60 years ago, Columbus, Westerville residents marched for still elusive freedoms| Jeffries

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Judson L. Jeffries is professor of African American and African Studies at Ohio State University and a regular contributor to the Columbus Dispatch.

August 28, 1963, two months after NAACP leader Medgar Evers was assassinated in the driveway of his home in Jackson, Mississippi, approximately 250,000 freedom-loving people from all over world descended on the Washington Mall.

More: 1963 March on Washington almost overlooked women

Out-of-towners arrived by car and bus, while others came by air and train. The March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom was up to that point, the largest U.S. civil rights movement demonstration ever witnessed.

According to the Columbus Dispatch, of that quarter million people, nearly 200 were from Columbus, Westerville and other Central Ohio, locales.

On Tuesday, August 27, 1963, residents climbed aboard no fewer than six chartered buses bound for the nation’s capital. Among the throngs of bus riders were representatives from the Columbus chapter of the Congress of Racial Equality and the NAACP, two of the city’s most prominent civil rights organizations, and movement’s most effective groups.

Members of the Catholic Interracial Council of Columbus were also present. In an act of symbolism, the march was held 100 years after the signing of the Emancipation Proclamation.

March on Washington: What racial equality means through the eyes of Columbus 13-year-old

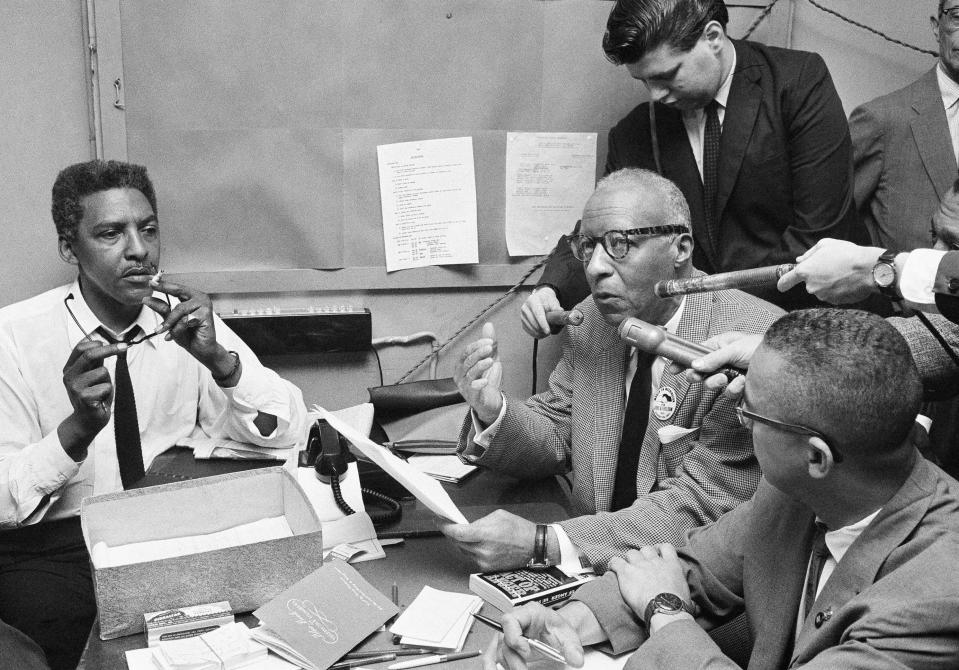

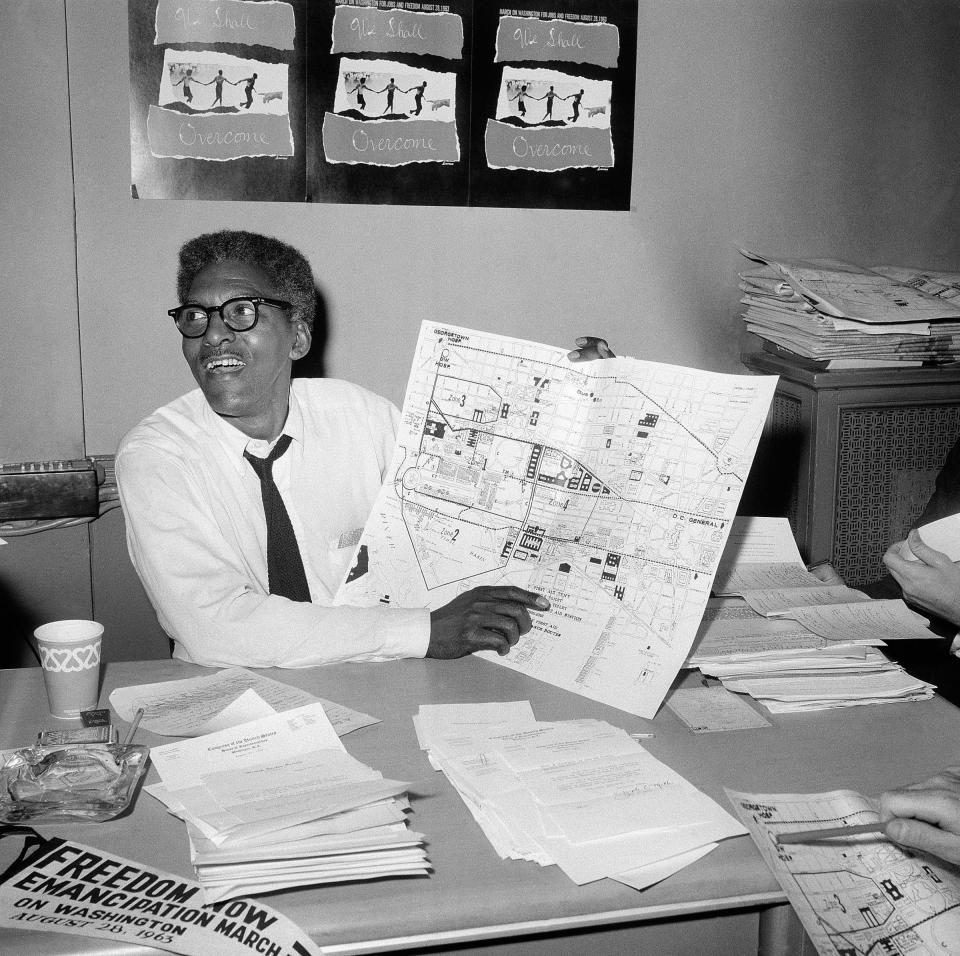

Although history has recorded Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. as the face of that landmark event with his “I Have a Dream Speech," it was political strategist Bayard Rustin, formerly a student at Wilberforce University many years earlier and one of the illustrious Omega Psi Phi Fraternity’s most heralded members who was the event’s principal organizer.

