50 years ago, Tennessee football made sure the world was ready for Condredge Holloway

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

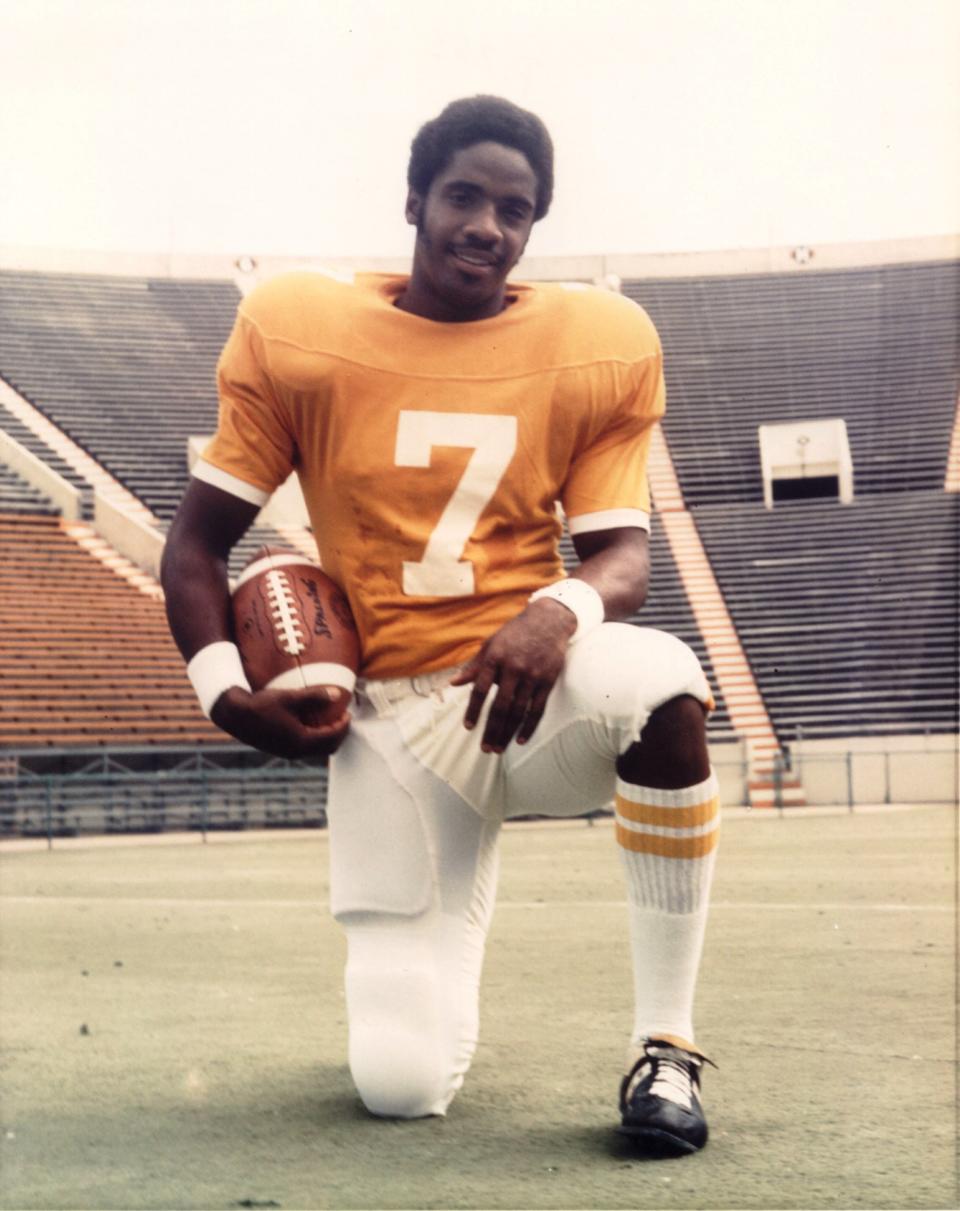

Condredge Holloway, a wide-eyed 18-year-old Tennessee quarterback, strolled into Georgia Tech's stadium on a day commemorated by a statue 50 years later.

It was Sept. 9, 1972.

The setting seemed special, albeit with a time-capsule quality.

Tennessee players ate ribeye steaks and Jell-O as a pregame meal. They wore new orange jackets and brown trousers, donated by a Haggar retailer in Knoxville so the team could make a classy impression before its national television game.

ABC cameras set up around the stadium, preparing for the moment when the broadcast would shift quickly from the Munich Olympics to the Vols’ season opener at Georgia Tech.

