32% of Michigan toddlers at risk for preventable diseases as vaccination rates fall

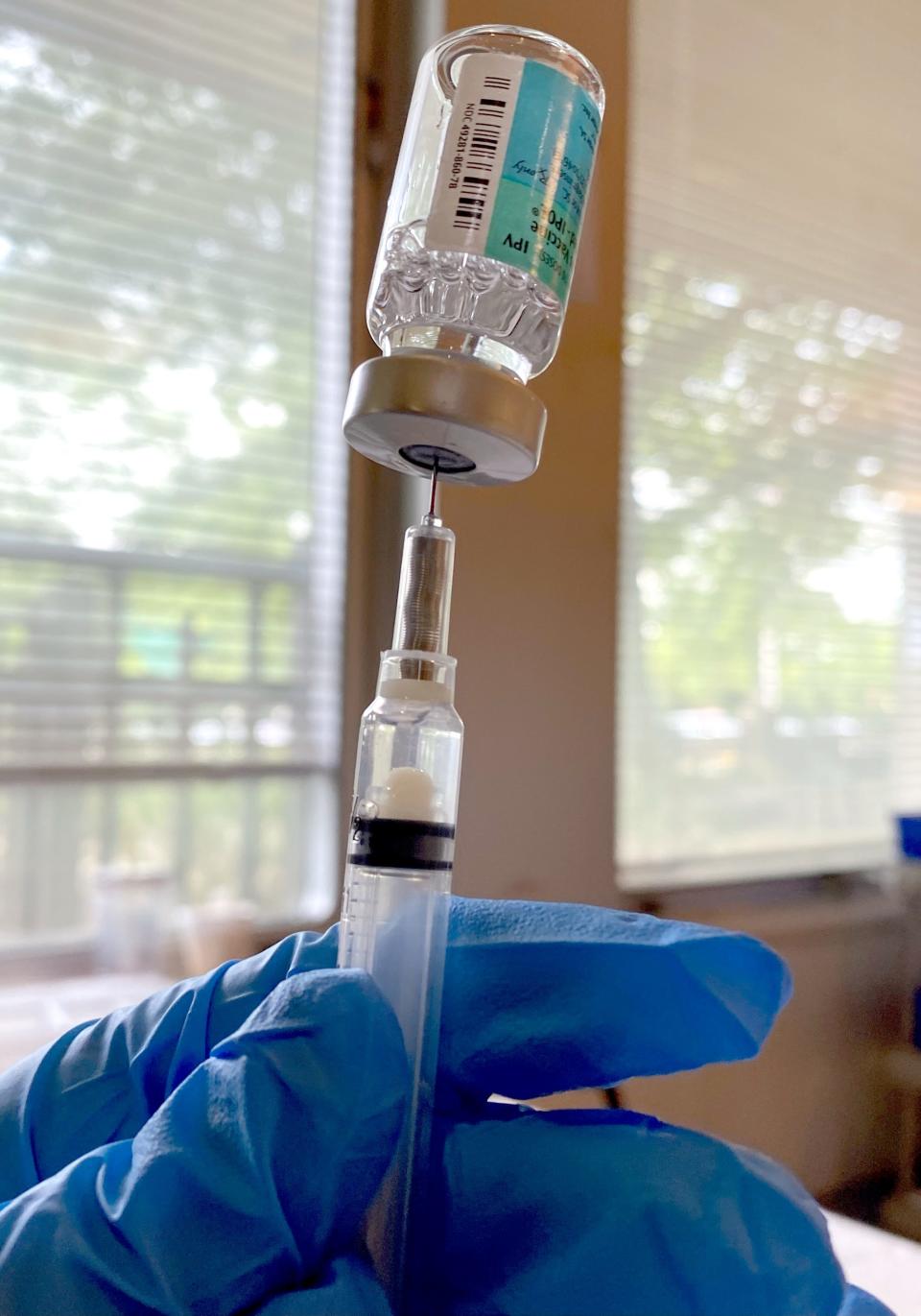

The Michigan Academy of Family Physicians sounded the alarm Monday about falling vaccination rates for preventable childhood diseases such as measles, polio and whooping cough, since the start of the coronavirus pandemic.

"We have seen a 6% drop in toddler vaccinations in Michigan over the past two years, which is alarming," said Dr. Delicia Pruitt, medical director of the Saginaw County Health Department. "As it currently stands, 32% of Michigan toddlers are at risk for preventable disease because their immunizations are not up to date.

"For children of color, children living in poverty, and those who are uninsured and are covered by Medicaid, these rates are even lower. This makes the disparities in health outcomes among segments of our communities even greater."

Pandemic interrupted regular doctor visits

The problem began, she said, with the pandemic.

"People weren't able to visit their primary care physicians for in-person appointments for things like immunizations," said Pruitt, who also is a family physician in Saginaw and an associate professor at Central Michigan University's College of Medicine.

"But now we can connect in person again and it is time and it's overdue for us to do everything we can to protect our children and the most vulnerable in our communities against preventable disease by getting caught up on our immunizations."

