Deputy Turner that he and other field workers heard a “loud flapping noise” from above, then looked up and saw the duo “coming down at a very high rate of speed.”

The field worker said that their parachute “did not appear to be open, but (he) saw strings in the air.” He “heard and saw them hit the ground,” then checked on them. They were motionless.

A deputy on scene asked Turner for her son’s ID.

“He took his driver’s license, and it seemed like forever, and he came back and said, ‘I’m sorry to tell you, he’s not alive.’”

Later, Turner recalled something she’d seen earlier in the day from the couch while watching the boys jump. With the knowledge of her son’s death, she now understood what she had witnessed.

“It looked like the shape of a pencil.”

At the time, she thought to herself, “That’s odd. I wonder what that is.”

Now, she knows. It was Tyler and his tandem instructor.

Many deaths and many causes

Of the 28 deaths identified by The Bee, Tyler and Kwon weren’t the only ones that died on the same day.

In September 2009, parachutes used by Barbara Cuddy, 48, and Robert Bigley, 32, became entangled. The experienced skydivers were part of a group practicing a diamond-like formation in the air. Their chutes deflated as they fell to the earth.

Entanglements were just one of the suspected causes of fatal incidents. Midair collisions, equipment problems and even suicide were some of the others.

Based on The Bee’s review of county death investigations, as well as FAA incident reports and news accounts, 10 of the deaths fell broadly under the umbrella of equipment issues – parachutes or related mechanisms not functioning properly.

At least eight other deaths, including those of Cuddy and Bigley, involved entangled parachutes – between those of multiple jumpers, with a piece of equipment or between the main and reserve chutes of single or, in the case of Tyler and Kwon, tandem jumpers.

In three additional fatalities, jumpers collided with other skydivers or a parachute canopy in midair.

Two others involved procedural issues as the jumpers approached the ground: a landing problem in one case and a skydiver turning too low in another.

Authorities suspected suicide in two of the deaths. In two other cases, skydivers apparently never pulled their parachutes for unknown reasons.

And in one instance, a 52-year-old man reportedly suffered a heart attack while falling.

Dause said he doesn’t keep track himself, but said there have been “20-some” fatalities at the Parachute Center. He contends that at least three deaths, and possibly as many as five, were suicides.

As for the fatal incidents overall, Dause said: “There isn’t anything I could have done different that would have changed the outcome. Yes, I could have not opened up this place. I could have stayed home. I could still be on the farm in Utah.”

The most recent death at the Parachute Center occurred in 2021. Sabrina Call, 57, was also an experienced skydiver when her main and emergency parachutes nosedived underneath her during her descent, according to a county death investigation. Sheriff’s deputies said it was her fifth jump of the day.

Witnesses say William Calhoun III’s parachute appeared to deploy properly in 2012 as he dropped from the sky, according to a county death investigation. But the 71-year-old veteran jumper began to spiral out of control, and he was unable to steady himself before landing in a nearby vineyard. An FAA inspector found no evidence that Calhoun deployed his backup parachute, the county’s report said.

Maria Robledo Vallejo’s death stands out for another reason. Vallejo, 28, had been staying at the skydiving center for about two weeks when she jumped with a group of seven others, a county death investigation found. It was not uncommon for skydivers to camp at the center.

Vallejo had no entanglements, no failure of the chute to deploy. But just as she was about to land, wind apparently blew her parachute off course. And right over nearby Highway 99 – directly into the path of a semi-truck. The impact sent her tumbling roughly 60 feet away.

“I witnessed that. I’ve witnessed most all of them,” Dause said, “and it’s still sad.”

While the Parachute Center’s death total might very well be an outlier, it is far from the only drop zone that has witnessed tragedy.

The Bee discovered that one only has to go as far as Southern California to find another skydiving operation with a large number of fatalities.

More than 20 people have died at Skydive Perris since 2000, according to newspaper reports and data from the Riverside County Sheriff’s Office.