Americans were glued to their TVs, but not to see Tennessee football.

It had been only three days since a terrorist attack left 11 Israeli Olympic athletes dead in Munich.

And the most controversial Olympic basketball game in history would be played during the Tennessee-Georgia Tech game. It featured the infamous ending when the Soviet Union was given three chances at a game-winning play as time expired, only to fail twice and succeed on the third attempt to beat Team USA.

But that wasn’t as vital to the 8,000 Tennessee fans – some of them wearing “Don’t Like Tech” buttons – who traveled to Atlanta to see Holloway’s historic debut firsthand.

A week later, almost 10 times that size crowd would see him play in the first game under the lights at Neyland Stadium, where his statue now stands.

Tennessee fans of a certain age recall the day Holloway became the first Black quarterback to start in the SEC. Many more know of Holloway highlight-filled career that earned him the nickname “The Artful Dodger.”

Numerous books have chronicled it. And ESPN featured his journey in the documentary, “The Color Orange: The Condredge Holloway Story,” produced by country music star Kenny Chesney, a Knoxville native and lifelong Holloway fan.

But the events that led Holloway to that historic moment aren’t known quite as well.

It involves a surprisingly spurned pro baseball career, a comical quarterback competition and a year of preparing Tennessee for a Black quarterback.

The 68-year-old Holloway, who lives a private life in Knoxville, declined an interview request through a Tennessee spokesperson. But Knox News archives and first-hand accounts tell the story of Holloway during the critical year before he became a household name and a Vols legend.

BLAST FROM VOLS PAST: Bryce Brown — Lane Kiffin's No. 1 recruit — answers what-if questions 12 years later

PEYTON MANNING: His Hall of Fame origins were evident in freshman year at Tennessee

Holloway’s signing with Tennessee was a footnote

Holloway was a local celebrity in Knoxville before most fans saw him play a varsity football game.

In 1971, NCAA rules did not allow freshmen on the varsity team. But before he played that game against Georgia Tech to start his sophomore season, Holloway’s name had already appeared in 86 Knoxville News Sentinel articles.

However, his stardom wasn’t immediate.

On Dec. 17, 1970, Holloway’s signing was upstaged by hometown hero Neil Clabo’s commitment to Tennessee. The Farragut running back was a Parade All-American and the No. 1 prospect in Tennessee.

Clabo chose Tennessee over Auburn, which was celebrated as a major recruiting victory. The last three sentences of the article mentioned that Holloway, an undersized 16-year-old quarterback from Huntsville, Alabama, also picked the Vols over Auburn.

Clabo certainly wasn’t a bust. As a punter, he lettered three years and earned All-SEC honors in 1974. Then he punted in the NFL for three seasons, which included a Super Bowl appearance with the Minnesota Vikings.

But Clabo would seldom steal the spotlight from Holloway again.

Holloway was drafted ahead of hall of famers

Holloway’s first hint of fame came because of baseball, and it was well deserved.

In the 1971 MLB Draft, Holloway was picked No. 4 overall by the Montreal Expos out of Robert E. Lee High.

Notably, he was the second of 10 shortstops selected in the first 30 picks. Future hall of famers George Brett and Mike Schmidt were the ninth and 10th shortstops picked, but they moved to third base.

Another hall of famer, Red Sox outfielder Jim Rice, was drafted 11 picks after Holloway.

The 107th shortstop drafted in 1971 was Notre Dame quarterback Joe Theismann. Of course, Theismann stuck with football, but most people thought Holloway would choose the opposite path. A future Pulitzer Prize winner was among them.

In 1971, Mike McKenzie was a sports reporter for The Huntsville Times, covering Holloway as a high school star in football, basketball and baseball.

It was early in McKenzie’s 40-year sports writing career, which included a stint at Sports Illustrated and a role on a Pulitzer Prize winning team at the Kansas City Star. But in 1971, he was already a trusted source among sportswriters in the South.

McKenzie reported that Holloway was expected to spurn Tennessee for pro baseball. It set the tone for Tennessee fans who believed they’d never see Holloway in orange and white.

More than 30 years later, McKenzie was blamed for misleading Alabama fans in thinking Crimson Tide coach Dennis Franchione would not leave for Texas A&M. And then he left.

McKenzie, who wrote under the moniker “Writer Mike” for the infamous website CoachFran.com, was wrong about Franchione. He was also wrong about Holloway, but opting for pro baseball didn't seem far-fetched.

Holloway still played baseball at Tennessee. He earned All-America honors, an SEC batting title, a school-record 27-game hitting streak and had his baseball number retired.

