50 years later, the murder of this 12-year-old boy weighs heavy on the Chicano community

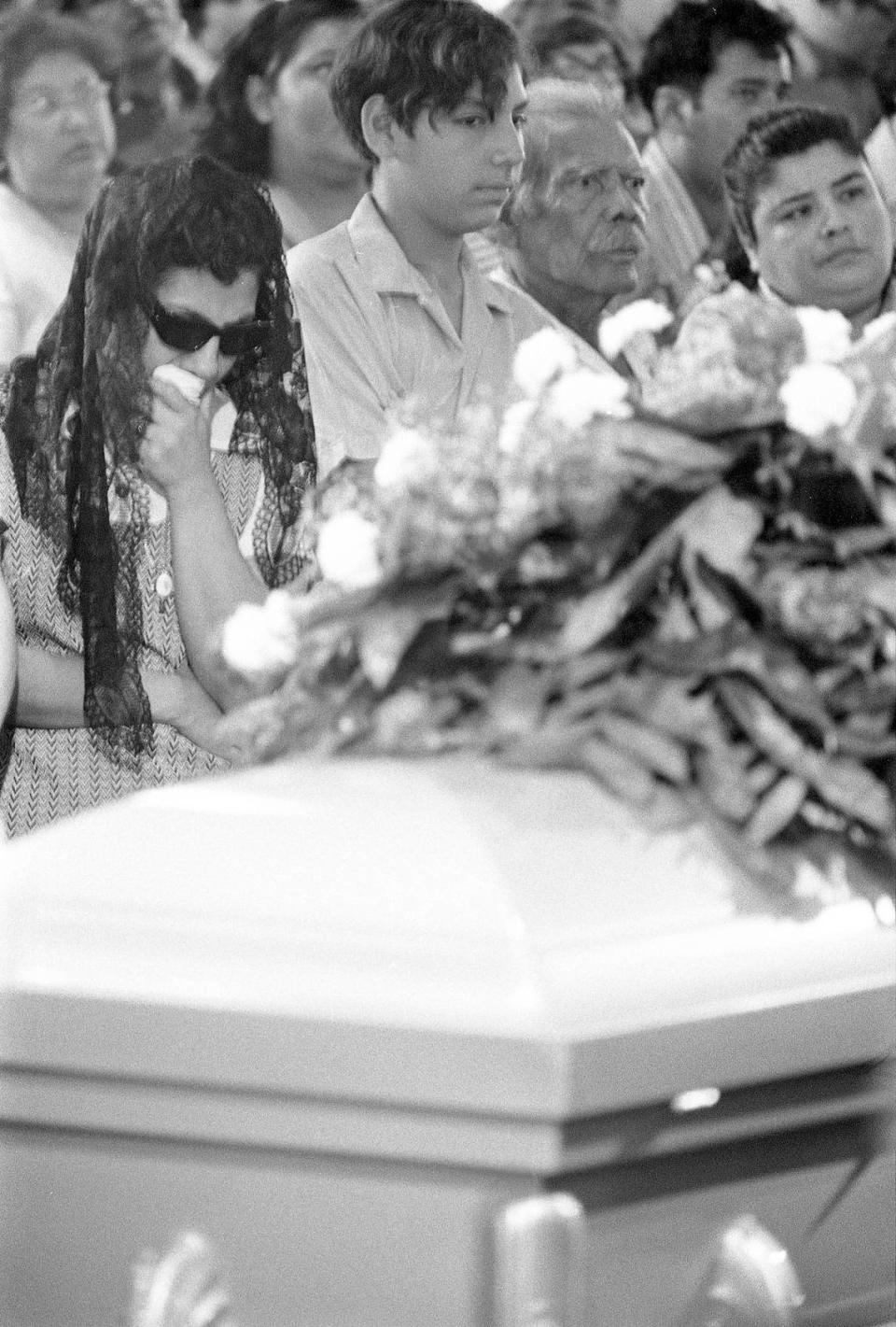

On July 24, 1973, Dallas police officers Darrell Lee Cain and Roy R. Arnold arrested 12-year-old Santos and 13-year-old David Rodriguez at their home. The police told the brothers’ 84-year-old guardian, Carlos Minez, who barely spoke English, they needed to question the boys about a burglary. The police handcuffed David and Santos, placed them in Arnold’s police car and drove to the Fina gas station, which they allegedly burglarized and stole $8 from a soda machine.