Skydive Perris is a member of the parachute association and its general manager, Dan Brodsky-Chenfeld, is a safety advocate. He survived a 1992 plane crash at Perris Valley Airport that killed 16 others, most of whom were skydivers. In a 2020 video for the parachute association, he urged fellow skydivers to not underestimate the risk of a jump and overestimate their readiness for one.

“It’s a dangerous sport that can be done safely,” he told The Bee.

Brodsky-Chenfeld said centers can provide a safe environment for jumpers and not have a fatality for years. Then, without changing anything, they could have several fatal incidents over a short period of time. Jumpers can become complacent or make mistakes.

When asked about the deaths at the Parachute Center, Brodsky-Chenfeld said he didn’t think that number alone made a statement about the business.

“There are many things that are beyond the skydiving centers’ control.”

The array of potential causes of death poses a challenge for anyone trying to regulate the sport. There is no one solution to prevent all of the things that can go fatally wrong.

Investigators face another challenge: The people who often know the most about what happened have died.

Two deaths — and back to business

Francine Turner can never know for certain what her son said or thought as he fell.

He was a devout Christian who listened to an audio version of the Bible every single night as he drifted to sleep, including on the eve of his death. Turner said Tyler almost certainly prayed – just as he had done before telling her he loved her outside the hangar, just as the internet article they read at the Mexican restaurant had suggested.

In the scrapbook dedicated to his memory, a pair of angel wings is superimposed over the photo of Tyler kneeling in prayer outside the Parachute Center.

That is the last picture Turner has of her son. To this day, she has never seen any images of Tyler’s body after the fall.

“I never wanna know,” she said. “I just don’t.”

By the time Tyler’s body was found, Turner’s brother, her middle son Troy and her then-boyfriend had arrived as authorities continued to investigate – and as planes continued to fly, dropping more jumpers overhead.

“I look up,” Casey recalled, “and there’s just another one of those skydiving planes just going by.

“Like, business as usual. People didn’t even seem to care that not only one of my best friends had died, but also one of their fellow employees.”

Dause said he understands that concern, but argued that pausing jumps “wouldn’t have made any difference.”

“Stopping this place would not have brought them back to life. Stopping what’s going on would have only irritated a bunch of other people,” he said, referring to other skydivers waiting to jump. “Do the other people matter?”

Dause compared the business-as-usual approach to a vehicle crash on the highway. “Somebody gets killed in a wreck out there, the other lane is still open. Cars are still going by.”

The car crash analogy disgusts Casey.

“Uncaring is an understatement,” he said. “It’s vile.”

The closest Turner came to seeing her son after his death was long after he fell. The coroner’s van was driving away with her son’s remains.

“I asked them to stop,” she said. “And we put our hands on the recovery vehicle – it’s a big white van – and they stopped, and we all said prayers. And we let it go. I put my face against it, and I was looking through, and I could see the body bags in there.

“That almost was too much.”

It would be the last time she saw her son’s body. It would not be the last time she would deal with the Parachute Center or its founder.

The Parachute Center’s founder and face: William Dause

William Dause opened the parachute business in 1981.

By then, he was considered one of the most experienced skydivers in the United States. He had jumped around 7,500 times and spent several dozen hours in free fall, according to a story from the time in a magazine put out by the USPA. Dause also had previously run drop zones in other locations, including in Utah, where he said he grew up.

A thin man with tan arms and white hair down to the back of his neck, Dause claims now to have made more than 31,000 jumps in his life. He said he started skydiving when he was 21, while he was in the Army, and became hooked after three jumps.

Over the years the center he started has attracted patrons who also became hooked. Stacy Hinson was one of those committed regulars.

Starting in the mid-1990s, Hinson would wake up early on weekend mornings and drive to the center from Fremont. Sapped from his day job as an electrical foreman, he found relaxation slicing through the sky.

“All the stress just flowed out with the wind,” Hinson said in a recent interview.

In 2001, he was attempting to glide over a small body of water at the Parachute Center, a technique called “pond swooping.” But he landed wrong, crashing into the ground. He hit his head, causing a brain bleed. His hip crumpled. His ankle shattered. His shin snapped. Vertebrae broke in his back.

