The 44 Percent: Chauvin conviction reaction, DOJ investigation, Oscars

I could very well be nearing my mid-life crisis.

Maybe contemplating one’s own mortality isn’t the best way to start a newsletter. But as a Black man in America, it’s always at the back of my mind. The recent deaths of Black men in their 50s — namely DMX (50), Black Rob (52) and Shock G (57) — have made this thought all the more real.

Although each death was unique, it’s impossible not to see a connection, especially considering Black men have the lowest life expectancy in the country. A 2021 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention study estimated the average life expectancy for Black men to be 68.3. That’s about seven years less than white men (75.5), 12 years than white women (80.6), seven years less than Black women (75.8), eight years less than Hispanic men (76.6) and 15 years than Hispanic women.

These disparities – which existed long before the COVID-19 pandemic and only grew worse because of it – beg the question why. Well the easiest answer is racism: racism in the medical field when it comes to treatment; racism in urban planning such that Black neighborhoods have a greater likelihood of being food deserts; and even racism in general.

“Racism literally makes people old,” David H. Chae, an epidemiologist, told The Atlantic. Chae led a team of researchers that discovered middle-aged Black men who experienced race-based discrimination have shorter telomeres, the DNA sequences that cap chromosomes which biologists believe to be linked to aging.

I know you’re probably thinking, “Slow your roll, Zay. You’re only 24. You have a long life ahead of you.” And hopefully you’re right. I’d love to one day have kids, see my kids have kids and maybe even my grandkids have kids. But the odds are against me. And that’s haunting.

Now let’s start the show:

INSIDE THE 305

Chauvin conviction won’t itself change policing. For many Black Miamians, the fight just began:

“What is real change going to look like?”

This question, posed by Harold Ford, the NAACP Florida State Conference area director for Miami-Dade and Monroe counties, gets at the heart of my recently published story about Black Floridians’ reaction to Derek Chauvin’s conviction of murdering George Floyd. The people I spoke expressed feelings of joy but also commitment that one conviction doesn’t solve longstanding issues of racism in law enforcement. As community organizer Valencia Gunder put it, now is the time for America to have a real conversation about public safety.

“It is time for America to reevaluate its principles and its foundation as it relates to how it treats Black people, people of color and under-resourced populations,” she said.

One of the anecdotes that will forever stick with me is how many of the subjects, without prompting, refused to call Chauvin’s conviction justice. They instead called it accountability, or a singular moment of doing the right thing. Justice, as attorney Marlon Hill explained, would involve more widespread changes.

“Justice takes more than one case to happen,” Hill explained. “It takes the transformation of a culture, of a society.”

Related Coverage:

A red wave followed Floyd protests in Miami. But activists want to revive the movement

‘Does it change anything?’ South Florida leaders react to Chauvin guilty verdicts

We shouted ‘Hallelujah!’ after verdict, but true justice is an arduous journey | Opinion

Miami-Dade’s wealthiest areas are almost fully vaccinated. Black communities are at 31%:

Vaccine access has been an issue in many primarily Black communities across the country, but this Herald analysis really put it into perspective. The findings, specifically that many of the ZIP Codes with the lowest vaccination rates are primarily Black communities, illustrate that “vaccine hesitancy” is no longer the biggest hurdle to inoculation. Georges Benjamin, executive director of the American Public Health Association, put it more bluntly:

“Equity doesn’t happen automatically. It happens by intent,” Benjamin told the Herald. “So if you’re trying to achieve equity, you have to devise a plan that will achieve equity. And if you don’t do that, you will get what you got: an unequal distribution. That’s not rocket science. That’s math.”

Look at the actual numbers and the disparity becomes even more glaring. The ten ZIP codes with the lowest vaccination rates, which includes areas like North Miami, Liberty City and Miami Gardens, have inoculated about 30% of adults compared to 88% in the top 10. Experts contend that this is because Gov. Ron DeSantis’ roll-out plan prioritized age and ignored research that proved color-blind health practices often don’t engender equity.

OUTSIDE THE 305

Upcoming voting rights legislation divides Black Democrats:

Summer 2021 might be “make or break” for Democratic lawmakers.

As The New York Times’ Astead Herndon notes, the Democratic members of Congress have one giant question mark going forward: Can they rally enough support for legislation that will make voting more accessible? Many Black Southern lawmakers are themselves in a quandary considering that some pieces of legislation would combat gerrymandering practices that have “diluted Democrats’ influence regionally, but it also ensures that each Southern state has at least one predominantly Black district, offering a guarantee of Black representation amid a sea of mostly white and conservative House districts.”

Ultimately, Congress will have their choice of two bills. There’s the John Lewis Voting Rights Act, or HR 4, which would restore key provisions of the original 1965 Voting Rights Act, including requirements that some state’s get approval before changing election laws. Then there’s HR 1, the For the People Act, which makes more specific changes like restoring voting rights to the previously incarcerated, allowing for Election Day registration and other changes. Eric H. Holder Jr., the attorney general under President Barack Obama who now runs a voting rights advocacy organization, had this to say to about the status of the two bills:

“The stakes are the condition of our democracy,” Mr. Holder told the Times. “This is more than a partisan ‘who wins and who loses?’ game. If we are not successful in HR 1 or HR 4, I am really worried our democracy will be fundamentally and irreparably harmed.”

