5 who survived cardiac arrest describe what they saw and heard in their near-death moments

Every year, more than 350,000 people have a cardiac arrest outside of a hospital. Few survive. While many people who have been resuscitated have no memories of the experience, a recent study suggests others recall something, whether it’s a vague sense that people are around them, or more specific dreamlike awareness.

Unlike a heart attack where people are awake and the heart is still painfully beating, those in cardiac arrest are always unconscious. They have no heartbeat or pulse and need CPR urgently. In essence, they have “flat-lined” and are so near death there is no activity on electronic monitors.

What a near-death experience is has never really been defined. Researchers have been trying to explore what’s happening when a patient’s heart stops to see if there are themes or patterns of consciousness.

“There is an assumption that because people do not respond to us physically, in other words, when they’re in a coma, that they’re not conscious, and that’s fundamentally flawed," said Dr. Sam Parnia, a pulmonary and critical care specialist at NYU Langone Health, and the lead author of the recent study.

To find out more about the experiences of the few survivors who have a sense of consciousness during heart-related near-death events, NBC News connected with participants in the NYU Langone research and others from the Cardiac Arrest Survivor Alliance online community, a program of the Sudden Cardiac Arrest Foundation, and the Near-Death Experience Research Foundation.

They shared what they saw, heard and felt during resuscitation, how their lives changed afterward and what they believe other people should know about death and dying.

"Calm, quiet, peaceful"

Greg Kowaleski, a father of three who lives in Ann Arbor, Michigan, was 47 and playing a pick-up ice hockey game when he collapsed on the rink. Fortunately for Kowaleski, a pediatric cardiologist who is a good friend of his happened to be there, skating for the opposing team.

Dr. Jeff Zampi determined that Kowaleski didn’t have a pulse and immediately began chest compressions. Using an automated external defibrillator, or AED, Zampi was able to shock his friend’s heart back into a normal rhythm.

Although the cardiac arrest was in 2021, Kowaleski still recalls the “incredibly vivid” memory he had while Zampi was resuscitating him. Kowaleski found himself boarding an airplane that was completely empty, the blue seats stretching out in front of him.

“The sun is really bright outside, like a beautiful day and I sit down next to the window in my seat, looking out on the tarmac,” he said.

“As I’m sitting there waiting, I hear somebody call my name,” he said. “It’s my friend Jeff.”

In the memory, Zampi told him he was on the wrong flight and needed to get off. “I got up and I followed him out of the plane,” he said. “And then as we’re getting off the plane, boom! I came back. I woke up.”

Since then, Kowaleski said he’s struggled a little bit with what exactly the experience meant.

“The place where I went, wherever it was, I will say it was extremely peaceful,” he said. “I don’t know that I’ve ever experienced anything so calm, quiet, peaceful.”

What he does know is that he doesn’t really fear death anymore.

“It’s not a scary, bad place to go, wherever I was.”

"There was no gender"

In 2016, Em James Arnold, a parent in New York City, had a cardiac arrest and was revived.

Arnold’s girlfriend started CPR, but the resuscitation lasted 90 minutes and required nine defibrillator shocks. A combined team of FDNY firefighters and FDNY emergency medical services crews responded to the 911 call, which was made by Arnold’s 12-year-old daughter.

During the near-death experience, the cardiac arrest survivor — who was assigned male at birth and now prefers they/them pronouns — had a profound and life-changing memory.

Arnold remembers traveling feet-first over an expanse of water, floating on what seemed to be a stone-like surface. Overhead was an endless sky, and Arnold felt completely safe, free of fear, and neither male nor female.

Arnold, now 53, has had gender dysphoria since about the age of 3 or 4, although they didn’t always know there was a name for the feeling that one’s gender identity doesn’t match the one registered at birth.

“For me, that was like a lifelong puzzle," Arnold said. "And then, when I go into cardiac arrest and I’m in that water, there was no gender, so there was no assignment there. It allowed me to embrace that of myself.”

After waking from a three-day coma and a long hospitalization, doctors gave Arnold an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator, or ICD, a battery-operated implanted device that can shock the heart if necessary. Two years later they had surgery to repair a damaged heart valve.

After the experience, Arnold began emerging out and presenting as mixgender/transgender and, soon after, married their girlfriend.

“She’s the one who walked me through this, as she constantly says to me, be yourself, be yourself, just be yourself,” Arnold said. “That’s the hardest thing for anybody to do.”

The couple has a new baby, now 8 months. The cardiac arrest “helped me understand that gender is nothing,” Arnold said.

Like opening your eyes in a cave

Zach Lonergan, a 32-year-old scientist who lives in Pasadena, California, was regularly logging 15- to 18-mile runs with his friends as they prepared for the Los Angeles Marathon.

As part of the training, they all decided to run the Rose Bowl Half Marathon.

“We’re like, oh, 13 miles for a half marathon is no big deal,” Lonergan said.

However, when race day came in January, Lonergan wasn’t feeling well.

“Of course, I ignored my symptoms and decided to run a really fast race,” he said.

Despite feeling tired for the last few miles, he crossed the finish line. When he went to pick up his medal, he collapsed.

Without a pulse or heart beat, emergency workers performed CPR and shocked Lonergan's heart twice.

Lonergan doesn’t remember the collapse.

He does recall being awake and aware in a dark place that was unfamiliar, describing it like opening your eyes in a cave.

