At 6 mph, a ride on Pittsburgh’s historic incline shows what Cincinnati used to have

Ever since I first read about Cincinnati’s inclines, I wished I could ride one.

The city once had five inclined plane railways – inclines for short – twin tracks that carried streetcars up and down Cincinnati’s hills. These were a major development for the city in the 1870s, when horse-drawn carriages struggled to carry people en masse up the hills. The inclines allowed Cincinnatians to climb out of the downtown basin and establish the suburbs, such as Price Hill, Clifton and Hyde Park.

But the last of Cincinnati’s inclines, the Mount Adams Incline, closed in 1948. I’m 75 years too late.

Lo and behold, Pittsburgh managed to retain two of its inclines. So, on a trip over Thanksgiving week, my family and I made a stop in the Steel City to finally ride an incline and see what Cincinnatians experienced a century ago.

Pittsburgh’s inclines provided the example

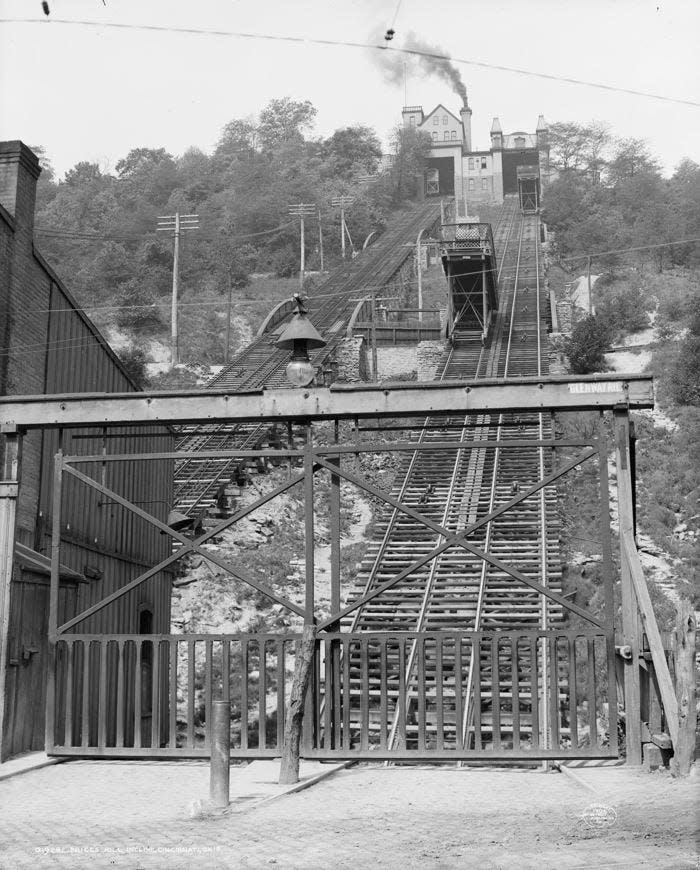

Cincinnati borrowed the idea of the inclines from Pittsburgh, which used them as a solution to ascending its Mount Washington (then called Coal Hill), a residential neighborhood atop a steep hill that was a respite from the smoke and soot belched out by the industrial city. But around the time of the Civil War, the only way up the hill was a muddy, zigzagging trail.

In 1854, Pennsylvania approved the creation of the Mount Washington Inclined Plane Co., authorizing the construction of several inclines to access the hill.

The Monongahela Incline was the first built, designed by civil engineer John J. Endres, with cables provided by John A. Roebling (the builder of our famous bridge). It opened May 28, 1870, costing passengers 5 cents to ride.

The Duquesne Incline was built about a mile away, opening May 20, 1877. In total, Pittsburgh had 17 inclines operating in the late 19th century, some lasting until the 1960s. The Monongahela and Duquesne inclines are the only two of them still running, now more tourist attractions than commuter transportation.

Inclines helped Cincinnati climb its hills

Cincinnati used inclines to solve its own hill problem.

Having seen Pittsburgh’s example, Joseph Stacy Hill and George A. Smith partnered to construct an incline from the end of Main Street up to Mount Auburn. The Main Street Incline, also known as the Mount Auburn Incline, opened on May 12, 1872, with 6,000 passengers riding on the first day.

