11 inspiring Black American heroes whose stories deserve to be celebrated

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Black History Month was created to commemorate the lives and achievements of Black Americans, and Black history lessons frequently include the stories of famous Black Americans like Martin Luther King Jr., Rosa Parks and Jesse Owens.

However, many notable Black leaders and luminaries were inadequately recognized for their achievements due to discrimination and prejudice.

There are a number of hidden heroes that are rarely discussed in classrooms, or around the dinner table, and while their names might not sound immediately familiar, these famous figures have shaped history and deserve the spotlight.

“Black history is often taught from a one-sided perspective, what happened to Black folks,” author and antiracist educator Britt Hawthorne tells TODAY.com.

“Instead, we need to teach Black history from what Black folks did to resist, experience joy, and continue to create in spite of white supremacy.”

Gerald Horne, Moores Professor of History and African American Studies at University of Houston, spoke to TODAY.com about the lack of Black history in schools and history books.

"The reason is simple," Gerald Horne, Moores Professor of History and African American Studies at University of Houston tells TODAY.com. "Just look at the legislative backlash to Critical Race Theory or the Virginia gubernatorial race. Black history well taught leaves discomfort, which many would prefer to avoid."

Horne says that a fuller understanding of Black history isn't just about looking back into the past, it's also about improving the future for America.

“[The] history of a nation helps said nation better comprehend what ails it, so as to prescribe effective remedies," he says.

11 Inspiring Black American Heroes

Here are Black American heroes to celebrate this month — and every month.

1. Claudette Colvin

While Rosa Parks' name may be synonymous with the Montgomery Bus Boycott, Claudette Colvin came first.

On March 2, 1955, 15-year-old Colvin was on her way home from high school in Montgomery, Alabama when she refused to give up her seat to a white woman and move to the back of the bus.

Colvin was inspired by black leaders she had learned about in school.

"Can you imagine all of that in my mind? My head was just too full of black history, you know, the oppression that we went through. It felt like Sojourner Truth was on one side pushing me down, and Harriet Tubman was on the other side of me pushing me down. I couldn’t get up," Colvin told NPR in 2009.

She was handcuffed and arrested for her refusal.

“All I remember is that I was not going to walk off the bus voluntarily,” Colvin said.

The incident occurred nine months prior to Parks’ famed refusal.

In June 1956, Colvin was one of five plaintiffs in "Browder v. Gayle," the first federal court case filed by a civil rights attorney that challenged bus segregation.

A three-judge U.S. District Court panel determined Alabama's bus segregation laws to be unconstitutional. The state of Alabama appealed the ruling, taking the case to the U.S. Supreme Court.

On November 13, 1956, the Supreme Court upheld the lower court's ruling and affirmed bus segregation laws were unconstitutional.

2. Alice Coachman

Alongside Jesse Owens, Alice Coachman is an important name to remember in the field of athletics.

Coachman was the first Black woman to win an Olympic gold medal.

"My father wanted me to be more like a young lady and sit on the porch," Coachman told the New York Times, reflecting on her childhood. "But I would go out back and jump over the fence and straight down the street where they were playing ball."

Coachman's medal was achieved at the 1948 Olympic Games in London where she leapt 5 feet 6 ⅛ inches to earn the top spot in the high jump, beating out Britain’s Dorothy Tyler.

After her win, Coachman returned to the United States where she was celebrated with motorcade parades, yet faced strict segregation in the South. She retired from track and field and became a teacher.

In 1952, Coachman achieved another historic first: becoming the first Black woman to endorse an international product when Coca-Cola hired her to become a spokesperson for the brand.

She was inducted into the National Track and Field Hall of Fame in 1975.

Coachman died in Albany, Georgia on July 14, 2014, at the age of 90.

3. Harlem HellfightersThe 369th Infantry Regiment, nicknamed the "Harlem Hellfighters," was an all-Black U.S. regiment formed during World War I.

The Harlem Hellfighters became the first African-American infantry unit in the first World War, and spent more time in combat than any other American unit.

Initially deployed to help unload supply ships, the regiment faced discrimination from white American soldiers, many of whom refused to serve with black soldiers.

The regiment was then loaned to the French Army, which was in need of reinforcements and welcomed the Hellfighters, and spent 191 days on the front lines.

