40 years ago, a groundbreaking record from Englewood changed hip-hop

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

At first, there was no message.

Rap was all bluff and bluster. Party stuff, straight up. Hip hop, you don't stop. Throw your hands in the air, and wave 'em like you just don't care. Somebody scream.

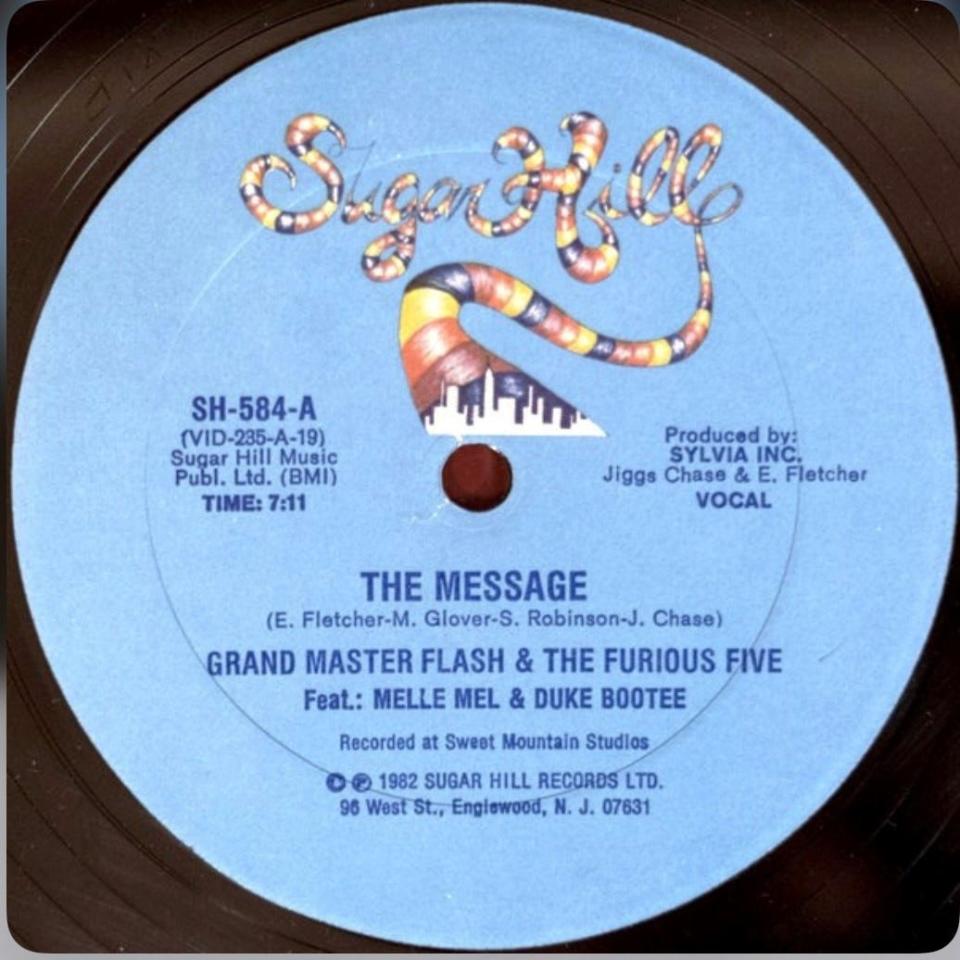

And then — straight outta Englewood — came "The Message." That record, released 40 years ago Friday, hit the reset button.

