6 things to know about the transportation of hazardous materials in the Midwest

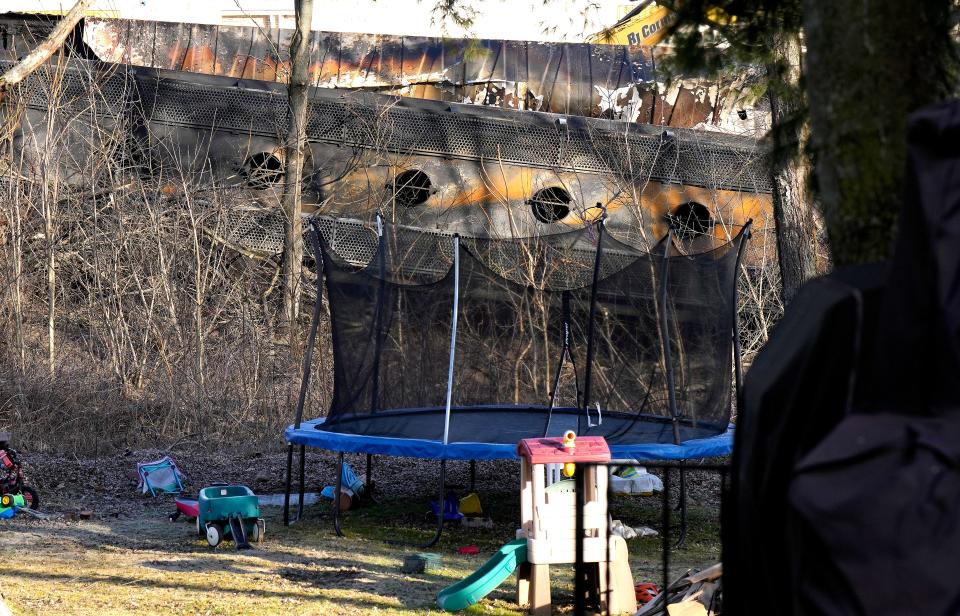

The train derailment in East Palestine earlier this year forced the topic of hazardous materials and their transportation ― topics that previously were of little consequence to the general public ― into the spotlight. A shift happened that day in February, not only for residents of the small Ohio village, but an entire nation.

It exposed gaps in safety practices, spurring calls for enhanced regulation and other changes to prevent accidents. The catastrophe also had people across the country questioning if they are at risk. While the East Palestine incident is an extreme example, a USA TODAY analysis found it is not an isolated incident.

More: Huge amounts of hazardous materials pass through Midwest every day. How safe are residents?

Here are six key findings about the movement of hazardous materials across the Midwest region and country.

Hazardous materials are everywhere

There are more than 1 million shipments of hazardous materials moving across the country every single day. These chemicals are being transported on highways, rail cars, barges and airplanes ― the mode of transportation differs depending on the type of material, the amount and where it's being shipped.

There are nine different categories of hazmats that are classified by their properties, such as corrosive, explosive, toxic, and flammable.

More than 99% of these shipments arrive without incident, according to a former official for the federal Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration. But as the disaster in East Palestine revealed, when there is an accident the outcome can be catastrophic.

Hazardous materials a part of nearly everything

The federal government has determined that hazardous materials are so important to everyday life that it has deemed the chemical industry as “critical infrastructure” along with key systems for communications, energy, banking and healthcare.

One expert in the chemical industry said it's easier to name products that don't involve hazmats than all of those that do ― some are in the item itself, others are involved in the manufacturing process.

Behind the numbers: Hazmat transportation accidents are on the rise in Midwest

Gasoline and diesel, for example, fuel vehicles and generators. Chlorine is used for disinfectants and in pharmaceuticals. Anhydrous ammonia is necessary for fertilizers and refrigerants. Sulfuric acid is used in batteries and paper production. And vinyl chloride ― one of the chemicals released in East Palestine ― is used in the production of plastics such as PVC pipes and kitchenware.

Midwest is a hotspot

The Midwest region is no stranger to hazardous materials. Given the location and the area's strong ties to manufacturing and industry, hazardous materials are transported throughout the region every single day.

With that, it may come as no surprise states in the Midwest also experience a high number of transportation-related hazmat incidents. Just five states ― Illinois, Indiana, Kentucky, Ohio and Michigan ― accounted for more than 20% of the incidents in the U.S. since 2013, according to an analysis of federal data. Three were in the Top 10: Illinois (3), Ohio (4) and Indiana (9).

Rural, low-income communities disproportionately impacted

The majority of hazmat accidents in the five-state region — nearly 90% — occur in urban and suburban counties that include industrial and manufacturing hubs where large quantities of hazardous come and go daily. That said, accident data shows rural communities face an outsized risk when it comes to serious damages.

When zooming in on in-transit accidents deemed “serious” — indicating deaths or injuries, mass evacuations, or large hazmat releases — the portion occurring in rural counties jumps to about 37%. Many of these areas don't have the resources to quickly assess and respond to a potentially catastrophic event.

Even more, a researcher at the Urban Institute said the full picture of the impact on low-income and rural communities is likely greater than county-level data suggests.

Emergency responders

Emergency responders across the region have varying levels of preparedness, depending what type of department they are in and whether they serve on the hazmat team. Many big cities, like Indianapolis, Cincinnati and Louisville have designated hazmat teams that receive significant training and annual recertification.

Other areas, such as smaller cities and many rural locations, often have volunteer fire departments. Those units don't have as many resources for training or equipment. And any training they do receive is often lost in firefighter turnover. Volunteer departments often rely on the larger departments coming to assist, but it can sometimes take hours for them to arrive.

Dwindling funding for hazmat response is affecting all fire departments, according to fire officials. Some departments are even dissolving their hazmat teams because they don't have the funding, according to the Indianapolis hazmat team leader. Those losses further reduce the capacity to respond to an incident.

Regulatory pushback

The transportation and chemicals industries tout their commitment to safety, but they also have a history of pushing back against new regulations. A former Federal Railroad Administration official said the East Palestine incident points to a systemic breakdown and the challenges of improving safety.

Norfolk Southern, which operated the train that derailed in East Palestine, said it want to the the "gold standard" for safety and supports new legislation to improve safety. But Norfolk Southern, CSX and other freight companies also have spent more than $400 million in the past two decades lobbying the federal government, including efforts to ease, rather than strengthen, safety standards. In recent years, railroads also have adopted a new strategy called PSR, designed to boost profits with longer trains and fewer people — both of which can lead to more accidents, according to experts.

This article originally appeared on Indianapolis Star: 6 things to know about the transportation of hazardous materials