After 48 years of imprisonment, Glynn Simmons formally exonerated in Oklahoma

An Oklahoma man who served the longest wrongful imprisonment in U.S. history has now been formally declared innocent of a murder he has always maintained he did not commit.

Oklahoma County District Court Judge Amy Palumbo ruled in favor of Glynn Simmons, updating the dismissal of his murder conviction with a declaration of "actual innocence" Tuesday.

In granting Simmons' request, Palumbo said she had reviewed decades' worth of transcripts, reports, testimony and other evidence while preparing to make her decision.

"This Court finds by clear and convincing evidence that the offense for which Mr. Simmons was convicted, sentenced and imprisoned in the case at hand, including any lesser included offenses, was not committed by Mr. Simmons," Palumbo said.

More: Judge formally dismisses murder case after man spent 48 years in Oklahoma prison

Prosecutors, attorneys dispute 'failure of proof' in Simmons case

Simmons had been convicted of the December 1974 murder of Carolyn Sue Rogers, who died after being shot during an Edmond liquor store robbery. After 48 years of incarceration, he was released from prison earlier this year when Oklahoma County District Attorney Vicki Behenna determined that prosecutors had violated Simmons' right to a fair trial by not disclosing a police lineup report to his trial lawyer.

While Behenna had decided not to pursue a retrial and agreed to dismiss Simmons' murder conviction, she had been reluctant to describe Simmons' case as "exonerated." Her office had objected to Simmons' actual innocence claim, saying that the state could not prove Simmons' guilt "beyond a reasonable doubt" and that an eyewitness would not recant her identification of Simmons in 1975.

“The state had a failure of proof — that’s the only reason for the requested dismissal,” Behenna wrote in court filings dated Oct. 18. “This simply is not an ‘actual innocence’ case where DNA was used to exonerate a person; or a conviction was obtained using ‘forensic’ evidence that was later debunked; or where an eyewitness recanted their identification; or where the actual perpetrator of the crime confessed to the commission of the crime and the details of that confession were later corroborated by independent evidence.”

Simmons' attorneys, Joe Norwood and John Coyle, said that the lineup report was "powerful innocence evidence" because it showed the eyewitness, who had survived being shot in the head during the robbery, did not actually identify Simmons.

"Not only would the withheld lineup report have changed the outcome of Simmons trial, but it would also have prevented the State from being able to try Simmons at all," the lawyers wrote Nov. 17. They also pointed to the testimony of a dozen witnesses who said that Simmons had been in Louisiana at the time of the murder.

His attorneys also said that the "actual innocence" claim was a necessary first step in Simmons being able to pursue monetary compensation from the state for the several decades he spent wrongfully imprisoned. But any compensation, Norwood cautioned, was not guaranteed and could be long into the future.

“He had 50 years stolen from him, the prime of his work life when he could have been getting experiences, developing skills. That was taken from him, by no fault of his own, by other people,” Norwood said. “Whatever compensation he has coming is down the road, but I would just encourage people to donate to Glynn's GoFundMe, because money ain’t showing up in his bank account tomorrow.”