Though the unit lost 1,500 men, and only received 900 replacements, the Hellfighters were the first unit of the French, British or American Armies to reach the Rhine River at the end of the war.

Hellfighters Henry Johnson and Needham Roberts became the first American soldiers to receive the Croix de Guerre, a French military award for valor in the field.

The Hellfighters are said to have received their formidable nickname from the Germans; "Hollenkampfer" in German translates to "Hellfighters." Because most of the unit hailed from Harlem, New York, the name stuck.

The Hellfighters were lauded in Europe for their bravery, and the entire unit was honored with the Croix de Guerre by the French government.

When the war ended and the Hellfighters returned home, they and other black soldiers still faced racism and segregation from the country they bravely defended.

The summer of 1919 was called the "Red Summer," and marked by violence against Black Americans at the hands of white Americans.

4. Ronald McNair

Ronald McNair was 9 years old when a South Carolina librarian told him he could not check out books from a segregated library in 1959. Refusing to leave, a determined McNair sat on the counter while the librarian called the police, as well as McNair's mother. The police arrived, told the librarian to let the young boy have his books, and McNair walked out alongside his mother and brother.

McNair went on to earn his Ph.D. in physics at MIT and became one of the first Black Americans selected as astronauts by NASA, alongside Guion S. Bluford, Jr. and Frederick Gregory.

McNair's first spaceflight was the STS-41-B mission, aboard the "Challenger" shuttle. He successfully maneuvered the robotic arm, which allowed astronaut Bruce McCandless to perform the first space walk without being tethered to the spacecraft.

He was the second African American astronaut to travel into space.

The second space flight for McNair would be his last. He, along with six other NASA astronauts, were aboard the Space Shuttle Challenger when it exploded 73 seconds after takeoff in 1986. Everyone on board the shuttle was killed.

McNair was 35 at the time of his death.

Today, the building that housed the library in South Carolina where McNair was refused books as a child is named in his honor.

5. Bessie Coleman

Bessie Coleman broke down barriers both on the ground and in the sky.

Coleman was inspired to become an aviator at 27 after her brother, a World War I veteran, teased her that women in France were superior because they could fly. Despite her drive, Coleman was denied from flight schools in the U.S. because she was Black and a woman.

Determined to become a pilot, Coleman began learning French, before leaving for Paris to pursue her dream.

In 1921, Coleman became the first African American woman to earn a pilot’s license, as well as the first African American aviator to hold an international pilot's license.

Coleman returned to American, and on September 3, 1922, she made the first public flight by a Black woman in the U.S. in a plane she borrowed.

Coleman worked her way into barnstorming, a form of entertainment involving aerial stunt tricks. In April 1926, while practicing for a performance in Florida, Coleman's plane began nosediving at 3,500 feet. Coleman was not strapped in for the flight, and she was thrown from the aircraft and killed. The mechanic onboard with her was killed in the ensuing crash.

Before her death at 34, Coleman was saving money to open a flight school to teach other Black women to fly.

Coleman's life and work inspired generations of astronauts and pilots. Dr. Mae Jemison, the first African American woman in space, carried Bessie Coleman’s picture with her on her first mission in September 1992.

6. Alexa Canady

Born in Lansing, Michigan in 1950, Dr. Alexa Irene Canady broke both gender and color barriers when she became the first African American woman neurosurgeon in the United States in 1981.

While majoring in zoology at the University of Michigan, Canady became interested in medicine after attending a summer program on genetics for minority students.

After receiving her B.S. in 1971, Canady graduated cum laude from the College of Medicine at the University of Michigan in 1975.

While she was initially interested in internal medicine, Canady later developed an interest in neurosurgery. She was accepted as a surgical intern at Yale-New Haven Hospital in 1975. She was the first Black woman to be enrolled in the hospital's internship program.

"I made it to Minnesota for residency, and before I knew it, I was a neurosurgeon. I had achieved my dream," Canady wrote in a personal essay for the University of Michigan. "And that’s all it was to me, because being the 'first' anything was never my goal."

Canady said that it was not until she began talking to people in the community that she realized the importance of her milestone.

"One, it was important for the children, who would no longer see neurosurgery as yet another world that they couldn’t belong to. That’s the side everybody appreciates," she said. "And that was equally important in changing society’s expectations. So while being first wasn’t important to me, it was important for many others."

