$60K retreats and a metal detector: How one family fought a vape addiction

He was going off to high school. An all-star Anderson Township kid. A Boy Scout. A varsity wrestler. His parents said he was obsessed with the sport, constantly watching videos and preparing for matches. He was also on the football team and got good grades. He had a girlfriend. He was kind and polite. A good kid.

"Then, boom," his mother, Hagit Sunberg, said. "He completely walks away from all of it."

Her husband, Jeff Sunberg, put it less delicately: “It’s all gone to hell.”

It wasn't a boom but a puff − hundreds of puffs, actually, as their son became addicted to vaping. The boy's downward spiral has sent his father on a crusade against Big Tobacco, left his mother in a constant state of worry and cost the family hundreds of thousands of dollars in therapy and treatment programs that haven't worked.

The Sunbergs' son, whom The Enquirer is not naming to protect his privacy, is not alone. More than 1 in 3 Ohio high schoolers have tried vaping, according to a 2021 survey backed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. And nearly 1 in 5 students currently vape. That's in line with national survey results.

Vaping health risks: Here's what it does to young bodies

An Enquirer investigation found the issue is widespread in local schools, where hundreds of kids − some in elementary school, even − were caught last school year vaping nicotine and cannabis products. There’s little oversight or repercussions for the shops who sell to minors or the companies who market to youth, The Enquirer found. And while vaping is still too new to fully forecast its long-term health effects, developing research points to lung disease, high blood pressure, headaches, mood disorders and other health risks for youth.

[ The Enquirer is making this special report on the youth vaping crisis free as a public service. Support local journalism with a subscription. ]

But nicotine companies are making too much money selling to children to back down, Jeff Sunberg suspects. And now his family must suffer the consequences of tobacco lobbyists' win.

“We’re fighting a losing battle,” Sunberg said.

From star athlete to vaping addiction

Jeff Sunberg remembers the first vape puff he saw in his Anderson Township home. His son had just finished eighth grade, and he had a friend over who brought the vape and took a hit in the family’s living room.

Sunberg saw the vape cloud from the next room and was furious.

“You don’t bring that into my house,” he recalls telling the friend. “You don’t bring that around my son.”

Vaping in Ohio: Vape juice can kill kids. A vaping law's slow rollout left them at risk of nicotine poison

Four years later, the Sunbergs have a hard time guessing how many vapes they’ve found in their home. The ballpark is around 50, they said, mostly hidden in their son's room in clothes, his backpack and desk drawers. But there were likely dozens of vapes they didn’t find.

The vapes smell "like a pungent, sour fruit," Jeff Sunberg said. Outside of their son's bedroom, they sporadically found his vapes under the bathroom sink, in the china cabinet, hidden in the basement and outside.

Hagit Sunberg said she didn’t know her son had vaped in middle school until years later. She became aware he was using in his first two years of high school and said she realized it had progressed to an addiction during his junior year.

"He had such a promising future," she said.

Jennifer Hoffman, a nurse who runs a vaping prevention program with local students through the Talbert House, said the organization was shocked by how many students are addicted to vaping.

From the editor: Why The Enquirer spent 6 months investigating teen vaping

"An adult who is quitting cigarettes, typically they have a medication or they have nicotine replacement therapy. Some of them have, even, counseling. And they still have issues being successful and productive through their work day," Hoffman said. "Kids are no different. Kids are struggling with addiction and (are) dependent."

The Sunbergs' son had always earned A's and B's, but junior year he started coming home with C's and D's.

During a wrestling competition, his parents couldn't find him in the stands cheering on his team or off preparing for his own match. His dad went looking for him and found him in the bathroom vaping with friends.

At one point he was suspended and wasn't allowed to wrestle at all for a while.

One night he left money in the family's mailbox. Friends came by overnight and traded the cash for vapes.

What had started as a social activity became a solo one. His parents found him vaping alone in his bedroom.

"Everything was destroyed," Hagit Sunberg said.

She said she watched as her son lost interest in everything he had once loved. He only cared about one thing: vaping.

"He consumed it and it consumed his life," she said.

Through it all, the Sunbergs said their son never had issues with alcohol or other substances. And he never got into trouble with the law.

"He never got in a fight. He never got in trouble for anything else," said Hagit Sundberg, a former investigative reporter for WCPO-TV. "His teachers and principals would tell you he's a sweet kid. I mean, he was not a troublemaker."

They know he purchased vapes while underage without using an ID − because he doesn't have one, he never got his driver's license − at the vape shop down the street from Nagel Middle School. Jeff Sunberg said it's "not just a coincidence" that the shop is located there.

"It's a business model," Jeff Sunberg said.