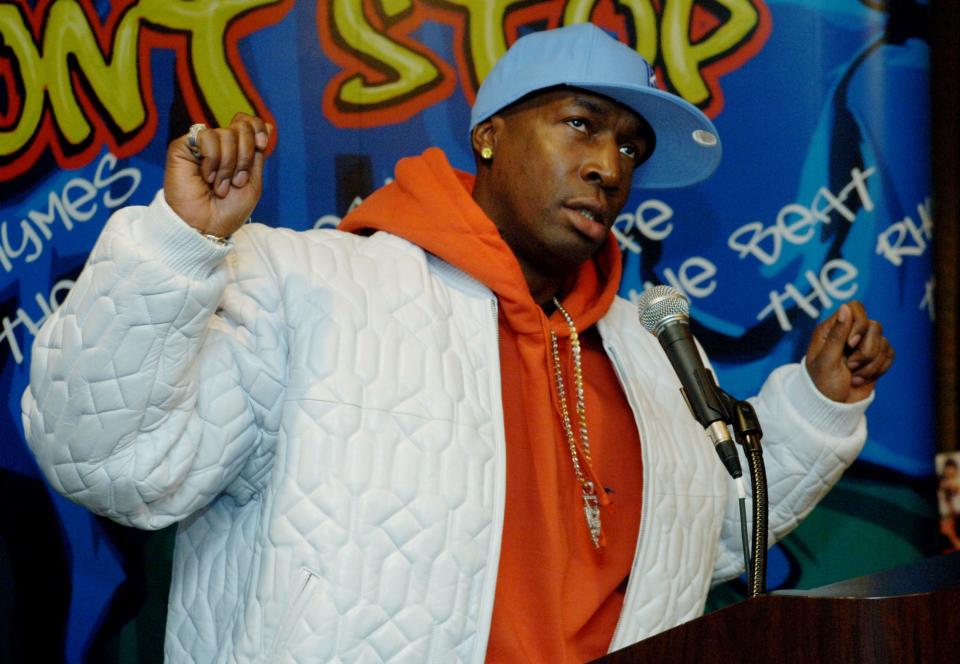

"You could smell the 'hood in the song," said Melvin Glover, aka Melle Mel, the vocalist and one of the key architects of the record.

"The Message," issued July 1, 1982, set the pattern for all the hip-hop records that came after.

It is, arguably, the single most important hip-hop title ever released. A claim that Rolling Stone Magazine bolstered in 2012 by making "The Message" No. 1 in its cover story, "The 50 Greatest Hip-Hop Songs of All Time."

More: Englewood's Sylvia Robinson, founding mother of hip-hop, inducted into Rock Hall of Fame

It was, Rolling Stone said, "the first song to tell, with hip-hop's rhythmic and vocal force, the truth about modern inner-city life in America — you can hear its effect loud and clear on classic records by Jay-Z, Lil Wayne, N.W.A., The Notorious B.I.G., and even Rage Against the Machine."

Earlier, in 2004, Rolling Stone had rated it No. 51 in its "500 Greatest Songs of All Time." In 2007, Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five, the credited artists, became the first hip-hop group inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame.

"The Message" been sampled, or referenced, by everyone from Puff Daddy and Ice Cube to Lin-Manuel Miranda in his "Hamilton" lyrics. And in 2002, it became the first hip-hop recording to be added to the National Recording Registry by the Library of Congress.

Not bad — for a record nobody wanted to make.

No thanks

"We hated it," said Eddie Morris, aka Scorpio of The Furious Five, who remembers the reaction from one and all when the late Sylvia Robinson, co-founder of Englewood's pioneering hip-hop label Sugar Hill Records, brought the lyrics to them.

"We couldn't stand it," he said. "We were all adamant. We were entertainers. This was so different. We just weren't into it."

What Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five had been doing — what virtually all of the proto-hip-hop acts had been doing — is a type of party record in which different MCs would take turns grabbing the microphone and boasting, in rhyme, to the beat.

"If you want to party, say 'party!…"

It was this kind of rap, originating in the block parties of the South Bronx in the mid-1970s, that Robinson — herself inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame this year — was determined to put on wax.

Almost everyone tried to dissuade her from releasing ""Rapper's Delight," with her own ad-hoc rap group The Sugarhill Gang, in September 1979. But that record, by November, had made it to Billboard's Hot 100 — the first bona-fide hip-hop hit. And Robinson was eager to follow up.

Among the acts she signed was Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five — all South Bronx natives, who had been doing their boasting, rhyming thing at street parties since 1978. They had already been signed to another label, Enjoy.

Grandmaster Flash (aka Joseph Saddler) was the turntable guy — in the early days, the scratcher, not the rapper, was the star of the show.

Vocalist Melle Mel, Scorpio, Kidd Creole (Nathaniel Glover, Mel's brother and no relation to Kid Creole and the Coconuts), Keef Cowboy (aka the late Robert Keith Wiggins) and Rahiem (aka Guy Todd Williams) rounded up the "Furious" crew.

Together, they had hits for Sugar Hill in their signature style, starting with 1980's "Freedom." "Melle Mel with the clientele, I'm gonna rock your chime and ring your bell…"

Rap — if it had pursued this course — might have been a soon-exhausted novelty, like disco.

But then Duke Bootee (the late Edward Gernel Fletcher), an in-house producer and percussionist at Sugar Hill, wrote a new kind of hip-hop lyric and passed it on to Robinson.

More: Roller disco is back again. If you're ready to lace up, head to Central Park

More: Danceteria, one of NYC's most influential clubs, lives again online

"He brought it to my mother, and my mother brought it to Grandmaster Flash," recalled Leland Robinson, the only surviving child of the hip-hop entrepreneur.

"She was always a person who could call the hit out any day," Robinson said. "She was always way ahead of her time."

New for '82

"The Message," as it developed, was unlike any rap hit that had been produced up to that time.

The tempo was slower. The vibe was hallucinatory, menacing.

