60 years on, dwindling witnesses to John F. Kennedy assassination keep story alive

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Nov. 22 (UPI) -- Sixty years have passed since news broke across the UPI newswire that President John F. Kennedy had been shot in Dallas. While many witnesses to that dark episode of American history are gone, the few who survive are working to keep the story from fading away.

"Kennedy seriously wounded perhaps seriously perhaps fatally by assassins bullet," the transmission from veteran UPI reporter Merriman Smith read.

The president of the United States and Texas Gov. John B. Connally had been shot by a sniper, as Smith described. Three shots rang out in Dealey Plaza on Nov. 22, 1963. Smith would later break the news confirming Kennedy's death.

The 60th anniversary of Kennedy's assassination differs from past milestones that marked the passage of another decade, Stephen Fagin, curator of the Sixth Floor Museum at Dealey Plaza, told UPI.

"We reach this juncture now where memory is fading into history," Fagin said. "We've reached this juncture where only one homicide detective is left. He's 96. Only a couple of Parkland doctors are still around today. It makes me aware, very acutely, that this is slipping further and further away from us."

Yet, firsthand accounts persist, both in the words written by Smith and in those who remain to tell the story of one of the most impactful moments in U.S. history.

Merriman Smith's reporting

Smith, UPI's reporter on the ground, tightly gripped a radio telephone from the pool car in the president's motorcade as it rolled down Elm Street in Dallas. He fended off other reporters in the car as he shared his account of what he observed with UPI Southwest Division Manager Jack Fallon, said Bill Sanderson, author of Bulletins From Dallas: Reporting the JFK Assassination.

"Bulletin precede," Smith yelled into the phone, indicating that this was now the top story of the day. Four minutes after the shots were fired, the UPI bulletin spread nationally and was read by Walter Cronkite on live TV.

Smith stayed on the story as it continued to evolve, racing through the halls of Parkland Memorial Hospital to find another phone and boarding Air Force One to witness the swearing-in of President Lyndon B. Johnson.

At each turn, Smith knew where to be, who to talk to and what details to share with readers, Sanderson told UPI.

Smith finished that day in Washington, filing his eyewitness account of the assassination, which would win a Pulitzer Prize.

His 20-plus years as a White House reporter prepared him to be "the man" on that day, Sanderson said.

"He understood the beat better than anyone else," Sanderson said. "What Smith was able to do was within the first half-hour or so manage to file enough copy -- or give enough reporting to the rewriter, to be able to get a pretty coherent story on the wire. That was important in those days."

Smith wrote his story from a first-person point of view, which is less common today. But rather than expressing how the events impacted him, he detailed the weight of the moment in his observations of others, such as his depiction of Kennedy associate Theodore C. Sorenson.

"Sorensen sat wilted in the large chair, crying softly. The dignity of his deep grief seemed to sum up all of the tragedy and sadness of the previous six hours," Smith wrote.

Reflecting on Smith's reporting highlights how the world has changed. Sanderson recalls afternoon editions of newspapers, which have become nearly extinct. These afternoon editions brought Smith's reporting to newsstands nationally, delivering the news of Kennedy's assassination ultimately to the world.

'The weight of the world'

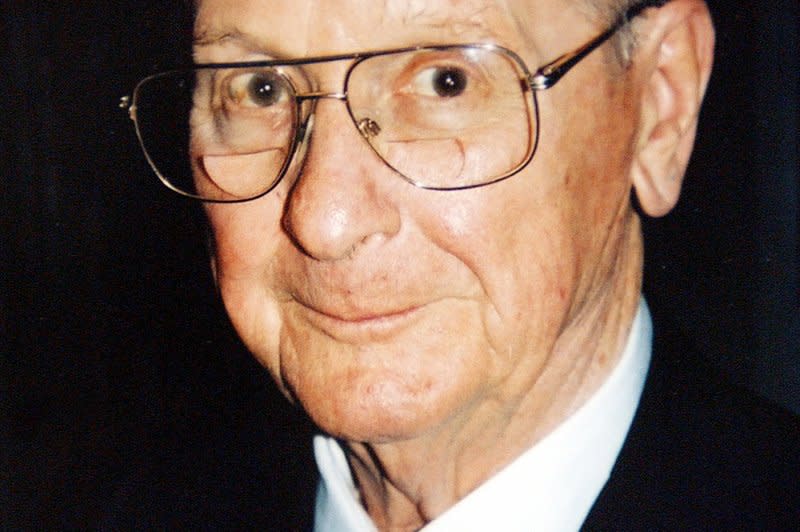

Darwin Payne was in a much different place in his journalism career than Smith on Nov. 22, 1963. While Smith was the most veteran White House reporter of the day, Payne was a 26-year-old reporter with the Dallas Times Herald.

He had a few years of experience under his belt, having served as the wire editor for the Fort Worth Press, where he exclusively handled UPI copy. But on that day he was thrust into the biggest story of his life, he told UPI.

The newsroom had been preparing for Kennedy's arrival for a few days. He had made stops in San Antonio and Fort Worth, but Dallas promised to be an even bigger event.