Overall coverage for the primary childhood vaccine series in Michigan, which includes vaccines that prevent measles, mumps, rubella, tetanus, diphtheria, pertussis, haemophilus influenzae, hepatitis, polio, chickenpox and pneumonia, fell to 68.5% in the first quarter of 2022. That's about a 6.5% drop since July 2019, according to the state Department of Health and Human Services.

More: Study: About 7,300 lives saved by COVID-19 vaccine mandates on college campuses

More: Children under 5 start receiving Covid vaccines

Among adolescents in Michigan, coverage of state-recommended vaccines has fallen to 72.9% over the same time period — about 4 percentage points, according to state data.

While it might not seem like much of a dip, Dr. Glenn Dregansky, president of the Michigan Academy of Family Physicians, said every case is important.

"Without the protection of vaccines, illnesses such as measles, whooping cough, COVID-19, and even seasonal flu can easily spread," Dregansky said.

Measles is so contagious, for every person who has it, up to nine out of 10 people around them will get measles if not fully vaccinated, Pruitt said.

"The virus causing measles results in fever and rash and in most serious cases brain swelling, which can lead to permanent brain damage and death, she said.

Whooping cough, also known as pertussis, is equally contagious "and a significant threat to babies," Pruitt said. "Without proper vaccination, data shows that half of the babies infected with pertussis end up in the hospital and one out of every 100 infected babies dies. Children who are not vaccinated against the disease are eight times more likely to get pertussis than children who receive all recommended vaccine doses."

'We have to overcome that fear' of vaccinations

Misinformation, particularly on social media, has made an already growing vaccine hesitancy problem worse in the U.S. and eroded trust in government institutions, Dregansky said.

"Parents are afraid to immunize in some ways because they're worried that it'll hurt their baby," he said. "The worst thing that ever could happen to a parent is if something happened to their babies.

"We have to overcome that fear. That's why the relationship, the longitudinal relationship that family physicians have, and pediatricians have, over time helps allay that fear. So that's one of the ways we get over the fear."

People who don't have trusted relationships with a primary care physician may not have a dependable resource for vaccine information, he said, and too many parents today don't know about how devastating many of these diseases can be.

"People aren't afraid of the ... vaccine-preventable illnesses because we haven't had huge outbreaks in decades," he said.

"When I was in training ... about every other month, we lost a baby or a young child to bacterial meningitis that is utterly preventable now because the vaccines are so efficient. So in some ways, we're victims of how good we've been at this. And so now it's been two generations and the parents don't have the fear of these diseases. So it's really difficult to overcome that."

Worry about polio reemerging

He is especially concerned about polio, which was thought to be eradicated in U.S. But last month, a person from Rockland County, New York, was the first to contract the virus in a decade in the United States. Polio has been detected in wastewater samples dating to early June in Rockland County, suggesting the virus may be spreading among unvaccinated people.

"We should be extremely concerned," Dregansky said, noting that there are few treatments for these diseases once a person is sickened by them.

"If a child gets polio, there's nothing we can do to prevent paralysis," he said. "Now, most people get polio don't get catastrophic illness, but we don't know why some people do. We don't know why some people get catastrophic illness with COVID. So prevention is the key."

Dregansky, who was born in 1953, said he remembers his grandmother crying when he and his brother were immunized for polio.

"She was so afraid that her grandsons would be crippled like other children," he said. "She watched children crippled and die from polio. The worst thing about polio is if it didn't kill you, it cripples your spinal cord and then you end up on a ventilator the rest of your life or you end up with all of these complications.

"I've treated post-polio syndrome. It's a terrible, painful illness. So my parents and my grandparents literally were joyful at the advent of vaccines because they had such a fear of the disease.

More: Child tax credit helped Michigan kids — and numbers prove it

More: Royal Oak mom shocked by newborn's parechovirus diagnosis: 'I've never heard of this'

"Because we don't fear these diseases, it's inevitable. If you don't know history, it will repeat. And that's the phase we're in now. ... The window (to act) is now. If we don't get going on immunizations, there will be outbreaks."

The vaccination rate isn't high enough in Michigan for people to be protected by herd immunity if there were to be an outbreak of most of these vaccine-preventable childhood diseases, Dregansky said.

"I don't know that we have, frankly, any herd immunity anymore because of this trend toward people not getting immunized," he said. "For herd immunity, it depends on disease. Some diseases, 80-85% of the population needs to be immune. For other diseases, like measles, it's over 90%. And we're not there."

Dr. Beena Nagapalla, medical director for community health at Ascension Southeast Michigan, urged parents to make sure their children are up to date on all their vaccines.

"As immunization rates drop, especially among children, the health of our communities is put at risk," she said. "Now is the time to reverse this trend before it has disastrous results."

Contact Kristen Shamus: kshamus@free press.com. Follow her on Twitter @kristenshamus.

This article originally appeared on Detroit Free Press: Michigan's childhood vaccination rates fall 6.5% since 2019