5 years after her son was murdered at the Red Rose, Pearl Wise is still shattered by loss

Pearl Wise vividly remembers the conversation with her son, Chad Merrill.

She can’t quite remember when it occurred, or the exact circumstances. The past few years, she has searched her memory for those details, but they fail to surface. She remembers the words, what her son said, and how they came back to haunt her one early July morning five years ago.

She remembers that her son once told her, “I feel like I’m not going to live long.”

Pearl responded, “What do you mean?”

He said he couldn’t explain it. He doesn’t know where it came from, or how he came to it. “It’s just a feeling I have,” he told her.

Pearl wasn’t sure what to make of it. Chad was a happy young man. He was working as a mason, after trying a brief stint at a desk job and finding that he preferred working outdoors with his hands, building and creating things. He was a slight man, thin, with a slight goatee. He had friends and girlfriends, and he loved and cared about people. She had no idea why he believed that.

Pearl told him, “Then, you just have to be careful.”

And she put it out of her mind.

She hadn’t thought about the conversation for some time, consigning it to the deep recesses of her memory.

It came back to her in the single-digit hours of July 21, 2018, as she and her husband drove to York Hospital. There were a lot of thoughts crossing her mind, none good. But her memories of that conversation dominated her thoughts.

Just a few minutes earlier, she had been sleeping when her husband woke her and told her, “Chad’s been shot.”

An epidemic of violence

Those are words no parent wants to hear. But more and more, parents, siblings, children and friends and families are hearing them, the result of the gun violence epidemic in this country.

While, overall, statistics bear out that gun violence is down from its highest levels in the 1970s, at least on a per capita basis, the overall number of deaths is at its highest level ever, reaching 48,830 in 2021, the last year for which figures are available − an increase of 23 percent since 2019, before the COVID-19 pandemic, according to a study by the Pew Research Center. Fifty-four percent of those deaths in 2021 were suicides. Forty-three percent, or 20,958, were homicides.

In Pennsylvania, the number of homicides committed with firearms increased by 12 percent from 2010 to 2019, according to the Pennsylvania Commission on Crime and Delinquency. In the first two decades of this century, 28,990 people lost their lives to gun violence in the commonwealth.

One of those was Pearl Wise’s son.

Chad wasn't just a number. And five years after his death, his mother still grieves, a deep grief that has led her to advocate for the rights of crime victims, speaking at vigils and lobbying for laws to make the criminal justice system more accountable to victims and survivors of crime.

"It has been very therapeutic," Pearl said. "It has given me something of a purpose, something to figure out who I am. I'm not the person I was."

'It never goes away'

Early that Saturday morning in June 2018, Pearl became a member of a club that no one ever wishes to join − those who have lost loved ones to gun violence.

It’s a lifetime membership. There is a lot of talk about “closure,” mostly when a murderer is arrested and convicted, but Bev Warnock, national director of the Cincinnati-based Parents of Murdered Children, said there is no such thing. “It’s constantly in your life,” she said. “It never goes away.”

Its membership expands week by week. Just over the long Fourth of July weekend this year, 20 people were killed and 126 injured in 22 mass shootings, including incidents that occurred in Philadelphia, Baltimore and Fort Worth, Texas, according to the Gun Violence Archive.

While Parents of Murdered Children doesn’t take a stand on “particular issues,” choosing instead to focus on families that have lost loved ones, Warnock said, “It’s just scary that you can’t go to a parade, or a grocery store, or a block party without worrying that someone will bring a gun out. It’s too out of control.”

His belief was to become reality

Chad Merrill was born in York on March 30, 1993, the second-born son of Pearl and her ex-husband, Richard Merrill.

He loved sports, his favorite being basketball. His mother said she could always find him on the basketball court, shooting hoops or playing. When he played organized basketball, he wore number 23 in honor of his idol, the legendary Michael Jordan.

