50 years since Immaculate Reception: Erie connections part of memorable play's anniversary

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Editor's note: The Associated Press reported Franco Harris died two days before the 50th anniversary of the Immaculate Reception.

Go to the ball.

That was the football advice Pittsburgh Steelers running back Franco Harris remembered Joe Paterno, his college coach at Penn State, preaching even if a play call wasn't directly meant for him.

Go to the ball.

Harris vividly recalled those four words during his Oct. 12 appearance at Pittsburgh's Western Pennsylvania Sports Museum. It was there the four-time Super Bowl champion and Pro Football Hall of Fame inductee discussed 66 Circle Option.

More:Franco Harris, Steelers legend best known for making 'The Immaculate Reception,' dies at 72

From 2014: Steelers great Franco Harris helps 3 Erie charities

Or, as it's become better known since the late hours of Dec. 23, 1972, the Immaculate Reception.

It was 50 years ago this month that Harris, then a Steelers rookie, scored what's widely considered the greatest play in the National Football League's 103-year history.

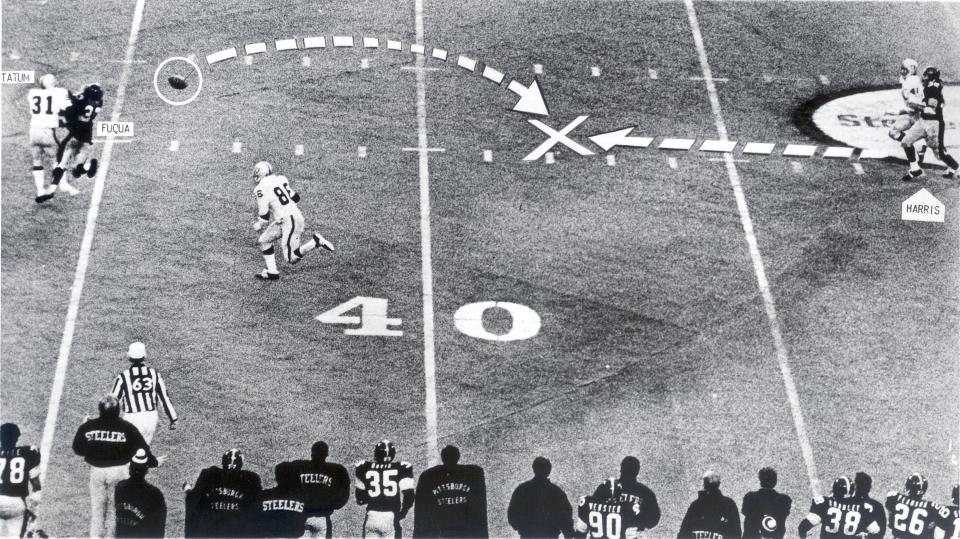

It began with 22 seconds left in the fourth quarter of the Steelers' AFC divisional playoff against the visiting Oakland Raiders at Three Rivers Stadium.

The Steelers, trailing 7-6, had to convert a first down on fourth-and-10 from their own 40-yard line. Coach Chuck Noll chose 66 Circle Option because it was one of the offense's few viable plays for such bleak circumstances.

What happened next was instant sports history.

Pittsburgh wide receiver Barry Pearson was Terry Bradshaw's designed target. Within seconds of the snap, though, the Steelers' quarterback found himself scrambling to his right as he eluded two Oakland pass rushers.

Bradshaw, unable to spot Pearson, attempted to connect with a running back he spotted near the Raiders' 35-yard line.

Not Harris, but John “Frenchy” Fuqua.

Jack Tatum, an Oakland safety and the team's most feared defender, also spotted Fuqua and the ball approaching him. The near-simultaneous collision caused the ball to sharply carom backwards for roughly five yards.

And toward Harris, who snagged the ricocheted pass several inches off the ground.

“When we were in the huddle (before the snap), I thought, 'Franco, play it to the end,'” Harris said. “On the play, I didn't have any assignment but to block. But then, when Bradshaw started to scramble, I thought to release and be an outlet (receiver). Maybe I'll still get the ball and get a first down.”