Table tennis halted Holloway’s path to MLB

Bobby Majors, an All-America defensive back at Tennessee, told the News Sentinel during a 1971 preseason practice that Holloway had dominated his new football teammates in table tennis, a popular pastime in the dorm.

“I can beat most of the boys in pingpong,” Majors said. “But Holloway beat me, beat me bad. He’s quick.”

By then, it was an inside joke.

In June, Holloway broke off contract talks with the Expos to play ping-pong with Tennessee assistant coach Ray Trail.

Holloway, his mother and attorney met with the Expos scouting director. Initial reports said the offer was $50,000, but that figure grew to almost $100,000 in later reports.

Holloway was exhausted after three hours of talks. So he stepped away to play pingpong with Trail, who recruited him to play football for the Vols. They played for an hour, and Holloway never lost a match.

And he never returned to serious negotiations with the Expos.

Expos took the wrong tone with Holloway’s mom

Pingpong was an interesting anecdote, but Holloway’s mother was credited with steering him toward college.

Since Holloway was 17, an Alabama law required that a parent had to co-sign his contract. His mother refused because she valued his education over professional sports.

“Back then, we didn’t know that Condredge turned down baseball,” said a chuckling Eddie Brown, a sophomore when Holloway arrived. “We just knew his mom turned it down.”

The Expos’ tone in the negotiations may have influenced her decision, as well.

In 1962, Dorothy Holloway became the first Black employee at NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville. In 1972, she told Sports Illustrated the Expos took a racist approach in courting her son.

“A lot of people in baseball could use some schooling on a human relations basis,” Dorothy Holloway said. “They couldn’t or wouldn’t talk to me. They would go through his coach, and it reminded me of some old stereotype that you must go through a white to communicate with a Black because a Black doesn’t know how to talk or something. The University (of Tennessee) didn’t deal this way.”

How coaches prepared Tennessee fans for Black quarterback

Racism was certainly a part of Holloway’s life and football career.

In the ESPN documentary, Holloway said coach Bear Bryant “wanted me to come, but Alabama wasn’t ready for a Black quarterback.”

Instead, Holloway would’ve played defensive back for the Crimson Tide. He heard a similar plan from the New England Patriots, who picked him in the 12th round of the 1975 NFL Draft.

So Holloway went to the Canadian Football League, where he won two titles, an MVP award and induction into the CFL Hall of Fame as a quarterback.

In 1971, Tennessee coaches and reporters tried to prepare fans for Holloway’s arrival.

