In 1972, Madison set the community care standard for severe mental illness. Why don't we use it more?

Colleen remembers the day in fragments: She was serving and bumping a volleyball with friends, then she was sitting in a friend's driveway, then her parents were beside her in the emergency room. When she asked for a cigarette, she was surprised to hear she'd just smoked two.

The clinical term for what she experienced — a psychotic episode — didn't truly describe what Colleen, 20 years old at the time, went through. It was a complete "dropping out of reality," she remembered, a series of jolting moments instead of linear time.

It was 1982, a time when people could smoke inside hospitals, when funds for community mental health support dried up under the Reagan Administration — one consequence of which was the cutting of tens of thousands of beds in state-funded mental hospitals — and when employers could still terminate a worker for a mental health diagnosis. (The Americans with Disabilities Act wouldn't be signed into law until 1990.)

When she was admitted to the hospital for six weeks, Colleen was neither given a diagnosis nor allowed to leave. She sat isolated in a room, her concerns ignored by staff, increasingly desperate. When she snuck past the front desk and out through the emergency door, security officers hauled her back.

"The trees were full of colored leaves when I got there, and empty of leaves by the time I left," Colleen said. "That was not a good experience."

Without the right care, Colleen faced the prospect of life on the streets, in jail, or back in a hospital.

But that didn't happen.

On her 21st birthday, a psychiatrist named Dr. William Knoedler showed up at her door with a cake. He had met her briefly in his clinic, diagnosed her with schizoaffective disorder bipolar-type, and understood the problems inherent in inpatient care for those with severe mental illness — one of which was following up with their doctor.

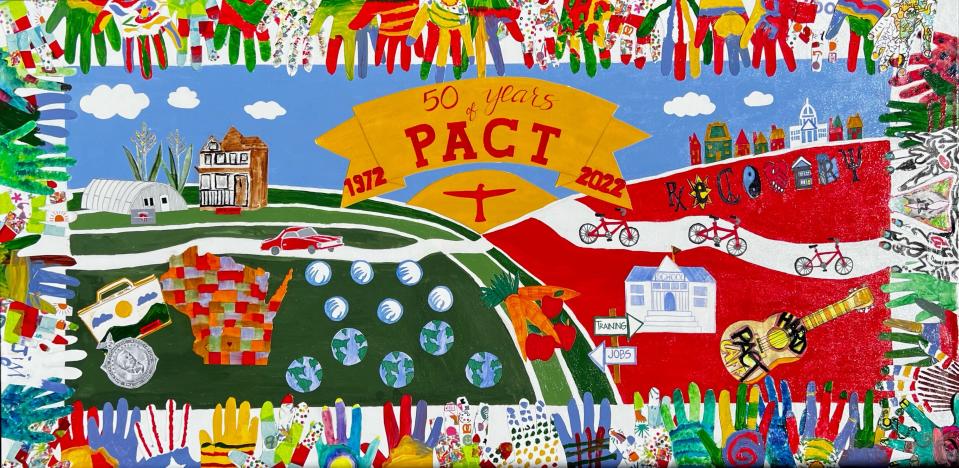

Knoedler was from the Program of Assertive Community Treatment, commonly referred to as PACT, a Dane County-based program that, since 1972, had changed the way doctors across the world treat people with severe mental illness.

Colleen's been a client of PACT ever since, but even today, stigma surrounding her mental illness prevents her from comfortably disclosing her last name. Her case manager at PACT, Christine Ahrens, joined the program in 1996 and has worked with Colleen since then. Ahrens has helped her maintain employment, manage her illness and talk through family relationships.

"We've known each other for so long, and because we see each other often, it doesn't take long to figure out whatever the issue is," said Ahrens, who also is a psychologist at PACT.

Since being in PACT, Colleen has thrived. At 62, she lives by a lake, drives a BMW, has a good job and, through hard work, has been able to raise two healthy kids with her husband, who has traveled beside her on their journey to a good life.

"A huge thing for people to know is that having a job and living someplace among people makes a huge difference in your life," Colleen said. "I could have been living in some (expletive) little apartment with no more money to my name had I not gone back to work and decided to go on disability. But look where I am today."

14 million adults with severe mental illnesses lack support systems

Just 65% of U.S. adults with a serious mental illness received mental health treatment in 2021, according to the nonprofit National Alliance on Mental Illness, and that percentage is closer to 60% for those with mental illness between ages 18 and 25.

