65 days without schizophrenia meds in Milwaukee County Jail leads to County paying $1M settlement

Milwaukee County Jail staff failed to give Omar Wesley schizophrenia medication 65 days over a six month period, resulting in a $1.05 million settlement finalized last month.

In 2016, Armor Correctional, the Miami-based company that previously provided medical services at the jail, had routinely failed to provide Wesley his full daily dosage of Clozapine, an antipsychotic medication used for treatment-resistant schizophrenia.

When Wesley was 21, he was diagnosed with schizophrenia, according to his mother. Court records show that he had also been diagnosed with severe schizoaffective and antisocial disorders.

He began taking Clozapine in December, 2015.

On June 24, 2016, while in the custody of the County Jail, his prescription was not refilled, the lawsuit states. Over the course of several months, Wesley's mental health "decompensated" — or deteriorated — as he was "unlawfully deprived his full daily dosage of Clozapine" while in the county's care, the lawsuit alleged.

For the last seven years, Wesley, who is now 45, has been in the care of Mendota Mental Health Institute.

"We won — we're holding people accountable," Brenda Wesley, Omar's mother, told the Journal Sentinel. "But the story continues. The journey continues."

"If he was allowed to stay on that medication and was treated right I think the outcome would have been so much better now. So, again, I'm happy about the the settlement, because we can take care of him, but I'm still sad that he's in the condition that he is in now," added Wesley, who previously served as city outreach coordinator for the National Alliance on Mental Illness and on the Milwaukee County Mental Health Board.

Wesley is represented by attorneys Craig Mastantuono and Mark Thomsen.

"It frustrates every goal of the rational sentencing model to send people to a place where they're harmed, they're made worse, because at a basic level their mental health needs aren't met," said Mastantuono, later adding: "'Take your medications' is a line that is used so often in criminal court ... but we should sure as heck assume responsibility for it when we drop the ball and don't provide medications in jail settings and we injure people and make them more injured."

Despite the requirements in its contract with Milwaukee County that would require Armor Correctional to defend and indemnify the county, Armor stated it did not have the "financial ability to fund a settlement to resolve this case or pay for any eventual judgment."

Milwaukee County and Wisconsin County Mutual Insurance Company ultimately paid the multi-million-dollar judgement amount.

“Armor left behind significant litigation, including the case brought by the Wesley family,” Milwaukee County Corporation Counsel Margaret Daun said. “(W)e intend to aggressively pursue collection from Armor.”

Armor Correctional has been at the center of litigation and investigations across the country since the company's founding in 2004.

As of June, Armor Correctional has been sued in federal court roughly 570 times, including for medical negligence, inappropriate medical and mental care, over the last two decades, according to reporting by Jacksonville-based The Tributary, federal court records and the company’s log.

In October of last year, Armor Correctional, was found criminally guilty for the 2016 death of Terrill Thomas, who died of dehydration after guards shut off water in segregation at the Milwaukee County Jail.

"Armor is just a terrible actor. Anybody that does a research nationally knows that they are just unfit to be running jails and, frankly, they need to be out of business," Thomsen told the Journal Sentinel.

He added: "If you're mentally ill and you end up in Milwaukee County Jail and you're African American, you are at great risk of harm and Milwaukee County has to do better. As a county we have to fund the jail. We have no choice but to provide the mentally ill that end up in our jail with the medical treatment they need to stay alive."

Six people have died in the jail in the last 16 months. Two of the deaths have been ruled as suicide and three natural.

The family of 21-year-old Brieon Green, who died by suicide last year, this week filed a federal civil rights lawsuit against the county, including the jail's current medical provider, Wellpath LLC.

What does the lawsuit say?

In November 2013, Wesley entered a U.S. Bank in Milwaukee's downtown, while he was experiencing auditory hallucinations. There, he "finessed the teller into surrendering a packet of money," the lawsuit says.

He was charged with robbery of a financial institution.

Wesley, however, was deemed incompetent to stand trial due to his severe mental health challenges and was admitted to the Mendota Mental Health Institute in order to try and restore competency.

After medical providers at Mendota noted that medications were failing to treat Wesley's schizophrenia, they started him on Clozapine on Dec. 1, 2015.

"Omar became Omar again," Brenda Wesley told the Journal Sentinel. "I could see the light in his eyes and he was just looking really well and we were talking and he was laughing."

On Feb. 3, 2016, Wesley was determined to be restored to full competency following the Clozapine regimen, court records note.

Wesley was transferred to the Milwaukee County House of Correction on Feb. 23.

Both Milwaukee County's jail and House of Correction — now known as the Community Reintegration Center — were and continue to be subject to a court-ordered consent decree reached in 2001 after several people in the jail sued over dangerous conditions, including poor medical care access.

