‘A $5 billion Band-Aid’: Community groups push back on Army Corps plan for Miami-Dade

In the past decade or so, the Miami-Dade area has come up with plenty of ideas to address sea level rise and storm surge flooding. None of them involved a wall down the coast of the county until the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers unveiled its draft plan to protect the region.

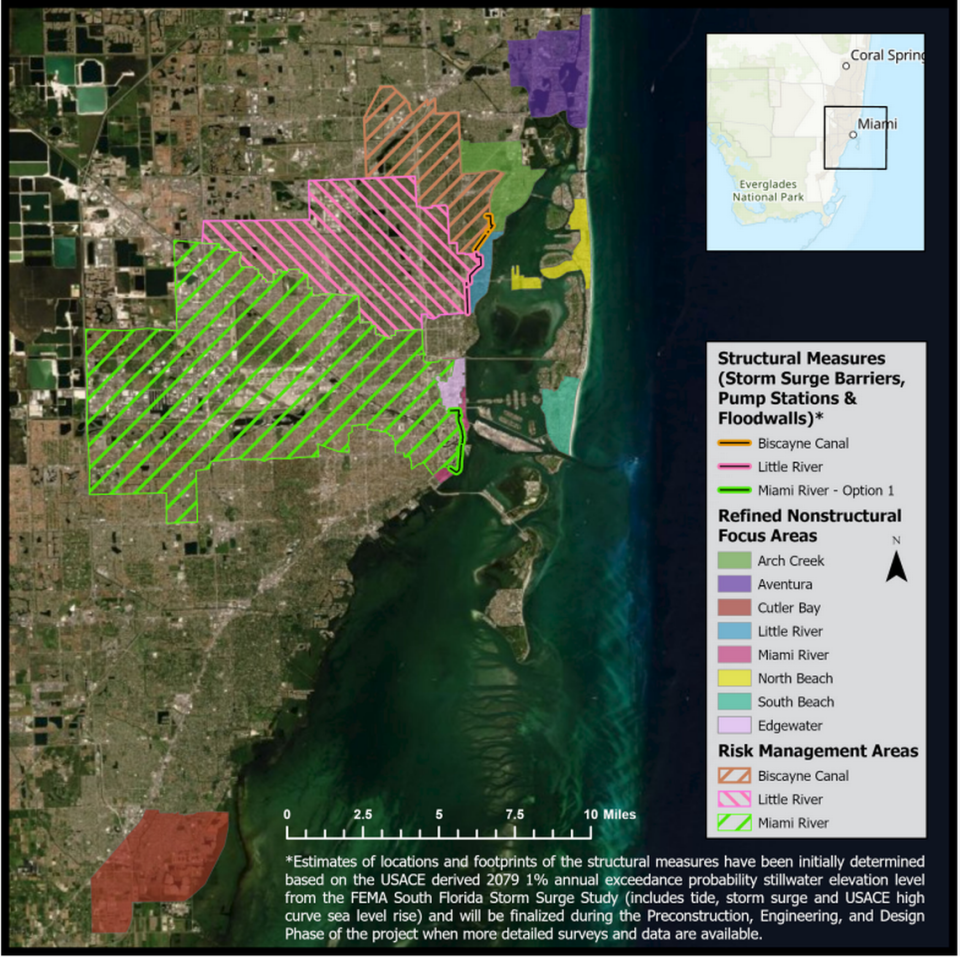

The $4.6 billion plan calls for six miles of walls along the coast (including one mile within Biscayne Bay), barriers at the mouths of three waterways, planting mangroves in Cutler Bay and elevating thousands of properties across the county.

The potential for billions of dollars of investment in Miami-Dade, one of the most vulnerable spots in the country to the effects of rising seas, is welcome. But residents and community groups are pushing back on parts of the plan they see doing more harm than help.

Advocates worry that the Corps’ property-value-based calculations mean those protections will largely benefit richer, whiter communities. Environmentalists question the damage a mile of wall in Biscayne Bay itself could do to seagrass and other wildlife. Climate activists point out the plan’s narrow focus doesn’t address what’s arguably a more pressing problem in Miami-Dade — flooding caused by sea-level rise.