Chad’s real hero, his mother said, was his brother Richard, who was six years older than him. After Chad’s death, Pearl found a folder containing essays he had written while in school. One of them was an assignment to describe his hero, and he named Richard. He wrote that some kids from down the street were bullying him, and Richard stood up for his kid brother. Chad never forgot that, Pearl said. He and Richard may have had differences and, like brothers, would skirmish, but Chad “always looked up to Richard,” Pearl said. Richard standing up to bullies and trying to make peace was a lesson that stuck with him.

Chad was a good friend, Pearl said, and was incapable of saying no to a friend in need. “He would loan money to friends anytime,” she said. “It didn’t matter whether he had bills to pay.”

After graduating from Eastern York High School, he went to York Technical Institute to study computer-assisted design. He did well in school and upon graduation got a job designing rebar reinforcement systems for construction projects. It didn’t take long before he realized he had made a mistake. “Sitting at a desk all day,” his mother said, “was too boring for him. It just wasn’t him. He was a hands-on person.”

A friend had a brother who was a mason and introduced Chad to him. He found his calling. He picked up the work quickly. “If someone showed him something hands-on,” Pearl said, “he could do it.” He liked working with his hands outdoors, and he was a hard worker.

After a hard week of work, Chad had a Friday evening routine. He’d come home to his mother’s rural home in Lower Windsor Township, clean up, have dinner and then go out. His first stop was the Tourist Inn, on East Market Street by the Route 30 interchange east of York, where he would have a beer with his boss and discuss next week’s work schedule and get paid.

From there, he’d head out to his local hangout, the Red Rose Restaurant and Lounge, to meet up with one of his friends, Jerrell Grandison-Douglas.

That Friday – July 20, 2018 – when Chad was getting ready to leave his mother’s house, she told him to be careful, that she loved him.

He paused and looked at his mother. Pearl thought it was strange.

“It was like he knew what was going to happen,” she said.

Pearl felt, for some reason and in retrospect, that it was the last time she’d see her son alive.

She can’t shake that feeling, that her son’s belief that he wouldn’t live that long was about to become reality.

A typical Friday night ends tragically

The Red Rose is kind of a rural gathering place, about halfway between Hallam and Wrightsville on the old Lincoln Highway. It is known as a friendly place, with inexpensive food and drink, and for its pool tables. The bar hosted pool tournaments and league play and was the venue for the pool competition in the first responder Olympics a few years back.

For Chad, it was his hangout, the place where he could spend a Friday night with friends, some of whom he had known since high school. That’s where he met one of his best friends, Jerrell.