Harris accomplished each. And more.

The Steelers' first-round draft pick that year grabbed the deflected pass around the Raiders' 43. He scurried down the Steelers' sideline and, after a stiff-arm to Oakland cornerback Jimmy Warren around the 10, found himself in the Raiders' end zone.

“My mind was blank,” Harris said. “I remember nothing else after that.”

One extra point and 5 game seconds later, Pittsburgh had won, 13-7.

Pittsburgh's miraculous victory happened before a crowd of 50,327 that included three northwestern Pennsylvania residents.

Even closer to the play was Fred Biletnikoff. The 1961 Tech Memorial graduate, then an eighth-year receiver for the Raiders, was on their sideline while the Immaculate Reception unfolded.

The play was historic for other reasons. Harris' unlikely touchdown accounted for Pittsburgh's first postseason victory in the franchise's first 40 years of existence.

It also was the flash point for the incredible turnaround that followed.

Although the Steelers lost to the Miami Dolphins eight days later in the 1972 AFC Championship Game, they still would become the NFL's team of the 1970s by the decade's conclusion.

Harris was vital to the each of Pittsburgh's four Super Bowl titles between 1974 and 1979.

The New Jersey native, who was the league's second-leading career rusher when he retired after 13 seasons, was scheduled to receive his latest honor Saturday, the day after the Immaculate Reception's 50th anniversary. The Associated Press reported that Harris died two days before the anniversary of the iconic play.

Steelers legend dies:Franco Harris, Steelers legend best known for making 'The Immaculate Reception,' dies at 72

Pittsburgh will host the Raiders, now based in Las Vegas, on Christmas Eve. The 8:15 p.m. game, to be broadcast live on the NFL Network, will take place at Acrisure Stadium. The team's current home is located just west of where Three Rivers Stadium stood until 2001.

The Steelers will use the occasion to formally retire Harris' No. 32 jersey. He'll join former defensive lineman Ernie Stautner (70) and Joe Greene (75) with that rare honor.

'Keep going': From McDowell to Pitt to the NFL, James Conner heeds his own advice

Past or present northwestern Pennsylvania residents who attended the Immaculate Reception game recently talked with the Erie Times-News about their experiences from that day.

More: How much do you know about the Immaculate Reception?

