61-year-old Philadelphia Folk Festival is out of money and on pause, its future uncertain

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

The Philadelphia Folk Festival, which bills itself as the longest-running outdoor music festival in the country, has abandoned planning for a 2023 festival amid "dire financial straits" at the edge of bankruptcy, organizers announced this month in an open letter to members.

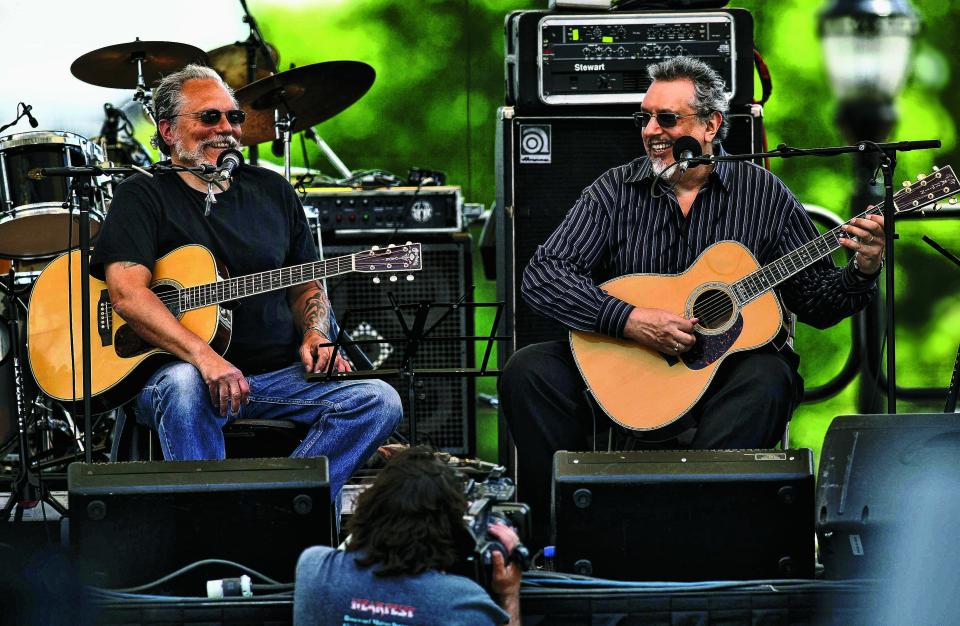

The 61-year-old festival is among the largest and most prominent of its kind, attracting as many as 25,000 fans to a four-day festival of music, camping and crafts at Montgomery County’s Old Pool Farm northwest of Philadelphia.

The festival’s history is deep, including early performances by luminaries such as Joni Mitchell, Emmylou Harris and Bonnie Raitt — not to mention Hindustani musician Ali Akhbar Khan, bluesmen Mississippi John Hurt and Taj Mahal, and hip-hop artists Arrested Development.

But now the folk festival’s future, and that of sponsoring organization the Philadelphia Folksong Society, are deeply uncertain.

The festival’s executive director, Justin Nordell, departed last week in a “mutual agreement.” Organizers say they hope to rebuild from the ground up, with renewed accountability.

“The model we use at the Philadelphia Folksong Society for generating income is broken. The model we use for the Folk Festival is broken,” said Folksong board president Miles Thompson on Wednesday in a public Zoom meeting attended by hundreds. “Philadelphia Folksong Society has used the fest as a fundraiser for over 40 years, and that no longer works.”

With often shocking transparency, Thompson and other board members laid out a financial crisis whose roots stretched back decades, in a two-hour meeting punctuated by occasional chaos and the near-constant sound of shoes dropping.

But the upshot was simple: The Folksong Society is broke.

“As of Monday, we had $757 in the bank,” Thompson said. “Not $700,000. Not $7,000. Seven hundred and fifty-seven dollars.”

The Folksong Society will vacate its current offices and music venue in Philadelphia’s Roxborough neighborhood at 6156 Ridge Ave., by May of this year, they said.

A Feb. 19 show by Scottish folk band Talisk at Philadelphia's Ardmore Music Hall will proceed as scheduled, but other Folksong events will cease until further notice.

The organization owes hundreds of thousands in back debts to the bank, the IRS, past performers, its festival venue at the Old Pool Farm in Montgomery County and music promoters, Treasurer Jim Klingler announced.

“We have $200,000 in debt, and it keeps sneaking up on us from little mouseholes,” Klingler said.

Covid, The Proud Boys and the 'Tortuga Rum Incident'

The festival's financial woes are a reckoning long in the making, Klingler said in the meeting.

During the meeting, the board, many of whom were elected only in the past two years, declined to publicly assign blame to any of their predecessors. Thompson noted that the board became aware of many back debts only recently because those finances were handled "at the executive level."