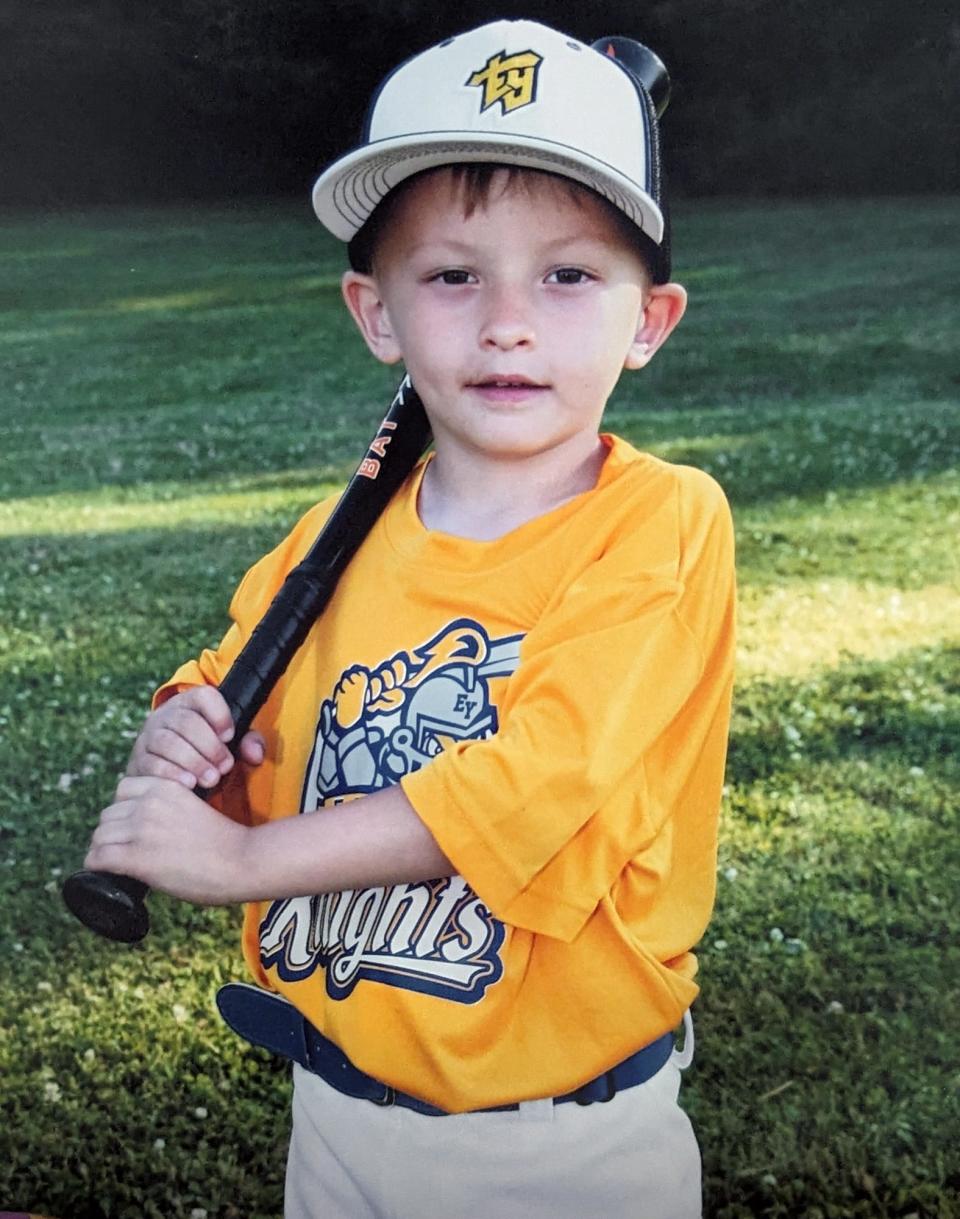

Jerrell went to Central York – his family was originally from Brooklyn – and he and Chad hit it off when they first met. Later, when Chad had a child, a son, he and Jerrell bonded over being fathers. Jerrell had a daughter, Aurora, who was 2 two when Chad’s son Layton was born.

Layton was the result of a one-night stand, Pearl said. His mother was an addict, and Chad was responsible for his son’s well-being, a responsibility he took seriously, his mother said. But he was young, and a single father, and he needed help.

He found that with Jerrell. “We would talk about our kids, and he’d ask for advice,” Jerrell said. Chad impressed Jerrell with his dedication to his son and his desire to be a good father. They were a lot alike, both working men – Jerrell worked as a machinist – and they were young fathers.

They were sitting at the bar that Friday night, or early Saturday morning, when James Saylor entered.

Saylor had spent the day drinking, mostly Long Island iced teas, a strong drink composed mostly of liquor served in a pint glass. He had already been thrown out of one bar, the Glad Crab, for being drunk and disorderly. From there, according to court documents, he went to a woman’s house. She really didn’t know Saylor – he was her postman in Wrightsville – and had been asleep when he arrived drunk. She told him to leave. And then, at about 1 a.m., he wound up at the Red Rose.