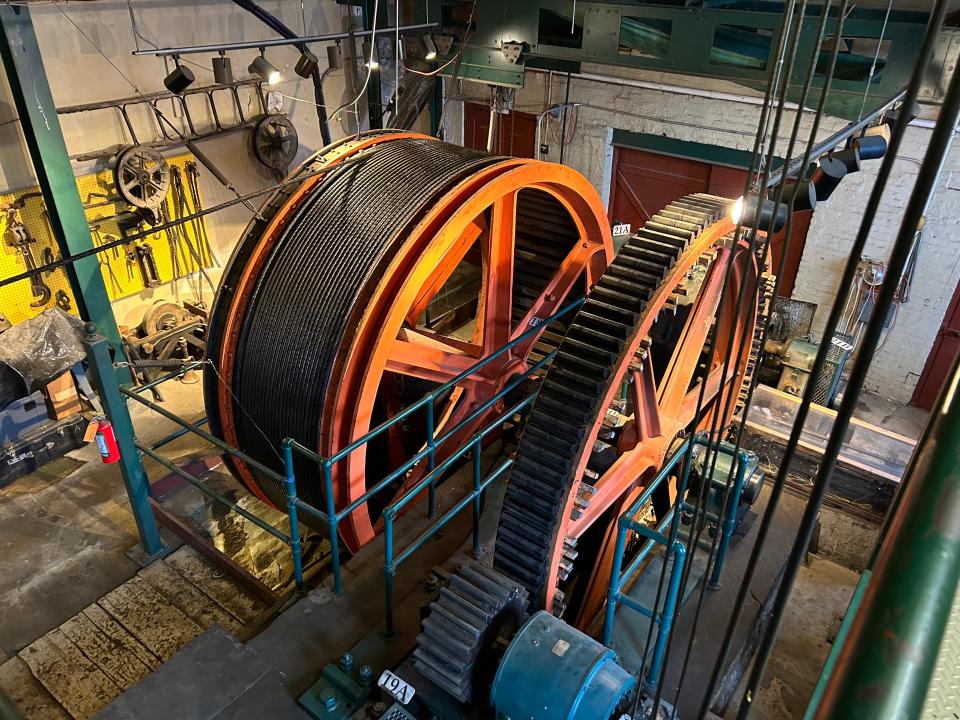

The incline was powered by two steam engines on the summit with large windlasses (cylinders turned by crank) that wound steel cables pulling cars up and down two parallel railroad tracks on the hillside. Like in a pulley system, one car went up while the other went down. The incline cars were built on stilts to remain parallel with the horizon.

This was a game changer for Cincinnati, giving the people breathing room.

The Enquirer wrote at the time: “The barbarians of the lower plane have at length sealed the rugged ascent to their fastnesses, and will soon be besieging their castle gates, clamoring for admission to the broad fields, the sunny slopes and the pure air of the upper plateau. And there they will build their homes, leaving the city with its crowded streets, its smoky, begrimed houses, its odors and its filth to commerce and manufacturers.”

Cincinnati had five inclines in all: Main Street Incline (1872-1898), Price Hill Incline (1875-1943), Mount Adams Incline (1876-1948), Elm Street Incline (1876-1926) and Fairview Incline (1894-1923).

All but the Price Hill Incline were owned and operated by the streetcar company, which tired of them long before the public did. Streetcars would roll onto a platform to ascend or descend the hill, which was time-consuming. Eventually, inclines became unnecessary when automobiles came around and people could drive up and down the hills on their own. So, whenever an incline went down for repairs, they were quietly closed instead.

But Pittsburgh's Duquesne Incline managed to survive its closure in 1962, in need of major repairs. Residents and preservationists worked to restore and rehabilitate the cars, stations and equipment, and the Duquesne Incline reopened in June 1963. It has been in operation ever since.

Our History: Tragic tale of the whales displayed at a Cincinnati resort in 1877

Riding the historic Duquesne Incline

Because Pittsburgh managed to hold onto a couple of its historic transports, I was finally able to experience a ride on an incline for myself.

On the morning before Thanksgiving, we found the Monongahela Incline was down for repairs, so we were able to ride only the Duquesne Incline (pronounced doo-kayn).

The Duquesne Incline was the first Pittsburgh incline designed by engineer Samuel Diescher, a Hungarian immigrant who had settled in Cincinnati and, according to the Price Hill Historical Society, designed and supervised the construction of the Price Hill Incline in 1875.

Diescher moved to Pittsburgh to build the Duquesne Incline, then went on to design the majority of inclines throughout the country.

Looking at the design, the Price Hill Incline was the most like Pittsburgh’s inclines. Instead of a platform for streetcars, as the other Cincinnati inclines had, there was a passenger car to carry folks.