After 54 weeks of recovery, Hinson went right back to doing one of the things he loved most: He went to the Parachute Center and jumped out of a plane.

“It was an outlet for me,” he said. Hinson continued skydiving there regularly before becoming a father in 2004.

Reflecting on his nearly fatal fall, Hinson, 58, blames himself for what happened. It was his decision, his “screw up.” As for Dause, Hinson remembers him as being “very safety conscious” and a “savvy businessman.”

Despite having such devoted followers – often drawn to the center’s low prices – Dause claimed financial troubles were a common issue. In 2020, he was asked in a deposition the last time the center made a profit. His response: “Probably close to 30 years.”

Still, records show the center saw significant business in some years. In 2014 and 2015, for example, it had more than $2 million in gross sales or receipts each year, according to tax documents obtained by The Bee. Nevertheless, the business operated at a loss those years, the records show.

Rental costs played a major role. Dause, in a deposition, said renting planes was probably the center’s biggest expense. The business also leased its parachutes.

“When I owned the business, every penny went back into the business,” Dause told The Bee. “I upgraded my airplanes, I got bigger airplanes. I got more airplanes.”

Dause said he later gave up those planes as a way to pay for bills. The center leased them from the same company to which he sold them, he said in a deposition.

Dause also claimed that he didn’t receive a salary from the business or derive any income from it.

He doesn’t “need a lot,” he told The Bee. Much of his current wardrobe, he said, is made up of “neglects,” – clothing skydivers leave behind at the center.

When asked in a deposition how he survived over the years, Dause answered: “By doing what I had to do.”

What it appears Dause didn’t do was keep meticulous records related to the skydiving activity at the center. And that went beyond stating publicly that he didn’t keep track of how many jumps were actually performed there.

Deputy Matt Renz interviewed Dause following the deaths of Tyler and Kwon. He asked for a flight manifest.

Dause did not have one, according to the deputy’s report. Instead, he “provided (Renz) with a piece of paper that did not have the specific plane number,” though Dause later gave the deputy the pilot’s name and plane number. The sheet, however, did not have a list of passenger names.

The closest thing Dause had to an accounting of the passengers was their signed waivers. He handed Tyler’s to Renz.

Dause informed the deputy that Kwon was not an employee of the center but that Kwon had shown him instructor certification paperwork. As such, Dause allowed him to run paid tandem jumps there.

Kwon’s certification status, though, would later be central to a civil lawsuit filed by Tyler’s parents – as well as a separate criminal investigation.

A civil suit and criminal charges

Everything was going well when Kwon and Tyler first jumped out of the plane, about 13,000 feet above the ground. But an FAA inspector later found Kwon ultimately made fatal choices as the two continued to fall.

For some reason, he did not deploy his main parachute. Later, after dropping roughly 10,000 feet, Kwon attempted to disconnect the main chute and deploy an emergency one, footage from the videographer showed. The two parachutes tangled, preventing the backup chute from fully inflating.

Kwon was out of options. He and Tyler plummeted the remaining few thousand feet, smashing the ground at more than 100 mph.

Following the fatal jump, the FAA investigation found more issues. Although Dause provided documentation that showed Kwon had received training, he was not yet properly certified to conduct the tandem jump, as is required under federal law. He was also supposed to have successfully completed a tandem instructor course.

Kwon had attended a tandem course at the Parachute Center before the jump. But one of the people who signed off on his training, Robert Pooley, had a suspended instructor rating with the USPA. Another was out of the country at the time of the training, but that instructor’s signature nonetheless appeared on paperwork, the FAA investigation found.

The USPA, as a result of its own investigation, required roughly 140 people who attended tandem courses at the center, and others, to undergo additional training. The FAA took no action.

“I certainly felt there was potential for harm to the reputation of skydiving and the association, which is why we took that, you might say, rather large action and took it quickly,” said Scott, the USPA’s executive director at the time. Less than a month after Tyler and Kwon died, the association revoked the memberships of both Dause and Pooley, along with any licenses and instructor ratings they held, according to Bell, the USPA’s safety and training director.