“There’s a lot of missed opportunities for how we would spend billions of dollars to make this community more resilient. The options considered in this plan are way too limited and don’t consider the needs of the community,” said Rachel Silverstein, executive director of Miami Waterkeeper.

Yoca Arditi-Rocha, executive director of the CLEO Institute, called it “a $5 billion Band-Aid.”

Feds have $4.6 billion plan to protect Miami-Dade from hurricanes: walls and elevation

Ahead of a planned Corps presentation to Miami’s City Commission on Thursday, community groups have asked residents to offer feedback on the plan and encourage the Corps to address their concerns.

The Corps extended its public comment period from July 20 to Aug. 19 after a request from Miami-Dade County, which is still working on its official response to the draft plan announced June 5.

There are no plans for the county, the local sponsor of the project, to have its commission review the draft plan. “We’ve had no request for a presentation,” said James Murley, Miami-Dade’s chief resilience officer.

‘Winners and Losers’

The most dramatic aspect of the plan, the walls, has drawn the most ire. The Corps is many years from finalizing where they’d be built, and what properties they’d need to acquire to build them, but initial plans call for constructing miles of walls ranging from 6 to 13 feet high in Brickell and along the floor of Biscayne Bay, as well as a shorter stretch from Little River through Miami Shores largely following Biscayne Boulevard.

The flood walls are meant to anchor surge barriers at the mouths of the Miami River, Little River and Biscayne Canal that close ahead of major storms and stop the rush of storm surge up the rivers. Because of the need for high ground, most of the proposed locations are slightly inland, leaving whole blocks outside.

“It creates winners and losers and divides neighborhoods,” said Silverstein. “It has echoes of past projects like building highways right through Overtown, and it’s going to have really problematic consequences.”

A September version of the plan showed Brickell’s flood wall a block inland, but after pushback from the city and residents, the June version shows the flood wall on the edge of the coast, with about a mile’s worth slightly offshore in Biscayne Bay.

The Brickell Homeowners Association warned its members, in an email urging them to contact Miami commissioners, that “the project, as proposed, may end up having an overwhelmingly detrimental effect on the entire waterfront area.”

Silverstein called the idea of building a wall in the bay “utterly unacceptable,” and said she doesn’t see the community supporting it.

Spencer Crowley, a member of the Downtown Development Authority, said in a meeting discussing the plan that the organization should encourage the Corps to select a different solution that doesn’t potentially harm the bay.

“It’s a huge part of what makes Miami Miami. It’s a huge part of our real estate economy. It’s a huge part of our local government tax revenues. To do something that would really damage that is something we need to fight against,” he said.

Equity problems

The latest version of the plan also removed a potential flood wall in Edgewater that could have required buyouts of several expensive condominiums in lieu of more homes elevated and buildings flood-proofed, which some advocates see as a more palatable and less disruptive protective fix.

Leonard Shabman, a senior fellow at Resources for the Future, said the Corps has always based its analyses on property value, which means the benefits are usually oriented toward higher-value properties.

“The definition of benefits is tied to land values. So the presumption is that as the risk goes down, land values go up and the people who benefit would be willing and able to pay for that,” he said.

Decades of efforts to have the Corps consider other effects like “social well-being” haven’t expanded the way benefits are calculated, although the Corps does look at the social and economic conditions in the area subject to flooding as it chooses the focus areas for a study.