The chorus featured a mad, mirthless, coming-to-take-me-away-ha! ha! laugh — followed by the declaration, "It's like a jungle sometimes, it makes me wonder how I keep from going under." The atmosphere was charged, dangerous: "Don't push me 'cause I'm close to the edge, I'm trying not to lose my head."

And what was driving this guy around the bend? The lyrics are explicit:

"It was reality," Robinson said. "At that time, everybody knew people living in the projects. When an artist writes a true story, that's what works for everybody — because that's what they can relate to."

"The Message" was about all ghettos, everywhere.

But it was also a specific picture of the South Bronx in the late 1970s "Bronx is burning" period — a time when the area was a hellscape of rubble-strewn lots, prison-like projects, crime, drugs, and buildings that would suddenly, suspiciously burst into flame. Scorpio, who lived on 166th Street and Melle Mel, who lived on 165th, knew it well.

"It was like we were living in Beirut," Scorpio said. "For us, it was normal. That was our playground. We used to go into dirty buildings, everywhere we walked we were stepping over dope needles. That's all we had."

Maybe just because it was so close to the bone, "The Message" was a non-starter for almost everybody. Sugarhill Gang rejected it. So did most of the Grandmaster crew.

Rap was their ticket out of the ghetto. The last thing they wanted was to remind themselves, or their listeners, where they'd come from. But Robinson was adamant that this could be a game-changer — and eventually she brought Melle Mel around.

"She was the only one that believed that the record would be as big as it was," Mel said. "I didn't understand the direction she was going with it. I just think it's a testament to Sylvia Robinson. She's easily one of the greatest hip-hop producers, and woman producers, and music producers as well. I don't believe she gets enough credit. The whole thing was basically hers. I just went for the ride."

He did more than that. Mel even brought a verse from an earlier record, "Superrappin'," to round out the record. This one was the grimmest of all:

Touching a nerve

In the end, "The Message" was more of a Duke Bootee-Melle Mel record than a Grandmaster Flash record. It also owed much to guitarist Skip McDonald and co-writer Jiggs Chase. But whatever it was, it was a massive hit — reaching No. 62 on the Billboard Hot 100 (impressive, at that time, for a unproved genre like hip-hop), No. 4 in the Billboard Hot Black Singles, going gold in 11 days, and changing the lives of everyone involved.

"We went on tours," Scorpio said. "We were supposed to do four shows. We stayed out for six months. The first time we went to Hollywood, it felt like we had truly made it. We were kids from the Bronx, all we ever saw was burned-out buildings.

"The first time we stayed at the Hyatt on Sunset, a guy pulls up, rolls down his window and says, 'Hey, I know who you guys are.' It was Muhammad Ali. I'll never forget that in my life. I could have died and went to heaven."

"The Message" was a watershed. It helped popularize the "trance" vibe that became central to much of R&B. It helped put the vocalist, not the DJ, firmly in the center of the hip-hop universe.

Most important, it was a permission slip to rappers everywhere to talk about real things, difficult things, things other than boasting and booty. Authenticity — "street cred" — was suddenly what mattered.

It was this new kind of hip-hop — rap as an underground newspaper, a chronicle of life in the 'hood — that captivated America, took over the charts, and ultimately changed the trajectory of pop music.

"The important thing is what hip-hop did to change society," Mel said. "That's what makes it great."

He himself followed up "The Message" with several more Sugar Hill hits in the same vein: "White Lines (Don't Do It)," "New York, New York."

"When they saw how people reacted to 'The Message,' then people started writing records about reality, about real life," Robinson said.

Four decades and 10,000 hit records later, it might be asked: Did the hip-hop industry get the wrong message from "The Message"?

The lyrics are about crime, drugs and desperation — yes.

But unlike many later hip-hop records, it doesn't celebrate them. "This wasn't just somebody trying to glorify all this," Mel said. "It was a portrait, a rendition."

Compare "The Message" to, say, "Trap Queen" (2015) in which Paterson's Fetty Wap celebrates his drug-cooking girlfriend. "Married to the money, introduced her to my stove, Showed her how to whip it, now she remix it for low…"

A far cry from the guy in "The Message," who just wants to get out of Dodge: "I can't take the smell, can't take the noise…"

"They started glorifying the whores and the pimps and the drugs," Scorpio said. "We didn't even curse on our record."

Jim Beckerman is an entertainment and culture reporter for NorthJersey.com. For unlimited access to his insightful reports about how you spend your leisure time, please subscribe or activate your digital account today.

Email: beckerman@northjersey.com

Twitter: @jimbeckerman1

This article originally appeared on NorthJersey.com: 'The Message': Sugar Hill Song now 40 years old, changed hip-hop