When I Was 6, I Thought Doctors Knew It All. Then a Botched Operation Changed Everything.

I was 5, splashing naked in a plastic Smurf pool with my 2-year-old sister, Allyson. We were called inside for lunch. My mother had made my favorite sandwich: pepperoni and mayonnaise on Wonder Bread with the crusts cut off. As she was drying me off, she noticed a lump on the left side of my abdomen, the part she called my groin—a strange-sounding word. It was hard and round, like a large marble. She poked at it, and I yelped.

My mother brought me to a local pediatric surgeon, Dr. X, in the next town over. Upon entering the examination room, he bent down to my height and offered his hand. I shook it like I had been taught.

Dr. X explained that the bump was a hernia, and the repair procedure was simple. All he had to do was make a small incision over the bump, pop it back into my intestinal wall, and finish it off with a few stitches. Afterward there would be candy, maybe a stuffed animal, and a few days sitting at home watching my favorite game show, Press Your Luck.

The operation would leave a two-inch scar that would be easily covered by a bathing suit. Dr. X said that when I got older and grew curly hair down there like my mom, the scar would be hidden forever. Yes, it was surgery, and yes, I would have to go to the hospital, but there was nothing to worry about. He had done this procedure so many times, he could do it in his sleep. I would be running around again in a matter of days, if not hours.

I had been taught to respect doctors. My grandfather had a whole wall of medical degrees, and so did my uncle. My father was also a doctor, though having failed organic chemistry three times and having accidentally splashed nitric acid on his professor’s arm, his specialty was English literature. Doctors were experts.

The morning of the procedure, my sixth birthday, my parents lifted me up on a gurney and sent me off with a flurry of kisses. I wasn’t scared. Having an operation made me feel special.

The only thing I was sad about was that this was outpatient surgery, so I wouldn’t stay overnight in the children’s ward like they did in the Berenstain Bears book. It was a place rumored to offer endless bowls of raspberry sherbet.

Under bright light in a white-tiled room, I fiddled with my plastic ID bracelet, spinning it around my wrist. I looked at my name printed underneath the plastic and thought, I am an Anya. Today is my birthday. Six years ago, I became me.

Dr. X entered the OR and glanced down at me. The light made his scalp shine. I smiled at him, but he didn’t notice. He kept rubbing his nose. A nurse asked him if he was all right.

Dr. X nodded.

“You sure?”

“Let’s just get this over with.”

A man holding a green mask that was attached to a vacuum hose approached the table. He placed a ring of plastic over my mouth and told me to breathe. The air smelled like hot toilet-bowl cleaner and rotting Christmas trees. He told me to count backward from 10. The room wobbled at nine, melted at eight, and collapsed by seven.

I woke in the dark. Not the kind of dark that accompanied Dr. Seuss stories and monsters under the bed. This dark burrowed under my toenails. I was buried alive, locked in a kid-sized coffin, contemplating solitary evermore. For the first time, I was completely alone, just a brain floating in a puny body, fully independent of parents, sister, dog, and cat.

Then, pain. Pummeling.

Not in my abdomen, as the doctor had told me to expect, but in, from, and about my right leg. Maybe I had been carved up like a Thanksgiving turkey on that operation table. Maybe some greasy adult, hungry for a child limb, had pulled my leg out of my socket. Maybe they were munching on it in the corner now.

People were eating me.

As the pain became sharper, so did my vision. I could now discern the tacky pattern of the tile on the walls, feel the starched sheet under my chin, and see a sliver of fluorescent light seeping in from under what I slowly concluded must be a door. Against all evidence to the contrary, apparently I was still alive. I screamed and nurses came running. They sat me up and gave me apple juice in a minty-green-colored cup. I had no words, only shrieks. Eventually, my parents lifted me into the back seat of our gold Chrysler K-car. I shrieked the whole way home. I shrieked when they lifted me into my bed. I shrieked in my sleep.

Or I think I shrieked.

Inside I was shrieking, though it’s possible I might not have made any sound at all.

Inside I am still shrieking.

My parents seemed paralyzed by my complaints, and I couldn’t figure out why they were just sitting there on our sofa with worried looks on their faces. Why hadn’t anyone told me about this? Did they think I wasn’t old enough to know if this was supposed to happen? And why was everyone whispering on the telephone? Couldn’t somebody just explain what had happened in that operating room? Did I do something wrong?

Though I had an impressive vocabulary for a 6-year-old, I struggled to find the words to explain how I felt, and after a while, I gave up. My parents were right in front of me, and no matter how hard I cried, they seemed unable (or was it just unwilling?) to hear me. Actually, they seemed a little afraid of me, like I had just turned into a monster right smack in their living room. Allyson heard me though. She crawled into my bed and held my hand.

