36 Hours With Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez

Here’s what it’s like to be Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, the most famous regular person on Capitol Hill.

Everyone is talking about her, whether she knows it or not. First, there are the two Wall Street guys in button-downs having coffee in Union Station. “I was so fucking mad when I saw that tweet,” one says.

Later there’s the young woman working the cash register at Au Bon Pain, who says, “She used to be a bartender!” after the congresswoman buys a sandwich.

Then she gets into an elevator with Mike Johnson, her colleague from Louisiana, and his family. “Alexandria,” he says, “just so you know, they were more excited to meet you than any of my colleagues.”

And still, when she heads to the House to introduce her amendment to an appropriations bill (which will pass), a security guard stops her at the door, missing her member pin that would let him know she’s not an intern, or a staffer. “Can I help you?” he asks.

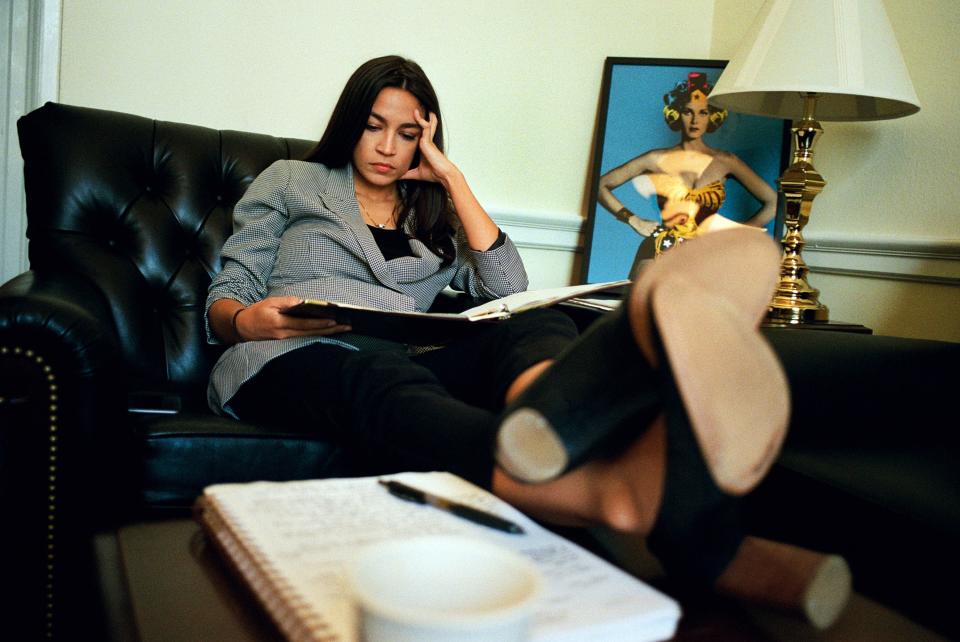

Ocasio-Cortez has been navigating this double life since she won her Democratic primary against Joe Crowley on June 26, 2018, the last time I saw her. It’s been exactly one year. “It feels like it’s been 45,” she says, when we catch up a week before the anniversary. “I am an old woman”—though, sitting in wood-paneled Capitol Hill rooms where portraits of largely old, even dead men hang on the walls, Ocasio-Cortez is remarkably youthful. She looks well-rested, especially for someone who stays up making impassioned statements of moral outrage (and tweets at Chrissy Teigen about garlic-peeling methods). And she has amassed a robust collection of rented designer blazers since I last saw her.