More:Sea Hear Now 2023 lineup in Asbury Park headlined by The Killers, Foo Fighters

For many years, the organization had used ticket sales for future festivals to pay off back debts from previous festivals, Klingler said, often increasing the festival's scale to do so. Ticket revenues also bankrolled organizational costs for a Folksong Society that puts on musical performances and events all over Philadelphia.

But the folk festival hasn’t been profitable in recent years, Thompson said, a situation exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic and multiple years of virtual-only festivals. Large festivals across the country, including Delaware’s Firefly Festival and the Vancouver Folk Festival, also "hit pause'' on festivals in 2023. Regionally, large music festivals have been taking root and growing in Asbury Park and, in recent years, Atlantic City, New Jersey.

Other festival woes:Firefly Music Festival canceled for 2023, promises 2024 return

“Officially, the Festival is a fundraiser for the Society, but, in most years, it barely breaks even with total costs,” Thompson wrote in a letter to members Monday. “The 60th Annual Festival, in 2022, cost approximately 1.2 million dollars to produce. Including our current expenses, we will have lost money.”

Though the organization received a more than $800,000 Shuttered Venue Operators Grant from the pandemic relief bill in 2021, Klingler said, more than half of this went immediately to back debts and payroll.

Organizers detailed a laundry list of financial ills.

After receiving “credible threats” alleging that far-right group the Proud Boys planned to disrupt the festival — threats that escalated to the Office of Homeland Security, organizers said — the festival had to spend $39,000 on a fence. About $20,000 was lost to a billing mishap organizers dubbed “the Tortuga Rum incident.” Insurance doubled during the pandemic. Other costs ballooned as well, they said.

Thompson attempted to dispel rumors that money had gone missing or astray.

“These are accusations that have been leveled for years and years and years and years,” Thompson said. “We see no evidence of that.”

But he acknowledged finances were behind after the pandemic. The organization has not completed a financial audit for any year since 2019, he said.

Philadelphia Folk Festival hopes to reboot in 2024

The Folksong Society, and the festival, now must find new funds and reimagine itself in order to survive and carry on the festival’s 61-year history, Thompson said.

“Given our current situation, the Society has two options: We could declare bankruptcy and close,” wrote Thompson in his letter to members. “Or, we could take a year to thoughtfully reimagine what PFS and PFF could be, work to reshape the Society and Fest into sustainable operations that meet our organizational mission, while we raise the funds to make that happen.”

Fundraising efforts will be made more difficult by the fact that the organization failed last year to renew its license with the Pennsylvania Bureau of Corporations and Charitable Organizations last year, Thompson said.

This means that Philadelphia Folksong Society is not legally allowed to “solicit” charitable funds in Pennsylvania, despite being a federally recognized nonprofit.

The Folksong Society can accept unsolicited checks through the mail, membership fees and moneys from outside fundraisers on sites like GoFundMe. But it cannot raise its own funds until the Pennsylvania legal situation is resolved — which will require completing a full audit of the organization’s finances through 2021.

Organizers are not giving up, they say, and hope to figure out a new format for the festival, and a new lease on life, as soon as 2024.

That’s welcome news, says longtime festival volunteer Jayne Toohey, who has co-authored a book on the festival and has volunteered as a photographer since 1985 after her first experience at the festival.

"I remember going there in one of my early festivals when Judy Collins was on stage in pouring rain," she said. "I sat in the pouring rain because I could not believe I was actually seeing her live. It just amazed me … and that has happened with so many people there."

She doesn’t want to imagine a future without the Philadelphia Folk Festival.

At the two-hour meeting, fans and volunteers bombarded the board with questions and especially with offers of help — albeit disrupted more than once by someone identified as “Billy the Furry,” who peppered the meeting with profanities.

One member asked simply why she should donate again, and how she can trust the organization.

“My money is dear to me, I don't want to just throw my money away,” she said. “Just explain and tell them how things are going to be done differently. Why I should trust you guys with my money?”

At multiple points in the meeting, board members acknowledged that the festival had been far from transparent in the past. This meeting, Thompson said, was meant to remedy all of that — to finally lay all the cards on the table, and try to save the festival and organization and keep its history alive.

Does this mean scaling back the festival? Sponsorships? Finding institutional support? They don't yet know.

“We could have easily walked away and said ‘We're done,’ ” said Thompson. “We’re here. Without a lot of sleep, and I don't have a stomach lining. And we love the festival. We love PFS. And you don't have to trust us. But we're trying our best for this thing that we love.”

Matthew Korfhage is a Philadelphia-based reporter for USA TODAY Network. Follow him on Twitter @matthewkorfhage or email mkorfhage@gannett.com

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY NETWORK: Philadelphia Folk Festival organizers cancel festival, confront debt