Tom Wedzik

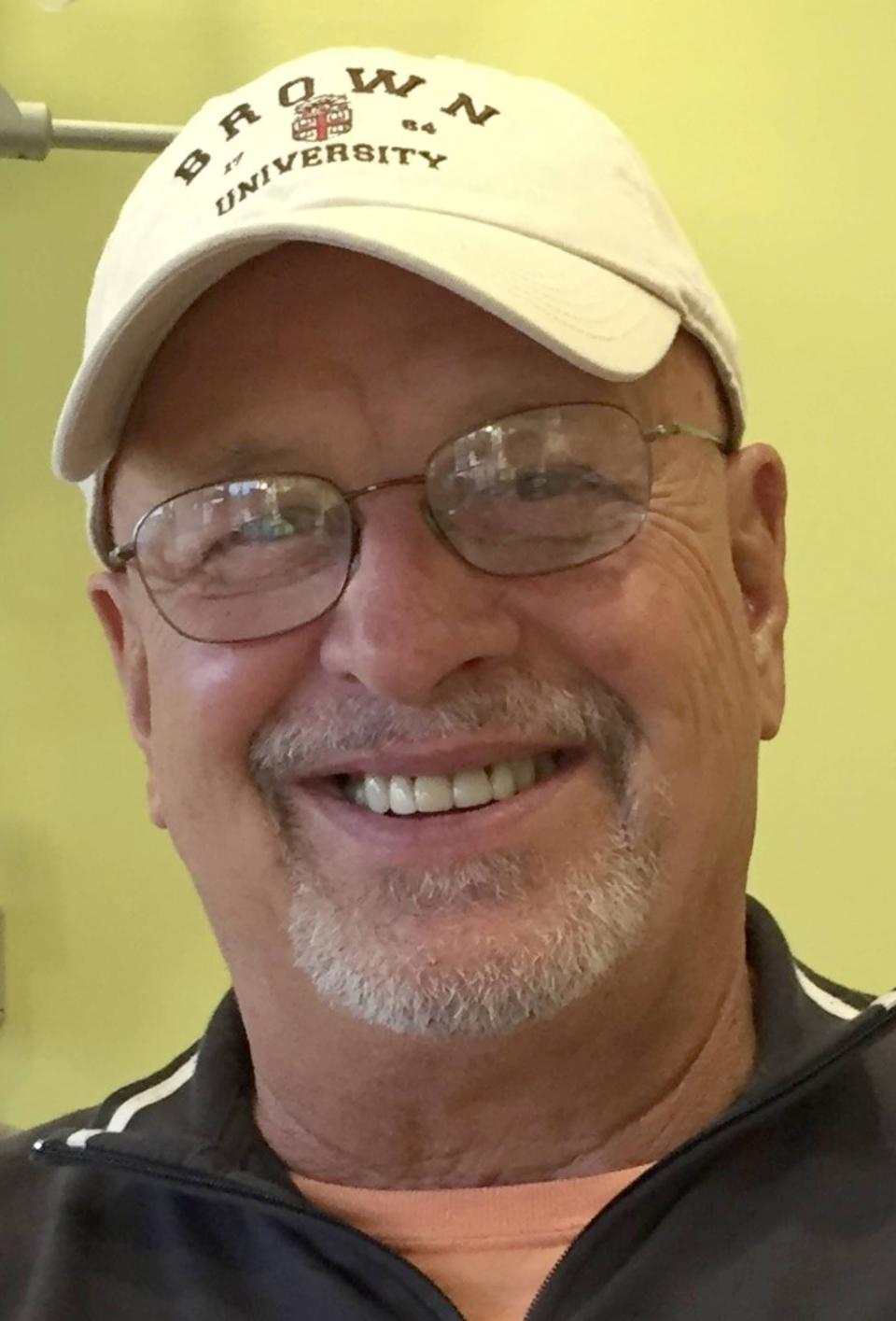

Although Wedzik, 77, now lives most of the year in Lakewood Ranch, Florida, he still spends summers in Erie.

No member of the three fans who spoke with the Times-News had a better vantage point of the Immaculate Reception than the 1963 Tech Memorial graduate.

“Our seats were on the (Steelers' side) of the 45-yard line,” he said. “We were about 15 rows up from the field.”

Wedzik worked for Security Peoples Bank, which owned four season tickets. He attended the game with his father, Al, as well as a fellow employee and his girlfriend.

Although definitely a Steelers' fan, Wedzik admitted there was conflict based on the team they faced that day. He was a sophomore at Tech when Biletnikoff was a senior there.

Wedzik also said that he and Biletnikoff, who caught three passes in the game, were technically coworkers on occasion.

“Fred worked for (Security Peoples) a couple of summers,” he said. “Those (NFL) guys didn't make any big money at the time, so he worked for us for three months before he went off to (training) camp.”

Wedzik, like many, assumed the Raiders would win going into Pittsburgh's fourth-and-long snap with 22 seconds left.

“Then, you see one of the greatest plays ever,” he said. “I swear, it felt like (Harris) caught that ball right in front of us. But we all still thought, 'Who knew what just happened?' because it happened so quickly.”

The collision between Tatum, Fuqua and ball remains the Immaculate Reception's greatest controversy to this day.

An NFL rule at the time stated only one offensive player was permitted to touch a thrown pass on any play. The league eliminated that rule in 1978.

Had Bradshaw's pass glanced off Fuqua first, whether Harris caught the ball or not would have been irrelevant.

Tatum, who died in 2010 at age 61, always claimed the ball struck Fuqua first.

Fuqua, now 75, has consistently declined to say if it did.

Instant replay from NBC's television cameras wasn't an option in 1972.