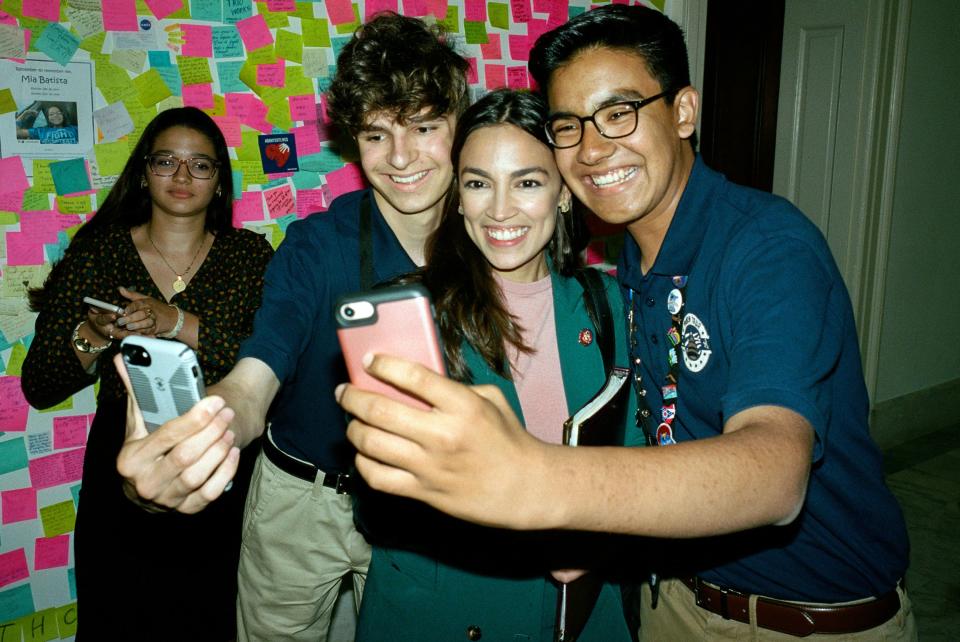

The 29-year-old has brought a different color palette and an eagerness to the usual proceedings that has shifted the stale air here. Walking with Ocasio-Cortez through throngs of admirers and selfie-requesters in Congress is like spending the day with Cardi B, if Cardi B were a democratic socialist (she kind of already is). But in terms of House hierarchy, she’s just a freshman from the Bronx. She does not belong. At the same time, it feels like she’s taken over the place.

We’re meeting after a particularly late night, during which Ocasio-Cortez was building a piece of IKEA furniture while talking to her followers on Instagram Live. By morning, her use of the term “concentration camps” to describe detention centers holding migrants at the U.S. border has created a media conflagration, one that will last through the three days I spend with her. We will both eventually appear together on CNN, one of us more camera-ready than the other. But before that, when I first walk into her office, she’s tweeting back at Liz Cheney about her comments (whom she pointedly calls Elizabeth Cheney, so as not to seem flippant). She’s typing so placidly on her phone, however, that I have no idea it’s happening.

Ocasio-Cortez is known for her pithy “dunking” on Twitter, but she says this confidence was hard won. Last June, Ocasio-Cortez herself thought that digs from critics who watched her steamroll Crowley (at the time the fourth-most powerful Democrat in the House), as a bartender, might prove correct, that she would be a flash in the pan. She recalls when Senator Claire McCaskill described her as “a bright shiny new object.” “I felt that way,” she admits. Even three months ago, she says, “I would have been terrified” of saying what she said about conditions at the border. She would have agonized over whether she had “compromised the movement.” Now, she trusts her instincts more. “It’s rooted in faith that if I vocalize what I think is the morally correct position, people will crop up and support it.” Her staff members do not control her personal accounts; they sometimes find out what she’s said by whether or not it’s trending on Twitter the next day.

The adjustment to her crazy life over the last year has been, in some ways, about scaling back. “The first three months or so of my term were just emotionally exhausting, like I was worried sick every single day,” she says. It was the worst around February and March: She and Ed Markey in the Senate were introducing Green New Deal legislation, a complicated rollout met with mockery from the GOP. She was working late at night to build bridges during contentious debates in the Democratic Party regarding anti-Semitism and Islamophobia. She had to learn to schedule rest time for herself, even if it made her feel guilty. “It was like pure exhaustion. I would go 12 hours without eating.”

Things are smoother now. AOC has mandated paper agendas for every meeting. On the docket for the day is a trip-planning session with her staff: She has been courted by socialists in France, Jeremy Corbyn in the U.K., and the Labour Party in Germany, per Corbin Trent, her communications director. She can do it, she says, but “I can’t be killed, like, every single day.” How to pay for travel is tricky for a politician who refuses to take corporate donations. “Most people just get a really wealthy person,” explains her chief of staff, Saikat Chakrabarti, which is of course, for this group, a joke.

There is a kind of millennial Scooby Gang quality to the AOC Hill staff. Some came over from her grassroots campaign, powered by the insurgent left-pushing PAC, Justice Democrats. None are older than 40; one is 21; another is a prolific Juuler. Occasionally, Ocasio-Cortez looks back down at her phone, “taking a peek at which validators [she] can amplify,” (also known as retweeting).

