60 years after ‘I have a dream,’ where do MLK’s hopes for Black homeownership stand?

In February 2020, Tenisha Tate-Austin and Paul Austin decided to erase all traces of their existence in the Northern California home the Black couple had created for themselves and their children.

They “whitewashed” their home by removing their family photographs and African art displayed around the house. They had a white friend place some of her own family photographs around the home and greet the appraiser as if she were the homeowner.

The couple wanted to see if they’d get a better home appraisal than the one they had received three weeks earlier.

The experiment worked. This time, the appraisal (by a different appraiser from the same appraisal management firm) was almost 50% higher. In three weeks, the value of their Marin City home, 11 miles north of San Francisco, had gone from $995,000 to $1,482,500.

In March, the Austins settled a fair housing lawsuit alleging race discrimination against the licensed real estate appraiser; they'd reached a settlement in October with the appraisal management company.

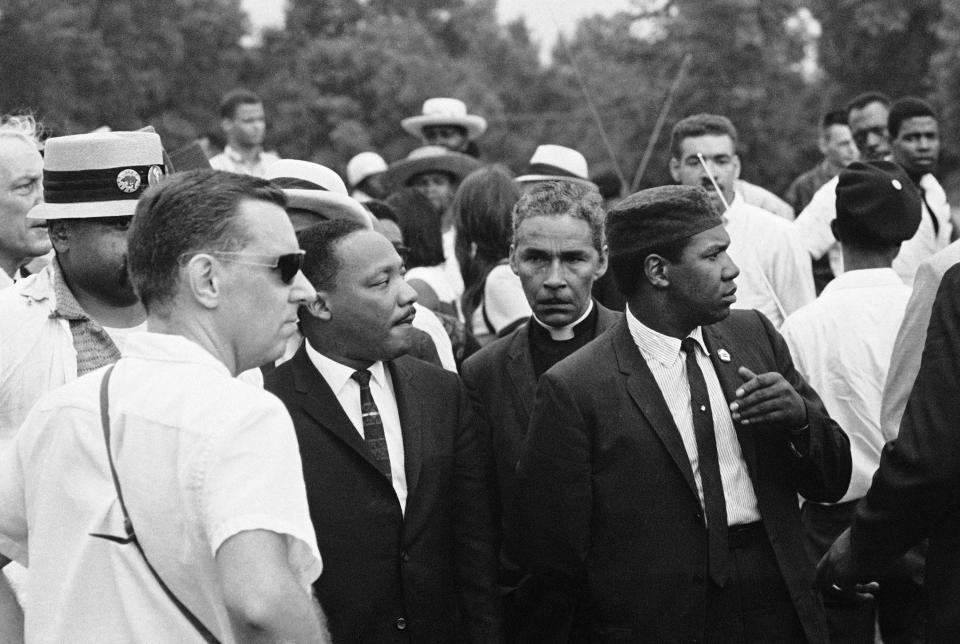

Sixty years after Martin Luther King Jr. delivered his most iconic speech calling for civil and economic rights and an end to racism, one of the biggest roadblocks to building wealth for Black Americans is still in place: The housing gap has widened from the time it was legal to discriminate based on race.

In 1960, eight years before the Fair Housing Act, which prohibits property owners, financial institutions and landlords from discriminating based on race, the homeownership gap between white (65%) and Black (38%) stood at 27 percentage points. In 2021, or 60 years later, that gap had grown: 73% of white households owned a home compared with Black homeownership at 44%, a difference of 29 percentage points, according to the Urban Institute.

“We missed out on a better interest rate because of the unfair appraisal we received,” Tenisha Tate-Austin said in statement through her lawyer. “Having to erase our identity to get a better appraisal was a wrenching experience. We know of other Black families who either couldn’t get a loan because of a discriminatory appraisal and therefore either lost the opportunity to buy or sell a home, or they had to sell their home because they had an unaffordable loan.”

Explore the series: MLK’s ‘I have a dream’ speech looms large 60 years later

Housing gap: 'We are a broken people': The importance of Black homeownership and why the wealth gap is widening

King fought racist housing practices in Chicago

Though King knew housing was an important topic when he made his 1963 speech (it included the line "We cannot be satisfied as long as the Negro's basic mobility is from a smaller ghetto to a larger one," his focus was ending segregation in the South, said Beryl Satter, professor of history at Rutgers University in New Jersey and author of "Family Properties: Race, Real Estate, and the Exploitation of Black Urban America."