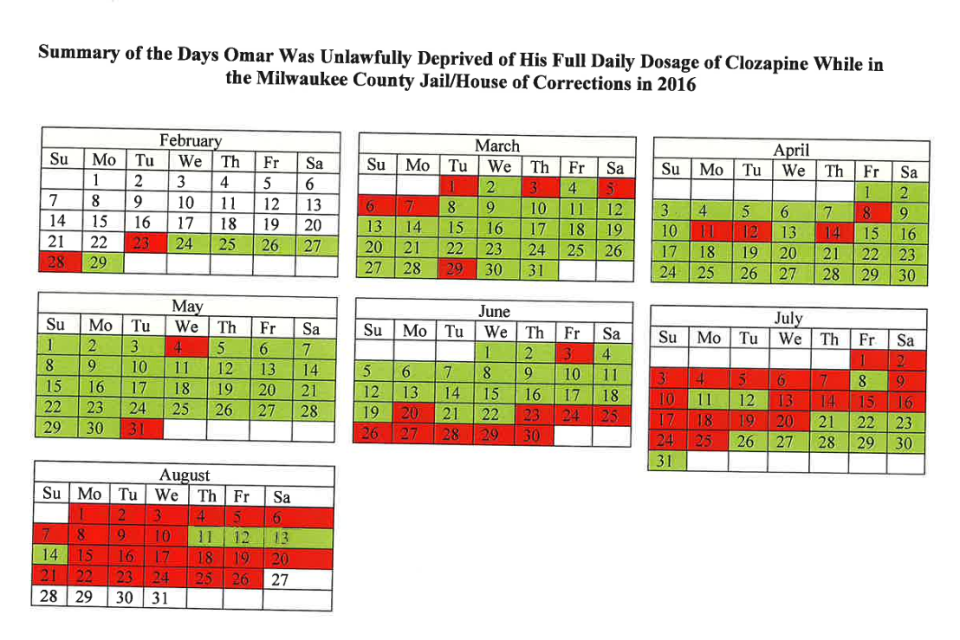

Between Feb. 23 and April 6, Wesley did not receive his fully daily dosage of Clozapine on eight days, according to his attorneys. A psychiatric nurse practitioner and Armor Correctional employee, Kim Wolf, managed his medications.

Court records show that Dr. John Pankiewicz said "I believe Mr. Wesley's psychiatric condition is stable" and "I do believe to a reasonable degree of medical certainty he could be maintained in the the community if on a set of very specific conditions."

On April 6, Wesley was transferred to a housing unit for people with severe mental health challenges in the County Jail.

Between his arrival at the jail and June 28, Wesley did not receive his full daily dosage of Clozapine on 14 days, the lawsuits says. A psychiatric nurse practitioner and independent contractor working for Armor Correctional, Deborah Mayo, managed Wesley's medications.

On June 6, Wesley appeared before Milwaukee County Circuit Court Judge William Pocan on his pending robbery charge.

Based on Pankiewicz's recommendation, the judge found Wesley not guilty by reason of mental disease or defect and ordered the Department of Health Services to prepare a conditional release plan.

While awaiting his release, Wesley's prescription for Clozapine expired on June 24 and was not renewed.

On June 28, Wesley was released from the jail to Wisconsin Community Services, Inc. and placed at community-based residential treatment facility, Hills of Love.

At the time of his release, Wesley had not received any of his medication for at least four days. He was also denied a medication voucher, which would have permitted him to get a seven-day supply of his medications from an outside pharmacy. The reasons for the denial were not clear, the lawsuit says.

On June 30, a Wisconsin Community Services, Inc. psychiatrist, Dr. Michael Ewing, noted Wesley's Clozapine had been stopped during his stay at the jail. Once Ewing confirmed that the jail had not intentionally paused his treatment for any legitimate medical reasons, he prescribed Wesley a titrated schedule of the drug, a common practice after interrupting the use of the drug and also to avoid serious side effects.

Wesley took the doses on July 8 but refused the following two days. As such his refusal violated the terms of his conditional release, meaning his community supervision was temporarily revoked and he transferred back to the jail pending his hearing.

Between July 13 and 21, he did not receive another dose of Clozapine.

Records show that after re-entering the jail, Armor Correctional staff noted Wesley missed multiple dosages of his medications. During that same period of time, Wesley was experiencing "some delusional thoughts," medical records from nurses noted.

Wesley had told medical staff "I am not sure what is real sometime," that he had "talked to this lady called Hillary Clinton" and that he had "been hearing things like these Dudes in here are going to get murdered."

On Aug. 8, a psychiatric social worker said he appeared "paranoid throughout his housing assessment."

Throughout his incarceration, Wesley irregularly took Clozapine, either due to the medication's absence or sometimes when he refused to take it.

On Aug. 9, Judge Pocan denied the state's petition to revoke Wesley's community supervision. He found that there was "no willful violation here” by Wesley, court transcripts show.

Pocan went on to conclude: “(T)he problem is the jail created this situation ... this is really inexcusable ... (the jail) in effect set Mr. Wesley up for failure."

Wesley was released from the jail the next day, but later returned after six days following an incident at a group home.

Once again, he was not given his full daily dose of Clozapine.

On Aug. 26, it was deemed that Wesley "posed a significant threat of bodily harm to himself and others," the lawsuit says. He was transferred to Mendota again.

"He has not achieved competency again since," the lawsuit says.

Since 2016, Wesley has remained at Mendota undergoing treatment.

"He's just now, seven years later, starting to come out of the fog. That's terrible," Mastantuono said.

Now with the settlement finalized, Wesley's family wants to bring him home and plan to petition for his release.

"I can set up housing myself. I can set up community services myself," said Brenda Wesley. "Omar will not have to live in total poverty and that we as a family we can wrap around him in a way that financially that we can do that."

But for his mother, she worries that people incarcerated at the jail will continue to face similar treatment.

"If they did this to Omar, what are they doing to the ones, to the people that don't have a voice? That don't have family members to advocate for them?" she asked.

Contact Vanessa Swales at 414-308-5881 or vswales@gannett.com. Follow her on Twitter @Vanessa_Swales.

This article originally appeared on Milwaukee Journal Sentinel: Lawsuit over deprived meds in Milwaukee County Jail settles for $1M