After 61 years in law enforcement, Warren police commissioner Bill Dwyer back in politics

He’s a legend among cops with a stunning 61 years of law enforcement in Detroit, Farmington Hills and Warren – and he still pins on a chief’s badge each day.

Bill Dwyer is also a legend in local politics. Last month, Dwyer, although a Republican, was top vote getter for City Council in blue-leaning Farmington Hills. On the same election day, 15 miles east, his last name earned fresh political clout in Warren, where Dwyer is commissioner of police.

Dwyer’s son Dave Dwyer was the top vote getter for Warren City Council. Dad beams with pride about his son. But he doesn’t hide the sad story of another son, Michael, whose charred body was found a few years ago in a burned house in Detroit. Michael Dwyer was 55 and struggled with drugs all of his life.

Losing Michael taught his dad a tragic lesson. It’s one of three lessons that he wants others to know:

∎ Drug addiction is a disease: “I’ve told that to a whole lot of parents who lost children like I did. You can’t blame yourself.” That's from a cop who dedicated much of his career to fighting gangs selling dope. His son’s death was ruled a homicide, although drugs was behind it, Dwyer says. Although he spent key years of his career raiding drug dens and arresting dealers, Dwyer now feels that the nation should spend far more on drug-treatment efforts. He applauds the bipartisan effort by Michigan Sen. Gary Peters in the U.S. Senate to expand opioid treatment for adolescent Americans as part of the SUPPORT for Patients and Communities Reauthorization Act.

∎ Don't even think of defunding cops: "It doesn't matter what your politics are. If you see what society is going through, it's ludicrous to think you can defund police and get better law enforcement. You'd get no law enforcement." Dwyer says most communities need more police, not fewer, and with better training. U.S. cities of all sizes, including small towns, especially need more investigators because "clearance rates" — the percentage of crimes that are "solved" and lead to arrests — have dropped to their lowest levels since the FBI started tracking them in the 1960s, according to a recent review by Crime Analytics newsletter.

∎ Spend more on mental health: Of all the nation's problems, "the mentally ill need the most attention. In these mass shootings, you find that 90% of these perpetrators are mentally ill. We had a situation just recently. The kid was 17 years old, and this was one o'clock in the afternoon, right on Van Dyke. He held a gun to his head and was threatening suicide. Now, that's a situation that can very easily result in death or injury to officers trying to help. We managed to end this safely, but how soon will he be back on the streets without getting adequate treatment?"

In their political campaigns before last month's elections, father and son used matching yard signs in red, white and blue.

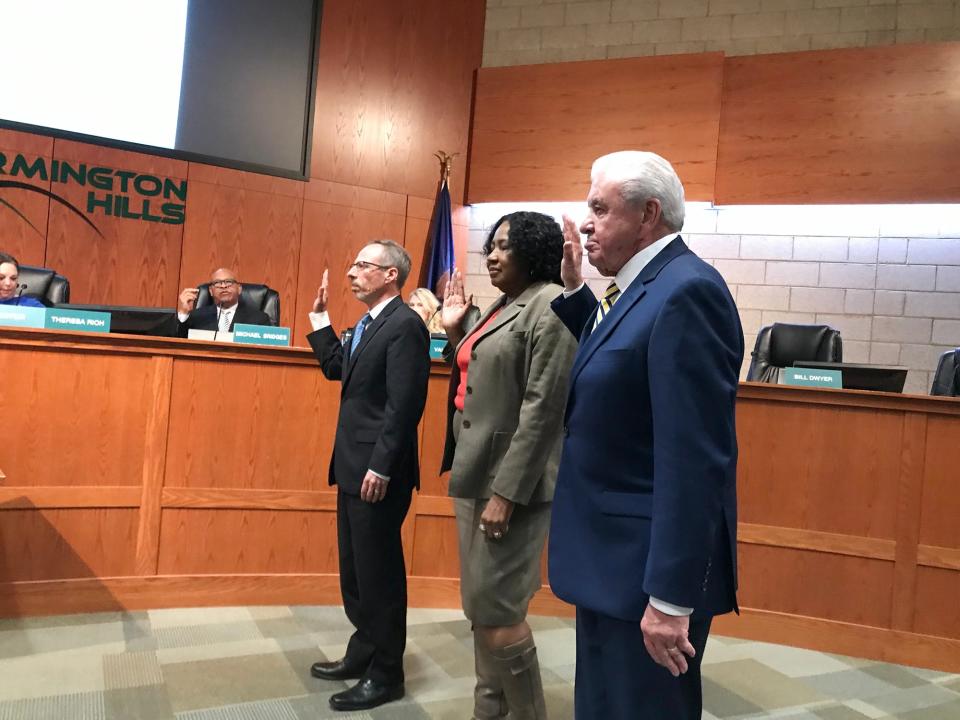

“All we changed was the first name,” Bill Dwyer says with a chuckle. Ready for his new civic duties in Farmington Hills, the senior Dwyer was sworn in last month. He’d figured a City Council seat would keep him busy when Warren’s new mayor was elected, assuming she'd broom him from his job as Warren’s top cop. No hard feelings; that’s what new mayors do, he told the Free Press months ago.

Yet, surprise awaited. Michigan’s most veteran police chief should stay on, new Warren Mayor Lori Stone decided, at least until April.

“So I told her, by April I’d really be ready to retire. But I’ll help make the transition” to a new police commissioner, Dwyer said. That means, in the coming months, he’ll still be nearby as Warren’s new City Council opens a fresh chapter. His son, Mayor Pro Tem Dave Dwyer, has joined other councilmembers in saying they've vowed not to repeat the fiascos of the last council. Its years of dissension and lawsuits with former Mayor Jim Fouts have hamstrung city government, all observers agree.