When he saw Jerrell at the bar, he was not pleased and belligerently shouted about people of the N-word race being admitted to the establishment. Jerrell is Black. He tried to let it roll off his back. Jerrell offered to buy Saylor a drink, but Saylor wouldn’t have anything to do with it, saying that he doesn’t drink with N-words. Jerrell remained calm. As he said later, “I’ve dealt with this all my life.”

Chad came to his friend’s defense and told Saylor to cool it. By then, the bar’s owner, Nick Spagnola, became aware of what was happening and threw Saylor out.

Once outside, Saylor pulled a .45 semi-automatic pistol from the waistband of his shorts and took a potshot at the bar. He got to his pickup truck and was getting ready to leave when an Uber driver who had been summoned to the bar partially blocked his way.

Chad had gone outside to see whether everything was OK. He saw Saylor in his truck and approached him, wanting to talk to him, to make peace, to calm things down, Jerrell said later.

As Chad approached the driver’s side window, Saylor pointed his .45 at him and shot him in the chest, an act that was captured on surveillance video.

Chad fell to the ground.

Saylor backed out of his parking space, struck the Uber driver’s car and fled.

He was arrested later at his parents' house nearby.

Chad was taken to York Hospital, where he was pronounced dead. He was 25. He left his mother, his stepfather, his father, three brothers and nephews and nieces.

![Jerrell Grandison-Douglas sits for a portrait after recalling the night that his friend, Chad Merrill, was shot for defending Grandison-Douglas from racial slurs. "Whether the story is told or not, you're still going through [racism]," Grandison-Douglas said. "And you do whatever you can to protect yourself, whether it's looking over your shoulder at all times or making sure you can see everybody in the bar, or making sure there's no one behind you. It's just something that's ingrained into your being, and you just do it subconsciously. You don't even think about it anymore."](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/3H01ox5uYMui3yG6Vr8yuA--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTY3Nw--/https://media.zenfs.com/en/york-daily-record/96e38a155f32651c693cf4a03914981d)

'I never cried'

The next few days were a blur for Pearl.

“I guess I was in shock,” she said. “I just went through the motions.”

The funeral felt like an out-of-body experience. “Friends of his came to me and cried on my shoulder. I was just sitting there looking at my boy in that casket. I never cried.”

In a church filled with maybe 200 people, she felt alone.

She needed to know

Not long after, Jerrell got in touch with Pearl. She had never met her son’s friend. She had heard about him from her son, but they never met. Jerrell felt obligated to tell Pearl what had happened. “I felt she needed to know, even if it hurt, to give her some clarity,” Jerrell said.

She could tell that Jerrell was hurting, that he blamed himself for Chad’s death, merely by being Black at the bar. They talked for a while. A bond was formed. Over the five years since, they have kept in touch, a relationship formed over the death of a young man who meant so much to them.

Watching her son's murder

The trial was also a blur, she said. She had no experience with the criminal justice system, and it was confusing at times. At one point, she was told that the prosecutor was going to screen the video of her son’s death. The victim’s advocate from the district attorney’s office offered to screen it for her privately, or to allow her not to be in the courtroom when it was played. She declined. She wanted to see it in the courtroom.

She thought she was prepared for it.

But she wasn’t.

In the abstract, it was something on a television screen.

In reality, she said, it was watching her son being murdered. It was two minutes long. At the moment Saylor shot her son, she could feel her heart being crushed. She gasped and began crying, earning an admonition from the judge against emotional displays in the courtroom.

At the conclusion of the trial, Saylor was found guilty of first-degree murder and sentenced to life in prison without the chance for parole.

It was a moment of closure, at least according to the conventional wisdom.

For Pearl, it wasn’t.

Saylor was still alive.

Her son was dead.

Trying to find forgiveness

Jerrell keeps in touch with Pearl to this day. His daughter and Chad’s son are friends. And he feels that he can understand what Pearl is going through; they share something that nobody else can understand. “There’s no need to explain,” he said. “I can talk to her about things. There’s a level of understanding. She helps relieve some of the negative feelings I have about that night.”