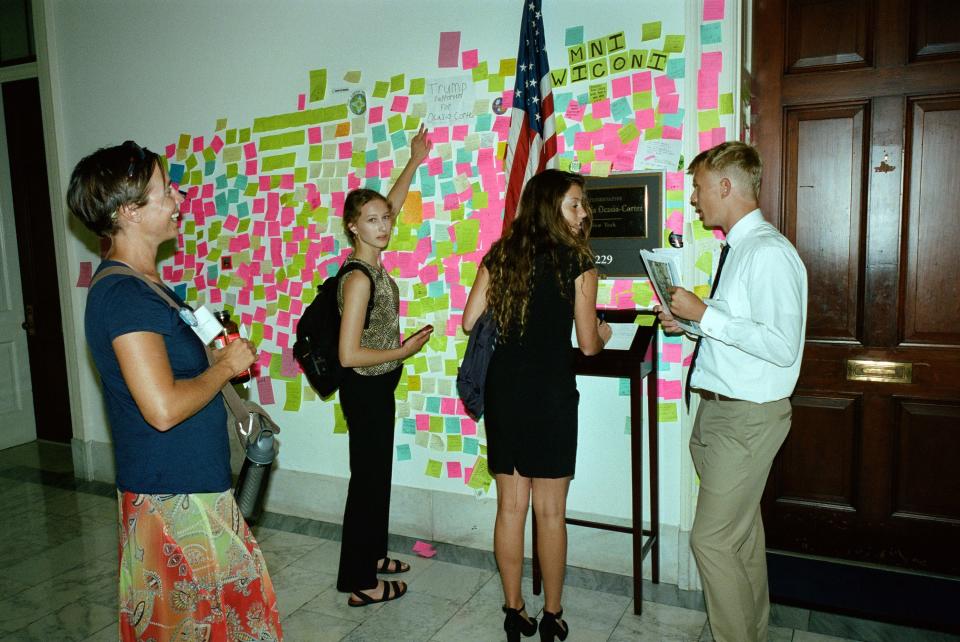

Next, Ocasio-Cortez greets fellowship recipients from Sunrise Movement, the youth climate activist group, one of whom is installed in her office as an intern. She poses with them for a picture in the hallway in front of her office, which is festooned with colored Post-its showing messages of support. People are there, either leaving Post-its or reading them, nearly all day.

A week after she was officially elected, Ocasio-Cortez joined Sunrise protestors in a sit-in in Nancy Pelosi’s office last November. “I didn't know how that was going to play out,” she says. A few months later, Pelosi referred in an interview to the Green New Deal as “the green dream or whatever.” Did it make Ocasio-Cortez reconsider her approach? No, she says. “There would be no ‘green dream’ conversation [if we didn’t do that]. There would be no comment to the press. There would be no attempts to tamp us down or marginalize us or make us seem smaller than we are if we didn’t do the big bold, scary things.”

She understands why her methods are frowned upon by certain establishment members. “In the historic rules of Congress, no one ever cares about freshmen. It’s like high school. . .The prevailing wisdom has always been, ‘Keep your head low, make inroads in leadership. Wait your turn. There are 230-odd members in this caucus. You’re last in line,’” she says. “But the world doesn’t have two decades to wait for climate change to be a palatable, first-priority, urgent issue.”

The next day I can tell that Ocasio-Cortez is approaching by the cheers I hear from the hallway outside the Oversight and Reform Committee hearing, not usually a raucous event. Ta-Nehisi Coates is next door testifying on reparations for a House Judiciary subcommittee, and somewhere else in a closed-off room, Hope Hicks is saying very little.

The other newsmaker of the day is the congresswoman from New York. House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy, with Liz Cheney standing behind him, has called a press conference to demand that Ocasio-Cortez apologize for her remarks on concentration camps. Her interns continue to receive angry, abusive phone calls, which they report when a message becomes a death threat. Staffers from the office of Nevada Senator Catherine Cortez Masto, who have been accidentally receiving some of them, bring over cookies in support.

AOC and her fellow progressive freshmen women, Rashida Tlaib and Ayanna Pressley, sit together at the front of the assembled committee. These assigned seats, which maybe used to be the nosebleed section, have instead created a perfect frame for C-SPAN screen grabs of the three of them during hearings. (Shots of the group during the Michael Cohen's testimony have been emblazoned on T-shirts.) At a hearing the next day on diversity in the boardroom, AOC will give a little shoulder shimmy of support when Tlaib interrupts Republican Anthony Gonzalez of Ohio.