The Enquirer found 177 Greater Cincinnati vape stores that have been cited by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration are within a 1-mile radius of a middle or high school. That's 59% of all stores cited in the region.

It's an open secret the shops don't card, the Sunbergs said. The couple went to the sheriff's office only to find the department knew about the underage sellers and couldn't do much about it.

"They were just as frustrated," Hagit Sunberg said. "They'd been there again and again and they knew what was happening. They knew that this place wasn't carding. They were running stings on that place."

The store is still open.

Parents go to great lengths to protect son from vaping, to no avail

The Sunbergs said their son mostly smoked nicotine vapes, but they know through drug tests – Jeff Sunberg took to testing his son daily at one point – that he tried THC, too.

There are several different types of vapes, many of which can be camouflaged in a student's backpack by looking like a highlighter or a USB drive, invisible to the untrained eye of most parents and educators.

But the devices are no longer invisible to Jeff Sunberg.

“It’s created a detective out of me,” he said. “I’m constantly on alert. I don’t trust him. I don’t trust his friends.”

Because of his son's addiction, Jeff Sunberg has spent the last several years researching Big Tobacco, writing letters to Ohio Gov. Mike DeWine and tracking his son's every move.

DeWine has been outspoken in his desire to ban flavored vapes, which many believe is the crux of kids’ addiction. Educators, medical professionals and kids themselves told The Enquirer that if flavored vapes were off store shelves, they’d quit. But Ohio bills to address the problem head-on by banning flavored vape products didn’t even make it to DeWine’s desk.

Jeff Sunberg believes that's the case for his son, too. He's found mango, strawberry and fruit punch flavored vapes in his house. And he's done everything he can think of to get his son to stop smoking them.

He installed cameras inside his home to try and catch his son vaping. He monitored his son's Snapchat messages, texts and emails to try to prevent vape sales.

One day he found one of his son's vapes and took him out to the backyard. He handed the boy a hammer and told him to destroy the device. There are dozens of videos on his phone now of his son, hammer in hand, breaking the vapes he was caught with.

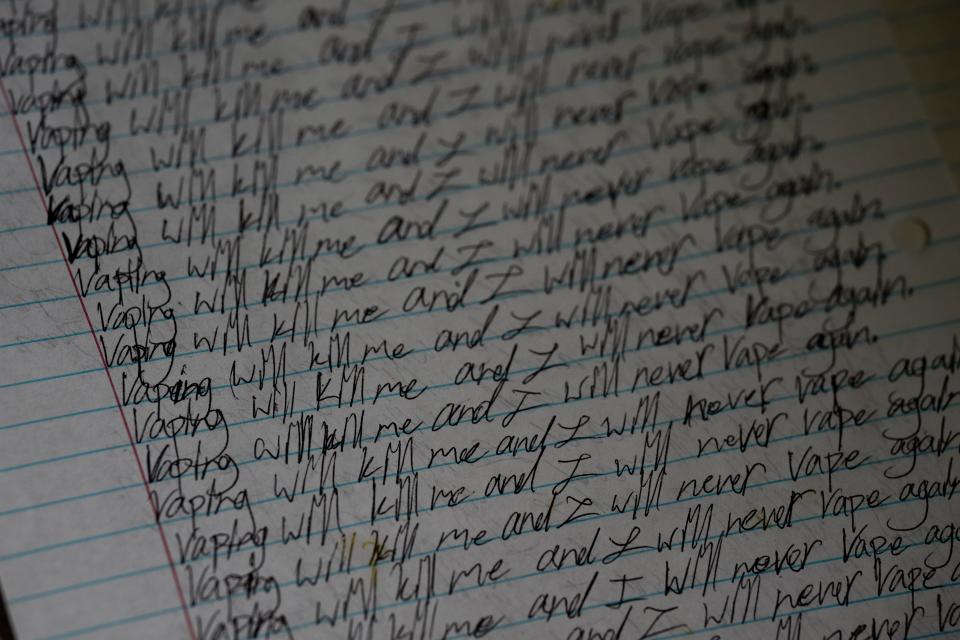

But the vapes kept turning up. Sunberg found another and called his son to the kitchen table. One hundred times over, he had his son write in black ballpoint pen: "I will not vape."

And for another vape that was found, another set of lines: "Vaping and smoking will kill me. I won't do it again."

He made his son write reports on the dangers of vaping.

