A 6-story mound with a restaurant on top in downtown Fayetteville? What might have been

Imagine if downtown Fayetteville today had four lakes amid a vast park, a Black history museum, a performing arts center, an art museum, thousands of homes, and a six-story earthen structure with a 40-foot waterfall on the side and a restaurant on top.

In 1996, a committee called A Complete Fayetteville Once & For All proposed all of these ideas and much more to turn the city’s then-moribund downtown back into a thriving hub of commerce, life and entertainment.

Their report was called the Vision Plan. It may have been the most ambitious of various downtown revitalization proposals advanced over the last 50 years.

“I think the plan was a little bit ahead of the time, really. Quite a bit,” said Menno Pennink, who served on the committee. “We didn’t have enough traction and support.”

Little of the Vision Plan — commonly called “The Marvin Plan” because it was produced by consultant Robert E. Marvin — has been implemented. But downtown Fayetteville today by most accounts transformed for the better since 1996 and is continuing to rise.

“Robert Marvin was a tremendous visionary,” said John Malzone, who has been a longtime property owner and real estate agent downtown. “And what he did, was he got those people who never thought about downtown in the future to think about downtown as a point of future growth for the city.”

Marvin died in 2001, so he never saw what Fayetteville did with his plan. Here is a look at what the Marvin Plan proposed versus what has happened, and what people connected to the plan and downtown have to say about it.

Downtown in the early 1990s — strip clubs and empty stores

In the early 1990s, Fayetteville’s Minor League Baseball team was the Fayetteville Generals, and the games were played 4 miles away at J.P. Riddle Stadium on Legion Road instead of at a modern ballpark on Maiden Lane.

The big retail stores that used to draw people downtown had long since moved 5 miles away to Cross Creek Mall, which opened in the mid-1970s. Some stores and restaurants soldiered on, in between empty and boarded-up storefronts. And there were city and county government offices.

What was left to regularly draw people downtown? Topless bars, including the then-famous Rick’s Lounge, continued to operate on Hay Street.

Civic and city leaders wanted a change. They wanted a plan for the future.

Enter: Robert E. Marvin, landscape architect

In March 1994, the boosters met with Robert E. Marvin, a noted urban planner and landscape architect from South Carolina. Some of Marvin’s prior projects, according to a brief biography, include Harbor Town at Sea Pines Plantation on Hilton Head Island in South Carolina; the Henry C. Chambers Park in Beaufort, South Carolina; and the Governor’s Mansion and Finlay Park in Columbia, South Carolina.

In June 1994, the boosters brought Marvin to Fayetteville to show him the city and see what he thought. Marvin reviewed 27 plans that had been drawn up for downtown Fayetteville since 1975, The Fayetteville Observer reported.

He promised to build on those plans, with the goal of generating something that the city might actually do, instead of producing yet another book that would sit on a shelf next to all the previous plans.

April 1996: A new vision for Fayetteville

Nearly two years and $450,000 later, the Vision Plan — a.k.a. the Marvin Plan — was released with fanfare at the Cumberland County Civic Center before a crowd of 900 people, the Observer reported.