DOJ to investigate policing in Louisville, Ky.:

Finally a step towards justice.

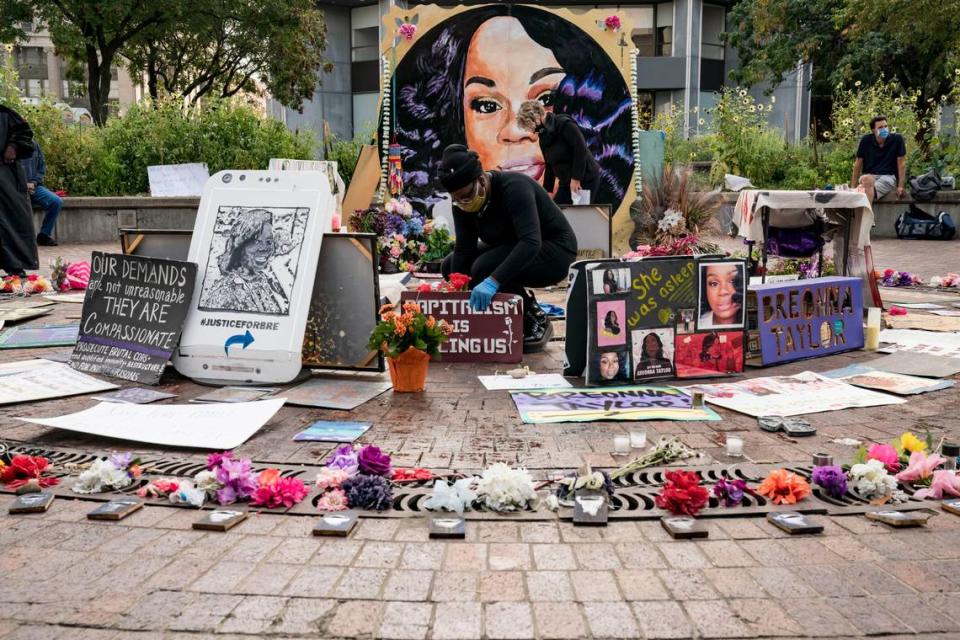

The Justice Department will investigate policing in Louisville, Ky. concerning the death of Breonna Taylor, a 26-year-old emergency medical technician whom officers killed in her own home. Taylor’s death, along with that of George Floyd, sparked a national outcry over police after it was determined that officers used a knock-warrant to enter into her home as part of a narcotics investigation that yielded no drugs.

“I think it’s a good thing,” Louisville Chief Erika Shields told the Associated Press. “I think that it’s necessary because police reform quite honestly is needed in near every agency across the country.”

This announcement comes less than a week after the DOJ opened a probe into Minneapolis police following the murder of Floyd.

According to the AP, the Louisville investigation, officially known as “pattern or practice,” will focus on many things including whether the Louisville Metro Police Department “engages in a pattern of unreasonable force,” “the system in place to hold officers accountable” as well as “’assess whether LMPD engages in discriminatory conduct on the basis of race.’”

Only one officer, Brett Hankison, faced charges following Taylor’s death. A grand jury indicted Hankison on the charge of wanton endangerment after he fired 10 shots into Taylor’s apartment, three of which ripped through her walls and flew into her neighbor’s home. No one was actually charged for killing Taylor

HIGH CULTURE

The Oscars’ delivered mixed results:

It’s not possible for the Oscars’ to make history for diversity yet fold when it matters most? Well you just don’t know the Academy.

In a year where both women and people of color were more represented than ever, the Oscars’ still managed to bungle at least one category – that being best actor which went to Anthony Hopkins for his role in “The Father” rather than the late Chadwick Boseman, whose portrayal of a talented yet troubled trumpeter in “Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom.”

That’s not to say the Oscars’ fumbled the bag completely. Chloé Zhao became the first woman of color to win Best Director for “Nomadland.” “Minari” standout Yuh-jung Youn became the first Korean winner of an acting Oscar. Mia Neal and Jamika Wilson became the first African Americans to take home the best makeup and hairstyling award for “Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom.”

Happy Fifth Birthday, “Lemonade”:

The Beyhive might kill me if I didn’t mention that Beyoncé’s critically acclaimed album “Lemonade” turned five on April 23. Half a decade later, it’s safe to say Yoncé really changed the game with this one. Make sure you give “Lemonade” a run this week to see if it still hits the same after five years (spoiler alert: it will).

Where does the name “The 44 Percent” come from? Click here to find out how Miami history influenced the newsletter’s title.

Also, I noticed in the last newsletter that I misspelled Ahmaud Arbery’s last name. Charge that mistake to my head not my heart.