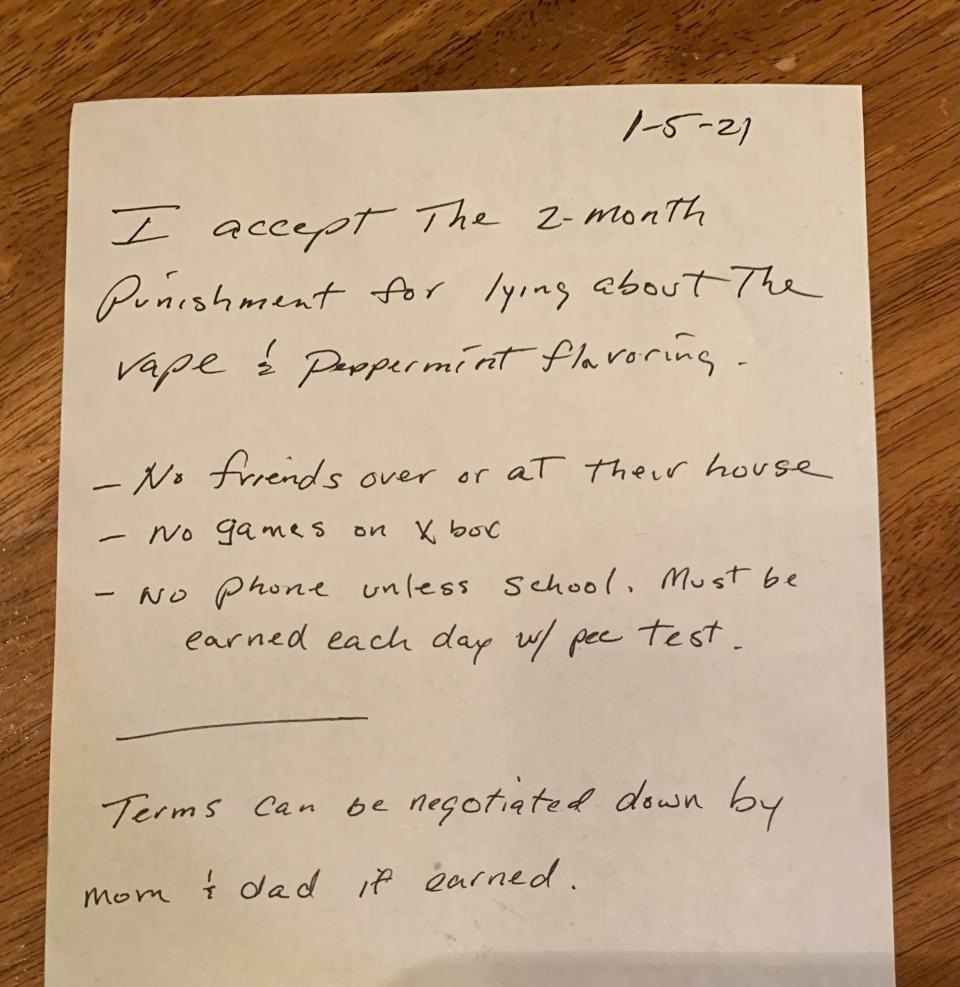

He has handwritten contracts that were signed by his son after he was caught vaping, agreeing not to have friends over, play Xbox or use his phone outside of school. The phone "must be earned each day w/ pee test," the note reads.

He even bought a metal detector wand he used on his son, every day before and after school.

"You name it," Jeff Sunberg said. "We've done it."

The couple has spent hundreds of thousands of dollars trying to save their son from his addiction. He's been through six treatment programs, the first of which cost $60,000 for a retreat to the mountains out west. Then a $15,000 post-retreat therapy program. The Sunbergs said their insurance has been generous, but their battle has still been a costly one.

And one day after returning from that first program, Jeff Sunberg said his son was vaping nicotine again.

Their son has seen therapists and professionals at Cincinnati Children's Hospital. He's gone to different schools, public and Catholic.

"None of them have worked," Hagit Sunberg said of their efforts. "That's how compelling the vape is."

The Sunbergs have spent years living in fear of what their son's addiction might do to his growing body and mind. It's enough to strain the strongest of marriages, they said. But they've been able to power through, together.

The Sunbergs still live in Anderson. Their son is taking a gap year, they said, out west. He's a recent high school graduate with a vaping addiction and little clue as to what his future holds. A future that his mother thought was so promising four years ago.

There's a framed photo in the Sunberg family's living room of their son, at his bar mitzvah. It was taken before his addiction took hold of him and the rest of the family. In the photo, he's smiling and wearing a red tie.

"He's still a good kid," Hagit Sunberg said sadly, gazing at the picture. "Hopefully he comes back to us."

Read all the stories in this special report here.

This project was underwritten, in part, by Interact for Health. Underwriters do not determine, change or restrict content.

This article originally appeared on Cincinnati Enquirer: A family spent thousands treating their son's vape addiction. Nothing worked