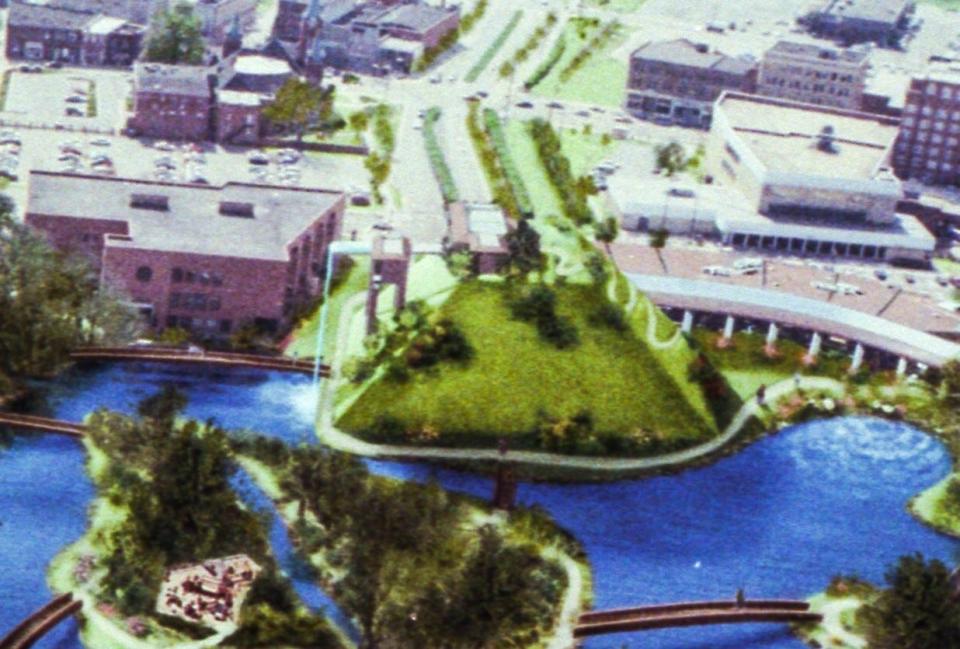

The vision was vast — with projects spanning 3,000 acres. They ran from a marina and housing on the Cape Fear River to the current core downtown area to the Martin Luther King Jr. Freeway to the Fayetteville State University campus.

It included a 45-acre park with four lakes, and another park area with ballfields and an indoor swimming pool. There would be an arts plaza and an art museum, and an amphitheater.

Residential areas would put homes in and around the downtown area.

Tree corridors would line Rowan and Grove streets, Person Street and Russell Street.

And the anchoring feature would be “the Mound.”

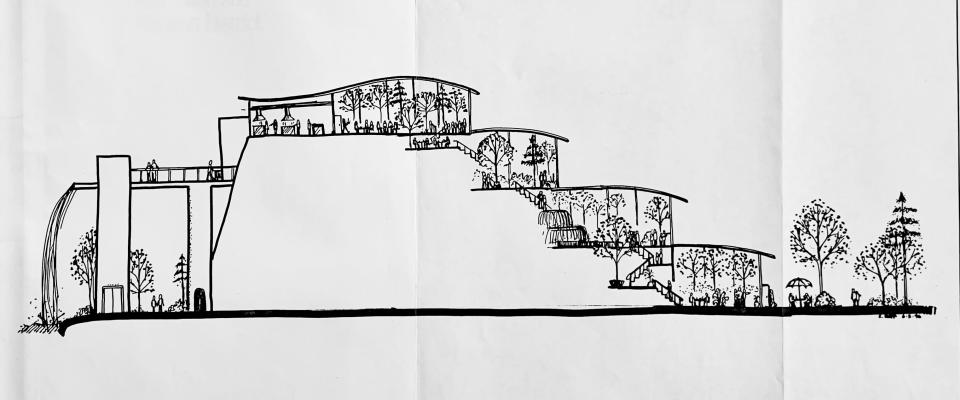

It would have been more than a pile of dirt. The Mound was supposed to become a world-famous landmark, situated on Ray Avenue across from the Cumberland County Headquarters Library, where the Festival Park Plaza building is now.

At 60 feet in height, the Mound’s amenities were to include a 40-foot waterfall, glass-enclosed gardens on terraces and the restaurant at its top.

It does not appear that a total cost estimate was published. The park, proposed to be the first phase of the redevelopment, was pegged at $28.7 million: $1 million for its amphitheater, $2.5 million for lakes, $2.6 million for an open-air pavilion, $4.4 million for a parking garage for 500 cars, and $8 million for the Mound.

To build the park as Marvin envisioned, the railroad tracks in that part of downtown needed to be moved. That added another $15 million to the park’s $27.7 million cost.

Downtown has had a slow-moving renaissance in the 27 years since. But for the most part, not according to the Marvin Plan.

Uptown glories

Perhaps the main artifacts that could be credited to the Marvin Plan are the Cross Creek Linear Park and the Cape Fear River Trail, Festival Park and the U.S. Army Airborne & Special Operations Museum.

The plan included bicycle and walking trails along the Cape Fear River. Now Fayetteville has Linear Park on Cross Creek in downtown Fayetteville and the Cape Fear River Trail.

The city never built the 45-acre park with lakes, amphitheater and 60-foot Mound, but Festival Park, the site of many popular events and concerts, is there now.

In 1996, when the Marvin Plan was released, no one had any idea the Airborne Museum was on the horizon for Fayetteville, said Mac Healy, who was chairman of A Complete Fayetteville Once & For All committee.

The Marvin plan had marked that corner of Hay Street at Bragg Boulevard for a “Special Hay Street Project.”

“An appropriate program should be developed for this key site, with special attention on the architecture,” the plan says. “The style of this area must reflect the revitalization of all of uptown Fayetteville if it is to fulfill its opportunity.”