According to news coverage, Arnold drove with Santos in the front passenger seat while Cain sat in the back with David. Cain aimed his .357 Magnum revolver at Santos’ head and warned him to tell him the truth about the burglary. After pulling the trigger once, playing Russian roulette, Cain again warned Santos. The boy’s last words were, “I am telling the truth.” On the second pull of the trigger, Cain shot Santos in the back of the head.

Cain’s primary defense was that he thought he had emptied all the bullets from the gun. Dallas police officer Jerry Foster, who was standing outside of Arnold’s patrol car at the time of the shooting, examined Cain’s gun and found it fully loaded except for one empty chamber. Cain testified he reloaded the gun immediately after the shooting.

The murder of Santos unleashed the anger of the Dallas Chicano community. Rene Martinez, Pancho Medrano, the Rev. Rudy Sanchez, Brown Berets, and others demanded justice. They met with Dallas Police Chief Frank Dyson and the Dallas city council, demanding swift judicial action and police reform.

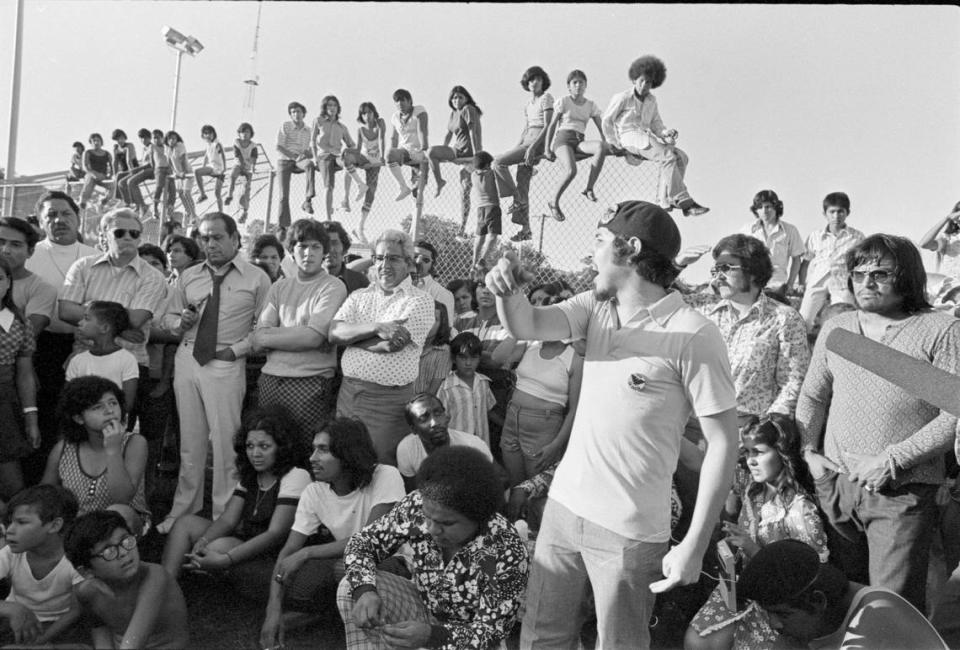

I was stationed at Fort Hood (now Fort Cavazos) in Killeen when I heard the news of the killing. That weekend I drove to Dallas to participate in the “March of Justice for Santos Rodriguez” on July 28, 1973. My voice joined hundreds of Latino and Black protesters’ howls, expressing our anger at the murder. The chanting crowd, carrying signs, marched from Kennedy Plaza to Dallas City Hall, then located at 106 S. Harwood. Several local Chicano leaders spoke to the gathering, which grew to more than 1,000, about injustice and need for community unity.

After the march and rally, some protesters broke store windows, set fire to a police motorcycle, damaged police vehicles, and injured five officers. Police dispersed the rioters, arresting 30 people.