Ocasio-Cortez leans on Pressley, Tlaib, and Ilhan Omar (D-MN), who also face intense scrutiny as newcomers. It’s easier than seeing a therapist; she has before, but not regularly, plus her current congressional health care plan does not cover her in New York (even legislators could benefit from universal programs, it seems).

Ocasio-Cortez’s voice is clear and high and when she speaks, the room perks up—attendees lift their heads, and people in the audience, especially the younger ones, crane to get a glimpse, whether on the floor or in hearings. A line, mostly of young women, always forms to meet her and take photos. It is less congressional hearing, more celebrity meet-and-greet, a reminder that you are in the same room as someone who declined an invitation to Rihanna’s Diamond Ball last year (it was the night of the New York gubernatorial primary). She agrees to both regular photos and selfies, always with a “Sure” or “Of course.” “OMG I’m in awe, you’re not just on Twitter? On Instagram?” one woman says. “My hands are legitimately shaking right now,” says another. It’s the job of her staffers to gently encourage Ocasio-Cortez to leave when her schedule demands it. As she exits, one little girl simply slumps in her chair in awe, heaving a big sigh.

The walk back to her office in the Cannon Building is a long one, due to construction, and to her lowly freshman status. She doesn’t mind the exercise; she is finally starting to put time for working out back on her calendar. On Twitter, the concentration camp controversy continues apace. She tweeted again during the hearing, I discover. I ask her if there’s a tipping point at which she decides to stop engaging with an issue once Republicans have persistently seized on it. “There is, sometimes,” she says. This isn’t one of them. “Like Elijah Cummings says, ‘The time finds us.’ We have an obligation to speak when the president is threatening to take some kind of mysterious action toward up to millions of immigrants.”

“It makes a very big difference once other people know your heart, and I’ve tried to make an effort to have conversations with lots of members so they understand where I’m coming from.” That might be the key to Ocasio-Cortez’s biggest staying power in Congress: she can express unlikable, uncomfortable ideas (this week, that conditions at the border are cruel and fascist, and have long been so) while somehow remaining likable herself. Even to Mike Johnson, the Louisiana representative who has called the Green New Deal “a guise” to “usher in the principles of socialism,” but who practically gushes about introducing her to his kids on the House floor. It’s what has Ted Cruz reaching out for bipartisan partnership. She describes this capacity as an organizer’s door-knocking aptitude for “meet[ing] people where they’re at.” And she happens to believe that more people can be persuaded to her side than to the other. As we walk through the tunnels of the Capitol Building, we pass a man sitting at a reception desk, who leaps up and hugs her, saying, “Get ’em!”

On my final day in Washington, I meet Ocasio-Cortez and her partner, Riley Roberts, who is walking her to work. They moved into their apartment building in a new development a few months ago for better security, though there was still a scary incident in which a man photographed her when she took a car home late one night. Pictures wound up online in conservative media, around the time that another incident shook the pair, when a different man was allegedly found with an arsenal of weapons and a list of politicians and journalists to kill, including Ocasio-Cortez. She and Roberts have looked into a security detail, but it was far too expensive—plus, they’ve already been called out for living in luxury real estate.

Roberts is a tall, affable software engineer who is now famous online for his red beard after appearing in the Netflix documentary Knock Down the House. He was dragged for looking somewhat bedraggled, what one Twitter user called a “bin raccoon.” His mom sends him raccoon GIFs, and other members tell him occasionally that he “cleans up well”—but he will never get a Twitter account. Roberts largely works from home, so he can pop into the spouses room on the House floor, where there is a snack bar, or hang out with Ocasio-Cortez, (who he calls Alex), when she has late-night votes. “’Cause like, what else am I doing?” he says. He runs interference when they go out in D.C., where they are approached more often than in New York. Did they get some downtime last night? Sort of: They watched Jailbirds, a Netflix documentary series about incarcerated women. And Ocasio-Cortez is reading Leadership in Turbulent Times by Doris Kearns Goodwin.