Federal prosecutors later accused Pooley of using pre-filled forms showing the other instructor’s signature and of concealing his past suspension from students. They charged Pooley in 2021 with aggravated identity theft and wire fraud.

Pooley has pleaded not guilty, and his case is set to go to trial in May.

In an email, federal public defender Heather Williams said none of the charges against Pooley alleged that he caused Tyler and Kwon to die. Williams said she believes prosecutors chose to indict Pooley because he “was the only person they could figure out how to charge with any crime.”

Horwood, of the Sacramento U.S. Attorney’s Office, declined to comment and said prosecutors on the case also would not comment.

Dause, in a deposition, said he told Pooley to “pack his bags and leave” the Parachute Center on the day Kwon and Tyler died. Days after the incident, Dause sent a letter to the USPA saying: “None of the trainees were directly or indirectly involved with me other than I may have given some of them USPA forms for licenses or membership.”

When the FAA completed its review of the incident, it determined it could not prove any violations of federal aviation regulations had occurred. The U.S. Department of Transportation’s Office of Inspector General opened a complaint against Dause in 2016, according to an FAA report. A public affairs official for the office declined to comment on its status.

In 2018, Turner and Tyler’s father filed a civil lawsuit against Dause and Skydivers Guild Inc., the company running the center at the time of their son’s deaths.

During the case, the attorney representing Skydivers Guild dropped it as a client, court records show, because it didn’t have money to pay him.

Dause did not hire another lawyer to represent the company, despite San Joaquin County Judge Barbara Kronlund’s repeated warnings about doing so. In California civil suits, companies cannot represent themselves in court. Only a licensed attorney may do so.

“The Parachute Center, nor I, had nothing to do with it,” Dause told The Bee, referring to Tyler’s death.

In March of 2021, Kronlund issued a $40 million judgment against Skydivers Guild. The judge said Dause was responsible for the entire amount.

Judgment issued, but not paid

Winning a lawsuit and collecting a judgment are two decidedly different realities.

Attorney Paul Van Der Walde represented Tyler’s parents in the lawsuit.

“I was pretty confident that he was bringing in enough money to make the case viable,” Van Der Walde told The Bee, “and I could get some redress for them.”

In the midst of the case, Van Der Walde grew concerned that Dause was playing a shell game with companies to avoid financial accountability.

Dause said the Parachute Center has operated under multiple corporations, each with a different legal name. The center currently is run by a company called Acme Aviation Inc. Although Skydivers Guild was in control when Tyler died, by the time the Turners sued Dause a year and a half later a company called Skydiver Services Inc. ran it.

Dause was an officer in some of the earlier corporations, including Skydiver Services, but he said he’s not formally affiliated with Acme Aviation.

“I don’t own any part of the corporation,” he said. “I have no (financial) interest in the corporation. I am not getting paid by the corporation.”

Van Der Walde is concerned that money from the business was hidden or skimmed.

“The way this has been able to keep going on is, he keeps opening new corporations,” Van Der Walde said, “using the same equipment, using the same planes.”

Dause called the changing of legal names “normal business practice,” decisions made for reputational reasons and not monetary ones and on the advice of an attorney.

“There’s no assets to hide, no money to hide.”

As part of the case, though, Kronlund noted Dause had a pattern and practice of avoiding creditors.

The ruling lasts for 10 years but can be extended. If Dause, who will turn 81 in February, dies while the judgment is unpaid, it could remain open after his death. Dause said he has no children.

Shortly after the judgment, Dause’s formal, legal ties to the Parachute Center ended.

Richard Smith, an experienced skydiver, had heard about the judgment and spoke with Dause about keeping the center alive, he said in a 2022 deposition. Smith, 39, skydived at the center and said he had known Dause for more than a decade.

“I knew that the business was just going to go down,” he said. “So I came in there, and I just took over the leases.”

Smith, who is the president of Acme Aviation, said he did not pay Dause when the corporation took over the Parachute Center. Dause said he told Smith: “It’s yours.”