Dr. Canady served as the chief of neurosurgery at the Children’s Hospital of Michigan from 1987 until her retirement in June 2001.

7. Robert Smalls

Robert Smalls was only in his early 20s when he risked his life as a Black, enslaved man in the U.S. South to sail his family to freedom.

After unsuccessfully attempting to buy his family's freedom, Smalls, a maritime pilot, devised a daring plan.

On a moonlit night in May 1862 during the Civil War, Smalls and a crew of fellow enslaved people stole the U.S.S. Planter, one of the Confederacy’s most crucial gunships, from its wharf in the South Carolina port of Charleston.

Smalls and his crew snuck their families aboard the ammunitions ship and began the treacherous journey to Union waters.

In order to pass unnoticed through the Confederate harbors, Smalls copied the ship captain's uniform and memorized his hand signals.

Smalls and the crew delivered the vessel, carrying 16 passengers, into free waters, and handed it over to the Union Navy.

Smalls' intricately coordinated escape astonished the world. Smalls was hailed as a hero in the North, and helped lobby President Lincoln to allow Black men to enlist in the Union Army. After the war, he served in the U.S. House of Representatives.

8. Gordon Parks

Gordon Parks was a Black American photojournalist, musician, writer and film director who is known for breaking the "color line" in professional photography.

"I saw that the camera could be a weapon against poverty, against racism, against all sorts of social wrongs," said Parks, who was born in Kansas in 1912. "I knew at that point I had to have a camera."

A self-taught photographer, he was the first African American staff photographer for "Life" magazine, and took photos of many notable figures in history throughout the years.

He was the first Black man to produce and direct a major motion picture, paving the way for Black directors after him. In 2000, he won The Congress of Racial Equality Lifetime Achievement Award.

9. Marian Anderson

Marian Anderson was an American contralto, meaning that she possessed a very low range in her vocal register. She was famous for performing a wide range of music, including opera and spirituals.

Anderson was born in South Philadelphia in 1897. Her talent was apparent from a young age, so much so that her church congregation raised a “Marian Anderson’s Future Fund" to support her performances and vocal training.

She became a star in Europe, debuting at the Paris Opera House in 1935, and performed at Carnegie Hall upon her return to America. The next year, she was invited to perform at the White House, the first African-American performer to do so.

For many years in Anderson’s career, she wasn’t allowed to perform in front of integrated audiences.

She was denied the opportunity to perform at Constitution Hall in 1939; outraged, First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt arranged for her to perform a concert on the Lincoln Memorial steps. 75,000 people attended Anderson's performance at the Lincoln Memorial on April 9, 1939.

In 1955, Anderson became the first African-American singer to perform at the Metropolitan Opera.

She gave her last performance at Carnegie Hall in 1965, before settling on a Connecticut farm with her husband until her death in 1993.

10. Jane Bolin

Jane Bolin broke many boundaries in her life, but perhaps her most famous is being named the first Black woman judge in America in 1939. (This is after she was the first Black woman to graduate from Yale Law School, and the first to gain admission to the New York City Bar.)

She fought against racial discrimination within the legal system; one of her many accomplishments as a Family Court (formerly the Domestic Relations Court) judge was changing the system so that publicly funded child care agencies had to accept children without discriminating based on race or ethnicity.

She served as a judge for 40 years and only retired reluctantly when she hit the mandatory retirement age of 70. After retiring, she volunteered as a reading tutor at New York City public schools and went on to serve on the New York State Board of Regents.