More than six decades ago, Dwyer was a recent graduate of L’Anse Creuse High School, working for his father as a carpenter. That's when he spied a newspaper ad for Detroit police recruits. After going through police academy, he started walking a beat in Detroit’s 7th Precinct and never looked back.

In 23 years on the Detroit force, Dwyer adopted a rule that he still follows: Get to work no later than 7 a.m. and often at 6 a.m. Last month, after his first council meeting in Farmington Hills, Dwyer complained with a laugh that “it ran late,” cutting short the rest for a guy in the habit of rising at 3:30 a.m. to work out at a home gym.

In the late 1970s, Dwyer began seven years in charge of Detroit’s burgeoning narcotics squad, when heroin was king of the street trade.

“We were doing 10 raids a day,” he recalls. That was when Dwyer discovered a management approach he'd use again and again: Consolidation. When he took over, every precinct had a small narcotics group, out of touch with the others. He soon changed that.

“Once I set it up, we had 28 street crews, all getting special training. And every crew had a female officer. Every crew had a Black officer. They all had to have the capacity to work undercover and buy dope,” he says.

An enemy as big as Detroit's drug enforcers? Corrupt cops. Previous Free Press reports depicted Dwyer telling his narcotics team of 180 officers that he would personally file a criminal complaint against anyone found dipping into the bundles of cash they seized.

That was the height of the nation’s war on drugs. Nancy Reagan told Americans, “Just say no.” Dwyer thought he was making a difference. Twice, he traveled to Mexico, working with federal officers, aiming to bust the notorious “Mexican connection” for heroin. Gradually, though, he realized a truism about the economics of contraband.

“You raid, you arrest the dealers, you forfeit their property. But at the end of the day, there’s always somebody else, ready to take their place,” he says.

From narcotics, after working many a 16-hour shift on narcotics, Dwyer rose in 1981 to commander rank, reporting directly to then Detroit Police Chief William Hart. In effect, he says, he ran the department, from his arrival each morning at 7 until Hart came to work “at noon or 1 o’clock." In fortuitous timing, Dwyer was gone by 1985, recruited to be chief in Farmington Hills. That put a half-hour drive between his new office and Hart, who seven years later was sentenced to 10 years in prison for embezzling $2.3 million. That cash, investigators said in court, had been seized in drug raids.

After 23 years with Detroit, Dwyer spent another 23 years in suburbia, building a reputation for hard work, fairness and equal opportunity. Bonnie Unruh of Brighton, now retired, recalls when Dwyer hired her in 1989 as a patrol cadet. Dwyer promoted her as the department's first female lieutenant and, ultimately, its first female "AC" – cop talk for assistant chief.

"He made us all want to give 110% because he did. He expects excellence and he gets excellence," Unruh said.

Dana Nessel: Key arrests made in metro Detroit mansion break-ins, retail thefts

Dwyer's reputation spread across the county line. In 2008, then Mayor Fouts tagged Dwyer to police chief of Warren, Michigan’s 3rd-largest city. Once he'd settled in, Dwyer yearned to run for the Oakland County Board of Commissioners. Fouts said he couldn’t do both jobs. So in 2010, Dwyer resigned and was elected to four 2-year terms on Oakland’s board, representing Farmington and Farmington Hills.

Known as a moderate Republican from a liberal district, Dwyer served on committees seeking gun safety and protection for victims of domestic violence. Before his third term was up, Fouts, a Democrat, called on him to come back to Warren. Dwyer began a second stint running the city's big and busy police department. Surrounded in his office by decades of law-enforcement awards and mementos, Dwyer says he’s especially proud of, yet hesitant to discuss, his grandson Branden Dwyer. Warren Police Officer Branden Dwyer is at the dawn of his career.

“I raised him,” the senior Dwyer says, because Branden’s father was disabled by drug use and his mother was unable to care for him. Sensitive to suggestions of nepotism − that his influence at the head of Warren’s department might give Branden a leg up – Dwyer says he had no say in Branden’s career: “He’s never even been in my office. Well, once, when he attended the office open house.”

More: Michigan special House elections estimated to cost upwards of $750,000

Nor is the senior Dwyer sticking his nose into the politics of Warren, where his son outpolled all candidates for City Council. Dave Dwyer started like his dad did with Detroit police, then retired after 25 years with Franklin-Bingham Farms police, and now works for the Oakland County Sheriff’s Office as a security officer in the courts. Now, like his dad, Dave Dwyer will not only enforce laws, he'll help make them.

It's a good thing to have the voice of law enforcement "in government at all levels," said Oakland County Sheriff Michael Bouchard, who, although far removed from Dave Dwyer's duties, is, in effect, his ultimate boss. Policing has become so complex, so costly, and so fraught with controversy that the first-hand experience of law enforcers can add key insights to local governance, Bouchard said.

Bill Dwyer says he’d be retired now and happy about it, and says he never would’ve sought his newest civic duty, except for one thing: his wife died. He dated Doris in high school, when he played sports and she was a cheerleader, and they married soon after graduation. She succumbed to cancer in April of last year. For a time, Dwyer says, he struggled through his grief.

“I realized the answer was: I have to keep busy," he says.

Warren’s new mayor, along with the voters of Farmington Hills, seem happy about that.

Contact Bill Laytner: blaitner@freepress.com

This article originally appeared on Detroit Free Press: Warren police commissioner Bill Dwyer back in politics