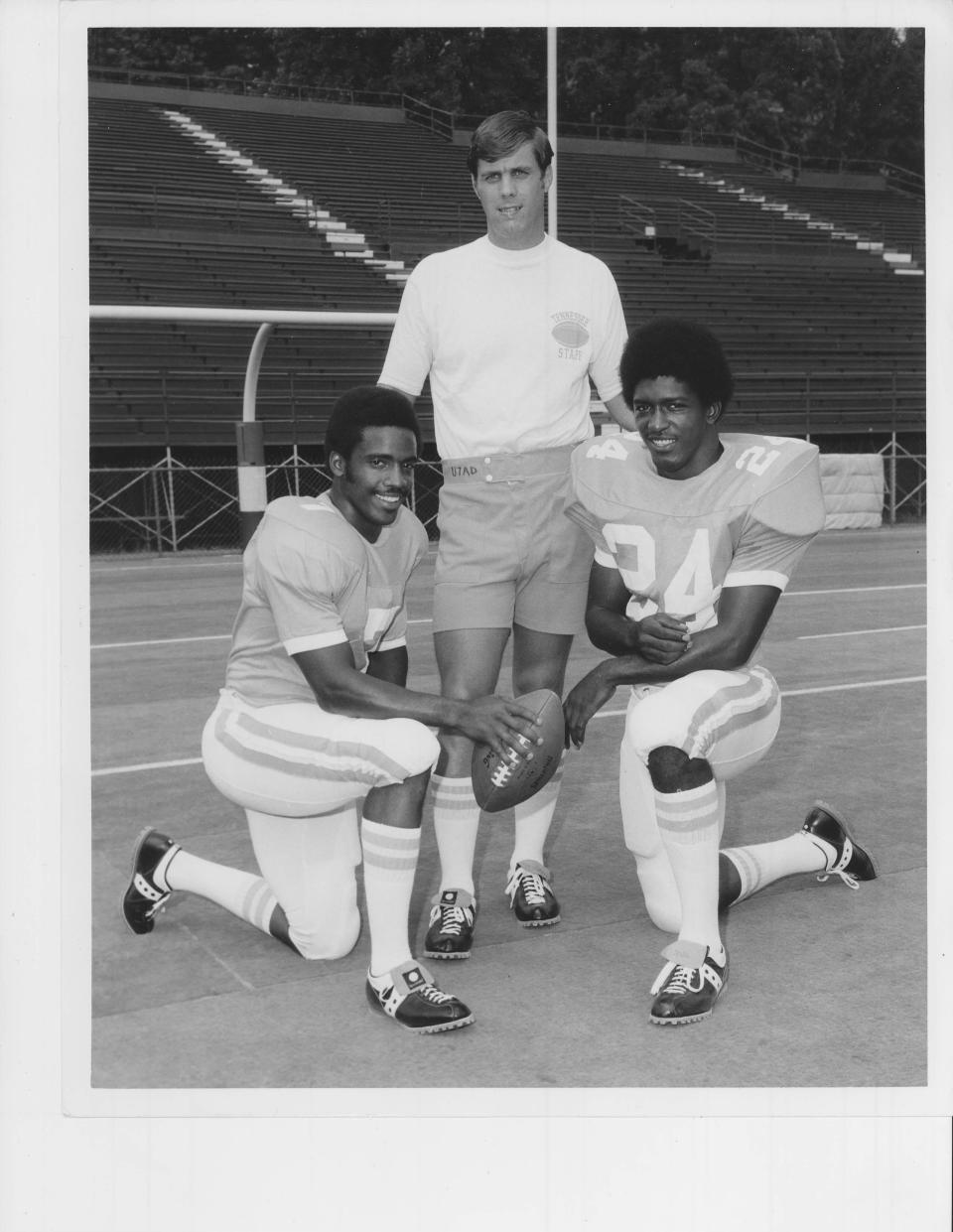

“Coach (Bill) Battle and Coach Trail, when they had media conferences, helped prep people to accept Condredge,” said Haskel Stanback, a Black tailback on the 1971 team. “They’d talk about him being a good kid from a good family.”

The Vols already had Black players. Wingback Lester McClain was the first in 1968. And linebacker Jackie Walker was an All-American and team captain when Holloway got to campus.

But adjusting to a Black quarterback was the next step for Tennessee and the SEC.

Reporters paved way for Holloway’s debut

Coverage of Holloway’s freshman year accentuated the quarterback’s humble personality and wide-ranging talents. He not only could dunk a basketball at 14, but he also played the trumpet and drums and planned to be a dentist after his playing career.

“The sportswriters, Marvin West (of News Sentinel) and those guys, would spend a lot of time in the locker room getting to know us pretty well,” Stanback said. “They would write positive things about Condredge.

“It wasn’t overkill. But it was a little bit above and beyond, and that helped.”

Racism was barely detectable in News Sentinel coverage of Holloway, although some phrases sound awkward by today’s standards. In an August 1972 story, Tennessee’s quarterback was introduced as a “handsome young black” in a United Press International wire story.

Two weeks before Holloway’s 1972 debut at Georgia Tech, a News Sentinel headline said “Condredge wins opener.” It referred to the first impression he made on the skywriters – a group of traveling sportswriters that served as a precursor to SEC Media Days.

They peppered Holloway with questions about race.

“I’m just a Tennessee Volunteer quarterback. I don’t feel I have to prove anything for my race,” Holloway said. “I’ll just go out and do the best I can. If a player has the ability to play quarterback, he gets a shot at quarterback. At least that’s the way it is at Tennessee.

“People here like Tennessee football. They don’t care if you’re Black or white.”

The article ended with the observation that “some of the writers almost applauded.”

Vols couldn’t keep Holloway secret

News of Holloway’s talent got out long before his first varsity game.

In 1971, Holloway practiced with the freshman team. But Battle routinely borrowed him on the scout team to impersonate the SEC’s best offensive players against the Tennessee varsity defense.

During the Auburn week, Holloway played the part of Heisman Trophy quarterback Pat Sullivan and All-America wide receiver Terry Beasley in the same practice.

“I remember thinking, ‘I’m glad I don’t have to play against Condredge on Saturdays,’ ” said Brown, an All-America defensive back for Tennessee.

During a 1971 freshman game, a Holloway-led squad was beating Alabama 36-13 late in the fourth quarter. Battle called from the press box and told his freshman coaches to keep Holloway and the first-team offense in the game.

Why? The News Sentinel suggested it had something to do with Alabama’s 32-15 win over the varsity Vols three weeks earlier, when Tide running back Johnny Musso scored a TD with 32 seconds remaining.