That means at least 35% of people with severe mental illnesses, about 5 million, are on the street, or stuck in jails, or white-knuckling their symptoms. The rate of mental disorders in the incarcerated population is 3 to 12 times higher than that of the general community, according to Weill Cornell Medicine.

The future, even of those who do receive care from a psychiatric hospital or clinic, depends on quality comprehensive care. Most of the estimated 14.1 million U.S. adults living with severe mental illnesses don't have support systems in place that allow them to live independently.

When fully funded and implemented, community treatment programs work, evidence shows. But only a fraction of the people with severe mental illness enjoy the benefits of the kind of assertive community treatment program Colleen relies on.

PACT stands apart from most community treatment programs. In the late 1960s, an inpatient research unit at Mendota Mental Health Institute (formerly called Mendota State Hospital) conducted an experiment, keeping patients in their community while supporting them with comprehensive mental health services. The study found that the back-and-forth cycle of hospitalization for those patients could be broken, and they could make real progress. It ultimately won an American Psychological Association Gold Award.

"The genius (of the study) was to move the unit to where the people live and work, and teach them in vivo (meaning real life scenarios), in a very applied fashion, the skills that are needed to live independently and successfully," said Jana Frey, director of PACT.

The study out of Madison popularized a novel concept: a team of professionals could deliver services to people with severe mental illness in the real world 24 hours a day, seven days a week.

PACT, known colloquially as the "Madison Model," has been adapted across Wisconsin, in 41 states and 10 countries.

By 1989, based on the success of PACT, the Department of Human Services promoted the widespread use of community support programs, considered an adapted PACT model. State Medicaid plans incorporated community support programs soon after.

Still, programs as robust and rigorous as PACT are rare across Wisconsin, even though Wisconsin statute chapter 51 obliges counties and tribes to make similar community support programs available and easily accessible.

In place of adequate support systems to give patients a chance at housing, a family, a hobby, a passion and a purpose, most comprehensive mental health programs modeled after PACT are hobbled by staffing shortages and an inadequate reimbursement system, and can't accommodate everyone.

Community support programs drew renewed attention when Gov. Tony Evers signed the biennial budget in July. Declaring 2023 "The Year of Mental Health," Evers proposed $500 million in mental health funding, which included putting $40 million into community support programs. But very little of the final $99 billion budget — including any funding for community support programs — ultimately went to mental health programming.

That rejection of funds was a major disappointment for both mental health advocates and staff at many community support programs across the state, who hoped the government was ready to take more action supporting Wisconsinites with severe mental illness. And $40 million over the biennium would have been "peanuts" compared to the more than $1,300 per day cost of each person admitted to a state hospital, said Michael Lappen, administrator of behavioral health services for Milwaukee County, a division of Health and Human Services.

"I'm holding out hope (for future funding) because it's one of those things people just don't understand," said Lappen, who is also one of the tri-chairs of the Wisconsin County Human Services Association's Behavioral Health Policy Advisory Committee. Community support programs have "tremendous value in actually reducing costs, but more importantly, this is a program that really improves people's lives and their outcomes."

Every client is provided a continuum of care

Lappen knows first-hand how effective community support programs can be. One of Lappen's family members has schizophrenia, but before it was diagnosed, the people in his life thought it was the persistent effects of hard drugs.

It took many years for Lappen's family member to realize the extent of his illness, which pushed him to get help from Milwaukee's community support program. He received psychoeducation about schizophrenia, started taking medication and, through the community support program team, learned to live independently. He eventually earned a master's degree and a lucrative job.

"He is one of the positive stories because he came to understand his illness and, of course, I was in his ear quite a bit about how he could recover," Lappen said.

A majority of community support program clients have schizophrenia, a disease that gets progressively worse if it's not treated, said Russell Marmor, clinical coordinator of the community support program in Outagamie County's mental health division. It's especially tricky because of the other problematic characteristic of schizophrenia: most people with it don't think they have it, due to a common neurological symptom of the disease known as anosognosia.

"In order to effectively treat someone with schizophrenia, you have to identify it early, and then build a relationship," Marmor said. "And then you need to get this individual into a niche in the community, where they have their needs met. Hospitalization doesn't even scratch the surface of what these folks need in order to have a decent quality of life."