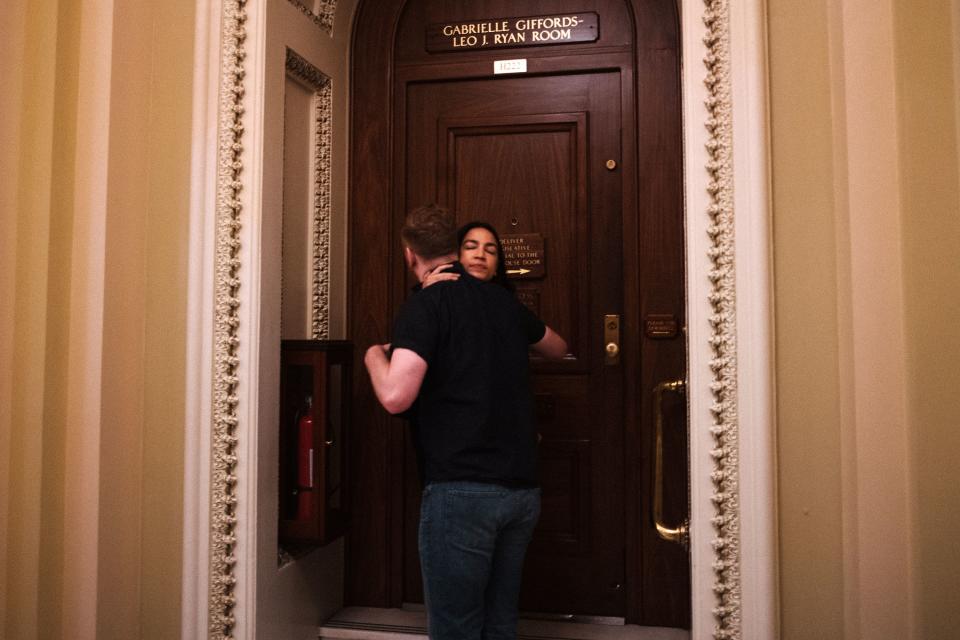

Seeing the two of them enter the House together is surreal. It’s like watching two people you know from college who live together casually walk to work, but work is Congress—which is very nearly what is happening. It’s a thrilling and wholly unknown feeling as a young, unmarried, and childless person to see those people who have lives that look like yours also having lives like theirs. The excitement isn’t in that we might all enter the halls of power one day, but the people there might actually reflect who we are. Older members struggle with relating to their millennial colleagues: “Do you call it a ‘partner’?” Ocasio-Cortez says a Republican once asked her on the floor, who had trouble wrapping his head around their relationship. “Does that mean something?”

Ocasio-Cortez is prepping to deliver her appropriations amendment during a hearing on the floor, where she will advocate for moving $5 million from the DEA to instead fund opioid addiction treatment. She is much less nervous than she used to be. “I do think that when I first got here, almost everyone thought I was a lightweight,” she says, waiting in the empty, very stately Rayburn Room. “Republicans really tried to fuck with me, for lack of a better term.” That included introducing a surprise faux “Green New Deal” amendment, so that she would be recorded voting the measure down. They constantly interrupted her. But they weren’t counting on Ocasio-Cortez shining so much in those five uninterrupted minutes she gets on the floor. “I let them have it, then it probably happened three or four times before they stopped interrupting me ever again,” she says. “Polling shows that affluent women don’t like that. I need to be a gentlelady, and, I mean, I can if I want to be. But I don’t want to be.”

I ask why Ocasio-Cortez still talks explicitly about socialism when some politicians have been jumping on the universal program bandwagon without invoking the GOP’s favorite bogeyman. Ocasio-Cortez is still a member of the Democratic Socialists of America. “I think DSA sometimes has cultural problems in New York—it can really be very much within a specific class-race lens,” she says, which is a “false choice.” But “the reason I think that it’s helpful is because it does give you an overall framework to turn back to. . .a larger framework for thinking about the world.” She thinks of her own victory in NY-14 as an example of this framework’s success. “I think once people start learning about things, they come to the same conclusions that I come to.” She does not like broad, offhand categorizations of people’s politics: when I joke that she is a “kombucha socialist,” she chides me that the security guys in her office gave her scobys, the kombucha starter, as a welcome present.

On the other hand, she also rejects Joe Biden’s “appeal” as a centrist Democratic Party presidential candidate. “I think that he’s not a pragmatic choice,” she says when we discuss his latest comments on working with segregationists. “That’s my frustration with politics today, that they’re willing to give up every single person in America just for that dude in a diner. . .Just so that you can get this very specific slice of Trump voters? If you pick the perfect candidate like Joe Biden to win that guy in the diner, the cost will make you lose because you will depress turnout as well. And that’s exactly what happened to 2016. We picked the logically fitting candidate, but that candidate did not inspire the turnout that we needed.” Despite pressure to endorse, she thinks it’s too early for anyone to do so. “We haven’t even had a debate yet.”