Five years on, Jerrell still thinks about Chad and what happened almost daily. He still carries the weight of guilt. He relives that night and questions how things could have turned out differently, an alternate reality in which Chad is still alive. He struggled to find a lesson, or any meaning, in what happened that night.

“I didn’t physically do anything that night,” he said, “but my presence caused a very bad situation to happen. I always like to take accountability for things. If I wasn’t there, Chad would have been able to walk away and be home with his family.”

He struggles to find forgiveness – forgiveness for himself, for his mere presence causing the death of a man who was a good friend.

Previously: 'This wouldn't have happened if I wasn't black': Red Rose victim's friend copes with loss

'A leap of faith'

The first year after Chad died, Pearl was “totally numb,” she said.

“I knew my son was dead, but I hadn’t accepted it,” she said. “I knew he was gone, but it hadn’t hit me yet that he was gone. I was going through the motions. I was just doing what I had to do.”

She spoke at events advocating for victim’s rights, and at one such event, she met Aswad Thomas, the national director for the Crime Survivors for Safety and Justice advocacy group. He asked her to become involved in the organization, saying it would be helpful for her as she tries to find meaning in what happened to her son.

“She took a leap of faith,” Thomas said. “My impression of Miss Pearl was that she was very quiet, but once she started to open up and talk about her experience, she was outspoken. Miss Pearl is one of my favorite people. She’s a tremendous human being.”

In June, she joined hundreds of other crime survivors in Harrisburg for a vigil and a day of lobbying the state Legislature for laws to afford crime victims more access to counseling and more representation in the criminal justice system.

She never thought she’d be doing something like that. Her work with the advocacy group allows her to spend time with others who have an understanding of her experience. But still, she feels alone. Every person has a story to tell, she said, and they are all as different as they are the same.

She has met Marisa Vicosa, the woman whose estranged husband, a former Baltimore County cop, killed their two daughters and his girlfriend before killing himself. "I just hugged her and told her that I'm here for her," Pearl said.

Marisa Vicosa speaks: Satanic bible found in Vicosa's basement: 'My husband was becoming more and more evil'

But even though she knows people who have been through worse, she said she still feels alone.

“I’ve been through a lot in life,” she said, “but this is the worst thing ever. I would not wish it on anybody.”

'Life as I knew it is over'

She now has custody of her grandson, Layton, whose mother died of an overdose two years ago. Layton is five years old now, born the February before his father’s death. He looks just like Chad, Pearl said. He is doing very well, and one day, when he can understand, she wants him to know everything about his father. She had filed a wrongful death and negligence lawsuit against the owners of the Red Rose and the Glad Crab but dropped the case after a year.

Still, every day can be a struggle.

“I’m not the person I was,” she said. “I still feel the hole in my heart. Life as I knew it is over. I'm just starting over.”

She still doesn’t sleep well. She lost her job managing a convenience store. She started a tax business but couldn’t concentrate on it and closed it up. She has a hard time remembering things. She plays that night over and over again in her mind, imagining ways it could have ended with her son coming home. “There are so many ways my son did not have to die that night,” she said.

Above the mantle of the fireplace in her family room is a shrine to Chad. There are photos and knickknacks, a basketball, things that remind her of her son’s life. Among them is a commendation from the Pennsylvania Human Relations Commission, honoring Chad posthumously for his courage in the face of racism.

The room has a large window that looks out into the backyard. The yard is dominated by a playground that Chad helped build for his son. Pearl always told him, “This place will be yours one day.”

Pearl gazed out the window and pointed out the things Chad helped build. She is wistful and a slight smile appears quickly as she recalls working on the yard with her son.

The smile disappeared.

“I miss him so much,” she said.

Columnist/reporter Mike Argento has been a York Daily Record staffer since 1982. Reach him at mike@ydr.com.

This article originally appeared on York Daily Record: Mom of the Red Rose murder victim tells how grief led her to advocacy