After what felt like forever to Wedzik and the crowd, referee Fred Swearingen finally ruled the play a legal catch with 5 seconds left.

“When the play happened live, obviously you didn't know,” Wedzik said. “I've watched that play a zillion times now … and I still don't know (if Tatum or Fuqua) touched it first.”

The Raiders, down 13-7 after Pittsburgh's Roy Gerela converted an extra-point kick, had no counter-miracle with the clock about to run out.

It's easy for newer and younger NFL fans to forget that while the Steelers won the game, it wasn't en route to the first of their league-tying six Super Bowl titles.

Miami's ensuing 21-17 victory over the Steelers in the AFC Championship Game was the Dolphins' 16th victory in their 17-0 season.

The 1972 Dolphins remain the only undefeated team in league history.

Nobody in the greater Pittsburgh area, though, had yet to worry about the next game in the jubilant chaos that followed the Immaculate Reception.

“People walked out of there still not believing what the hell just happened,” Wedzik said. “Everyone was chanting, 'It's destiny!' Well, why wouldn't you?”

Super Bowl 9: Steelers defense shuts down Vikings for first title

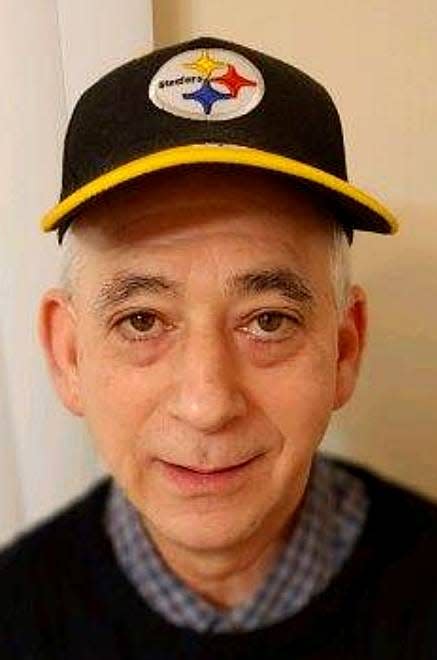

Barry Shapiro

The Immaculate Reception was an over-the-top bonus for Harvey Shapiro.

Just attending the Steelers' first-ever playoff game with his 10-year old son, Barry, would have been satisfying enough for the Youngsville resident.

“We had relatives (in Pittsburgh) on my father's side of the family who had season tickets,” Barry Shapiro said. “Dad called an uncle to see if he could warrant two extra tickets.”

The networking paid off, as father and son found themselves seated behind the end zone opposite where Harris scored.

Technically, those seats provided an unobstructed view of the action. In reality, though, Barry Shapiro had to peer over the backs and shoulders of the much older, taller fans who surrounded him.

Barry Shapiro said he had enough gawking with 22 seconds left and the Steelers down by a point.

“I pushed my seat down and climbed on top of it,” he said. “I only saw the tail end of (the Immaculate Reception) and when the Steelers were running on the field and mobbing Franco. I turned to my dad and said, 'I think Franco just scored and the Steelers are ahead.'”

Shapiro considers himself beyond fortunate that he experienced the play in person.

His luck was augmented by the fact Pittsburgh residents were prohibited from watching the game live at all.

The Immaculate Reception was a major reason the NFL rescinded its requirement that home games in a team's market be blacked out on television. That was implemented to promote ticket sales.

Now, a team's home games are permitted to be shown in its direct market if a game sells out 72 hours ahead of its scheduled kickoff.

Shapiro and his father stayed at his grandmother's Pittsburgh residence that entire weekend. They watched a replay of the game the next day.

By then, Harris' touchdown was already well on its way to being called what it's now known, courtesy of Myron Cope. The Steelers' color analyst doubled as a Pittsburgh TV sports reporter.

“Myron was all over the (Immaculate Reception) hype,” Shapiro said. “It was already starting the next day.”

Harvey Shapiro, who died in 2018 at age 86, gained some additional fame several years later.