“You can have my Cabbage Patch,” she said, offering her baby doll, Clarissa Joya. I snuggled Allyson close and imagined my pain was a thick chocolate milkshake. I tried to slurp it as fast as I could, willing to accept all the ice cream headaches in the world as the price of reprieve. It didn’t come.

Five days later, when it was time to go back to school, my dad picked me up off the couch and set me on my good leg. I fell down. He had me try again. This time, I managed to teeter for a few moments.

“See, you just have to stop being afraid. You just need to try.”

I was trying. I was always trying. If there is one thing I can say about myself with certainty, it is that I have always tried.

I overheard my dad on the phone to Na, my grandmother.

“She seems to be getting worse. She’s walking a little now, but still says she is in pain. Ma, I don’t know what to do.”

A week later, my mother took me back to Dr. X’s office to have my stitches removed. I limped into the examination room. I told him that my leg felt like someone pulled it off.

Dr. X’s nostrils flared.

“Don’t be melodramatic. Don’t make up stories. This isn’t a movie.”

“But she seems to be in a great deal of pain. My husband has to carry her up the stairs and she’s limping. She never limped before.”

The doctor said he saw it all the time. A child gets attention for having surgery and is indulged for a few days. They don’t want to give up being the patient, watching cartoons, and missing school. So they exaggerate, make up ailments that don’t exist. In short, they manipulate and prey on parents’ emotions and guilt.

I wasn’t sure what “manipulate” or “prey” meant, but I picked up that I was in trouble. I had felt special going into the OR. Dr. X must be right. I did something wrong and now my leg was my punishment. I’d never been punished before.

My mom conceded that I did have a flair for the dramatic. “But,” she said, “she is not a child who lies.” Her voice was clearer, louder this time.

“My advice is to stop letting Anya make a fool out of you. She’s pulling a grade-A swindle, manipulating you. Tell her she’ll never get a Happy Meal again; tell her no more Barbies. Punish her for lying, especially for lying to me.” Dr. X told me to pull off my panties. He placed his hand on my groin, grabbed a pair of tweezers and plucked out the thatch of stitches. I looked down. A blistered line stretched from my hip to the middle of what I would one day call my bikini line. He pressed his forefinger down on the cut and looked me straight in the eye. “Good girls don’t lie.”

I nodded yes and sucked on my imaginary milkshake.

Over the next three months, my leg felt tethered to a runaway train, its sinews and tendons perpetually pulling away from my body. I tried to ride the bicycle I got for my sixth birthday, but I couldn’t get my leg over the crossbar. I struck out in gym class so I wouldn’t have to haul myself around the bases. I couldn’t climb up to the monkey bars and I couldn’t pump my legs on the swings anymore, so I sat alone at a picnic table at recess.

Honestly, I was already uncomfortable in school. I was weird. My T-shirts identified me as a fan of Antietam National Battlefield, the periodic table, and Mr. Wizard. I carried a PBS tote bag. Kids rooted for the Yankees over the Red Sox, the Rangers over the Bruins; I rooted for WNET over WGBH. I wrote with pencils my mom gave out in her classroom, which were imprinted with goofy science jokes about what the proton said to the electron. I mismatched Velcro Zips sneakers in cheetah- and leopard-print patterns that we got from the clearance rack at Marshalls with triple-tiered peasant skirts hand-stitched by my mom. Occasionally, I topped my outfits off with my personalized Mickey Mouse–ears hat. My fashion inspiration was a little Punky Brewster, a little Murder, She Wrote, with a dash of Dynasty for shimmer.

As winter was closing in on southern Connecticut, my mom discovered another bump in almost the exact same place the other one had appeared. My parents took me to a new pediatrician, who took one look at me limping into the examination room and told my parents they had a serious problem on their hands. Sudden unexplained muscle loss was a medical emergency, forget the hernia.

I had been right; I had been right. But what was it about my voice, the only one I had, that kept them from hearing me? Why did my parents believe this new doctor but not me? Was it because he was an expert? I had already learned that these experts couldn’t be trusted, and most devastating, I was now learning that my parents might not be trustworthy either. I’d become so used to keeping my pain hidden that now almost everything didn’t feel like anything. I was numb, everywhere. I was Han Solo frozen in carbonite.

Though cancer was initially suspected, my blood tests were all negative and my scans clean. Meanwhile, my leg got worse. I had no reflex at my knee or under my foot. My muscles had atrophied severely, and eventually the muscles in my right leg were just two-thirds the size of my left. Doctors stuck needles into my leg and used electric current to try to stimulate it. I felt nothing. More ultrasounds, CT scans, X-rays, sonograms. When I wanted to walk, I had to repeat to myself, Move, leg, move. Move, leg, move, and slowly the maimed limb would toddle behind me.