“The speech was about jobs and ending segregation of drinking fountains and restaurants, buses, trains, movie theaters and swimming pools to help pass the Civil Rights Act,” she said.

Once that was accomplished, King trained his sights on housing in the North, particularly Chicago, where he focused on enforcing a pre-existing law on open housing, Satter said.

The open housing laws in Chicago already forbade real estate agents from steering Black families into Black neighborhoods and dictated that housing should be made available regardless of race.

"But like many such open housing laws, it was not enforced," Satter said.

In January 1966, King moved with his family into an apartment in North Lawndale on the West Side of Chicago to bring attention to the poor living conditions of Black families living without water, electricity and heat. He marched with Black and white supporters into segregated white neighborhoods to call for open housing.

“And there he was met with the most violence he had ever been met with in any of his civil rights struggles. He said that the violence in Chicago made the whites in Mississippi look good,” Satter said. “He was hit with a stone while marching in Chicago, and he kept going.”

Fair Housing Act became law after King’s death

From 1966 to 1967, Congress regularly considered a fair-housing bill, but it was ultimately defeated.

“It was the first time that a Civil Rights Act had been defeated since the '50s,” Satter said. “There was massive white resistance to any law or direct action that threatened racial segregation and housing. It was something that whites in the North fought to the death to keep.”

After King was assassinated in 1968, President Lyndon Johnson pushed through the national Fair Housing Act as a memorial to King, whose name had become closely associated with the fair housing legislation.

The undervaluation of homes in Black neighborhoods, decadeslong housing segregation, a systemic denial of loans or insurance in predominantly minority areas, a persistent income gap, and a historically limited ability of Black parents to leave their families an inheritance have contributed to the nation's financial disparity, experts say.

During the housing boom of the early 2000s, Black Americans ages 45 to 75 disproportionately held subprime mortgages, loans offered at higher interest rates to borrowers characterized as having tarnished credit histories. Many of these mortgage holders lost their homes and have been unable to return to homeownership.

These trends will affect retirement prospects for Black Americans and their ability to pass down wealth to the next generation, making it not just one generation's problems but an intergeneration disparity, experts say.

White wealth surpasses Black wealth

In 2016, white families posted the highest median family wealth at $171,000. Black families, in contrast, had a median family wealth of $17,600, according to the Federal Reserve. Homeownership has long been considered the best path to build long-term wealth, so increasing the rate of homeownership can play an important role in closing the wealth gap, experts say.

Over the past decade, the median-priced home in the United States gained $190,000 in value, making the typical homeowner 40 times wealthier than if they had remained a renter, according to a report released in April by the National Association of Realtors.

Some signs of hope emerged during the coronavirus pandemic, when mortgage rates were at historic lows.

During that time, Black homeownership rates increased by 2 percentage points, surpassing the white homeownership rate, which increased just 1 percentage point.

The historically low mortgage rates enabled high-earning, highly educated Black households to boost homeownership rates. Most high-income white households already were homeowners, which explains the smaller magnitude of growth, according to the analysis.

Black homeownership rate saw small improvements

From 2019 to 2021, the homeownership rate for Black households went from 42% to 44%; for white households it went from 72% to 73%.

After experiencing a continuous decline since the Great Recession, the Black homeownership rate finally made gains between 2019 and 2021. The reason was pent-up demand, said Jung Choi, a researcher at the Urban Institute.

"This suggests that affordability really matters,” Choi said. “Now, with the surge in interest rates, we are already seeing a sharp decline in Black homebuyers as well as younger homebuyers.”

Satter said King's final book, 1967's "Where Do We Go From Here: Chaos or Community?" cautions against complacency simply because there are laws on the books.

“He really understood that having a law in books was the beginning, not the end. Today we have the Fair Housing Act of 1968, and there are ongoing local, state and national laws that are supposed to stop housing discrimination,” Satter said. “I think King would have predicted that they would not be effective if there wasn't a larger public will to enforce it and a strong political organization pushing to enforce it.”

Swapna Venugopal Ramaswamy is a housing and economy correspondent for USA TODAY. You can follow her on Twitter @SwapnaVenugopal and sign up for our Daily Money newsletter here.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Housing gap continues to target Black homeowners, compounding inequity