50 years after his death, what J.R.R. Tolkien did for Christianity

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

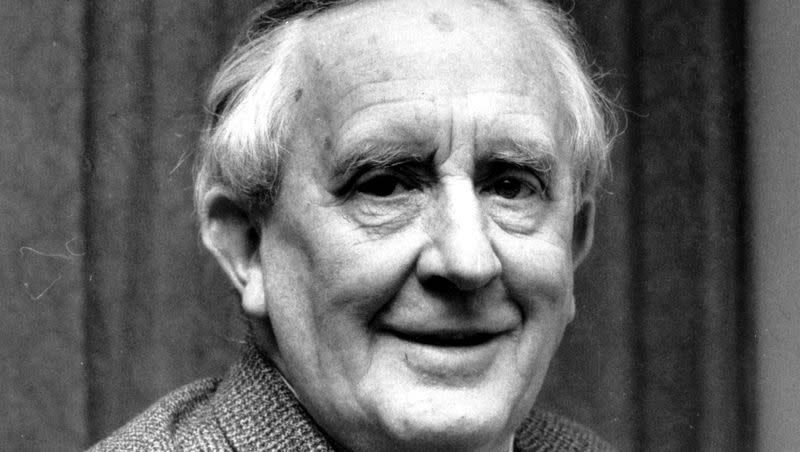

Hobbits, elves and Middle-earthlings across the globe will mark the 50th anniversary of J.R.R. Tolkien’s death this weekend. The English scholar and author best known for the worlds he created in “The Lord of the Rings” and other books died of pneumonia on Sept. 2, 1973, at age 81.

Tolkien had a remarkable career, one which continues to touch lives, not only in his literature, but through the relationships he fostered, including one with his fellow Oxford don C.S. Lewis. Last year, an article in the lifestyle magazine Town & Country said “It is impossible to overstate how much Lewis and Tolkien’s friendship impacted the shape of fantasy literature.”

Likewise, it is impossible to overstate how much that friendship impacted Christianity in the 20th century.

Lewis, of course, was a prolific writer whose nonfiction and fiction works were testaments of his faith. “The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe,” a powerful Christian allegory, remains a beloved children’s book, and “Mere Christianity,” as historian George Marsden has written, “has a claim to being one of the most important religious works of the 20th century.”

Tolkien wasn’t the only influence in Lewis’ journey from atheism to belief; Lewis was a fan of G.K. Chesterton and admired his book “The Everlasting Man,” and had read and appreciated the work of the Scottish minister and author George MacDonald.

But to borrow a line from the “Hamilton!” musical, Tolkien was in the room where it happened, when Lewis came to faith. Or to be more specific — on the wooded pathway where it happened, since it was during a famous late night walk at Magdalen College, with Tolkien and another friend, Hugo Dysen, that most of the remaining barriers to faith were broken down.

Related

Later, Lewis would write to Tolkien, “All my philosophy of history hangs upon a sentence of your own, ‘Deeds were done which were not wholly in vain.’” (It was a quote from “The Fellowship of the Ring” that Lewis mentioned when he reviewed Tolkien’s book.)

Unlike the friend he mentored in faith, Tolkien was a Christian for most of his life. After his father died, his mother joined the Roman Catholic Church, and Tolkien, then 8 years old, was received into the church. Four years later, his mother died of diabetes, and he and his brother were put under the guardianship of a priest their mother had selected.

Although scholars have long debated the religious symbolism of Tolkien’s work, he once wrote to a friend that “The Lord of the Rings” is “a fundamentally religious” work even though he famously shunned allegory and said his intent in writing the series was “to write a great story.”

That hasn’t stopped fans from combing through his books looking for Christian stories and symbolism. As Joseph Pearce, author of “Tolkien: Man and Myth,” wrote recently in the National Catholic Register, “‘The Hobbit’ can be seen as a parable and a meditation on Christ’s words that where our treasure is, there our heart will be also. Those who store up treasure on Earth become possessed by their possessions, succumbing to the ‘dragon sickness’ that devours all virtue.”

I never get tired of reading this passage. #LOTR #JRRTolkien #Thefellowshipofthering pic.twitter.com/mGVCdQv4EN

— Tri Perez (@SunflowerBookQT) August 28, 2023

In Tolkien’s obituary, The New York Times described “The Lord of The Rings” as “a fantasy of the war between ultimate good and ultimate evil.”

Throughout his life, Tolkien was a regular churchgoer, at one point attending services daily at 7:30 a.m., accompanied by his children. Humphrey Carpenter, Tolkien’s biographer, said faith was “one of the deepest and strongest elements in his personality.”

Just went to Mass at the same church where JRR Tolkien went to Mass 😭 #oxonmoot pic.twitter.com/7D6mksrxEQ

— Erin B (@erin_smc) August 31, 2023

In the letter in which he described the religious nature of his most famous work, Tolkien wrote: “The Lord of the Rings is of course a fundamentally religious and Catholic work; unconsciously so at first, but consciously in the revision. That is why I have not put in, or have cut out, practically all references to anything like ‘religion,’ to cults or practices, in the imaginary world. For the religious element is absorbed into the story and the symbolism.”

While he will not be remembered as an apologist this weekend, and not much has come of a push to canonize the author as a Catholic saint, Tolkien’s cultural influence remains strong worldwide — in both his own books and those written by Lewis. And for those who know Tolkien’s life story, it is impossible to separate his faith from his work.

For like a shaft, clear and cold, the thought pierced him that in the end the Shadow was only a small and passing thing: there was light and high beauty forever beyond its reach. #Tolkien#Beauty#Hope

— J.R.R. Tolkien (@JRRTolkien) August 18, 2023