The Duquesne Incline lower station at 1197 W. Carson St. is a turn-of-the-century red brick building. The lobby’s ticket booth is wood-paneled with beveled glass. We paid our fare, $2.50 each way, dropping the bills into a cash box. (They accept exact cash only.)

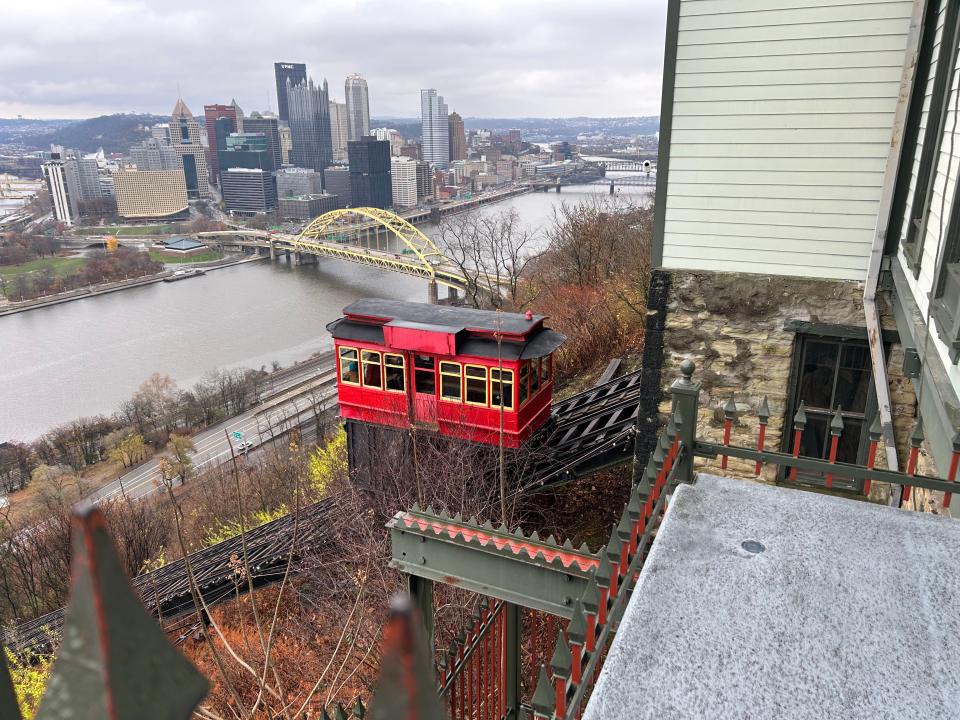

The incline car (still original) looks like a wooden trolley car, schoolhouse red with yellow window trim and a black roof. The interior has wooden benches along the sides and a pressed copper ceiling. But we were too busy looking out the windows.

Pittsburgh’s inclines have Cincinnati beat for the view. The incline looks out onto the city’s Golden Triangle, a wedge of downtown at the point where three rivers converge – the Ohio, the Allegheny and the Monongahela. The vista got better as we ascended.

The incline travels at a speed of 6 mph, up 794 feet of track at a 30-degree grade. As our car went up, we passed the other car coming down halfway. It is all very reminiscent of being inside a full-sized model train display. The ride lasted about 2 minutes, 30 seconds.

At the upper station at 1220 Grandview Ave., there is an observation deck (with postcard views), a museum and a gift shop. A man operates the controls from a closed-off room between the tracks. One wall is papered with photos of inclines from all over the world, both funiculars like this one and gondola skyways, and I spotted Cincinnati’s historic inclines among them.

Visitors also have access to see the incline’s hoisting equipment – a massive cable drum drive (it switched over from steam-powered to electric in the 1930s). Diagrams on the walls help to decipher how the mechanism works. It is impressive to see in action.

Time to head back down – wait for the green light that it is safe to board. We sat at the front window seat for the view. An alarm bell buzzed twice, and the car began slowly gliding down the track.

On the trip back down the incline, I felt like a traveler in a different time and fervently wished that Cincinnati had somehow managed to keep one of these as well.

Sources: Duquesne Incline (www.duquesneincline.org), Monongahela Incline (monongahelaincline.com), “Cincinnati, City of Seven Hills and Five Inclines” by John H. White Jr., pghbridges.com, Wikipedia, Price Hill Historical Society, Enquirer and Pittsburgh Press archives.

This article originally appeared on Cincinnati Enquirer: Pittsburgh’s historic incline is a 6 mph glimpse of Cincinnati history