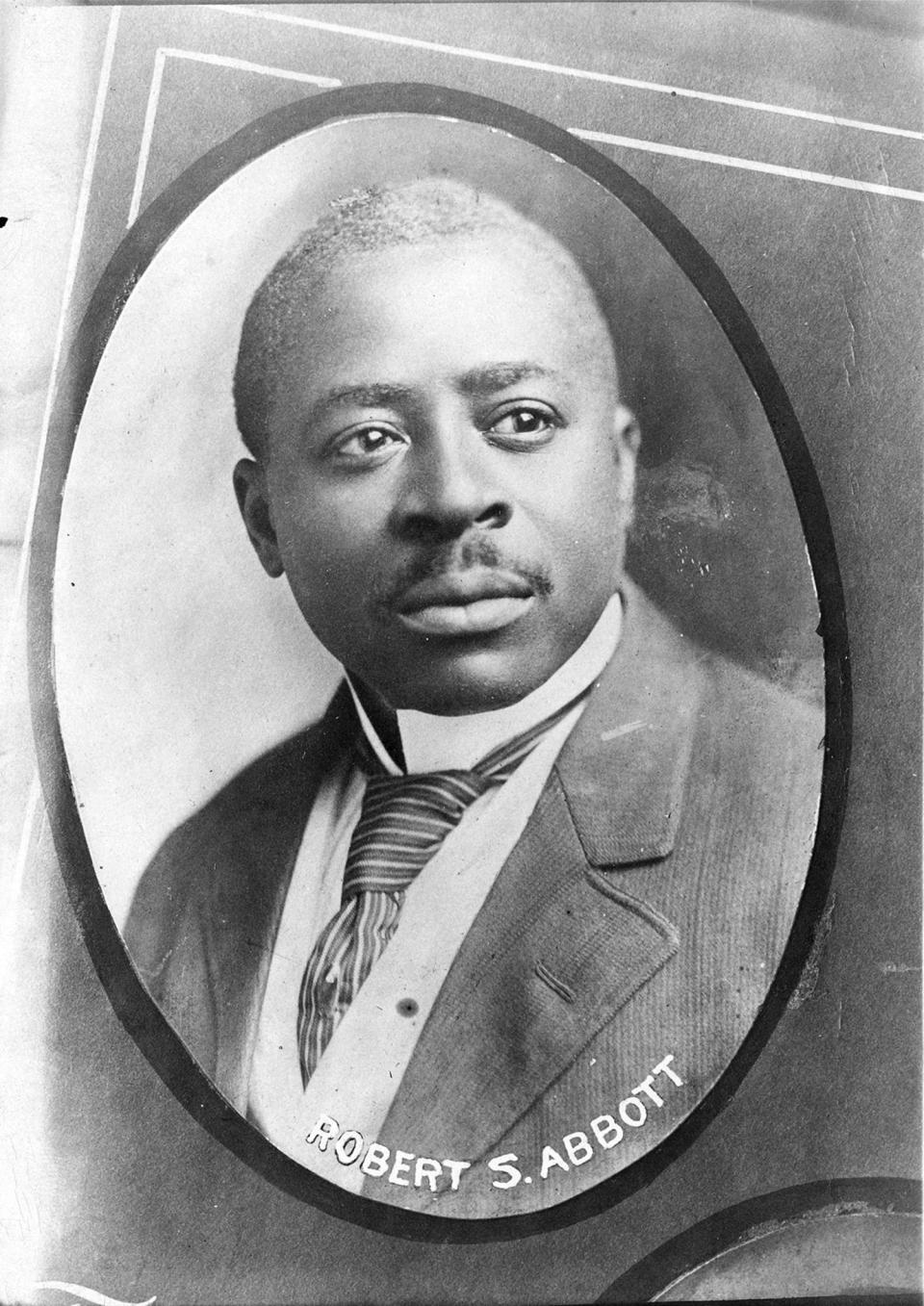

11. Robert Sengstacke Abbott

Born in Georgia in 1870 to parents who had once been enslaved, Robert Sengstacke Abbott was an American journalist, attorney and editor.

Though Abbott graduated from Kent Law School in Chicago, he was discouraged from practicing law from a fellow African-American attorney, who advised him that he was “too dark” to be successful in the field. Instead, Abbot drew on his bachelor's degree in printing from Hampton Institute (now Hampton University) and decided to pursue journalism.

In 1905, he founded the Chicago Defender newspaper. The Defender became one of the nation’s largest and most influential Black newspapers, and its circulation grew from 50,000 copies in 1916, to 125,000 in 1918, and to over 200,000 in the 1920s.

Through the newspaper's success, Abbott became one of the nation's first African American self-made millionaires.

The Defender both reported on and encouraged the "Great Migration," the massive movement of Black Americans from the U.S. south to cities in the North.

Abbott fought against Jim Crow laws and promoted the anti-lynching slogan, "If you must die, take at least one with you.”

This article was originally published on TODAY.com