Dause told The Bee that Smith lives in Nevada and comes to the center “occasionally.”

More involved than Smith, Dause said, is Robert Pooley – the same man facing federal charges for the findings unearthed after the deadly 2016 jump.

Pooley shoots video of drops and also does “some instruction,” Dause said.

When reached by phone, Pooley declined to comment.

Van Der Walde isn’t convinced much has actually changed since the new entity took over: “I think it’s the same operation.”

To his point, a handout titled “Acme Aviation Inc.” was available in the Parachute Center lobby when reporters visited in September. On the same document, the center is also called by one of its former legal names, Skydiver Services – which, the handout said, has been “serving the sport since 1964.” Skydiver Services was not incorporated in California until 2017. Dause dissolved the corporation in 2021, the year Acme Aviation was formed in Nevada, state business records show.

Smith did not respond to efforts to reach him directly or through family.

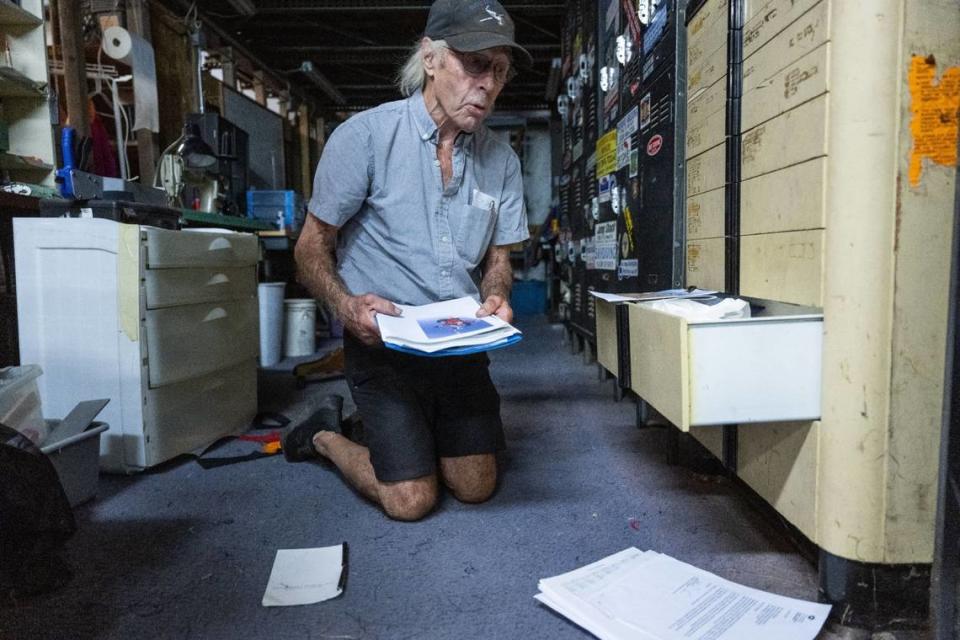

Regardless, Dause clearly remains involved in the center’s operations. He was working behind the counter, answering calls and handling payments in September. He said he’s there every day, calling himself the “janitor” when first asked for his title.

One of his biggest roles these days? Flying planes. The drop zone’s “main pilot” died of cancer about a year ago, so Dause said he took over the cockpit.

“I think volunteering would probably be the best term to use. I’m here because I want to be.”

Or, as Dause put it in a 2021 deposition: “Working is not the right word to use. I’m playing.”

Playing, but not paying.

More than two years after the judgment, Dause said he has not paid any of the $40 million, which is growing due to accrued interest, according to court records. He does not intend to pay any of it either.

He has claimed Social Security payments are his only form of income. That money is generally exempt from being seized to pay off a judgment.

If he had started paying, Turner knows what she would have done with the money, at least back then.

“Buy a giant bulldozer and just bulldoze the crap out of it,” she recalled thinking. “I would have loved, at the time, to see the place shut down.”

Local officials show concern, but take no action

Putting the Parachute Center out of business is clearly easier said than done.