Shapiro, who taught for 35 years in the Warren County School District, also served as a coach for Youngsville's track and field program. Among the student he worked with was Mike Shine, a star runner for the Eagles in the early 1970s.

Shine, who later competed for Penn State, was the men's 400-meter hurdles silver medalist during the 1976 Summer Olympics at Montreal. He finished second to fellow American Edwin Moses, whose time of 47.63 seconds set the then-world record.

Barry Shapiro, now 60, works for A Bridge to Independence. The service agency, a partner with Pennsylvania Health & Wellness, helps individuals with disabilities establish better methods for independent living.

As for the Immaculate Reception, Shapiro is more grateful now for witnessing it than he was in the wake of when it happened.

The Gannon University graduate suspects he's not the only one.

“I'm wasn't surprised at the impact (of it) after the circumstances of the play,” Shapiro said. “But I don't think any us quite realized the magnitude of it that Saturday.”

Super Bowl 10: Steelers win 2nd straight in classic over Cowboys

Terry Snyder

Like Wedzik, Snyder attended Tech Memorial around the same time Biletnikoff did.

The Erie resident, a 1960 graduate, watched the school's most famous athlete compete for the Centaurs' football team before and after he and his fellow band members performed during halftime of their games.

The Immaculate Reception also wasn't the first notable NFL postseason experience for Snyder, now 80.

The United Methodist Church pastor said was on a business trip in Los Angeles over the second weekend of January 1967. He sought to see as many of its noted landmarks as possible before returning to western Pennsylvania.

Something called the AFL-NFL Championship Game, which pitted the Kansas City Chiefs and Green Bay Packers at the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum, provided Snyder an easy reason to go.

“The seats were like $12 (per person),” he said. “Yeah, they were that cheap.”

That day, Snyder watched the Vince Lombardi-coached Packers defeat the Chiefs, 35-10. The inaugural AFL-NFL Championship Game is known now as Super Bowl I.

However, Snyder still considered himself a casual football fan at best in the early 1970s.

His interest escalated during his pastoral tenure at Electric Heights United Methodist Church, located in the Allegheny County borough of Turtle Creek. By 1972, his entire congregation seemingly had bought into the Steelers as a secondary source of inspiration.

Among them were members of the Isenburg family, who had season tickets.

Peg Isenburg, the mother, backed out from attending the Steelers-Raiders playoff because she was ill. Her husband, Ike, asked Snyder if he'd like to go with their daughter, Marjorie.

“It was a busy time for me with the church and being Christmas,” Snyder said. “But, I figured what the heck? It would be an experience, right?”

Right.

Snyder said that, similar to the Shapiros, they were seated in the corner of the opposite end zone from where Harris scored. He can still vividly see the entire play, even if he didn't fully understand what happened during it.

“It was after the fact that I realized the game was won because of that,” Snyder said. “Seeing the Immaculate Reception unfold in person remains miraculous. Etched in my memory forever.

“I kind of feel privileged to be part of that era.”

An era that's never really ended for Snyder. His wife, Shirley, and children and grandchildren are all proud citizens of Steelers Nation.

Super Bowl 13: Bradshaw outduels Staubach as Steelers top Cowboys

Immaculate marks the spot

It was Dec. 22, 2012, the day before the Immaculate Reception's 40th anniversary, that the play finally received its most significant memorial.

Much of where Three Rivers Stadium stood is now Acricure Stadium's eastern parking lots.

However, thanks to Three Rivers' blueprints, combined with the fortuitous placement of a sidewalk, the exact spot where Harris caught the ball was determined. An Immaculate Reception Memorial, with a replica of Harris' left cleat, marks the exact spot where he began his dash into sports history.

Expect countless fans who attend Saturday's game between the Raiders and Steelers to mob the memorial's location on the southern sidewalk of West General Robinson Street.

All there to understandably mimic or remember the Immaculate Reception.

“There will never be another one,” Wedzik said.

Contact Mike Copper at mcopper@timesnews.com. Follow him on Twitter @ETNcopper.

This article originally appeared on Erie Times-News: Erie connections part of 50th anniversary of the Immaculate Reception