It took the brilliant minds at Yale New Haven Children’s Hospital to uncover that the incision from the first operation was a full two inches below the actual hernia, which had not even been repaired. Dr. X had mysteriously mistaken my femoral nerve for the tissue around my hernia, and his sutures, meant to bring together his incisions, had been instead sewn through the nerve, slicing almost completely through it. The doctors estimated that I had only a few weeks before I would permanently lose most of the use of my leg. I needed another surgery, which would be much more complex and much riskier this time.

Sitting alone in my hospital bed the night before the operation, I took Crayola markers and drew instructions for my doctors on my right thigh. I couldn’t feel the markers as they slid across my skin, but I marked my body like a map, circling my hernia in red and adding arrows and exclamation marks. I drew connecting lines to my leg in orange and green. I drew lopsided purple stars along my groin. I wanted there to be no doubt about where and what the doctors should fix. Those markers were defensive weapons. This time, I was the expert. (This discovery of marking my body, of using my body as my voice, would become integral to my life as an artist in the years to come.)

A different man holding a green mask asked me to breathe in hot toilet-bowl-cleaner air, and eight hours later, the operation was deemed a success. The surgery was also historic. It was one of the first nerve reconstruction cases of its type in the world, and was written up in pediatric neurology textbooks and journals. It had a secondary, and in my view more important, takeaway: When considering pediatric cases, listen to young patients. Though they may not be able to fully express what they are feeling, their complaints should be carefully considered and explored.

For the next two years, my mother carted me back and forth to Yale for physical therapy. As a special treat for enduring the appointments, we ate chicken nuggets with double BBQ sauce at the West Haven Wendy’s just off I-95. Eventually, my office visits decreased to once a month, as long as I exercised rigorously every day. I chose ballet, simply because my other option was playing on the town’s super competitive travel soccer team. Since those girls had been so mean to me when I couldn’t walk properly, it wasn’t an option.

And I danced and I danced and I danced. At first, I did it only because the doctors told me that unless I wanted to walk with a cane for the rest of my life, I had to move my body daily, no matter how much it hurt. Then I did it because ballet class was one of the few places where I wasn’t bullied for being smart or for wearing strange clothes or for not being able to afford to take fancy vacations. Then I did it because of George Balanchine, co-founder of the New York City Ballet. Though he had died in 1983, I was taught by two of his dancers, Carol Sumner and Edwina Fontaine, and I became obsessed with his technique and choreography. While other kids my age were at home playing Nintendo, every afternoon Carol and Edwina taught me that real, true artists had a higher calling—to turn our bodies into the most finely tuned instruments in the world. Childhood was for children, they said, but ballet, real ballet—not “Dolly Dingle strip-mall ballet”—was for aspiring immortals. Balanchine gave me the opportunity to subvert the inexplicable violence that had occurred to my body, a chance to be transformed.

Because of the constant, intense training, my right leg eventually regained its strength and reflexes, but I never regained any feeling in my thigh, and my limp took longer to disappear. There was a malpractice lawsuit and a settlement. Dr. X had (allegedly) been snorting lines of cocaine before my surgery, but it was hard to feel vindicated when I saw how guilty my parents felt. They had only done what they thought was best. I didn’t confront my anger; I buried it in my milkshake.

But milkshakes melt, and when they do, they make messy puddles. For so long, I forced myself to believe that what had happened was really for the best because it led me to dance and art and performance. It taught me that I could overcome any challenge placed in front of me! That all I must do is believe in myself! That hard work leads to great things! That perseverance is everything! All of that may or may not be accurate, but it’s certainly true that I could have found it out without having to have my leg mangled in the process.

Although of course, it’s also possible that I appreciated the language of dance, the voice in the silence, more than others because I came so close to losing so much of my mobility.

Dance was a language that loved me back because it fully honored all my experiences. The scars and the weakness that still lived in my body’s kinetic archive became the seeds of developing my own aesthetic systems and iconography. Which is just a lot of blah, blah to say that it’s taken me a long time to realize that the way I made meaning out of all of this nastiness was by becoming an artist.

It was a survival strategy.

Dr. X tried to silence my voice, but through ballet, it grew back.

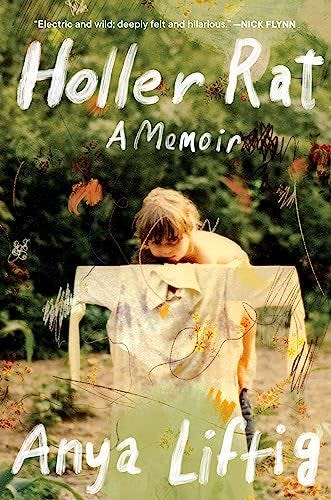

Excerpt from the new book Holler Rat by Anya Liftig, published by Abrams Press ©2023.