Payne's assignment was to be the "rewrite man" for a sidebar on first lady Jackie Kennedy -- one of several angles to be covered that day. A reporter was sent to the Dallas Love Field airport to relay the depiction of her arrival to him.

"There was a lot of excitement about Jackie those days," Payne recalled. "She wore a beautiful raspberry dress with black trim, a pillbox hat. The crowd went wild over her."

Now 86, Payne remembers a foreboding feeling in the newsroom leading up to JFK's arrival. Dallas had become the site of demonstrations by what he called "ultra-right wingers" who one month before had accosted U.N. Ambassador Adlai Stevenson, hit him with a sign and spat on him.

"It was worse than anyone ever pictured it as," Payne said. "I expected and feared something would happen as it did."

Several officials urged Kennedy not to come to Dallas, including ministers, the Dallas Citizens Council and U.S. District Judge Sarah T. Hughes. She later swore in Johnson as president aboard Air Force One hours after Kennedy's arrival.

Despite the trepidation, it was a welcome procession, according to Payne, up until the first shot rang out at 12:30 p.m.

When word came across of the shooting, Payne was told to abandon his first lady story and race to Dealey Plaza.

"I felt the weight of the world," he said. "I felt that this would be the story of my life, no matter what happened. I was feeling that things could've not been what we thought they were. They might've missed him."

He was devastated to learn what had happened in his hometown, but knowing he had a job to do helped Payne make it through a difficult day.

When he arrived at the plaza, Payne found everybody in tears and a lot of confusion about what they had witnessed.

"Most people knew the president had been hit. There was no doubt about that," Payne said. "The ones I centered on the most, because they were crying the most I suppose, were three or four women who worked in the manufacturing facility across the street from the school depository."

The women led Payne to Abraham Zapruder, the owner of a nearby clothing manufacturer who captured the assassination on 8mm film. He attempted to persuade Zapruder to come with him to the newsroom to develop the film. Zapruder refused, saying he would only submit the film to the FBI or Secret Service.

At about the time Payne had left Zapruder, his newsroom learned that police officer J.D. Tippet had been fatally shot by the gunman.

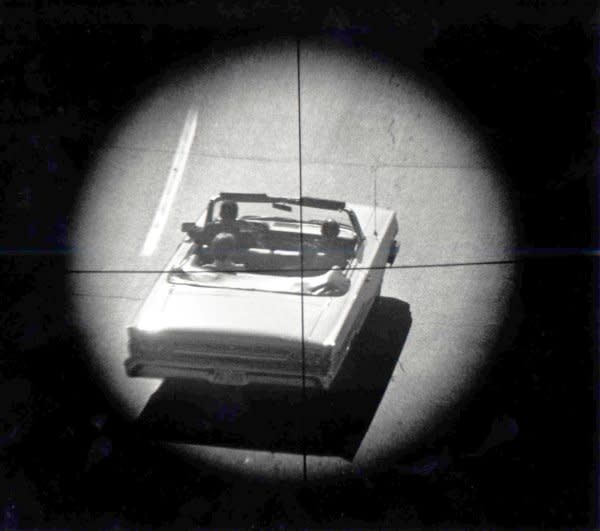

Payne then toured the book depository where the shots that killed Kennedy originated. He peered through the window that Lee Harvey Oswald looked through as he fixed his sights on the president's vehicle.

"It was a very eerie feeling, knowing what we were seeing," he said. "We were seeing what the assassin saw looking out the window."

He then saw where the rifle was recovered and listened to the superintendent of the book depository discuss one person that was missing from his work staff that day. That person was Oswald.

After a brief trip to the newsroom, Payne was off to a rooming house where the suspect lived. He spoke with tenants who described the man they knew as O.H. Lee as a "loner" that "didn't mix with anybody."

Payne continued to canvas the rooming house before returning to the newsroom at about 10 p.m. He expected he would have to give up his notes to another reporter but that reporter told him the story was his.

Last month, Payne's book Behind The Scenes: Covering the JFK Assassination, was published.

'Two Days in Texas'

The Sixth Floor Museum at Dealey Plaza is hosting a special exhibit to commemorate the 60-year anniversary of Kennedy's assassination. "Two Days in Texas" will be on display through June.

"We look at the different cities and people he encountered through photos and artifacts," Fagin said.

The exhibit features several artifacts that have never been on display to the public. One such artifact is an Eastern Airline sign that was displayed on the sky stairs that the Kennedys descended after arriving in Dallas. The same sign remained on the stairs just a few hours later when Kennedy's casket boarded the plane to D.C.

"I find it to be very evocative. It represents how quickly world history changes and its devastating impact," Fagin said.

Fagin hosted a conversation with Payne on Friday, one of several special events focused on telling the story of one of the darkest days in U.S. history. With witnesses to the assassination and the events that followed becoming fewer as time passes on, it falls to historians, educators, people like Fagin to keep the story alive.

"An anniversary like this, I recognize this as the last major anniversary where the storytellers will be here," he said.