5 Hidden Parkitecture Gems You Need to See for Yourself

Part of the appeal of visiting state and national parks is the immediate—and sometimes drastic—change of scenery they provide as you make your way onto park property and past the welcome sign. In some cases, there’s a particular rock formation, striking waterfall, or rare landscape found within the park that draws tourists from around the world. For other parks, the appeal is simply the chance to be surrounded by nature and reap its benefits while strolling on well-maintained trails.

But unless you’re in need of a restroom, you probably don’t deliberately seek out the manmade structures found in parks. In fact, you may not have even noticed them in the first place, as they seem to blend in with their surroundings—architecturally camouflaged. As it turns out, that is usually by design—specifically, a style called National Park Service (NPS) Rustic, but affectionately referred to as “parkitecture.” Here’s a brief look at the history of this aesthetic, how it made its way into state and national parks across the country, and a few examples of parkitecture you can visit on your summer road trip.

What is parkitecture?

When the country’s first national parks were established in the late 19th century, many of their early public-facing buildings—like lodges and information centers—were constructed in a similar rustic, Arts and Crafts style, using materials like wood and stone that are native to the area. The idea was for the structures to appear as if they were part of the natural environment instead of standing out and drawing attention away from the landscape—taking on the form of log cabins in heavily forested areas, or Pueblo-style architecture in parts of the southwest.

The first official architectural guidelines for parks were established in 1918, two years after the creation of the NPS itself, and stipulated that “in the construction of roads, trails, buildings, and other improvements, particular attention must be devoted always to the harmonizing of these improvements with the landscape.” This “back-to-nature” aesthetic became known as NPS Rustic, or, colloquially, as “parkitecture.”

To the future and back

Around the same time, outside of the parks, Arts and Crafts–style architecture was falling out of fashion: The intricate craftsmanship it required wasn’t financially feasible following World War I, and the sleek lines of modernism complemented the social and public health progress and reform of the time. While some Art Deco and Art Moderne buildings were constructed within national parks—including several examples in the Mammoth Hot Springs section of Yellowstone—the more traditional rustic style never went away.

This is especially evident in the work of architect Herbert Maier who, throughout the 1920s, designed some of the first museums and interpretive centers in parks across the country, including Yosemite, Yellowstone, the Grand Canyon, and Bear Mountain State Park in New York. The most influential of these was the Norris Museum, which opened in Yellowstone in 1930—and continues to function as the visitors’ gateway to the Norris Geyser Basin today—and helped define what became the six principles of parkitecture.

But the most widespread proliferation of parkitecture occurred between 1933 and 1942 with President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s creation of the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) as part of the New Deal. This Depression-era program put young people to work constructing everything from trails to lodges in both state and national parks across the country, with most buildings and signage being in the classic NPS Rustic style. This was no coincidence: Maier was the CCC’s regional officer for the southwest, giving him the chance to implement parkitecture design on a massive scale.

In 1956 the NPS launched Mission 66, which aimed, in part, to modernize national parks and make them more automobile-friendly in time for their 50th anniversary in 1966. More than 100 new visitors centers were constructed during that period, most of which embraced the simplicity of modernism—not only for its popularity in midcentury America, but also because the style was far less time consuming than the handcrafted look of parkitecture. While construction on Grant Village in Yellowstone began under Mission 66, it continued over the course of three decades and utilized a range of styles, including postmodernism (most notably the dining room). But the era of modernism in the national parks came to an end in the early 1980s, when the NPS decided to return to its architectural roots and embrace parkitecture once again. Since then, most new buildings and renovations to older structures feature a Neo-Rustic Revival style.

Visit these classic parkitecture buildings

There are still many early NPS Rustic buildings in state and national parks throughout the country that you can visit today. If your summer road trip involves a trip to a park, here are five examples of parkitecture you shouldn’t miss:

The Old Faithful Inn in Yellowstone National Park, Wyoming

Considered one of the first large-scale examples of parkitecture, the Old Faithful Inn opened its doors in 1904 and will begin welcoming guests once again the first weekend of June 2021. With views of its namesake geyser and a grand lobby that is still one of the largest log structures in the world, the inn remains one of the most popular lodging options in Yellowstone. A must-see for fans of parkitecture, the Old Faithful Inn still contains many of its original decorative features, including etched glass panels, a large stone fireplace, timber columns, log stairs with pine railings, hickory furniture, and an antique, handcrafted clock made of copper, wood, and wrought iron.

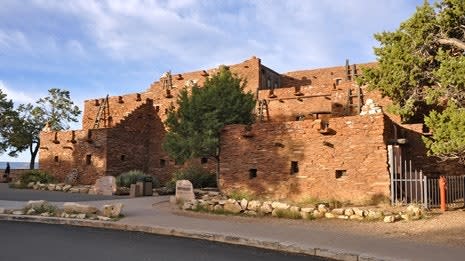

El Tovar Hotel and Hopi House, Grand Canyon National Park, Arizona

Chicago architect Charles Whittlesey envisioned El Tovar Hotel as a cross between a Swiss chalet and a Norwegian villa, constructed using native stone and logs from local trees so it would seamlessly blend into its surroundings at the Grand Canyon. El Tovar opened in 1905—as did the Mary Colter–designed Hopi House, originally used as a souvenir shop and modeled after 10,000-year-old Hopi dwellings. Its rectangular shape and reddish-brown sandstone walls offer a different version of parkitecture than the one directly across the street at El Tovar Hotel, incorporating both indigenous materials and cultural inspiration. It’s possible to visit both buildings on a trip to the Grand Canyon, though it’s tough to snag an overnight stay at El Tovar, which books up months in advance.

Bear Mountain Inn, Bear Mountain State Park, New York

When the Bear Mountain Inn opened in 1915, The American Architect gave it credit for being one of the “finest examples of rustic Adirondack architecture in America.” Constructed using local chestnut timber and stone from colonial-era boundary lines found in different parts of the park’s property, Bear Mountain Inn is an early example of parkitecture. While some of the decorative motifs and historic details were lost or concealed during changes made to the building between the 1930s and 1980s, many were restored during a nearly-six-year renovation that began in 2005. The inn is currently open, and remains a popular weekend getaway from New York City.

Sylvan Lake Lodge, Custer State Park, South Dakota

Sylvan Lake Lodge was built in 1937, nestled in a hillside forest of pine and spruce trees—a location that Frank Lloyd Wright had recommended. Constructed using local timber and stone, the lodge overlooks Sylvan Lake and the rock formations that surround it, allowing visitors to experience the natural landscape of the Black Hills regardless of whether they were hiking outdoors or having a meal indoors. A new wing with additional rooms opened in 1991, and the property also includes 31 cabins scattered throughout the hillside. This year, Sylvan Lake Lodge will welcome visitors at the end of April and is currently accepting bookings.

Originally Appeared on Architectural Digest