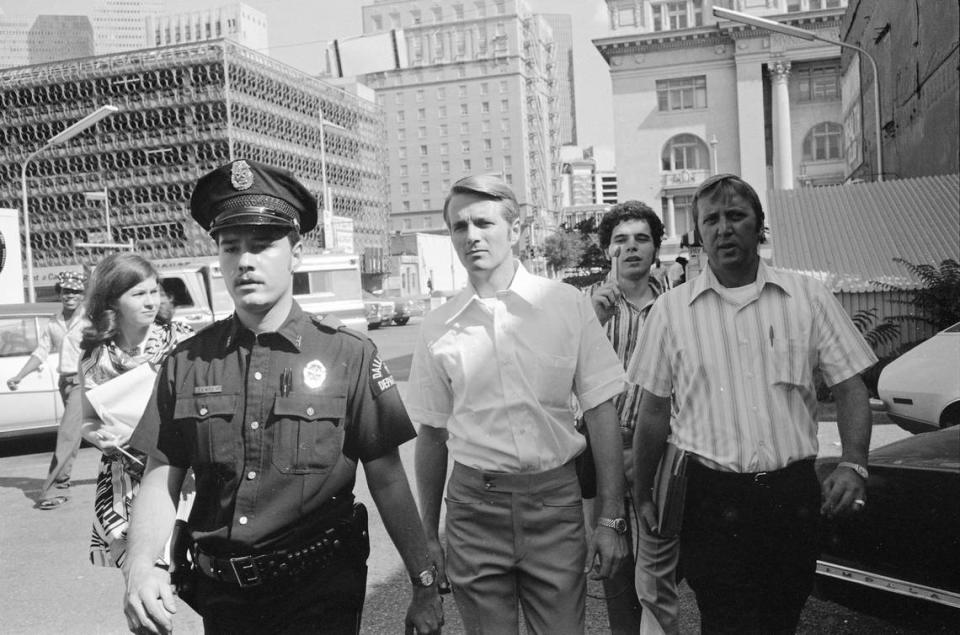

The venue for Cain’s trial was moved to Austin, where an all-white jury of seven men and five women deliberated on the case. Dallas Assistant District Attorney Doug Mulder argued that Cain had recklessly murdered Santos and deserved to go to prison. Defense attorneys Phil Burleson and Michael P. Gibson countered that Cain had shot accidentally, thinking the gun was empty. Burleson warned if Cain were convicted, prison would be a death sentence. On Nov. 16, 1973, the jury found Cain guilty of murder with malice and sentenced him to five years in prison. Cain’s attorneys appealed the verdict to the United States Supreme Court, but the justices refused to hear the case.

Cain served two and a half years in Texas State Penitentiary at Huntsville, acting as a trusty. According to the director of the Texas Department of Corrections, Cain behaved as a model prisoner, which earned him an early release.

In 1978, LULAC, Texas Latino legislators, and other civil rights organizations appealed to President Jimmy Carter for his assistance to file federal charges. Carter gave assurances that the Department of Justice would seriously review the case. Attorney General Griffin Bell declined to pursue additional charges, citing the length of time since the crime.

Santos’ mother, Bessie Rodriguez, wrote to Carter asking if his daughter had been murdered, would the killer have received a light sentence. She also wrote that if Santos had killed a police officer, his sentence would not have been as light as that given to Cain.

The city of Dallas worked to diversify its police department and to train officers to eliminate racist practices. On Sept. 21, 2013, Dallas Mayor Mike Rawlings apologized for this heinous crime. The first Latino Dallas chief of police, Eddie Garcia, hired in 2021, apologized to Bessie Rodriguez for her son’s death.

The city dedicated a statue to Santos at the Pike Park Recreation Center on Feb. 9, 2022. The center was renamed the Santos Rodriguez Center. Human Rights Dallas formed the “Santos Vive” project and helped release a documentary of the same name, highlighting the murder, trial, and community reaction.

Darrell Cain never worked again as a police officer and took a job as an insurance claims adjuster in Lubbock. Passing away in 2019 at the age of 75, his obituary partially read, “There was also a special place in his heart for his canine friends ...” No mention of Santos was made.

On the 50th anniversary of the murder of Santos Rodriguez, the Chicano community can’t forget his traumatic death. It still weighs heavy on our minds.

Author Richard J. Gonzales writes and speaks about Fort Worth, national and international Latino history.