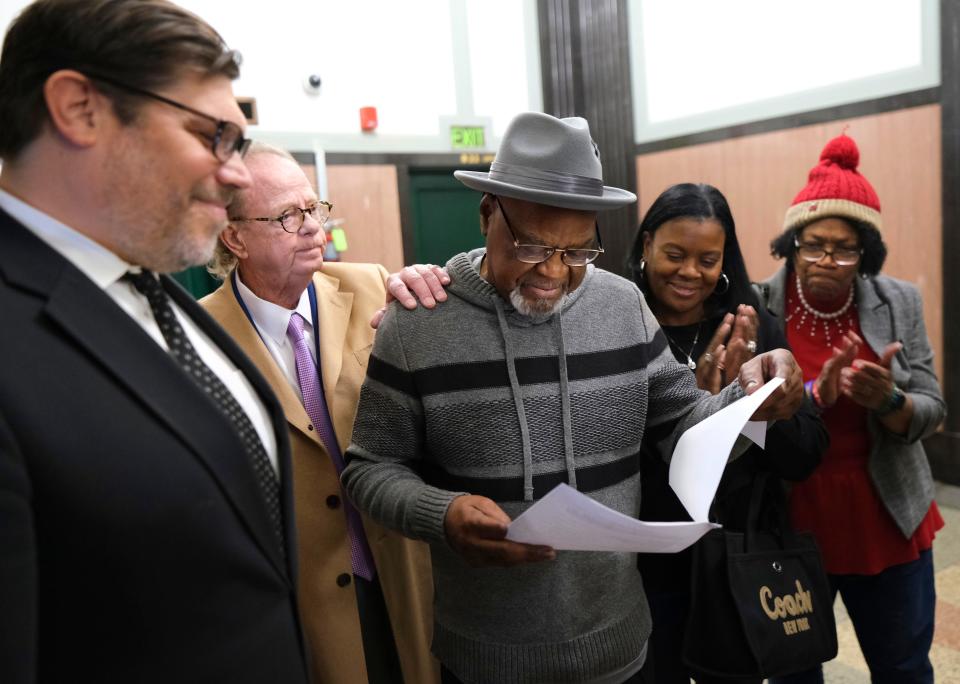

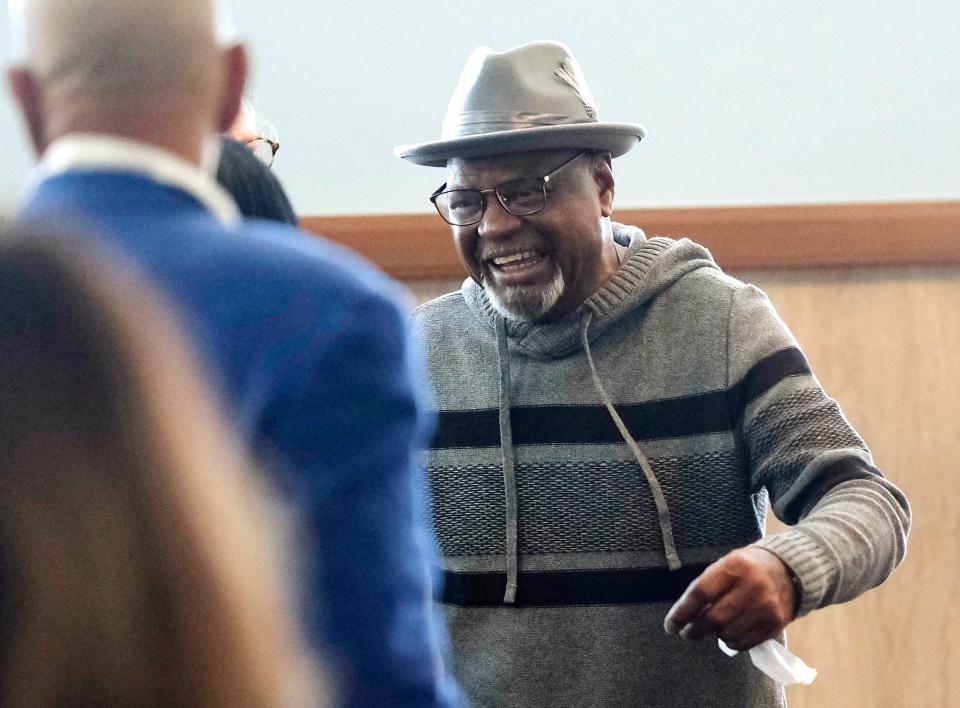

Simmons said Palumbo's ruling Tuesday was a confirmation of something he had known all along for nearly 50 years: that he was an innocent man.

"This is the day we've been waiting on for a long, long time. It finally came," Simmons said. "We can say justice was done today, finally, and I'm happy."

Kim T. Cole, a civil rights attorney based in Texas, supported Simmons on Tuesday and said the state needed to be held accountable for “robbing” Simmons of five decades of his life.

“It’s too late for justice, at this point, but it’s not too late for retribution,” Cole said. “Retribution is due.”

'Black people's voices need to be heard'

Don Roberts, Simmons' codefendant in 1975, also was convicted of Rogers’ murder. At the time, both men received the death penalty, but their sentences were modified to life in prison after a 1977 U.S. Supreme Court decision. Roberts was released on parole in 2008.

The University of Michigan Law School’s National Registry of Exonerations lists Simmons as the longest-served wrongful incarceration in its database of exonerees.

Simmons’ exoneration comes amid a time of heightened scrutiny of both mass incarceration and the death penalty throughout the United States. Counties with high numbers of wrongful convictions show patterns of systemic misconduct from police and other officials, and researchers argue that race often plays a role.

More: Oklahoma tied for the 2nd most death row convictions overturned in the US. Who are the 11 people?

Perry Lott — another high-profile exoneree who saw his 1988 Pontotoc County rape conviction officially overturned this year thanks to DNA testing — appeared at the court Tuesday in support of Simmons.

He was visibly moved as Palumbo revealed she would grant Simmons’ request, and he later told The Oklahoman he’d noticed the parallels in the cases between him and Simmons.

“People need to understand that Black people’s voices need to be heard, once and for all,” Lott said. “We’re not angry, we’re not upset, but there’s an enemy out here and he’s not seen.”

“Don’t be scared to stand up for what’s right,” Lott added. “We need your voice in this war against injustice.”

This article originally appeared on Oklahoman: Glynn Simmons formally exonerated in judge's ruling