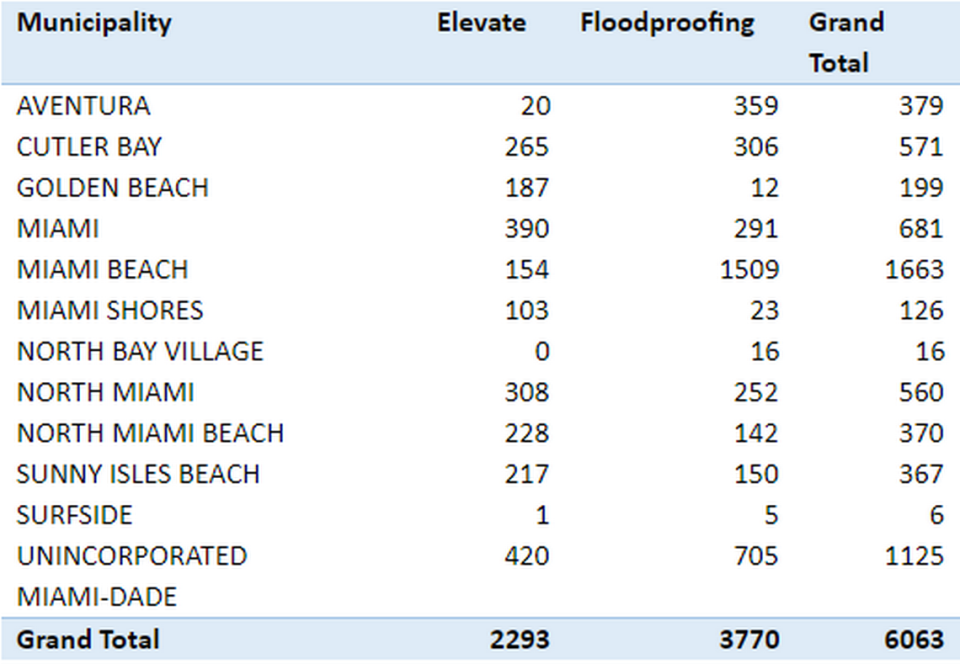

The breakdown of which communities could see more elevations and flood-proofing also leaves advocates with concerns about the Corps’ calculations.

Golden Beach, one of the wealthier ZIP codes in the county, could see 184 of its 364 single-family homes elevated, while just down the beach, Surfside is only slated for one elevation.

Katherine Hagemann, the county’s resilience program manager, cautioned this was just an initial estimate, not the final version of the plan.

“It is important to remember that this is a large area. Their first pass is based on geographic information system analysis and property appraiser data, and the methods they use are passed down by Army Corps policy, which obviously skews toward protecting areas of higher prop value,” she said. “They have said they’re open to refining the plan moving forward so there is neighborhood cohesiveness.”

Natural solutions

The county resilience office highlighted one of the more popular provisions of the plan — money to strengthen and flood-proof critical buildings across the county like fire stations, hospitals and water treatment stations.

However, the Corps’ current plan doesn’t include what is perhaps the most vulnerable piece of infrastructure in the county, the sewage treatment plant on Virginia Key.

Environmentalists also wanted to see the Corps suggest natural solutions like living shorelines in more places than Cutler Bay. In a county-led brainstorming workshop held with residents ahead of the study, natural solutions were consistently the most popular.

Silverstein said the Corps has long promoted coral reef restoration as a cost-effective and natural way to protect an area from storm surge, but questioned why the Miami-Dade plan doesn’t call for it.

“If you’re not going to do reef restoration for a storm surge prevention plan in Florida, then where are you going to do it?” she said.

The Corps’ congressional-mandated focus on storm surge, rather than so called sunny-day flooding or any other climate change-related issues, frustrated climate action advocates like Arditi-Rocha. While some solutions, like home elevations or flood-proofing critical infrastructure, do double duty, the key feature of the plan — the walls — solely addresses storm surge.

“Are we really going to be storm ready by 2080 by putting up walls and elevating properties and installing more flood pumps? Probably not. It’s just going to take one Hurricane Dorian to stall over Miami to tell us that this climate crisis is a lot more complex than trying to mitigate storm surge,” Arditi-Rocha said.

To submit a comment on the draft plan, email MDBB-CSRMStudy@usace.army.mil or visit http://arcg.is/fm0Xe. They can also be sent by mail to: Ms. Justine Woodward, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Norfolk District, 803 Front St., Norfolk, VA 23510. The deadline for all comments is Aug. 19, 2020.