The beauty of the programs, according to community support program coordinators around the state, is that clients are provided a continuum of care, usually a team of specialists from case managers to vocational counselors to psychiatrists. They can help clients with all aspects of independent living, whether that means monitoring their medications, working with them on job applications or transporting them to doctors' appointments and the grocery store.

"Sometimes people think, 'Well, why are you taking somebody shopping?' We're helping them build skills that most people might take for granted," said Luke Fedie, behavioral health administrator for Eau Claire County's Department of Health Services, which includes services like the community support program. "When you have someone who has struggled with psychosis most of their life, just going to the grocery store can be a huge barrier. Being able to provide assistance for such an individual is huge."

For Gratus Jamerson, 63, a resident of Onalaska in La Crosse County, mental illness is compounded by chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and past incarceration.

He's retired from his job as a cook at KFC, collects Social Security and lives in an income-based apartment. Money is a constant struggle, but when he can, he enjoys going to thrift stores in search of the perfect cuckoo clock. He likes the idea of owning one, winding it up, hearing it tick.

When USA TODAY NETWORK-Wisconsin spoke with them, Jamerson and his community support program case manager, Samantha Buedding, had recently returned from meeting Jamerson's new long-term care worker, where she explained Jamerson's at-home needs.

Without La Crosse's community support program, Jamerson, who doesn't have a family, would be completely isolated and besieged by his disabilities and the many financial burdens that come with them. So many people with severe mental illnesses get forgotten by their communities and families, Buedding said.

"People get lost and they need guidance throughout their lives," Buedding said. "We're the middlemen who get them where they need to go, get the treatment they need, the food they need to survive, the housing they need to not be homeless."

Mental illnesses can sever family ties, whether due to the weight of the illness on family members, families shunning the notion of mental illness, or the extreme behaviors that come with psychotic episodes.

"For the first time in my life, people really care about my life," Jamerson said. "They help me go in the best direction, instead of my own direction, which isn't always good for me."

In the 50 years since Madison disseminated its assertive community treatment program across the world, Frey said, it's been adjusted in one community after another, often because of cost. The result, Frey said, is that the success rate isn't what it could be.

Frey said the standards that make PACT successfully dictate everything from psychiatric time to client-to-staff ratios. Most community support programs across the state can't meet PACT's standards of care.

The average delay between the onset of mental illness symptoms and treatment is 11 years, in large part because of the lack of availability of treatment options.

"There's so much need out there. If funding looked different for us, it would give us the opportunity to open the doors differently for people," said Christin Skolnik, integrated support and recovery services manager for La Crosse County Human Services. "I'm trying always to advocate why community support programs are so important, why fully funding them is so important."

Colleen has numerous examples of above-and-beyond care

Today, Colleen is doing well. That's not something she would have envisioned for herself back before Knoedler visited her home. Through her struggles, however, she had a strong support system in her friends, her boyfriend, her college roommates and her parents, which dovetailed into strong support from her team at PACT.

There was the time Colleen was struggling to adjust to her new prescription dosage and a case worker, sensing her need for a break, brought her and her two young kids at the time to the Shedd Aquarium in Chicago. There was the time Colleen was so anxious and freaked out that someone from PACT showed up at her door to talk with her in the middle of the night.

And there was the time when, 10 years ago, she decided to step away from PACT, believing herself comfortable on minimal medications, and had another psychotic episode. PACT was there to give her husband all the tools he needed to support her — and then welcomed her back.

"Colleen called me and said, 'Christine, something terrible happened to me. I'm back in the hospital. Would PACT have me back as a client?'" Ahrens remembered. "And I said, 'Of course we will.'"

For Colleen's nephew, treatment options were out of reach. When he expressed concerns to his family, they brushed him off. Colleen understood him, but she was had her own struggles to focus on. He was "living on shoestrings" as he struggled to maintain a job and the world got too intense. He chose to end his life.

"That was the huge difference between us. I had a network of support and he didn't," Colleen said. "It's an example of me being in PACT and people that are not in PACT."

Devi Shastri of the Journal Sentinel staff contributed to this report.

Natalie Eilbert covers mental health issues for USA TODAY NETWORK-Wisconsin. She welcomes story tips and feedback. You can reach her at neilbert@gannett.com or view her Twitter profile at @natalie_eilbert. If you or someone you know is dealing with suicidal thoughts, call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 988 or text "Hopeline" to the National Crisis Text Line at 741-741.

This article originally appeared on Green Bay Press-Gazette: Madison trailblazed severe mental health care with PACT in 1972