The Marvin Plan described this part of Fayetteville as “uptown” instead of “downtown.”

Several years later, when the Army was scouting for a location for the museum, that location was picked for it. Now, the Airborne museum is a popular attraction.

“If there hadn’t been some interest in re-doing downtown, the military would have said, ‘We're not putting this valuable asset in the middle of a run-down downtown,’” Healy said. The Airborne museum would have gone elsewhere.

Later, downtown’s military-themed “campus” expanded with the North Carolina Veterans Park next door to the Airborne museum and Freedom Memorial Park across the street on Bragg Boulevard.

Other developments emerged over time, including Segra baseball stadium with the Fayetteville Woodpeckers. The city also opened the Fayetteville History Museum on Franklin Street.

Soon the Crown Event Center, a new performing arts space, will be built on Gillespie Street by the Cumberland County Courthouse.

As for housing, the downtown area hasn’t seen thousands of new homes, but the Prince Charles Hotel is now an apartment building, the 300 block has high-end condos and townhomes, and more condominiums have been built at the base of Haymount Hill. The former Grove View Terrace housing project on Grove Street was razed and replaced with an affordable housing complex called Cross Creek Pointe.

The Marvin Plan wasn’t the last Fayetteville downtown redevelopment plan. In 2002, the city commissioned an update called the Renaissance Plan. A year later, a 400-foot kaleidoscope tower was proposed to be built as a landmark for the then-upcoming Festival Park. The tower was never built.

Then the 2002 Renaissance Plan was updated in 2013.

But the dream-filled Marvin Plan may stand out most in the memories of longtime Fayetteville residents, even though in the end it was largely left behind.

“The community, and those that wanted to, immediately attacked the Mound. And the Mound never really took hold,” Healy said. Marvin’s thinking was the Mound would be built with the dirt that was dug out for new downtown lakes, he said.

Others opposed the whole thing, Healy said, and some wrongly accused him, as the chairman of the Complete Fayetteville Once & For All committee, of advancing the effort for his personal profit.

“And I’ve never owned anything downtown,” Healy said.

The committee recognized that other ideas would emerge than those laid out in Marvin’s maps and drawings, Healy said. “If there was a better idea that made more sense, and certainly an idea that would be funded by private enterprise, we didn’t want to do anything in opposition to that,” he said.

What has the Marvin Plan wrought?

Healy and longtime downtown business owners have thoughts on the Marvin Plan’s legacy.

Back in 1994, there was a lot of negativity, Healy said.

“The vast majority said, ‘It’s dead, plow it under, it’s never going to come back. The town’s moved on from downtown.’

“And we didn’t accept that.”

So they commissioned the plan.

“I think what we did more than anything else is kind of lit a spark that caused a lot of these people, the coffee shop down there and some others to put their money and their life savings into things,” Healy said. “When before there was kind of no hope. You’d have to be some kind of crazy guy to go down there with the buildings boarded up, and it’s abandoned, and it wasn’t a safe place.”

Molly Arnold, owner of the Rude Awakening coffee shop on Hay Street, was a late-1990s pioneer downtown.

She didn’t know of the Marvin Plan before she started, she said.

“It’s not that I don’t have ‘big vision,’ but I tend to be focused on nuts-and-bolts, right, and what really makes it tick, and what you really need to be financially successful,” Arnold said.

She credits the growth of downtown to business owners like her who took risks, invested and worked hard to succeed.

The biggest challenge now is getting the public to realize that downtown extends beyond Hay Street and Person Street, Arnold said. Meanwhile, for some businesses, including her coffee shop, the lack of a hotel to bring visitors has reduced sales, she said.

Fayetteville native and Court of Appeals Judge John Tyson is another longtime downtown investor. He and his family have buildings near the Market House with retail space, office space and two apartments.

Amenities like the Mound that Marvin proposed, and the baseball stadium and the upcoming Crown Events Center, are good to have, and bring people for events, Tyson said. But to succeed, downtown needs people living and working there, he said.

The Marvin plan tied into prior efforts and prior projects to boost downtown, such as the construction of the county library, Tyson said, and the Prince Charles Hotel (which had periods of success back then as a hotel).

“I think it has a positive impact and got people to focus,” Tyson said. “But what I’m saying is: A lot of people were focused on that long before that.”

This article originally appeared on The Fayetteville Observer: Fayetteville envisioned an incredible downtown in 1996. What happened?