Maybe Ocasio-Cortez is a Type-A socialist. Musing on her own strategy, she says, “You can be radical and you can be respectful—and I know that many people may think that that’s not cool. But I have a genuine desire to connect and to convince. And I actually think that it’s more possible than people give credit for in this institution.”

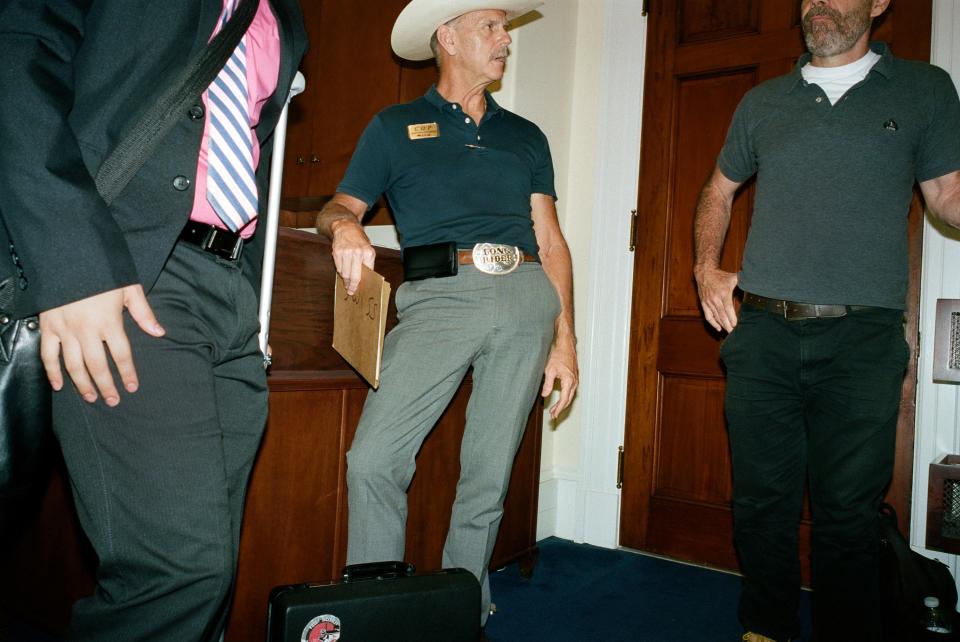

A few hours after her amendment passes, AOC is caught in a scrum of reporters asking her about Iran, with whom it seems Donald Trump might be on the brink of starting a war, and the ongoing concentration camps story. She lists some of the deaths and horrifying instances of assault and mistreatment at detention centers, off the cuff. She seems barely fazed, but fired up. “Good,” when I remind her we're on day three of the controversy around her Instagram live stream. “We should be talking about conditions on our border every damn day. If I have to call it what it is for people to pay attention to it, so be it.” By the following Tuesday, June 25, it will be announced that John Sanders, acting commissioner of the Customs and Border Protection agency, will step down due to mounting public pressure surrounding the treatment of migrant children in detention facilities and their conditions.

Eventually she’s walking home again, for a bimonthly dinner with her team. It has rained, and throngs of suited reps descend the steps of the House into humid, sticky air. Two guys in MAGA hats wave at her.

I want to know, does she despair that what she’s doing to change the world isn’t happening fast enough? Take the new Dream Act, an updated version of which the House just passed—sure to be killed next door. For her, opposition means progressives should be more ambitious in scope, not less. “It’s important to communicate to the world what we want, without apology or exception.”

Free of ties to corporate lobbyists and wealthy donors who keep congressional members from speaking, or tweeting, without prep and PR, Ocasio-Cortez is an enigma to many. She must be a plant, a freak, funded by dark money, selling out, flaming out, giving up. In reality, she is held to account by something huge and overwhelming, burdensome at times: the people-powered movement behind her, which will be there even if she doesn’t get a second term. “When I think about campaigning,” she says of facing a primary challenger in 2020, “I just bust my ass working for the community, and the community will be there.”

A candidate not consumed by reelection feels nearly scandalous. But I get it: Our generation has pretty much only a guaranteed present. “I don’t think too much about [the future]. I’d probably say the most in the future I think about has to do with personal stuff, like how I would handle having children,” she says. She does her best nasally media impression: “Where do you see yourself in five years? I just ask the question, how can I do the most good right now?”

Originally Appeared on Vogue