The business has survived the almost $1 million in penalties from the FAA. It has survived the scrutiny of state labor officials and the fines and liens that followed. It has survived a local probe by law enforcement and a criminal investigation by the federal government. It has survived a $40 million civil judgment.

And it has survived being that place – the place where at least 28 people have died.

Skydiving, Dause acknowledged, is a risky activity. To some degree, that’s the whole point.

“People are after a thrill. The thrill has to be, or have, some risk involved in it.”

Talking about the day Tyler and Kwon fell to their deaths, Dause even appeared to speak positively of the impression it may have left on skydivers there waiting to jump.

“That’s part of the mystique, the drama, the challenge – the overcoming your fear – that people do,” he said of keeping the center open that day. “‘Oh, someone died.’”

The deaths have prompted some local officials to take notice over the years. There was particular interest following the deaths of Tyler and Kwon.

Former San Joaquin County Supervisor Chuck Winn represented the Lodi area at that time. In an interview, Winn said he and other county officials looked into what could be done after they died.

Their final decision: to take no action.

“There wasn’t anything we could do,” Winn said.

The county granted a business license to the center. Under its rules, licenses can be revoked, but only if the person applying for it has been convicted of a crime related to the person’s business.

That wouldn’t have applied to the Parachute Center.

But perhaps it would if the supervisors wanted it to. The rules for county business licenses are dictated by local officials. And they vary widely in California.

Some counties don’t require businesses in unincorporated areas to be licensed. Others, such as San Joaquin County, do. More importantly, some that do have more ways to take away a business license than San Joaquin County.

In Yolo County, for example, it can happen if a business or activity is hazardous to public health, welfare or safety, due to a change in circumstances and conditions. It can also happen if a court determines a business has caused or become a public nuisance.

Sacramento County officials can revoke a license under several circumstances, including if the business is a repeated nuisance or is found to be a safety hazard to people nearby.

Asked if he and other San Joaquin County officials considered changing county rules to take action against the center, Winn replied: “To be honest, I’m not sure we were looking for ways to create something unique.”

He said the decision not to act was a collective effort that also involved the county’s administrator and attorney.

Monica Nino, who was the county administrator at the time, did not respond to requests for comment by phone and email. Nino became the top administrator in Contra Costa County. Mark Myles, who was then the county attorney, said he did not “have any recollections of any discussions related to the skydiving center.”

Jack Sieglock represented the Lodi area as a county supervisor from 1999 to 2006. During that time, seven people died at the center.

“It never came up,” when asked if supervisors ever considered taking away the center’s license. “We never had to broach the subject.”

Remembering Tyler

Turner no longer wishes to bulldoze the place where her son died.

“I’ve changed my view a little bit,” she said, “just to have somebody run it that knows what they’re doing and do it properly, so that people can enjoy the sport without such a risk.”

A degree of risk will always be present. It’s the nature of the activity. But without strong regulatory oversight, some of the onus for reducing risk falls on the skydiver.

But even then, there is not much one can do other than follow instructions. One can check to ensure the facility is a USPA member, which might provide some measure of comfort. The USPA suggests that those interested in skydiving check out the facility — in person — before proceeding.

Turner understands that people want to engage in an adrenaline-packed activity. She doesn’t want to see that go away.

Her anger is directed at Dause, not skydiving.

“They cut corners, and they did so many things that they shouldn’t have done, that I feel 100%, Tyler’s death could have been spared, and many of the others.”

The Bee asked Dause what could have been done differently to prevent the two young men from dying.

His response:

“Well, she couldn’t have got pregnant,” he said, presumably of Tyler’s mother. “He could’ve gone to a different school. He could’ve had different friends. There’s a thousand things. I could’ve not existed. But the fact of the matter is, people die. Whether it’s their fault or someone else’s fault, they die. Everybody’s going to die...

“Are there things you can do to prevent that? Yes. Stay home.”

When asked to narrow in on the fatal jump itself, Dause said that “absolutely nothing could have been done differently.”