Rustin was a seasoned activist, known for his extensive experience putting together mass protests, having worked alongside the venerable Ella Baker with the Crusade for Citizenship in the early 1950s, serving in various capacities as a member of the Fellowship of Reconciliation in the 1940s, the Journey of Reconciliation in 1947 and the War Resisters League, to name a few.

The iconic Rustin handled the logistics for the March, going so far as to put together an organizing manual for grassroots activists around the country for the purpose of mobilizing their communities and ensuring safe and timely travel to and from Washington, DC.

Although the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom was a milder version of what its progenitors had initially planned, it served as a call to action especially among the country’s young whites.

The following year saw several hundred young whites travel to Mississippi and participate in Freedom Summer. There they joined African American civil rights activists in the fight against voter intimidation at the registrar’s office and at the polls.

Sixty years ago, less than 10 percent of Mississippi’s Black voting age population was registered to vote. The country’s southern states, especially those in the deep south had a long history of disenfranchising Blacks and poor whites via an array of imaginative if not absurd laws, state constitutions and other measures.

Last Saturday, thousands of people from all over gathered on the National Mall on a hot and balmy day in recognition of the march’s 60th anniversary. Some spoke to reporters, reflecting on the state of America since 1963.

As for full employment and freedom and justice for all, those ideals remain as elusive today as they did sixty years ago.

Judson L. Jeffries is professor of African American and African Studies at Ohio State University and a regular contributor to the Columbus Dispatch.

This article originally appeared on The Columbus Dispatch: Did Columbus residents play a role in March on Washington? Who is Bayard Rustin?