The freshman Vols didn’t score again. But Holloway was completing passes into the red zone when the final horn sounded. Battle knew he had a weapon for future seasons, and the word was getting out.

A week later, a record crowd of 31,300 fans attended Tennessee’s freshman game against Notre Dame at Neyland Stadium.

Officially, it was a fundraising event for the expansion of the East Tennessee Children’s Hospital. Unofficially, it was a chance for Tennessee fans to get a sneak preview of Holloway during the varsity team’s off week.

Holloway scored on an acrobatic run for the first TD in the 30-13 win. The play became a myth as the quarterback’s popularity grew. In the next day’s edition, the News Sentinel said Holloway turned a “cartwheel” on the 12-yard run.

A year later, Sports Illustrated described it like this: “He dived into the air from their 7 (yard line), was hit at thigh level by two tacklers on the 5, did a flip and landed on his back in the end zone.”

Who Holloway had to beat to start at quarterback

In retrospect, the quarterback competition before the 1972 season seems comical.

“It never really was a competition,” Stanback said. “Condredge just had to learn the playbook and get to his sophomore year. Then the competition was over.”

But there were several other options at quarterback, and Holloway dispatched each of them.

Chip Howard, a Knoxville native, and Dennis Chadwick moved from quarterback to wide receiver. Tommy Beaver, from Maryville, and Jim Richardson moved from quarterback to defensive back.

That thinned the herd early in 1972.

Holloway and Ed McDougal, a 6-foot-4 strong-armed passer, shared first-team reps to start spring practice. Dan Fletcher, a 5-11 sophomore, got the same opportunity in the Orange and White spring game.

But Holloway was always the frontrunner, and everybody knew it.

During an intrasquad scrimmage, Holloway’s right hand was kicked while holding for an extra point try. Battle quipped, “That is a good way for a kicker to lose his job.”

In August, Fletcher had drifted out of the competition and decided to transfer to Iowa State, where he could play for Johnny Majors, the former Vols player and future coach.

Before he left, Fletcher said, “Condredge was obviously No. 1. And the other quarterbacks were just that – others.”

The only remaining contender was Gary Valbuena, a junior college transfer who arrived from California that summer with plenty of confidence.

“I’ve never been second string in my life,” Valbuena told the News Sentinel in June 1972. “I’ve been throwing some to my brothers (who were college athletes). I’m serious about football.”

In August, Battle said he might platoon Holloway and Valbuena with their own set of backs. But a week later, Valbuena and McDougal were battling for the No. 2 spot, and the competition was officially over.

And Holloway, now the starting quarterback, had already taken on new challenges.

Two weeks before the Georgia Tech game, Holloway made 14 of 15 extra points in a kicking competition alongside Clabo – the same player who upstaged him on signing day 19 months earlier.

Vols legend provided friendly confines for Holloway's debut

Holloway faced racist heckling at different stadiums during his career. A national TV game against Ole Miss in Jackson in 1973 was particularly vicious, according to his teammates.

But the start of his Tennessee career was well timed.

Georgia Tech, which left the SEC in 1964, already had a Black quarterback, Eddie McAshan. And athletics director Bobby Dodd made sure the environment welcomed his alma mater.

“We got exposed to fans heckling us from the stands at some venues, but not Georgia Tech,” Stanback said. “Bobby Dodd was too classy of a guy to let that happen.”

Dodd played quarterback for the Vols from 1928-30, as well as baseball and basketball.

In 1955, Dodd was the coach and athletics director at Georgia Tech, then an SEC power. The Yellow Jackets earned a bid to the Sugar Bowl to play Pittsburgh, which had one Black player on its roster.

Dodd agreed to play against an integrated team, which was scandalous in the South in the 1950s. He held his ground through protests and pressure from the Georgia governor to back out of the contract, and Georgia Tech played the game.

Seventeen years later, Holloway and McAshan staged the first major college football game in the South to feature Black quarterbacks on both teams. They played in a venue which would be renamed Bobby Dodd Stadium in 1988.

The Vols entered the game as a 6½-point favorite. Holloway led them to a 34-3 win.

“It was a smooth transition,” Brown said. “There are always a few idiots when it comes to race. But as good as Condredge was, he made them all happy that he was playing for our team.”

Twitter: @AdamSparks | Email | Support the best coverage of University of Tennessee athletics and enjoy subscriber perks. Visit knoxnews.com/subscribe.

Reach Adam Sparks at adam.sparks@knoxnews.com and on Twitter @AdamSparks.

This article originally appeared on Knoxville News Sentinel: How Tennessee football's Condredge Holloway became first Black SEC QB