“It felt strange, but at the same time, it was the most peaceful time of my entire life,” he said. “In this darkness, I felt extremely warm, and extremely peaceful.”

After he was resuscitated, doctors gave him an ICD implant that would shock the heart, if necessary.

After he recovered, Lonergan did feel some anxiety, especially when it came to running. However, he also recalls it being a time of “prolonged peacefulness.”

Grateful to be alive, he no longer feared death. He took a “reunion tour” to reconnect with friends he hadn’t seen in years.

“You only get one life and you have to cherish the people you have around you,” he said. “I think that’s been the biggest gift that I’ve gotten.”

"All-surrounding sense of love"

Dr. Melinda Greer, 65, was being evaluated for chest pain at a cardiac intensive care unit when her heart stopped. Greer, a retired pediatrician in Tahlequah, Oklahoma, had asystole, a failure of the heart’s electrical system which causes the heart to stop pumping, or flat-line.

That was 10 years ago. She is finally opening up about what she feels was a positive experience.

As the nurse was performing CPR on her, Greer saw an “incredible white light” and felt “an incredible all-encompassing, all-surrounding sense of love.”

She felt like she had returned to a “place that felt like home to me, and I was back amongst a group of what I can only call beings, because we weren’t physical, that I considered my group.”

It was “a wonderful experience," she said. "I really was angry when they brought me back.”

After Greer left the hospital, she decided to retire early, focusing on creative pursuits and new experiences, rather than acquiring things. She encourages people to get more involved in the “positive aspects of living in a beautiful world.”

“Feel the wind, get out in nature, take off your shoes and socks and put your feet firmly on the ground and just listen to that inner voice, that’s what I would recommend," she said. "I wish I’d done it long ago.”

"I knew I could not leave them”

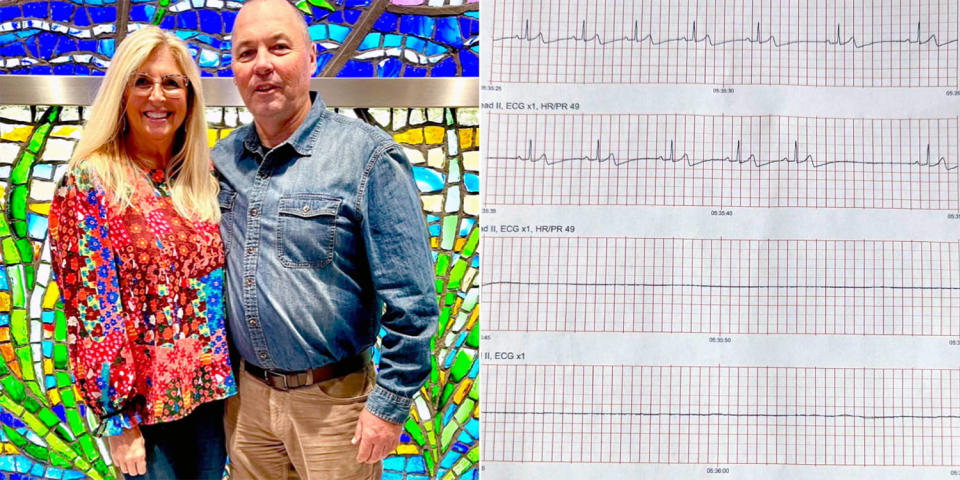

Connie Fuller, 55, lives in Warrior, Alabama, just north of Birmingham. In 2020, Fuller was diagnosed with ovarian cancer. In 2021, she and her husband made the hard decision to sell their swimming pool business to spend more time together. But the day of the sale was particularly stressful, and she started having chest pain.

She was admitted to the hospital for observation, although tests had ruled out a heart attack. It was at this point that she developed bradycardia, an abnormally slow heart rate, and her heart stopped.

Fuller doesn’t remember when the nurse started CPR. She didn’t feel any pain, although she found out later that the nurse broke her sternum and several ribs, a common occurrence during CPR.

“I love her, she saved my life," Fuller said.

What Fuller does remember is hearing her husband’s voice when he came back into the room.

“We started dating when I was 14, he was 16," she said. "He sounded like that little 16-year-old boy. That was the voice that I heard."

She feels that her husband’s voice helped pull her back into her body, as the medical team worked to revive her.

“I do remember thinking, this feels so good and so peaceful and it’s so calm and there’s no worries here,” she said. “But at the same time, I remembered my husband and my daughter and I knew I could not leave them.”

Based on her experience, Fuller advises family members to talk to patients, even when it seems they are dying.

“If it’s safe, and possible — allow the family members to be there to talk to the patient,” she said.

Fuller, who believes in God, wondered why she didn’t have experiences that are more like the traditional concept of heaven.

“Psychologically it’s been a lot to handle,” she said. "I thought, why wasn’t I in heaven? Why didn’t I see my relatives? Why didn’t I see the white light? You know, why didn’t that happen for me?”

Fuller turned out to have takotsubo cardiomyopathy, or broken heart syndrome, which is a weakness of the heart muscle that can be caused by severe stress.

“I thought at that time I had wasted my heartbeats worrying about a swimming pool store," Fuller said. "That’s when I prayed and I begged God, please give me one more chance to not waste any more heartbeats on something that’s not important. I won’t. I will not do that again.”

This article was originally published on NBCNews.com