One of the occasions Turner spoke to The Bee was on Feb. 25. It was Tyler’s birthday.

A tribute to Tyler sits over the fireplace in Turner’s living room.

Crosses, flowers, candles, ribbons and the teen’s smiling senior portrait rest on the mantle and hang on the surrounding wall.

On the hearth sit two pairs of Tyler’s shoes: a white pair of high-tops from his early childhood, and a dark pair of Vans.

The dark gray shoes are the only article of clothing Turner kept from his final day.

Even after she moved to a different home in Los Banos, she also kept the big, brown worn down couch her son would sit on as he played video games with his brothers and friends.

She grieved for a month straight on that couch.

“I was in a fog.”

Amid that fog, a sharp reminder of Turner’s loss literally arrived at her doorstep.

It was an Amazon package.

Inside of it: the paper wrestling belt Tyler had ordered on the car ride to the Parachute Center.

His mom keeps a different paper belt, one signed by Tyler’s friends, in a glass display case in her kitchen.

For Turner, it’s a reminder of just how many people came to love him in a lifetime cut tragically short.

Later that afternoon, she drove to Los Banos Cemetery.

Tyler shares a plot with a cousin who was killed in 2000 at age 8 in a freak accident. Matthew Nathanael Salazar died after being struck in the head accidentally by a golf backswing.

Matthew’s parents now live in Idaho and will be buried there, so they offered their piece of the plot for Tyler. His headstone is to the left of Matthew’s.

Turner placed a bundle of birthday balloons – mostly purple, her son’s favorite color – beside Tyler’s grave.

“Beloved son, brother, grandson, uncle, nephew, cousin & friend,” Tyler’s headstone reads, followed by a Bible verse, Matthew 19:26: “Jesus looked at them and said, with man this is impossible, but with God all things are possible.”

Turner kissed her hand, then pressed it to the photo of Tyler, in his smiling senior portrait, that adorns his gravestone.

She told him she loved him. Then she wished him a happy birthday.

Tyler Turner would have been 25.

The Bee’s Phillip Reese contributed to this story.

Why did we report this story?

Following the $40 million civil court ruling in March 2021 against William Dause and the Parachute Center’s 28th reported death in April 2021, Sacramento Bee journalists endeavored to find out how the high-profile Northern California business has managed to stay open – with Dause still the public face of the operation while owing tens of millions of dollars to the family of Tyler Turner who died there in 2016, at age 18.

How did we report this story?

Reporters Michael McGough and Stephen Hobbs spent months combing through court filings, depositions and a federal indictment; Federal Aviation Administration and National Transportation Safety Board records, reports and citations; airplane registration databases; county business records; California business license information; archived stories from multiple news publications spanning several decades; and anonymized data provided by the United States Parachute Association.

The reporting led to a complicated conclusion: Without stronger regulatory oversight, it’s difficult to say whether the Parachute Center is an outlier warranting any particular enforcement action.

Still, it is clear Dause has continued to play an active role at the drop zone more than two years after a judge ordered him responsible for the eight-figure sum. Dause said he has not paid any of the debt and does not intend to. When reporters visited in September, he was working behind the Parachute Center's front desk and as a pilot. At the same time, he said he no longer has formal, legal ties to the business, which he founded in 1981.

Who did we talk to?

The Bee interviewed Dause at the Parachute Center and Francine Turner, Tyler's mother, at her Los Banos home. Those conversations were focused on the deaths of Tyler and his tandem instructor Yong Kwon but also delved into the appeal of skydiving, a recreational activity that is adrenaline-pumping but inherently dangerous.

The Bee also interviewed a range of experts, skydivers, attorneys and government officials, as well as loved ones of Tyler.

Credits

Michael McGough | Reporter

Stephen Hobbs | Reporter

Hector Amezuca | Visual Journalist

Lezlie Sterling | Visual Journalist

Alvie Lindsay | Editor

Sohail Al-Jamea | Art direction & animation

Rachel Handley | Illustrations & Design

Gabby McCall | Page Design

David Newcomb | Development & Design